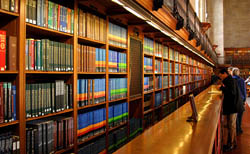

Here’s a wonderful thing I stumbled across the other day: GAM3R 7H30RY has its very own listing in North Carolina State University’s online library catalog.

The catalog is worth browsing in general. Since January, it’s been powered by Endeca, a fantastic library search tool that, among many other things, preserves some of the serendipity of physical browsing by letting you search the shelves around your title.

(Thanks, Monica McCormick!)

Category Archives: libraries

what’s important to save

Rick Prelinger and Megan Shaw visited for lunch earlier in the week and gave us a preview of the very interesting presentation they made later that day about the SF-based Prelinger Library . Beginning in the 70s Rick started collecting film and video that no one else seemed to want — industrials (e.g. GM’s worldfair and auto show films), educational films (think “how to be popular”, “how to be a good citizen” and how to make the perfect jelly), and filmed advertisements to be shown in movie theaters and early TV. Rick’s contention, as the first serious media archaeologist, was that these films that no one intended to be saved or seen again — ephemeral films — often provided much more insight about howsociety has evolved in the twentieth century than the big budget hollywood films which tend to be more self-conscious and indirect.

Below are a few clips from some of my favorites. the clip from “A Date With Your Family” contains one of the scariest moments i’ve ever encountered in film, when at the end of the clip, the narrator remarks as “father” returns from his day at the office . . . . that “these boys greet their dad AS THOUGH they are genuinely glad to see him, AS THOUGH they had really missed being away from him during the day . . . ” In the second clip, “A Young Man’s Fancy,” the daughter in a pensive mood says “I was just thinking” and the mother says incredulously, “thinking?” as if that’s the most outlandish thing she can imagine her daughter doing.

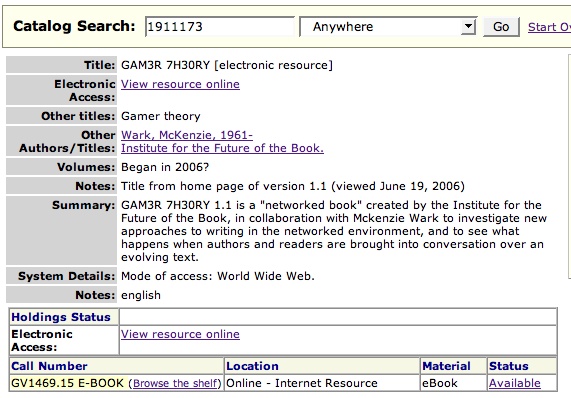

A few years ago, the Library of Congress, recognizing the inestimable value of Rick’s collection, bought the whole kit and caboodle. Since then, Rick and his partner, Megan Shaw have turned their attention to print, building a library of unusual books, periodicals and print ephemera; e.g. an invaluable collection of ESSO’s state maps from the fities that favors serendipitous browsing and remix. (the cover of the ESSO map below depicts a young boy being introduced by his dad to the wonders of nuclear fusion).

The following is from the description on the library’s website:

Though libraries live on (and are among the least-corrupted democratic institutions), the freedom to browse serendipitously is becoming rarer. Now that many research libraries are economizing on space and converting print collections to microfilm and digital formats, it’s becoming harder to wander and let the shelves themselves suggest new directions and ideas. Key academic and research libraries are often closed to unaffiliated users, and many keep the bulk of their collections in closed stacks, inhibiting the rewarding pleasures of browsing. Despite its virtues, query-based online cataloging often prevents unanticipated yet productive results from turning up on the user’s screen. And finally, much of the material in our collection is difficult to find in most libraries readily accessible to the general public.

