This is a request for comments. We’re in the very early stages of devising, in partnership with Peter Brantley and the Digital Library Federation, what could become a major initiative around the question of mass digitization. It’s called “The Really Modern Library.”

Over the course of this month, starting Thursday in Los Angeles, we’re holding a series of three invited brainstorm sessions (the second in London, the third in New York) with an eclectic assortment of creative thinkers from the arts, publishing, media, design, academic and library worlds to better wrap our minds around the problems and sketch out some concrete ideas for intervention. Below I’ve reproduced some text we’ve been sending around describing the basic idea for the project, followed by a rough agenda for our first meeting. The latter consists mainly of questions, most of which, if not all, could probably use some fine tuning. Please feel encouraged to post responses, both to the individual questions and to the project concept as a whole. Also please add your own queries, observations or advice.

The Really Modern Library (basically)

The goal of this project is to shed light on the big questions about future accessibility and usability of analog culture in a digital, networked world.

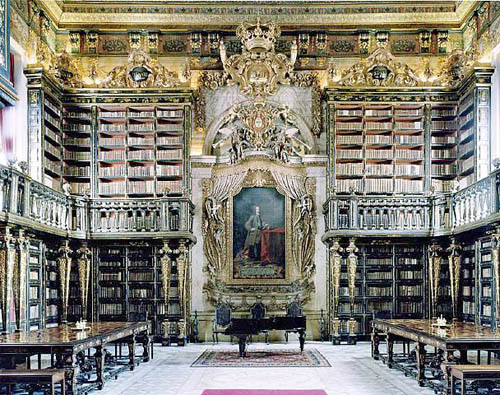

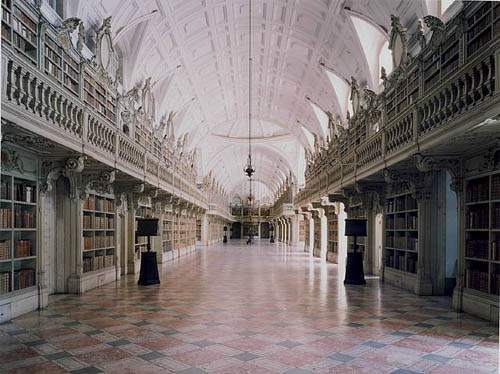

We are in the midst of a historic “upload,” a frenetic rush to transfer the vast wealth of analog culture to the digital domain. Mass digitization of print, images, sound and film/video proceeds apace through the efforts of actors public and private, and yet it is still barely understood how the media of the past ought to be preserved, presented and interconnected for the future. How might we bring the records of our culture with us in ways that respect the originals but also take advantage of new media technologies to enhance and reinvent them?

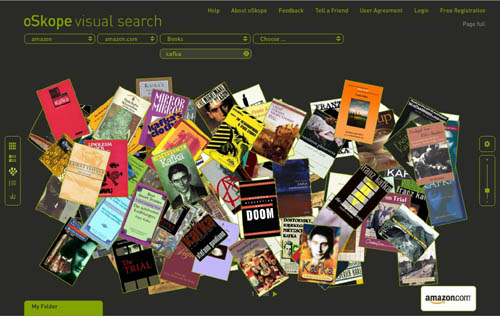

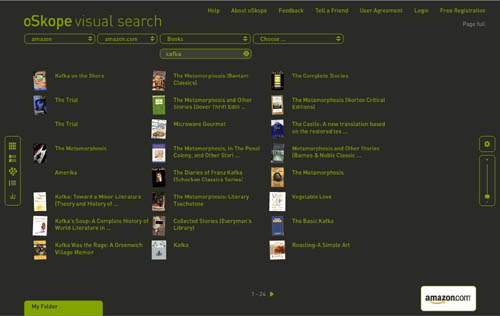

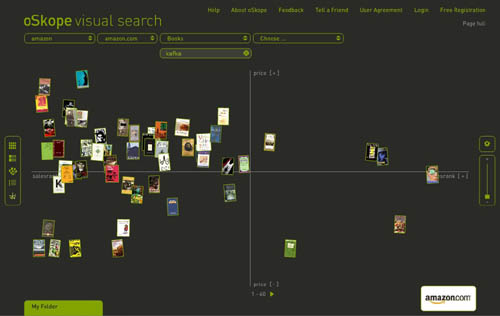

Our aim with the Really Modern Library project is not to build a physical or even a virtual library, but to stimulate new thinking about mass digitization and, through the generation of inspiring new designs, interfaces and conceptual models, to spur innovation in publishing, media, libraries, academia and the arts.

