Joy Weese Moll, a soon-to-be graduate of the School of Information Science and Learning Technologies at the University of Missouri, and author of the blog Wanderings of a Student Librarian, has written a useful overview of Google’s Print and Scholar initiatives – actually a session report from the Association of College & Research Libraries conference earlier this month. Summarized by Moll are suprisingly harmonious remarks by Adam Smith, product manager for Google’s library-related projects, and John Price Wilkin, a top librarian at the University of Michigan (and one of Google’s pilot partners).

“Smith made it very clear that this project is in its infancy. Google considers itself to be an international company and intends to participate in digitization projects in other countries and other languages. Smith acknowledged that Google cannot digitize everything. Rather, Google wants to be a catalyst for digitization efforts, not the only game in town. Google’s digitization project will help them build tools that will improve the searching of digital libraries created by universities, governments, and other organizations.”

Among other things, Wilkin points out that the mass digitization library collections “has already proven to be a factor in driving clarification of intellectual property rights, including the orphan copyright issue.”

Published in Cites and Insights. Link via Bibliotheke.

Category Archives: Libraries, Search and the Web

“the only group that can organize everything is everybody”

Some more thoughts on Clay Shirky‘s keynote lecture on “folksonomies” at the Interactive Multimedia Culture Expo this past weekend in New York (see earlier post, “as u like it – a networked bibliography“).

Shirky talks about the classification systems of libraries – think card catalogues. Each card provides taxonomical directions for locating a book on a library’s shelves. And like shelves, the taxonomies are rigid, hierarchical – “cleaving nature at the joints,” in his words. The rigidity of the shelf tends to fossilize cultural biases, and makes it difficult to adjust to changing political realities. The Library of Congress, for instance, devotes the same taxonomic space to the history of Switzerland and the Balkan Peninsula as it does to the history of all Africa and Asia. See the table below (source: Wikipedia).

Or take the end of the Cold War.. When the Soviet Union disintegrated, the world re-arranged itself. An old order was smashed. Dozens of political and cultural identities poured out of stasis. Imagine the re-shelving effort that was required! Librarians shuddered, knowing this was a task that far exceeded their physical and temporal resources. And so they opted to keep the books where they were, changing the section’s header to “the former Soviet Union.” Problem solved. Well, sort of.

When communication and transportation were slower, libraries had a chance of keeping up with the world. But the management of humanity’s paper memory has become too cumbersome and complex – too heavy – to register every nuance, shock, and twist of history and human thought. Now, with the web becoming our library, there is, quoting Shirky again, “no shelf,” and it’s possible to have more fluid, more flexible ways of classifying knowledge. But the web has been slow to realize this. Look at Yahoo!, which, since first appearing on the scene, has organized its content under dozens of categories, imposing the old shelf-based model. As a result, their home page is the very picture of information overload. Google, on the other hand, decided not to impose these hierarchies, hence their famously spartan portal. Given the speed and frequency with which we can document every moment of our lives in every corner of the world, in every conceivable media – and considering that this will only continue to increase – there is no way that the job of organizing it all can be left solely to professional classifiers. Shirky puts it succinctly: “the only group that can organize everything is everybody.”

That’s where folksonomy comes in – user-generated taxonomy built with metadata, such as tags. Everybody can apply tags that reflect their sense of how things should be organized – their own personal Dewey Decimal System. There is no “top level.” There are no folders. There is no shelf. Categories can overlap endlessly, like a sea of Venn diagrams. The question is, how do we prevent things from becoming incoherent? If there are as many classifications as there are footsteps through the world, then knowledge ceases to be a tool we can use. And though folksonomy frees us from the rigid, top-down hierarchies of the shelf, it subjects us to the brutal hierarchy of the web, which is time.

The web tends to privilege content that is new or recently updated. And tagging systems, in their present stage of development, are no different. Like blogs, tag searches place new content at the top, while the old stuff gets swiftly buried. As of this writing, there are nearly 24,000 photos on Flickr tagged with “China” (and this with Flickr barely a year old). You get the recent uploads first and must dig for anything older. Sure, you can run advanced searches on multiple tags to narrow the field, but how can you be sure you’ve entered the right tags to find everything that you’re looking for? With Flickr, it is by and large the photographers themselves that apply the tags, so we have to be mind readers to guess the more nuanced classifications. Clearly, we’ll need better tools if this is all going to work. Far from becoming obsolete, librarians may in fact become the most important people of all. It’s not difficult to imagine their role shifting from the management of paper archives to the management of tags. They are, after all, the original masters of metadata. Different schools of tagging could emerge and we would subscribe to the ones we most trust, or that mesh best with our own view of things. Librarians could become the sages of the web.

