We’ve got a column in the latest Publishers Weekly. An appeal to publishers to start thinking about books in a network context.

Category Archives: google_book_search

good discussion(s) of kevin kelly article

In the New York Times own book discussion forum, one rirutsky opines eloquently on the problems with Kelly’s punch-drunk corporate optimism:

…what I find particularly problematic is the way that Kelly’s “analysis”–as well as most of the discussion of it–omits any serious mention of what is actually at stake in the utopian scheme of a universal library (which Borges, by the way, does not promote, but debunks). It has little to do with enabling creativity, but rather, with enabling greater corporate profits. Kelly is actually most close to the mark when [he] characterizes the conflict over digital books as a conflict between two business models. Of course, one gets the impression from some of Kelly’s writings that for him business and creativity are more or less the same thing….

….A more serious consideration of these issues would move away from the “old” binary antagonisms that Kelly outlines (surely, these are a relic of a pre-digital age) and think seriously about how society at large is changed by digital technologies and techniques. Who has the right to copy or to make use of data and who does not? In a world of such vast informational clutter, doesn’t power accrue to those who can afford to advertise? It is worth remembering, too, that searching is not, after all, a value-free operation. Who ultimately will control the searching and indexing of digital information? Should the government–or private corporations–be allowed to data mine the searches that people make? In short, who benefits and who loses from these technological changes? Where, precisely, is power consolidated?

Kelly does not even begin to deal with these sorts of serious social issues.

And from a typically immense Slashdot thread (from highlights conveniently collected by Branko Collin at Teleread) — this comes back to the “book is reading you” question:

Will all these books and articles require we login to view them first? I think having every book, article, movie, song, etc available for use anytime is a great idea and important for society but I don’t want to have to login and leave a paper trail of everything I’m looking at.

And we have our own little thread going here.

if:book in library journal (and kevin kelly in n.y. times)

The Institute is on the cover of Library Journal this week! A big article called “The Social Life of Books,” which gives a good overview of the intersecting ideas and concerns that we mull over here daily. It all started, actually, with that little series of posts I wrote a few months back, “the book is reading you” (parts 3, 2 and 1), which pondered the darker implications of Google Book Search and commercial online publishing. The article is mostly an interview with me, but it covers ideas and subjects that we’ve been working through as a collective for the past year and a half. Wikipedia, Google, copyright, social software, networked books — most of our hobby horses are in there.

The Institute is on the cover of Library Journal this week! A big article called “The Social Life of Books,” which gives a good overview of the intersecting ideas and concerns that we mull over here daily. It all started, actually, with that little series of posts I wrote a few months back, “the book is reading you” (parts 3, 2 and 1), which pondered the darker implications of Google Book Search and commercial online publishing. The article is mostly an interview with me, but it covers ideas and subjects that we’ve been working through as a collective for the past year and a half. Wikipedia, Google, copyright, social software, networked books — most of our hobby horses are in there.

I also think the article serves as a nice complement (and in some ways counterpoint) to Kevin Kelly’s big article on books and search engines in yesterday’s New York Times Magazine. Kelly does an excellent job outlining the thorny intellectual property issues raised by Google Book Search and the internet in general. In particular, he gives a very lucid explanation of the copyright “orphan” issue, of which most readers of the Times are probably unaware. At least 75% of the books in contention in Google’s scanning effort are works that have been pretty much left for dead by the publishing industry: works (often out of print) whose copyright status is unclear, and for whom the rights holder is unknown, dead or otherwise prohibitively difficult to contact. Once publishers’ and authors’ groups sensed there might finally be a way to monetize these works, they mobilized a legal offensive.

Kelly argues convincingly that not only does Google have the right to make a transformative use of these works (scanning them into a searchable database), but that there is a moral imperative to do so, since these works will otherwise be left forever in the shadows. That the Times published such a progressive statement on copyright (and called it a manifesto no less) is to be applauded. That said, there are other things I felt were wanting in the article. First, at no point does Kelly question whether private companies such as Google ought to become the arbiter of all the world’s information. He seems pretty satisfied with this projected outcome.