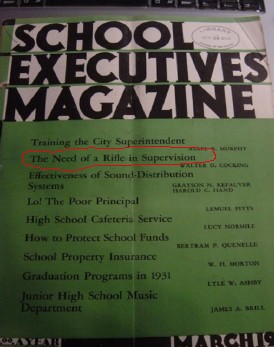

While listening to Rick and Megan’s talk i had a minor AHA moment. a lot of our skepticism and concern about Google centers on the inherent dangers of a private company being entrusted with the care and feeding of our increasingly digitize culture. When Rick and Megan showed the cover of School Executives, a journal from the 40s, which featured an article on the value of teachers toting guns to enforce classroom discipline, i realized that Google’s digitization efforts focus entirely on codex books (maybe to be extended to periodicals that libraries have bothered to store). but the invaluable materials that might be called “print-based” ephemera — pamphlets, marketing materials, off-beat journals, zines etc. — will be absent in the future. The sad thing about this, as we know from Rick’s ephemeral film collection, is that often these pieces that were never meant to survive tell us more about how our culture evolved and how we’ve ended up where we are, than many self-conscious efforts conceived with permanence in mind.

library wisdom

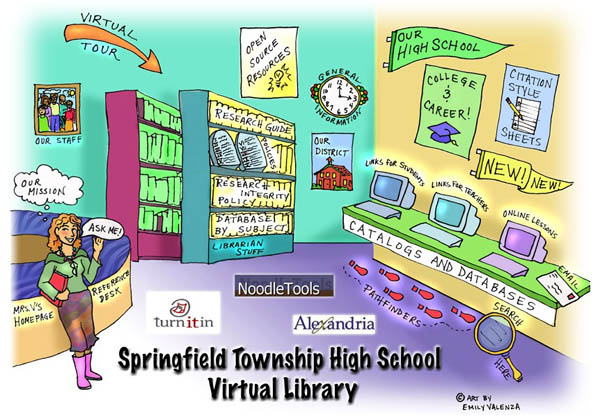

Bob and I have been impressed with what we’ve been reading on a series of sites maintained by Joyce Valenza, a teacher-Librarian at the Springfield Township High School Library in Erdenheim, Pennsylvania. Of particular interest is a chart she’s put together entitled “30 Years of Information and Educational Change: How should our practice respond?” which records the dramatic technological shifts that have taken place since she began studying library science nearly three decades ago, and how her thinking has evolved:

I graduated with an MLS in 1977 and had to return and redo most of the credits in 1987/1988 to get education credentials. While I learned programming the first time around and personal computer applications the second time around, the rate of change has dramatically altered the landscape.

I see an urgent need for librarians to retool. We cannot expect to assume a leadership role in information technology and instruction, we cannot claim any credibility with students, faculty, or administrators if we do not recognize and thoughtfully exploit the paradigm shift of the past two years. Retooling is essential for the survival of the profession.

The role of the librarian has traditionally to guide the user into a dense grove of knowledge, instructing them how best to penetrate, navigate and reference a relatively stable corpus. But with the explosion of personal computers and networks comes the explosion of the library. The librarian becomes a strategic advisor at the gateway to a much larger and continually shifting array of resources and tools that extends well beyond the physical boundaries of the library. The user no longer needs to be guided inward, but guided outward, and in multiple directions. The librarian in an academic or school setting must help students and scholars to match up the right materials with the right modes of communication, while also fostering a critical and ethical outlook in a world awash in information. The librarian is more crucial than ever.

The physical space of the library is still vital too, Valenza argues, and nowhere is this better conveyed than in this charming “virtual library” page she has constructed for the library’s home page (that’s her standing by the reference desk):

It seems almost too obvious to use the physical library as an interface, but I was immediately struck by how intuitive and useful this page is, and how, so simply and with such spirit, it creates an almost visceral link between the physical library and its online dimensions.

(Also check out Valenza’s blog, NeverEnding Search.)

google offers public domain downloads

Google announced today that it has made free downloadable PDFs available for many of the public domain books in its database. This is a good thing, but there are several problems with how they’ve done it. The main thing is that these PDFs aren’t actually text, they’re simply strings of images from the scanned library books. As a result, you can’t select and copy text, nor can you search the document, unless, of course, you do it online in Google. So while public access to these books is a big win, Google still has us locked into the system if we want to take advantage of these books as digital texts.