It’s easy to get preoccupied with the volume of information we’re dealing with today. But the issue of time, which I raised earlier, should also be foremost in our minds. If libraries were to shake as violently and often as the world, they would crumble. They are not newsrooms. They are not bazaars. Like writing, libraries create stable, legible forms out of swirling passions. They provide refuge. Their cool, peaceful depths enable analysis and abstraction. They provide an environment in which the world can appear at a distance, spread out on literate strands that may be read in calm and quiet. As a library, the web feels more like the real world – sometimes too much so. It throbs with life, with momentary desires, with sudden outbursts. It is hypersensitive to change. But things pile up, or vanish altogether. I may have the smartest, most intuitive tags in the world, but in a year they might become nothing more than headstones for dead links. It is ironic that with greater access to more knowledge than ever before, we tend to live in a perpetual present. If folksonomies are truly where we’re headed, then we must find ways to overcome the awful forgetfulness of the web. Otherwise, we may regret leaving the old, stubborn, but dependable shelf behind.

as u like it – a networked bibliography

This past weekend I attended some of the keynote lectures at the Interactive Multimedia Culture Expo at the Chelsea Art Museum in New York. Among the speakers was Clay Shirky, who gave a quick, energetic talk on “folksonomies” – user-generated taxonomies (i.e. tags) – and how they are changing, from the bottom up, the way we organize information. Folksonomies are still in an infant stage of development, and it remains to be seen how they will develop and refine themselves. Already, it is getting to be a bit confusing and overwhelming. We are in the process of building, collectively, one tag at a time, a massive library. Clearly, we need tools that will help us navigate it.

Something to watch is how folksonomies are converging with social software platforms like Flickr. What’s interesting is how communities form around specific interests – photos, for instance – and develop shared vocabularies. You also have the bookmarking model pioneered by del.icio.us, which essentially empowers each individual web user as a curator of links. People can link to your page, or subscribe with a feed reader. Eventually, word might spread of particular “editors” with particularly valuable content, organized particularly well. New forms of authority are thereby engendered.

Something to watch is how folksonomies are converging with social software platforms like Flickr. What’s interesting is how communities form around specific interests – photos, for instance – and develop shared vocabularies. You also have the bookmarking model pioneered by del.icio.us, which essentially empowers each individual web user as a curator of links. People can link to your page, or subscribe with a feed reader. Eventually, word might spread of particular “editors” with particularly valuable content, organized particularly well. New forms of authority are thereby engendered.

Shirky mentioned an interesting site that is sort of a cross between these two models. CiteULike takes the tag-based bookmark classification system of del.icio.us and applies it exclusively to papers in academic journals, thereby carving out a defined community of interest, like Flickr.

“CiteULike is a free service to help academics to share, store, and organise the academic papers they are reading. When you see a paper on the web that interests you, you can click one button and have it added to your personal library. CiteULike automatically extracts the citation details, so there’s no need to type them in yourself. It all works from within your web browser. There’s no need to install any special software.”

Essentially, CiteULike is an enormous networked bibliography. On the first page, recently posted papers are listed under the header, “everyone’s library.” To the right is an array of the most popular tags, varying in size according to popularity (like in Flickr). Each tag page has an RSS feed that you can syndicate. You can also form or join groups around a specific subject area. As of this writing, there are articles bookmarked from 6,498 journals, primarily in biology in medicine, “but there is no reason why, say, history or philosophy bibliographies should not be equally prevalent.” So says Richard Cameron, who wrote the site this past November and is its sole operator. Citations are automatically extracted for bookmarked articles, but only if they come from a source that CiteULike supports (list here, scroll down). You can enter metadata manually if you are are not submitting from a vetted source, but your link will appear only on your personal bookmarks page, not on the homepage or in tag searches. This is to maintain a peer review standard for all submitted links, and to guard against “lunatics.” CiteULike says it is looking to steadily expand its pool of supported sources.

CiteULike might eventually fizzle out. Or it might mushroom into something massively popular (it’s already running in five additional languages). Perhaps it will merge with other social software platforms into a more comprehensive folksonomic universe. Perhaps Google will buy it up. It’s impossible to predict. But CiteULike is a valuable experiment in harnessing the power of focused communities, and in creating the tools for navigating our nascent library. It might also solve some of the problems put forth in Kim’s post, “weaving textbooks into the web.” Worth keeping an eye on.

