A little while back I was musing on the possibility of a People’s Card Catalog, a public access clearinghouse of information on all the world’s books to rival Google’s gated preserve. Well thanks to the Internet Archive and its offshoot the Open Content Alliance, it looks like we might now have it – ?or at least the initial building blocks. On Monday they launched a demo version of the Open Library, a grand project that aims to build a universally accessible and publicly editable directory of all books: one wiki page per book, integrating publisher and library catalogs, metadata, reader reviews, links to retailers and relevant Web content, and a menu of editions in multiple formats, both digital and print.

A little while back I was musing on the possibility of a People’s Card Catalog, a public access clearinghouse of information on all the world’s books to rival Google’s gated preserve. Well thanks to the Internet Archive and its offshoot the Open Content Alliance, it looks like we might now have it – ?or at least the initial building blocks. On Monday they launched a demo version of the Open Library, a grand project that aims to build a universally accessible and publicly editable directory of all books: one wiki page per book, integrating publisher and library catalogs, metadata, reader reviews, links to retailers and relevant Web content, and a menu of editions in multiple formats, both digital and print.

Imagine a library that collected all the world’s information about all the world’s books and made it available for everyone to view and update. We’re building that library.

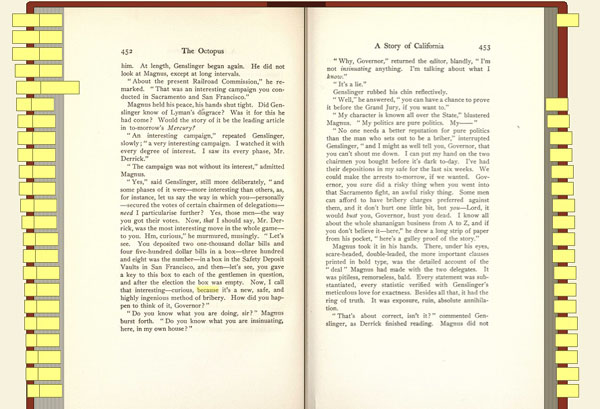

The official opening of Open Library isn’t scheduled till October, but they’ve put out the demo now to prove this is more than vaporware and to solicit feedback and rally support. If all goes well, it’s conceivable that this could become the main destination on the Web for people looking for information in and about books: a Wikipedia for libraries. On presentation of public domain texts, they already have Google beat, even with recent upgrades to the GBS system including a plain text viewing option. The Open Library provides TXT, PDF, DjVu (a high-res visual document browser), and its own custom-built Book Viewer tool, a digital page-flip interface that presents scanned public domain books in facing pages that the reader can leaf through, search and (eventually) magnify.

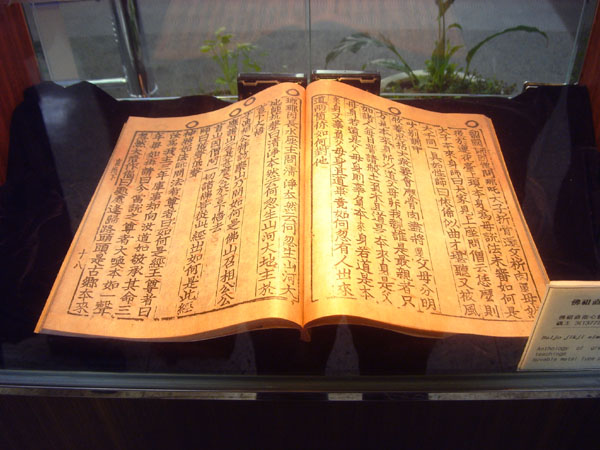

Page turning interfaces have been something of a fad recently, appearing first in the British Library’s Turning the Pages manuscript preservation program (specifically cited as inspiration for the OL Book Viewer) and later proliferating across all manner of digital magazines, comics and brochures (often through companies that you can pay to convert a PDF into a sexy virtual object complete with drag-able page corners that writhe when tickled with a mouse, and a paper-like rustling sound every time a page is turned).