A small note about the public domain. Editions are key. A large number of books scanned so far by Google have contents in the public domain, but are in editions published after the cut-off (I think we’re talking 1923 for most books). Take this 2003 Signet Classic edition of the Darwin’s The Origin of Species. Clearly, a public domain text, but the book is in “limited preview” mode on Google because the edition contains an introduction written in 1958. Copyright experts out there: is it just this that makes the book off limits? Or is the whole edition somehow copyrighted?

Other responses from Teleread and Planet PDF, which has some detailed suggestions on how Google could improve this service.

showtiming our libraries

Google’s contract with the University of California to digitize library holdings was made public today after pressure from The Chronicle of Higher Education and others. The Chronicle discusses some of the key points in the agreement, including the astonishing fact that Google plans to scan as many as 3,000 titles per day, and its commitment, at UC’s insistence, to always make public domain texts freely and wholly available through its web services.

Google’s contract with the University of California to digitize library holdings was made public today after pressure from The Chronicle of Higher Education and others. The Chronicle discusses some of the key points in the agreement, including the astonishing fact that Google plans to scan as many as 3,000 titles per day, and its commitment, at UC’s insistence, to always make public domain texts freely and wholly available through its web services.

But there are darker revelations as well, and Jeff Ubois, a TV-film archivist and research associate at Berkeley’s School of Information Management and Systems, hones in on some of these on his blog. Around the time that the Google-UC deal was first announced, Ubois compared it to Showtime’s now-infamous compact with the Smithsonian, which caused a ripple of outrage this past April. That deal, the details of which are secret, basically gives Showtime exclusive access to the Smithsonian’s film and video archive for the next 30 years.

The parallels to the Google library project are many. Four of the six partner libraries, like the Smithsonian, are publicly funded institutions. And all the agreements, with the exception of U. Michigan, and now UC, are non-disclosure. Brewster Kahle, leader of the rival Open Content Alliance, put the problem clearly and succinctly in a quote in today’s Chronicle piece:

We want a public library system in the digital age, but what we are getting is a private library system controlled by a single corporation.

He was referring specifically to sections of this latest contract that greatly limit UC’s use of Google copies and would bar them from pooling them in cooperative library systems. I vocalized these concerns rather forcefully in my post yesterday, and may have gotten a couple of details wrong, or slightly overstated the point about librarians ceding their authority to Google’s algorithms (some of the pushback in comments and on other blogs has been very helpful). But the basic points still stand, and the revelations today from the UC contract serve to underscore that. This ought to galvanize librarians, educators and the general public to ask tougher questions about what Google and its partners are doing. Of course, all these points could be rendered moot by one or two bad decisions from the courts.

librarians, hold google accountable

I’m quite disappointed by this op-ed on Google’s library intiative in Tuesday’s Washington Post. It comes from Richard Ekman, president of the Council of Independent Colleges, which represents 570 independent colleges and universities in the US (and a few abroad). Generally, these are mid-tier schools — not the elite powerhouses Google has partnered with in its digitization efforts — and so, being neither a publisher, nor a direct representative of one of the cooperating libraries, I expected Ekman might take a more measured approach to this issue, which usually elicits either ecstatic support or vociferous opposition. Alas, no.

To the opposition, namely, the publishing industry, Ekman offers the usual rationale: Google, by digitizing the collections of six of the english-speaking world’s leading libraries (and, presumably, more are to follow) is doing humanity a great service, while still fundamentally respecting copyrights — so let’s not stand in its way. With Google, however, and with his own peers in education, he is less exacting.

The nation’s colleges and universities should support Google’s controversial project to digitize great libraries and offer books online. It has the potential to do a lot of good for higher education in this country.