And though the article serves as a great introduction to how search engines will revolutionize books, it doesn’t really delve into how books themselves — their form, their authorship, their content — might evolve. Interlinked, unbundled, tagged, woven into social networks — he goes into all that. But Kelly still conceives of something pretty much like a normal book (a linear construction, in relatively fixed form, made of pages) that, like Dylan at Newport in 1965, has gone electric. Our article in Library Journal goes further into the new networked life of books, intimating a profound re-jiggering of the relationship between authors and readers, and pointing to new networked modes of reading and writing in which a book is continually re-worked, re-combined and re-negotiated over time. Admittedly, these ideas have been developed further on if:book since I wrote the article a month and a half ago (when a blogger writes an article for a print magazine, there’s bound to be some temporal dissonance). There’s still a very active thread on the “defining the networked book” post which opens up many of the big questions, and I think serves well as a pre-published sequel to the LJ interview. We’d love to hear people’s thoughts on both the Kelly and the LJ pieces. Seems to make sense to discuss them in the same thread.

the social life of books

One of the most exciting things about Sophie, the open-source software the institute is currently developing, is that it will enable readers and writers to have conversations inside of books — both live chats and asynchronous exchanges through comments and social annotation. I touched on this idea of books as social software in my most recent “The Book is Reading You” post, and we’re exploring it right now through our networked book experiments with authors Mitch Stephens, and soon, McKenzie Wark, both of whom are writing books and opening up the process (with a little help from us) to readers. It’s a big part of our thinking here at the institute.

Catching up with some backlogged blog reading, I came across a little something from David Weinberger that suggests he shares our enthusiasm:

I can’t wait until we’re all reading on e-books. Because they’ll be networked, reading will become social. Book clubs will be continuous, global, ubiquitous, and as diverse as the Web.

And just think of being an author who gets to see which sections readers are underlining and scribbling next to. Just think of being an author given permission to reply.

I can’t wait.

Of course, ebooks as currently envisioned by Google and Amazon, bolted into restrictive IP enclosures, won’t allow for this kind of exchange. That’s why we need to be thinking hard right now about an alternative electronic publishing system. It may seem premature to say this — now, when electronic books are a marginal form — but before we know it, these companies will be the main purveyors of all media, including books, and we’ll wonder what the hell happened.

academic publishing as “gift culture”

John Holbo has an excellent piece up on the Valve that very convincingly argues the need to reinvent scholarly publishing as a digital, networked system. John will be attending a meeting we’ve organized in April to discuss the possible formation of an electronic press — read his post and you’ll see why we’ve invited him.

It was particularly encouraging, in light of recent discussion here, to see John clearly grasp the need for academics to step up to the plate and take into their own hands the development of scholarly resources on the web — now more than ever, as Google, Amazon are moving more aggressively to define how we find and read documents online:

…it seems to me the way for academic publishing to distinguish itself as an excellent form – in the age of google – is by becoming a bastion of ‘free culture’ in a way that google book won’t. We live in a world of Amazon ‘search inside’, but also of copyright extension and, in general, excessive I.P. enclosures. The groves of academe are well suited to be exemplary Creative Commons. But there is no guarantee they will be. So we should work for that.

googlezon and the publishing industry: a defining moment for books?

Yesterday Roger Sperberg made a thoughtful comment on my latest Google Books post in which he articulated (more precisely than I was able to do) the causes and potential consequences of the publisher’s quest for control. I’m working through these ideas with the thought of possibly writing an article, so I’m reposting my response (with a few additions) here. Would appreciate any feedback…

What’s interesting is how the Google/Amazon move into online books recapitulates the first flurry of ebook speculation in the mid-to-late 90s. At that time, the discussion was all about ebook reading devices, but then as now, the publish industry’s pursuit of legal and techological control of digital books seemed to bring with it a corresponding struggle for control over the definition of digital books — i.e. what is the book going to become in the digital age? The word “ebook” — generally understood as a digital version of a print book — is itself part of this legacy of trying to stablize the definition of books amid massively destablizing change. Of course the problem with this is that it throws up all sorts of walls — literal and conceptual — that close off avenues of innovation and rob books of much of their potential enrichment in the electronic environment.