This sort of reenactment of paper functionality is perhaps too literal, opting for imitation rather than innovation, but it does offer some advantages. Having a fixed frame for reading is a relief in the constantly scrolling space of the Web browser, and there are some decent navigation tools that gesture toward the ways we browse paper. To either side of the open area of a book are thin vertical lines denoting the edges of the surrounding pages. Dragging the mouse over the edges brings up scrolling page numbers in a small pop-up. Clicking on any of these takes you quickly and directly to that part of the book. Searching is also neat. Type a query and the book is suddenly interleaved with yellow tabs, with keywords highlighted on the page, like so:

But nice as this looks, functionality is sacrificed for the sake of fetishism. Sticky tabs are certainly a cool feature, but not when they’re at the expense of a straightforward list of search returns showing keywords in their sentence context. These sorts of references to the feel and functionality of the paper book are no doubt comforting to readers stepping tentatively into the digital library, but there’s something that feels disjointed about reading this way: that this is a representation of a book but not a book itself. It is a book avatar. I’ve never understood the appeal of those Second Life libraries where you must guide your virtual self to a virtual shelf, take hold of the virtual book, and then open it up on a virtual table. This strikes me as a failure of imagination, not to mention tedious. Each action is in a sense done twice: you operate a browser within which you operate a book; you move the hand that moves the hand that moves the page. Is this perhaps one too many layers of mediation to actually be able to process the book’s contents? Don’t get me wrong, the Book Viewer and everything the Open Library is doing is a laudable start (cause for celebration in fact), but in the long run we need interfaces that deal with texts as native digital objects while respecting the originals.

What may be more interesting than any of the technology previews is a longish development document outlining ambitious plans for building the Open Library user interface. This covers everything from metadata standards and wiki templates to tagging and OCR proofreading to search and browsing strategies, plus a well thought-out list of user scenarios. Clearly, they’re thinking very hard about every conceivable element of this project, including the sorts of things we frequently focus on here such as the networked aspects of texts. Acolytes of Ted Nelson will be excited to learn that a transclusion feature is in the works: a tool for embedding passages from texts into other texts that automatically track back to the source (hypertext copy-and-pasting). They’re also thinking about collaborative filtering tools like shared annotations, bookmarking and user-defined collections. All very very good, but it will take time.

Building an open source library catalog is a mammoth undertaking and will rely on millions of hours of volunteer labor, and like Wikipedia it has its fair share of built-in contradictions. Jessamyn West of librarian.net put it succinctly:

It’s a weird juxtaposition, the idea of authority and the idea of a collaborative project that anyone can work on and modify.

But the only realistic alternative may well be the library that Google is building, a proprietary database full of low-quality digital copies, a semi-accessible public domain prohibitively difficult to use or repurpose outside the Google reading room, a balkanized landscape of partner libraries and institutions left in its wake, each clutching their small slice of the digitized pie while the whole belongs only to Google, all of it geared ultimately not to readers, researchers and citizens but to consumers. Construed more broadly to include not just books but web pages, videos, images, maps etc., the Google library is a place built by us but not owned by us. We create and upload much of the content, we hand-make the links and run the search queries that program the Google brain. But all of this is captured and funneled into Google dollars and AdSense. If passive labor can build something so powerful, what might active, voluntary labor be able to achieve? Open Library aims to find out.

(Speaking of the IA, Brewster Kahle is also here and is closing the conference Wednesday afternoon. He brought with him a test model of the hundred dollar laptop, which he showed off at dinner (pic to the right) in tablet mode sporting an e-book from the Open Content Alliance’s children’s literature collection (a scanned copy of The Owl and the Pussycat)).

(Speaking of the IA, Brewster Kahle is also here and is closing the conference Wednesday afternoon. He brought with him a test model of the hundred dollar laptop, which he showed off at dinner (pic to the right) in tablet mode sporting an e-book from the Open Content Alliance’s children’s literature collection (a scanned copy of The Owl and the Pussycat)).