Now, I’ve poked around a bit and located the agreement between Google and the U. of Michigan (freely available online), which affords a keyhole view onto these grand bargains. Basically, Google makes scans of U. of M.’s books, giving them images and optical character recognition files (the texts gleaned from the scans) for use within their library system, keeping the same for its own web services. In other words, both sides get a copy, both sides win.

If you’re not Michigan or Google, though, the benefits are less clear. Sure, it’s great that books now come up in web searches, and there’s plenty of good browsing to be done (and the public domain texts, available in full, are a real asset). But we’re in trouble if this is the research tool that is to replace, by force of market and by force of users’ habits, online library catalogues. That’s because no sane librarian would outsource their profession to an unaccountable private entity that refuses to disclose the workings of its system — in other words, how does Google’s book algorithm work, how are the search results ranked? And yet so many librarians are behind this plan. Am I to conclude that they’ve all gone insane? Or are they just so anxious about the pace of technological change, driven to distraction by fears of obsolescence and diminishing reach, that they are willing to throw their support uncritically behind the company, who, like a frontier huckster, promises miracle cures and grand visions of universal knowledge?

We may be resigned to the steady takeover of college bookstores around the country by Barnes and Noble, but how do we feel about a Barnes and Noble-like entity taking over our library systems? Because that is essentially what is happening. We ought to consider the Google library pact as the latest chapter in a recent history of consolidation and conglomeratization in publishing, which, for the past few decades (probably longer, I need to look into this further) has been creeping insidiously into our institutions of higher learning. When Google struck its latest deal with the University of California, and its more than 100 libraries, it made headlines in the technology and education sections of newspapers, but it might just as well have appeared in the business pages under mergers and acquisitions.

So what? you say. Why shouldn’t leaders in technology and education seek each other out and forge mutually beneficial relationships, relationships that might yield substantial benefits for large numbers of people? Okay. But we have to consider how these deals among titans will remap the information landscape for the rest of us. There is a prevailing attitude today, evidenced by the simplistic public debate around this issue, that one must accept technological advances on the terms set by those making the advances. To question Google (and its collaborators) means being labeled reactionary, a dinosaur, or technophobic. But this is silly. Criticizing Google does not mean I am against digital libraries. To the contrary, I am wholeheartedly in favor of digital libraries, just the right kind of digital libraries.

What good is Google’s project if it does little more than enhance the world’s elite libraries and give Google the competitive edge in the search wars (not to mention positioning them in future ebook and print-on-demand markets)? Not just our little institute, but larger interest groups like the CIC ought to be voices of caution and moderation, celebrating these technological breakthroughs, but at the same time demanding that Google Book Search be more than a cushy quid pro quo between the powerful, with trickle-down benefits that are dubious at best. They should demand commitments from the big libraries to spread the digital wealth through cooperative web services, and from Google to abide by certain standards in its own web services, so that smaller librarians in smaller ponds (and the users they represent) can trust these fantastic and seductive new resources. But Ekman, who represents 570 of these smaller ponds, doesn’t raise any of these questions. He just joins the chorus of approval.

What’s frustrating is that the partner libraries themselves are in the best position to make demands. After all, they have the books that Google wants, so they could easily set more stringent guidelines for how these resources are to be redeployed. But why should they be so magnanimous? Why should they demand that the wealth be shared among all institutions? If every student can access Harvard’s books with the click of a mouse, than what makes Harvard Harvard? Or Stanford Stanford?

Enlightened self-interest goes only so far. And so I repeat, that’s why people like Ekman, and organizations like the CIC, should be applying pressure to the Harvards and Stanfords, as should organizations like the Digital Library Federation, which the Michigan-Google contract mentions as a possible beneficiary, through “cooperative web services,” of the Google scanning. As stipulated in that section (4.4.2), however, any sharing with the DLF is left to Michigan’s “sole discretion.” Here, then, is a pressure point! And I’m sure there are others that a more skilled reader of such documents could locate. But a quick Google search (acceptable levels of irony) of “Digital Library Federation AND Google” yields nothing that even hints at any negotiations to this effect. Please, someone set me straight, I would love to be proved wrong.