The meeting in October will have two purposes. The first is to deepen and extend our understanding of the goals of the project and how they might best be achieved. The second is to begin outlining plans for a major international design competition calling for proposals, sketches, and prototypes for a hypothetical “really modern library.” This competition will seek entries ranging from the highly particular (for e.g., designs for digital editions of analog works, or new tools and interfaces for handling pre-digital media) to the broadly conceptual (ideas of how to visualize, browse and make use of large networked collections).

This project is animated by a strong belief that it is the network, more than the simple conversion of atoms to bits, that constitutes the real paradigm shift inherent in digital communication. Therefore, a central question of the Really Modern Library project and competition will be: how does the digital network change our relationship with analog objects? What does it mean for readers/researchers/learners to be in direct communication in and around pieces of media? What should be the *social* architecture of a really modern library?

The call for entries will go out to as broad a community as possible, including designers, artists, programmers, hackers, librarians, archivists, activists, educators, students and creative amateurs. Our present intent is to raise a large sum of money to administer the competition and to have a pool for prizes that is sufficiently large and meaningful that it can compel significant attention from the sort of minds we want working on these problems.

Meeting Agenda

Although we have tended to divide the Really Modern Library Project into two stages – the first addressing the question of how we might best take analog culture with us into the digitally networked future and the second, how the digitally networked library of the future might best be conceived and organized – these questions are joined at the hip and not easily or productively isolated from each other.

Realistically, any substantive answer to the question of how to re-present artifacts of analog culture in the digital network immediately raises issues ranging from new forms of browsing (in a social network) to new forms of reading (in a social network) which have everything to do with the broader infrastructure of the library itself.

We’re going to divide the day roughly in half, spending the morning confronting the broader conceptual issues and the afternoon discussing what kind of concrete intervention might make sense.

Questions to think about in preparation for the morning discussion:

* if it’s assumed that form and content are inextricably linked, what happens when we take a book and render it on a dynamic electronic screen rather than bound paper? same question for movies which move from the large theatrical presentation to the intimacy of the personal screen. interestingly the “old” analog forms aren’t as singular as they might seem. books are read silently alone or out loud in public; music is played live and listened to on recordings. a recording of a Beethoven symphony on ten 78rpm discs presents quite a different experience than listening to it on an iPod with random access. from this perspective how do we define the essence of a work which needs to be respected and protected in the act of re-presentation?

* twenty years ago we added audio commentary tracks to movies and textual commentary to music. given the spectacular advances in computing power, what are the most compelling enhancements we might imagine. (in preparation for this, you may find it useful to look at a series of exchanges that took place on the if:book blog regarding an “ideal presentation of Ulysses” (here and here).

* what are the affordances of locating a work in the shared social space of a digital network. what is the value of putting readers, viewers, and listeners of specific works in touch with each other. what can we imagine about the range of interactions that are possible and worthwhile. be expansive here, extrapolating as far out as possible from current technical possibilities.