Clifford Lynch described this well in his important 2001 essay “The Battle to Define to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World”:

Clifford Lynch described this well in his important 2001 essay “The Battle to Define to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World”:

…e-book readers may be the price that the publishing industry imposes, or tries to impose, on consumers, as part of the bargain that will make large numbers of interesting works available in electronic form. As a by-product, they may well constrain the widespread acceptance of the new genres of digital books and the extent to which they will be thought of as part of the canon of respectable digital “printed” works.

A similar bargain is being struck now between publishers and two of the great architects of the internet: Google and Amazon. Naturally, they accept the publishers’ uninspired definition of electronic books — highly restricted digital facsimiles of print books — since it guarantees them the most profit now. But it points in the long run to a malnourished digital culture (and maybe, paradoxically, the persistence of print? since paper books can’t be regulated so devilishly).

As these companies come of age, they behave less and less like the upstart innovators they originally were, and more like the big corporations they’ve become. We see their grand vision (especially Google’s) contract as the focus turns to near-term success and the fluctuations of stock. It creates a weird paradox: Google Book Search totally revolutionizes the way we search and find connections between books, but amounts to a huge setback in the way we read them.

(For those of you interested in reading Lynch’s full essay, there’s a TK3 version that is far more comfortable to read than the basic online text. Click the image above or go here to download. You’ll have to download the free TK3 Reader first, which takes about 10 seconds. Everything can be found at the above link).

the book is reading you, part 3

News broke quietly a little over a week ago that Google will begin selling full digital book editions from participating publishers. This will not, Google makes clear, extend to books from its Library Project — still a bone of contention between Google and the industry groups that have brought suit against it for scanning in-copyright works (75% of which — it boggles the mind — are out of print).

Let’s be clear: when they say book, they mean it in a pretty impoverished sense. Google’s ebooks will not be full digital editions, at least not in the way we would want: with attention paid to design and the reading experience in general. All you’ll get is the right to access the full scanned edition online.

Let’s be clear: when they say book, they mean it in a pretty impoverished sense. Google’s ebooks will not be full digital editions, at least not in the way we would want: with attention paid to design and the reading experience in general. All you’ll get is the right to access the full scanned edition online.

Much like Amazon’s projected Upgrade program, you’re not so much buying a book as a searchable digital companion to the print version. The book will not be downloadable, printable or shareable in any way, save for inviting a friend to sit beside you and read it on your screen. Fine, so it will be useful to have fully searchable texts, but what value is there other than this? And what might this suggest about the future of publishing as envisioned by companies like Google and Amazon, not to mention the future of our right to read?

About a month ago, Cory Doctorow wrote a long essay on Boing Boing exhorting publishers to wake up to the golden opportunities of Book Search. Not only should they not be contesting Google’s fair use claim, he argued, but they should be sending fruit baskets to express their gratitude. Allowing books to dwell in greater numbers on the internet saves them from falling off the digital train of progress and from losing relevance in people’s lives. Doctorow isn’t talking about a bookstore (he wrote this before the ebook announcement), or a full-fledged digital library, but simply a searchable index — something that will make books at least partially functional within the social sphere of the net.

This idea of the social life of books is crucial. To Doctorow it’s quite plain that books — as entertainment, as a diversion, as a place to stick your head for a while — are losing ground in a major way not only to electronic media like movies, TV and video games (that’s been happening for a while), but to new social rituals developing on the net and on portable networked devices.

Though print will always offer inimitable pleasures, the social life of media is moving to the network. That’s why we here at if:book care so much about issues, tangential as they may seem to the future of the book, like network neutrality, copyright and privacy. These issues are of great concern because they make up the environment for the future of reading and writing. We believe that a free, neutral network, a progressive intellectual property system, and robust safeguards for privacy are essential conditions for an enlightened digital age.

We also believe in understanding the essence of the new medium we are in the process of inventing, and about understanding the essential nature of books. The networked book is not a block on a shelf — it is a piece of social software. A web of revisions, interactions, annotations and references. “A piece of intellectual territory.” It can’t be measured in copies. Yet publishers want electronic books to behave like physical objects because physical objects can be controlled. Sales can be recorded, money counted. That’s why the electronic book market hasn’t materialized. Partly because people aren’t quite ready to begin reading books on screens, but also because publishers have been so half-hearted about publishing electronically.