Google, a private company, is in the process of annexing a major province of public knowledge, and we are allowing it to do so unchallenged. To call the publishers’ legal challenge a real challenge, is to misidentify what really is at stake. Years from now, when Google, or something like it, exerts unimaginable influence over every aspect of our informated lives, we might look back on these skirmishes as the fatal turning point. So that’s why I turn to the librarians. Raise a ruckus.

UPDATE (8/25): The University of California-Google contract has just been released. See my post on this.

microsoft enlists big libraries but won’t push copyright envelope

In a significant challenge to Google, Microsoft has struck deals with the University of California (all ten campuses) and the University of Toronto to incorporate their vast library collections – nearly 50 million books in all – into Windows Live Book Search. However, a majority of these books won’t be eligible for inclusion in MS’s database. As a member of the decidedly cautious Open Content Alliance, Windows Live will restrict its scanning operations to books either clearly in the public domain or expressly submitted by publishers, leaving out the huge percentage of volumes in those libraries (if it’s at all like the Google five, we’re talking 75%) that are in copyright but out of print. Despite my deep reservations about Google’s ascendancy, they deserve credit for taking a much bolder stand on fair use, working to repair a major market failure by rescuing works from copyright purgatory. Although uploading libraries into a commercial search enclosure is an ambiguous sort of rescue.

a2k wrap-up

—Jack Balkin, from opening plenary

I’m back from the A2K conference. The conference focused on intellectual property regimes and international development issues associated with access to medical, health, science, and technology information. Many of the plenary panels dealt specifically with the international IP regime, currently enshrined in several treaties: WIPO, TRIPS, Berne Convention, (and a few more. More from Ray on those). But many others, instead of relying on the language in the treaties, focused developing new language for advocacy, based on human rights: access to knowledge as an issue of justice and human dignity, not just an issue of intellectual property or infrastructure. The Institute is an advocate of open access, transparency, and sharing, so we have the same mentality as most of the participants, even if we choose to assail the status quo from a grassroots level, rather than the high halls of policy. Most of the discussions and presentations about international IP law were generally outside of the scope of our work, but many of the smaller panels dealt with issues that, for me, illuminated our work in a new light.

In the Peer Production and Education panel, two organizations caught my attention: Taking IT Global and the International Institute for Communication and Development (IICD). Taking IT Global is an international youth community site, notable for its success with cross-cultural projects, and for the fact that it has been translated into seven languages—by volunteers. The IICD trains trainers in Africa. These trainers then go on to help others learn the technological skills necessary to obtain basic information and to empower them to participate in creating information to share.

—Ronaldo Lemos

The ideology of empowerment ran thick in the plenary panels. Ronaldo Lemos, in the Political Economy of A2K, dropped a few figures that showed just how powerful communities outside the scope and target of traditional development can be. He talked about communities at the edge, peripheries, that are using technology to transform cultural production. He dropped a few figures that staggered the crowd: last year Hollywood produced 611 films. But Nigeria, a country with only ONE movie theater (in the whole nation!) released 1200 films. To answer the question of how? No copyright law, inexpensive technology, and low budgets (to say the least). He also mentioned the music industry in Brazil, where cultural production through mainstream corporations is about 52 CDs of Brazilian artists in all genres. In the favelas they are releasing about 400 albums a year. It’s cheaper, and it’s what they want to hear (mostly baile funk).

We also heard the empowerment theme and A2K as “a demand of justice” from Jack Balkin, Yochai Benkler, Nagla Rizk, from Egypt, and from John Howkins, who framed the A2K movement as primarily an issue of freedom to be creative.