find it rip it mix it share it

That’s the slogan for the just-launched Creative Archive License Group – a DRM-free audio/video/still image repository maintained by the BBC to provide “fuel for the creative nation.” Other members include Channel 4, Open University, and the British Film Institute (bfi). Imagine if the big three US networks, PBS, NPR and the MOMA film archive were to do such a thing…

amazon: inching toward semantic

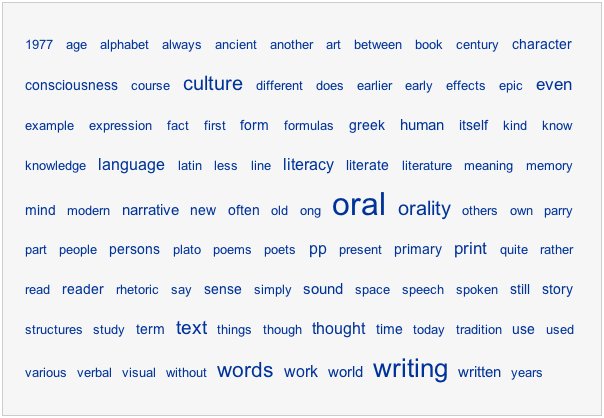

Sometime in the last few days, Amazon.com unveiled three new features for its Inside the Book search: “books on related topics,” a “100 most frequently used” concordance (above is the concordance for Orality and Literacy by Walter J. Ong), and “text stats.” The stats are pretty funny – in addition to page, word and character count, they measure a book’s “complexity” as well as its “readability” according to three established indexes, including the famous and amusingly named “Fog Index” (as though it rated the density of mental fog between a reader and a book). It also includes so-called “fun stats” like words per dollar and words per ounce.

Some of these features seem a little trivial, but there’s no denying that Amazon is moving surely and steadily toward a comprehensive semantic browsing system (other recent innovations are Statistically Improbable Phrases (SIPS) and Citations). Though still crude compared to what it might eventually become, you can begin to glimpse the pleasures and uses it will afford. Amazon can never replace the social and tactile pleasures of browsing a physical bookstore, but it’s doing a good job at making the virtual bookstore a more exciting place.

simple answers to simple questions

Looking for simple facts on the web can be a frustrating business. Over time, we bookmark sites that reliably deliver the goods – things like basic geographical data, conversion scales for measurements, biographical summaries, or anything else that we need to quickly grab, plug in, and move on. But it all takes much longer than it should, and in looking for such things, we’re plagued as much by the nuance of internet search as by its imprecision. It’s all part of learning how to deal with this massive web we’ve created, and the state of blindness to which it reduces us. Search engines are really the only tool we have for groping through a pitch black sea of information, where the ineluctable modality is meaning, not the visible (for more on this, read Steven Pemberton’s talk from the Decade of Web Design conference, which if:book attended this January in Amsterdam).

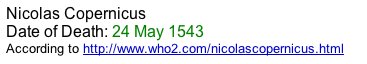

Well Google has helped us to see, just a little bit better, the little nuggets and factual crystals that we so often sift for in our blindness – by unveiling a new Q&A feature for basic web search (article via Bibliotheke). Plug in a search like “earth distance sun,” or “copernicus date of death,” and you get exactly what you’re looking for right above the stack of general results:

or

It’s the kind of small, thoughtful innovation that makes you appreciate Google’s attention to detail and sensitivity to the problem of blindness. Other search engines like Ask Jeeves offer a similar feature, but Google includes the information’s source (a source they’ve vetted and deemed reliable) and a link to that page. For example, in the case of basic geography and demographics, the link might be to the CIA’s World Factbook. Even if you just grab the fact and run, it’s comforting to have seen a trustworthy citation, though some might grumble about the CIA.

It would be fantastic if this kind of quick fact extraction could be tailored to different search needs. Imagine a “writer’s search toolbox” combining every conceivable reference resource that an author might need. Enter “synonym for think” and right at the top you get an entire thesaurus search result: “analyze, appraise, appreciate, brood, cerebrate, chew, cogitate, comprehend, conceive….” Enter “idiom with humble” and you get “eat humble pie,” “Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home,” etc. Or search for rhymes, poetic forms, grammar guidelines, literary terms, writer bios, quotes, etymologies – anything. It’s good news that search is being refined in this way, and competition among giants seems, in the end, to be good for the average web browser. Whatever helps us spend less time scouring and more time on the things that are important to us.

baking google’s cookies

![]() Bibliotheke points to the recent adventures of Greg Duffy, a talented Texas college student who figured out how to read entire copyrighted books in Google Print by “baking” the cookies (data sent from to your computer from a web browser to store preferences for specific sites and pages) Google uses to impose search limits on protected material. Duffy took on the challenge largely out of curiousity, but doesn’t deny that he fantasizes about his chutzpah landing him a job at Google. He hasn’t been hired yet, but he did manage to attract a great deal of attention and over 10,000 hits to his site from more than 60 countries. And in the sudden commotion, he mysteriously disappeared from Google’s web search results, only to reappear shorly after Google Print had been fixed to repel the hack. Any connection between the two events was cheerily denied by a Google representative writing in the comments on Duffy’s blog under the nom de plume “Google Guy.” Conspiracy theories abound, but Duffy has retained an excellent sense of humor throughout the whole affair, and still makes no secret of his hopes that sheer audacity and display of chops might yet get him hired by the juggernaut he so admires and loves to tease.