They can’t even begin to imagine how books might be enhanced and expanded in a digital environment, so terrified are they of their entire industry being flushed down the internet drain — with hackers and pirates cannibalizing the literary system. To them, electronic publishing is grit your teeth and wait for the pain. A book is a PDF, some DRM and a prayer. Which is why they’ve reacted so heavy-handedly to Google’s book project. If they lose even a sliver of control, so they are convinced, all hell could break loose.

But wait! Google and Amazon are here to save the day. They understand the internet (naturally — they helped invent it). They understand the social dimension of online spaces. They know how to harness network effects and how to read the embedded desires of readers in the terms and titles for which they search. So they understand the social life of books on the network, right? And surely they will come up with a vision for electronic publishing that is both profitable for the creators and every bit as rich as the print culture that preceded it. Surely the future of the book lies with them?

Sadly, judging by their initial moves into electronic books, we should hope it does not. Understanding the social aspect of the internet also enables you to cunningly restrict it, more cunningly than any print publishers could figure out how to do.

Sadly, judging by their initial moves into electronic books, we should hope it does not. Understanding the social aspect of the internet also enables you to cunningly restrict it, more cunningly than any print publishers could figure out how to do.

Yes, they’ll give you the option of buying a book that lives its life on line, but like a chicken in a poultry plant, packed in a dark crate stuffed with feed tubes, it’s not much of a life. Or better, let’s evaluate it in the terms of a social space — say, a seminar room or book discussion group. In a Google/Amazon ebook you will not be allowed to:

– discuss

– quote

– share

– make notes

– make reference

– build upon

This is the book as antisocial software. Reading is done in solitary confinement, closely monitored by the network overseers. Google and Amazon’s ebooks are essentially, as David Rothman puts it on Teleread, “in a glass case in a museum.” Get too close to the art and motion sensors trigger the alarm.

So ultimately we can’t rely on the big technology companies to make the right decisions for our future. Google’s “fair use” claim for building its books database may be bold and progressive, but its idea of ebooks clearly is not. Even looking solely at the searchable database component of the project, let’s not forget that Google’s ranking system (as Siva Vaidhyanathan has repeatedly reminded us) is non-transparent. In other words, when we do a search on Google Books, we don’t know why the results come up in the order that they do. It’s non-transparent librarianship. Information mystery rather than information science. What secret algorithmic processes are reordering our knowledge and, over time, reordering our minds? And are they immune to commercial interests? And shouldn’t this be of concern to the libraries who have so blithely outsourced the task of digitization? I repeat: Google will make the right choices only when it is in its interest to do so. Its recent actions in China should leave no doubt.

Perhaps someday soon they’ll ease up a bit and let you download a copy, but that would only be because the hardware we are using at that point will be fitted with a “trusted computing” module, which which will monitor what media you use on your machine and how you use it. At that point, copyright will quite literally be the system. Enforcement will be unnecessary since every potential transgression will be preempted through hardwired code. Surveillance will be complete. Control total. Your rights surrendered simply by logging on.

google buys writely, or, the book is reading you, part 2

Last week Google bought Upstartle, a small company that created an online word processing program called Writely.  Writely is like a stripped-down Microsoft Word, with the crucial difference that it exists entirely online, allowing you to write, edit, publish and store documents (individually or in collaboration with others) on the network without being tied to any particular machine or copy of a program. This evidently confirms the much speculated-about Google office suite with Writely and Gmail as cornerstone, and presumably has Bill Gates shitting bricks .

Writely is like a stripped-down Microsoft Word, with the crucial difference that it exists entirely online, allowing you to write, edit, publish and store documents (individually or in collaboration with others) on the network without being tied to any particular machine or copy of a program. This evidently confirms the much speculated-about Google office suite with Writely and Gmail as cornerstone, and presumably has Bill Gates shitting bricks .