The panel on Wireless ICT’s (and the accompanying wiki page) made it abundantly obvious that access isn’t only abut IP law and treaties: it’s also about physical access, computing capacity, and training. This was a continuation of the Network Neutrality panel, and carried through later with a rousing presentation by Onno W. Purbo, on how he has been teaching people to “steal” the last mile infrastructure from the frequencies in the air.

Finally, I went to the Role of Libraries in A2K panel. The panelists spoke on several different topics which were familiar territory for us at the Institute: the role of commercialized information intermediaries (Google, Amazon), fair use exemptions for digital media (including video and audio), the need for Open Access (we only have 15% of peer-reviewed journals available openly), ways to advocate for increased access, better archiving, and enabling A2K in developing countries through libraries.

—The Adelphi Charter

The name of the movement, Access to Knowledge, was chosen because, at the highest levels of international politics, it was the one phrase that everyone supported and no one opposed. It is an undeniable umbrella movement, under which different channels of activism, across multiple disciplines, can marshal their strength. The panelists raised important issues about development and capacity, but with a focus on human rights, justice, and dignity through participation. It was challenging, but reinvigorating, to hear some of our own rhetoric at the Institute repeated in the context of this much larger movement. We at the Institute are concerned with the uses of technology whether that is in the US or internationally, and we’ll continue, in our own way, to embrace development with the goal of creating a future where technology serves to enable human dignity, creativity, and participation.

can there be a compromise on copyright?

The following is a response to a comment made by Karen Schneider on my Monday post on libraries and DRM. I originally wrote this as just another comment, but as you can see, it’s kind of taken on a life of its own. At any rate, it seemed to make sense to give it its own space, if for no other reason than that it temporarily sidelined something else I was writing for today. It also has a few good quotes that might be of interest. So, Karen said:

I would turn back to you and ask how authors and publishers can continue to be compensated for their work if a library that would buy ten copies of a book could now buy one. I’m not being reactive, just asking the question–as a librarian, and as a writer.

This is a big question, perhaps the biggest since economics will define the parameters of much that is being discussed here. How do we move from an old economy of knowledge based on the trafficking of intellectual commodities to a new economy where value is placed not on individual copies of things that, as a result of new technologies are effortlessly copiable, but rather on access to networks of content and the quality of those networks? The question is brought into particularly stark relief when we talk about libraries, which (correct me if I’m wrong) have always been more concerned with the pure pursuit and dissemination of knowledge than with the economics of publishing.

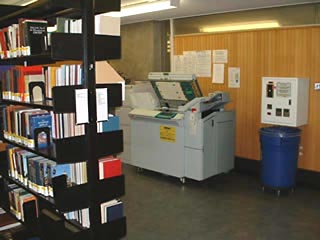

Consider, as an example, the photocopier — in many ways a predecessor of the world wide web in that it is designed to deconstruct and multiply documents. Photocopiers have been unbundling books in libraries long before there was any such thing as Google Book Search, helping users break through the commodified shell to get at the fruit within.

Consider, as an example, the photocopier — in many ways a predecessor of the world wide web in that it is designed to deconstruct and multiply documents. Photocopiers have been unbundling books in libraries long before there was any such thing as Google Book Search, helping users break through the commodified shell to get at the fruit within.

I know there are some countries in Europe that funnel a share of proceeds from library photocopiers back to the publishers, and this seems to be a reasonably fair compromise. But the role of the photocopier in most libraries of the world is more subversive, gently repudiating, with its low hum, sweeping light, and clackety trays, the idea that there can really be such a thing as intellectual property.

That being said, few would dispute the right of an author to benefit economically from his or her intellectual labor; we just have to ask whether the current system is really serving in the authors’ interest, let alone the public interest. New technologies have released intellectual works from the restraints of tangible property, making them easily accessible, eminently exchangable and never out of print. This should, in principle, elicit a hallelujah from authors, or at least the many who have written works that, while possessed of intrinsic value, have not succeeded in their role as commodities.