Bibliotheke points to the recent adventures of Greg Duffy, a talented Texas college student who figured out how to read entire copyrighted books in Google Print by “baking” the cookies (data sent from to your computer from a web browser to store preferences for specific sites and pages) Google uses to impose search limits on protected material. Duffy took on the challenge largely out of curiousity, but doesn’t deny that he fantasizes about his chutzpah landing him a job at Google. He hasn’t been hired yet, but he did manage to attract a great deal of attention and over 10,000 hits to his site from more than 60 countries. And in the sudden commotion, he mysteriously disappeared from Google’s web search results, only to reappear shorly after Google Print had been fixed to repel the hack. Any connection between the two events was cheerily denied by a Google representative writing in the comments on Duffy’s blog under the nom de plume “Google Guy.” Conspiracy theories abound, but Duffy has retained an excellent sense of humor throughout the whole affair, and still makes no secret of his hopes that sheer audacity and display of chops might yet get him hired by the juggernaut he so admires and loves to tease.

It’s a bit tech-heavy, but it’s worth reading his post and the updates that follow, if for no other reason than for his amusing riff on the cookie motif.

“So recently I wrote some software to grab and store up a bunch of cookies, keep them for more than 24 hours, and then automate searching for pages by this method. If I wanted to view page 100, the software would search for it and attempt to extract the image with a regular expression. If that doesn’t work, it will search for page 99 and extract the “next page” link to get to page 100. It will continue doing this for page 101, 98, and 102 until it finds the correct page. Whenever a cookie would hit the hard limit, I’d replace it with a new cookie from the queue. By grabbing the “next” and “previous” links automatically in this “inductive” fashion and using the search for skipping, I could view an entire book on Google Print with one click every time. I later modified the software to spit out a PDF of the book. I used simple components like GoogleCookie (cookie with accessible properties), GoogleCookieOven (queue with “baking time”, i.e. it only pops when the head of the queue is old enough to get the ability to search), and GoogleCookieBaker (thread that keeps the oven full of baking cookies by querying Google for new ones when the number drops below a certain threshold).”

chirac vs. google

![]() French President Jacques Chirac has instructed the Bibliothè que Nationale de France to “draw up a plan” for a comprehensive online library of European literature to counter what is seen as the inevitably Anglo-Saxon bias of Google Print (see “non, merci”).

French President Jacques Chirac has instructed the Bibliothè que Nationale de France to “draw up a plan” for a comprehensive online library of European literature to counter what is seen as the inevitably Anglo-Saxon bias of Google Print (see “non, merci”).

Reuters story: Chirac Rivals Google with French Online Book Plan

l.i. library lends ipods

Boing Boing points to a library in Long Island that has recently started lending mp3 audio books on iPod shuffles, even throwing in casette adapters and FM transmitters for listening in the car. The library claims that they are saving a lot of money in the long run, since mp3 audio books cost significantly less than books on cd.

>>Wired story

non, merci

Jean-Noel Jeanneney, the head of France’s national library (BNF), has raised a “battle cry” (Le Figaro) against the cultural and linguistic imperialism of America. But this time, it’s not about Big Macs and slang coming to massacre the French langauge. It’s about Google and its plans to digitize libraries, which, Jeanneney says, will put a distinctly anglo stamp on the greater part of the world’s knowledge (Reuters). Encouraging Europe to take part in this massive project seems like a good idea – for the sake of diversity, but more important, to offer a possible alternative to Google’s approach, which was devised in the absence of any real competition. Google Print‘s interface is limited to a snapshot tour of a book, with minimal search capabilities. They’re essentially doing for books what A9 is doing for streets, with souped-up scanners instead of trucks with camera mounts. It’s a browsing tool and not much more.

Google’s stock is soaring not only because it is a great engine, but also because it has pioneered a new kind of search-based advertising. There’s been a lot of high-minded conjecture (e.g.) as to what Google Print might mean for humanity – rhapsodic allusions to Borges and the library of Alexandria. But the great global library of our dreams probably won’t be created by Google. You could say that we are all creating it, that the web is that library. But without getting too breathless, think of the fact that with each passing year we move further and further into a paperless world. We will need well-designed electronic books in a well-designed electronic library, or matrix of libraries. So it’s heartening that a serious institution like BNF wants to get in on the game. Maybe they can do better. A good indication that they could is their recently announced project (sorry, only French link) to build a free online archive of 130 years of French newspapers and periodicals – 29 publications in total, running from 1814 to 1944. But then again, perhaps they simply want to secure a place in Google’s illustrious coalition of the willing: Harvard, Oxford, U. of Michigan, Stanford, and the New York Public Library.