Back in January, I noted that Google requires you to be logged in with a Google ID to access full page views of copyrighted works in its Book Search service. Which gave me the eerie feeling that the books are reading us: capturing our clickstreams, keywords, zip codes even — and, of course, all the pages we’ve traversed. This isn’t necessarily a new thing. Amazon has been doing it for a while and has built a sophisticated personalized recommendation system out of it — a serendipity engine that makes up for some of the lost pleasures of browsing a physical store. There it seems fairly harmless, useful actually, though it depends on who you ask (my mother says it gives her the willies). Gmail is what has me spooked. The constant sprinkle of contextual ads in the margin attaching like barnacles to my bot-scoured correspondences. Google’s acquisition of Writely suggests that things will only get spookier.

I’ve been a webmail user for the past several years, and more recently a blogger (which is a sort of online word processing) but I’m uneasy about what the Writely-Google union portends — about moving the bulk of my creative output into a surveilled space where the actual content of what I’m working on becomes an asset of the private company that supplies the tools.

Imagine you’re writing your opus and ads, drawn from words and themes in your work, are popping up in the periphery. Or the program senses line breaks resembling verse, and you get solicited for publication — before you’ve even finished writing — in one of those suckers’ poetry anthologies.  Leave the cursor blinking too long on a blank page and it starts advertising cures for writers’ block. Copy from a copyrighted source and Writely orders you to cease and desist after matching your text in a unique character string database. Write an essay about terrorists and child pornographers and you find yourself flagged.

Leave the cursor blinking too long on a blank page and it starts advertising cures for writers’ block. Copy from a copyrighted source and Writely orders you to cease and desist after matching your text in a unique character string database. Write an essay about terrorists and child pornographers and you find yourself flagged.

Reading and writing migrated to the computer, and now the computer — all except the basic hardware — is migrating to the network. We here at the institute talk about this as the dawn of the networked book, and we have open source software in development that will enable the writing of this new sort of born-digital book (online word processing being just part of it). But in many cases, the networked book will live in an increasingly commercial context, tattooed and watermarked (like our clothing) with a dozen bubbly logos and scoured by a million mechanical eyes.

Suddenly, that smarmy little paper clip character always popping up in Microsoft Word doesn’t seem quite so bad. Annoying as he is, at least he has an off switch. And at least he’s not taking your words and throwing them back at you as advertisements — re-writing you, as it were. Forgive me if I sound a bit paranoid — I’m just trying to underscore the privacy issues. Like a frog in a pot of slowly heating water, we don’t really notice until it’s too late that things are rising to a boil. Then again, being highly adaptive creatures, we’ll more likely get accustomed to this softer standard of privacy and learn to withstand the heat — or simply not be bothered at all.

the book is reading you

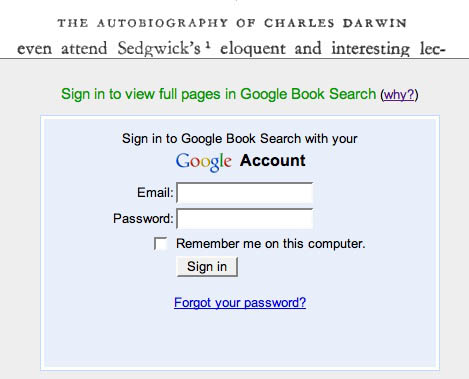

I just noticed that Google Book Search requires users to be logged in on a Google account to view pages of copyrighted works.

They provide the following explanation:

Why do I have to log in to see certain pages?

Because many of the books in Google Book Search are still under copyright, we limit the amount of a book that a user can see. In order to enforce these limits, we make some pages available only after you log in to an existing Google Account (such as a Gmail account) or create a new one. The aim of Google Book Search is to help you discover books, not read them cover to cover, so you may not be able to see every page you’re interested in.

So they’re tracking how much we’ve looked at and capping our number of page views. Presumably a bone tossed to publishers, who I’m sure will continue suing Google all the same (more on this here). There’s also the possibility that publishers have requested information on who’s looking at their books — geographical breakdowns and stats on click-throughs to retailers and libraries. I doubt, though, that Google would share this sort of user data. Substantial privacy issues aside, that’s valuable information they want to keep for themselves.

That’s because “the aim of Google Book Search” is also to discover who you are. It’s capturing your clickstreams, analyzing what you’ve searched and the terms you’ve used to get there. The book is reading you. Substantial privacy issues aside, (it seems more and more that’s where we’ll be leaving them) Google will use this data to refine Google’s search algorithms and, who knows, might even develop some sort of personalized recommendation system similar to Amazon’s — you know, where the computer lists other titles that might interest you based on what you’ve read, bought or browsed in the past (a system that works only if you are logged in). It’s possible Google is thinking of Book Search as the cornerstone of a larger venture that could compete with Amazon.