But utopian visions of an intellecutal gift economy will ultimately fail to nourish writers who must survive in the here and now of a commercial market. Though peer-to-peer gift economies might turn out in the long run to be financially lucrative, and in unexpected ways, we can’t realistically expect everyone to hold their breath and wait for that to happen. So we find ourselves at a crossroads where we must soon choose as a society either to clamp down (to preserve existing business models), liberalize (to clear the field for new ones), or compromise.

In her essay “Books in Time,” Berkeley historian Carla Hesse gives a wonderful overview of a similar debate over intellectual property that took place in 18th Century France, when liberal-minded philosophes — most notably Condorcet — railed against the state-sanctioned Paris printing monopolies, demanding universal access to knowledge for all humanity. To Condorcet, freedom of the press meant not only freedom from censorship but freedom from commerce, since ideas arise not from men but through men from nature (how can you sell something that is universally owned?). Things finally settled down in France after the revolution and the country (and the West) embarked on a historic compromise that laid the foundations for what Hesse calls “the modern literary system”:

The modern “civilization of the book” that emerged from the democratic revolutions of the eighteenth century was in effect a regulatory compromise among competing social ideals: the notion of the right-bearing and accountable individual author, the value of democratic access to useful knowledge, and faith in free market competition as the most effective mechanism of public exchange.

Barriers to knowledge were lowered. A system of limited intellectual property rights was put in place that incentivized production and elevated the status of writers. And by and large, the world of ideas flourished within a commercial market. But the question remains: can we reach an equivalent compromise today? And if so, what would it look like?  Creative Commons has begun to nibble around the edges of the problem, but love it as we may, it does not fundamentally alter the status quo, focusing as it does primarily on giving creators more options within the existing copyright system.

Creative Commons has begun to nibble around the edges of the problem, but love it as we may, it does not fundamentally alter the status quo, focusing as it does primarily on giving creators more options within the existing copyright system.

Which is why free software guru Richard Stallman announced in an interview the other day his unqualified opposition to the Creative Commons movement, explaining that while some of its licenses meet the standards of open source, others are overly conservative, rendering the project bunk as a whole. For Stallman, ever the iconoclast, it’s all or nothing.

But returning to our theme of compromise, I’m struck again by this idea of a tax on photocopiers, which suggests a kind of micro-economy where payments are made automatically and seamlessly in proportion to a work’s use. Someone who has done a great dealing of thinking about such a solution (though on a much more ambitious scale than library photocopiers) is Terry Fisher, an intellectual property scholar at Harvard who has written extensively on practicable alternative copyright models for the music and film industries (Ray and I first encountered Fisher’s work when we heard him speak at the Economics of Open Content Symposium at MIT last month).

The following is an excerpt from Fisher’s 2004 book, “Promises to Keep: Technology, Law, and the Future of Entertainment”, that paints a relatively detailed picture of what one alternative copyright scheme might look like. It’s a bit long, and as I mentioned, deals specifically with the recording and movie industries, but it’s worth reading in light of this discussion since it seems it could just as easily apply to electronic books:

The following is an excerpt from Fisher’s 2004 book, “Promises to Keep: Technology, Law, and the Future of Entertainment”, that paints a relatively detailed picture of what one alternative copyright scheme might look like. It’s a bit long, and as I mentioned, deals specifically with the recording and movie industries, but it’s worth reading in light of this discussion since it seems it could just as easily apply to electronic books:

….we should consider a fundamental change in approach…. replace major portions of the copyright and encryption-reinforcement models with a variant of….a governmentally administered reward system. In brief, here’s how such a system would work. A creator who wished to collect revenue when his or her song or film was heard or watched would register it with the Copyright Office. With registration would come a unique file name, which would be used to track transmissions of digital copies of the work. The government would raise, through taxes, sufficient money to compensate registrants for making their works available to the public. Using techniques pioneered by American and European performing rights organizations and television rating services, a government agency would estimate the frequency with which each song and film was heard or watched by consumers. Each registrant would then periodically be paid by the agency a share of the tax revenues proportional to the relative popularity of his or her creation. Once this system were in place, we would modify copyright law to eliminate most of the current prohibitions on unauthorized reproduction, distribution, adaptation, and performance of audio and video recordings. Music and films would thus be readily available, legally, for free.