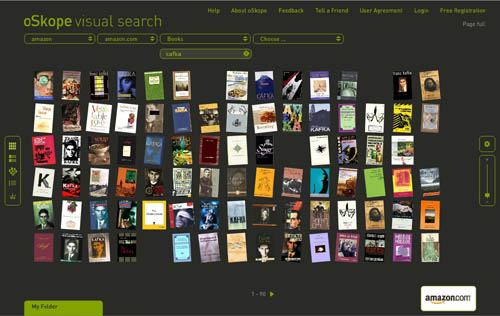

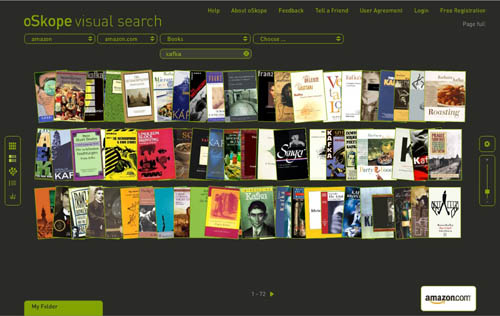

* it seems to us that visualization tools will be crucial in the digital future both for opening up analog works in new ways and for browsing and making sense of massive media archives. if everything is theoretically connected to everything else, how do we make those connections visible in a way that illuminates rather than overwhelms? and how do we visualize the additional and sometimes transformative connections that people make individually and communally around works? how do we visualize the conversation that emerges?

* in the digital environment, all media break down into ones and zeros. all media can be experienced on a single device: a computer. what are the implications of this? what are the challenges in keeping historical differences between media forms in perspective as digitization melts everything together?

* what happens when computers can start reading all the records of human civilization? in other words, when all analog media are digitized, what kind of advanced data crunching can we do and what sorts of things might it reveal?

* most analog works were intended to be experienced with all of one’s attention, but the way we read/watch/listen/look is changing. even when engaging with non-networked media -? a paper book, a print newspaper, a compact disc, a DVD, a collection of photos -? we increasingly find ourselves Googling alongside. Al Pacino paces outside the bank in ‘dog day afternoon’ firing up the crowded street with “Attica! Attica!” I flip to Wikipedia and do quick read on the Attica prison riots. reading “song of myself” in “leaves of grass,” i find my way to the online Whitman archive, which allows me to compare every iteration of Whitman’s evolutionary work. or reading “ulysses” i open up Google Earth and retrace Bloom’s steps by satellite. while leafing through a book of caravaggio’s paintings, a quick google video search leads me to a related episode in simon schama’s “power of art” documentary series and a series of online essays. as radiohead’s new album plays, i browse fan sites and blogs for backstory, b-sides and touring info. the immediacy and proximity of such supplementary resources changes our relationship to the primary ones. the ratio of text to context is shifting. how should this influence the structure and design of future digital editions?

Afternoon questions:

* if we do decide to mount a competition (we’re still far from decided on whether this is the right approach), how exactly should it work? first off, what are we judging? what are we hoping to reward? what is the structure of this contest? what are the motivators? a big concern is that the top-down model -? panel of prestigious judges, serious prize money etc. -? feels very old-fashioned and ignores the way in which much of the recent innovation in digital media has taken place: an emergent, grassroots ferment… open source culture, web2.0, or what have you. how can we combine the heft and focused energy of the former with the looseness and dynamism of the latter? is there a way to achieve some sort of top-down orchestration of emergent creativity? is “competition” maybe the wrong word? and how do we create a meaningful public forum that can raise consciousness of these issues more generally? an accompanying website? some other kind of publication? public events? a conference?

* where are the leverage points are for an intervention in this area? what are the key consituencies, national vs. international?

* for reasons both practical and political, we’ve considered restricting this contest to the public domain. practical in that the public domain provides an unencumbered test bed of creative content for contributors to work with (no copyright hassles). political in that we wish to draw attention to the threat posed to the public domain by commercially driven digitization projects ( i.e. the recent spate of deals between Google and libraries, the National Archives’ deal with Footnote.com and Amazon, the Smithsonian with Showtime etc.). emphasizing the public domain could also exert pressure on the media industries, who to date have been more concerned with preserving old architectures of revenue than with adapting creatively to the digital age. making the public domain more attractive, more dynamic and more *usable* than the private domain could serve as a wake-up call to the big media incumbents, and more importantly, to contemporary artists and scholars whose work is being shackled by overly restrictive formats and antiquated business models. we’d also consider workable areas of the private domain such as the Creative Commons -? works that are progressively licensed so as to allow creative reuse. we’re not necessarily wedded to this idea. what do you think?

Monkeybook is an occasional series of new media evenings hosted by the Institute for the Future of the Book at Monkey Town, Brooklyn’s premier video salon and A/V sandbox.

Monkeybook is an occasional series of new media evenings hosted by the Institute for the Future of the Book at Monkey Town, Brooklyn’s premier video salon and A/V sandbox.