There are many ways Google could eventually capitalize on its books database — that is, beyond the contextual advertising that is currently its main source of revenue. It might turn the scanned texts into readable editions, hammer out licensing agreements with publishers, and become the world’s biggest ebook store. It could start a print-on-demand service — a Xerox machine on steroids (and the return of Google Print?). It could work out deals with publishers to sell access to complete online editions — a searchable text to go along with the physical book — as Amazon announced it will do with its Upgrade service. Or it could start selling sections of books — individual pages, chapters etc. — as Amazon has also planned to do with its Pages program.

Amazon has long served as a valuable research tool for books in print, so much so that some university library systems are now emulating it. Recent additions to the Search Inside the Book program such as concordances, interlinked citations, and statistically improbable phrases (where distinctive terms in the book act as machine-generated tags) are especially fun to play with. Although first and foremost a retailer, Amazon feels more and more like a search system every day (and its A9 engine, though seemingly always on the back burner, is also developing some interesting features). On the flip side Google, though a search system, could start feeling more like a retailer. In either case, you’ll have to log in first.

last week: wikipedia, r kelly, gaming and google panels, and more…

Here’s an overview of what we’ve been posting over the last week. As well, a few of us having been talking about ways to graphically represent text, so I thought I would include a mind map of this overview.

As a follow up to the increasingly controversial wikipedia front, Daniel Brandt uncovered that Brian Chase posted false information about John Seignthaler that was reported here last week. To add fuel to the fire, Nature weighed in that Encyclopedia Britannica may not be as reliable as Wikipedia.

Business Week noted a possible future of pricing for data transfer. Currently, carries such as phone and cable companies are developing technology to identify and control what types of media (voice, images, text or video) are being uploaded. This ability opens the door to being able to charge for different uses of data transfer, which would have a huge impact on uploading content for personal creative use of the internet.

Liz Barry and Bill Wetzel shared some of their experiences from their “Talk to Me” Project. With their “talk to me” sign in tow, they travel around New York and the rest of the US looking for conversation. We were impressed at how they do not have a specific agenda besides talking to people. In the mediated age, they are not motivated by external political/ religious/ documentary intentions. What they do document is available on their website, and we look forward to see what they come up with next.

The Google Book Search debate continues as well, via a panel discussion hosted by the American Bar Association. Interestingly, publishers spoke as if the wide scale use of ebooks is imminent. More importantly and even if this particular case settles out of court, the courts have a pressing need to define copyright and fair use guidelines for these emerging uses.

With the protest of the WTO meetings in Hong Kong this past week, new journalism forms took one step forward. The website Curbside @ WTO covered the meetings with submissions from journalism students, bloggers and professional journalists.

McDonalds filed a patent which suggests that it intends to offer clips of movies instead of the traditional toys in their kids oriented Happy Meals. Lisa pondered if a video clip can successfully replace a toy, and if it does, what the effects on children’s imaginations might be.

R. Kelly’s experiments in form and the “serial song” through his Trapped in the Closet recordings. While R Kelly has varying success in this endeavor, Dan compared the experience of not only the serial novel, but also Julie Powell’s foray into transferring her blog into book form and what she might have learned from R. Kelly (its hard to make unified pieces maintain an overall coherency.)

The world of academic publishing was challenged with a proposal calling to create an electronic academic press. This segment seems especially ripe for the shift to digital publishing as many journals with small circulations face raising printing and production costs.

Sol and others from the institute attended “Making Games Matter,” a panel with contributors from The Game Design Reader: A Rules of Play Anthology, edited by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. The discussion covered among other things: involving the academy in creating a discourse for gaming and game design, obstacles in studying and creating games, and the game “industry” itself. The book and panel called out for games and gaming to undergo a formal study akin to the novel and the experience of reading. Also, in the gaming world, the class economics of the real and virtual began to emerge as a Chinese firm pays employees to build up characters in MMOGs to sell to affluent gamers.