Painting with a very broad brush…., here would be the advantages of such a system. Consumers would pay less for more entertainment. Artists would be fairly compensated. The set of artists who made their creations available to the world at large–and consequently the range of entertainment products available to consumers–would increase. Musicians would be less dependent on record companies, and filmmakers would be less dependent on studios, for the distribution of their creations. Both consumers and artists would enjoy greater freedom to modify and redistribute audio and video recordings. Although the prices of consumer electronic equipment and broadband access would increase somewhat, demand for them would rise, thus benefiting the suppliers of those goods and services. Finally, society at large would benefit from a sharp reduction in litigation and other transaction costs.

While I’m uncomfortable with the idea of any top-down, governmental solution, this certainly provides food for thought.

DRM and the damage done to libraries

A recent BBC article draws attention to widespread concerns among UK librarians (concerns I know are shared by librarians and educators on this side of the Atlantic) regarding the potentially disastrous impact of digital rights management on the long-term viability of electronic collections. At present, when downloads represent only a tiny fraction of most libraries’ circulation, DRM is more of a nuisance than a threat. At the New York Public library, for instance, only one “copy” of each downloadable ebook or audio book title can be “checked out” at a time — a frustrating policy that all but cancels out the value of its modest digital collection. But the implications further down the road, when an increasing portion of library holdings will be non-physical, are far more grave.

What these restrictions in effect do is place locks on books, journals and other publications — locks for which there are generally no keys. What happens, for example, when a work passes into the public domain but its code restrictions remain intact? Or when materials must be converted to newer formats but can’t be extracted from their original files? The question we must ask is: how can librarians, now or in the future, be expected to effectively manage, preserve and update their collections in such straightjacketed conditions?

This is another example of how the prevailing copyright fundamentalism threatens to constrict the flow and preservation of knowledge for future generations. I say “fundamentalism” because the current copyright regime in this country is radical and unprecedented in its scope, yet traces its roots back to the initially sound concept of limited intellectual property rights as an incentive to production, which, in turn, stemmed from the Enlightenment idea of an author’s natural rights. What was originally granted (hesitantly) as a temporary, statutory limitation on the public domain has spun out of control into a full-blown culture of intellectual control that chokes the flow of ideas through society — the very thing copyright was supposed to promote in the first place.

If we don’t come to our senses, we seem destined for a new dark age where every utterance must be sanctioned by some rights holder or licensing agent. Free thought isn’t possible, after all, when every thought is taxed. In his “An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?” Kant condemns as criminal any contract that compromises the potential of future generations to advance their knowledge. He’s talking about the church, but this can just as easily be applied to the information monopolists of our times and their new tool, DRM, which, in its insidious way, is a kind of contract (though one that is by definition non-negotiable since enforced by a machine):

But would a society of pastors, perhaps a church assembly or venerable presbytery (as those among the Dutch call themselves), not be justified in binding itself by oath to a certain unalterable symbol in order to secure a constant guardianship over each of its members and through them over the people, and this for all time: I say that this is wholly impossible. Such a contract, whose intention is to preclude forever all further enlightenment of the human race, is absolutely null and void, even if it should be ratified by the supreme power, by parliaments, and by the most solemn peace treaties. One age cannot bind itself, and thus conspire, to place a succeeding one in a condition whereby it would be impossible for the later age to expand its knowledge (particularly where it is so very important), to rid itself of errors, and generally to increase its enlightenment. That would be a crime against human nature, whose essential destiny lies precisely in such progress; subsequent generations are thus completely justified in dismissing such agreements as unauthorized and criminal.

We can only hope that subsequent generations prove more enlightened than those presently in charge.