New partners and new features. Google has been busy lately building up Book Search. On the institutional end, Ghent, Lausanne and Mysore are among the most recent universities to hitch their wagons to the Google library project. On the user end, the GBS feature set continues to expand, with new discovery tools and more extensive “about” pages gathering a range of contextual resources for each individual volume.

Recently, they extended this coverage to books that haven’t yet been digitized, substantially increasing the findability, if not yet the searchability, of thousands of new titles. The about pages are similar to Amazon’s, which supply book browsers with things like concordances, “statistically improbably phrases” (tags generated automatically from distinct phrasings in a text), textual statistics, and, best of all, hot-linked lists of references to and from other titles in the catalog: a rich bibliographic network of interconnected texts (Bob wrote about this fairly recently). Google’s pages do much the same thing but add other valuable links to retailers, library catalogues, reviews, blogs, scholarly resources, Wikipedia entries, and other relevant sites around the net (an example). Again, many of these books are not yet full-text searchable, but collecting these resources in one place is highly useful.

It makes me think, though, how sorely an open source alternative to this is needed. Wikipedia already has reasonably extensive articles about various works of literature. Library Thing has built a terrific social architecture for sharing books. There are a great number of other freely accessible resources around the web, scholarly database projects, public domain e-libraries, CC-licensed collections, library catalogs.

Could this be stitched together into a public, non-proprietary book directory, a People’s Card Catalog? A web page for every book, perhaps in wiki format, wtih detailed bibliographic profiles, history, links, citation indices, social tools, visualizations, and ideally a smart graphical interface for browsing it. In a network of books, each title ought to have a stable node to which resources can be attached and from which discussions can branch. So far Google is leading the way in building this modern bibliographic system, and stands to turn the card catalogue of the future into a major advertising cash nexus. Let them do it. But couldn’t we build something better?

Category Archives: google_book_search

google library dominoes

Princeton is the latest university to partner up with the Google library project, signing an agreement to have 1 million public domain books scanned over the next six years. Over at ALA Techsource Tom Peters voices the growing unease among librarians worried about the long-term implications of commercial enclosure of the world’s leading research libraries.

unbound – google publishing conference at NYPL

Interesting bit of media industry theater here. I’m here in the New York Public Library, one of the city’s great temples to the book, where Google has assembled representatives of the book business to undergo a kind of group massage. A pep talk for a timorous publishing industry that has only barely dipped its toes in the digital marketplace and can’t decide whether to regard Google as savior or executioner. The speaker roster is a mix of leading academic and trade publishers and diplomatic envoys from the techno-elite. Chris Anderson, Cory Doctorow, Seth Godin, Tim O’Reilly have all spoken. The 800lb. elephant in the room is of course the lawsuits brought against Google (still in the discovery phase) by the Association of American Publishers and the Authors’ Guild for their library digitization program. Doctorow and O’Reilly broached it briefly and you could feel the pulse in the room quicken. Doctorow: “We’re a cabal come over from the west coast to tell you you’re all wrong!” A ripple of laughter, acid-laced. A little while ago Michael Holdsworth of Cambridge University Press pointed to statistics that suggest that Book Search is driving up their sales… Some grumble that the publishers’ panel was a little too hand-picked.

Google’s tactic here seems simultaneously to be to reassure the publishers while instilling an undercurrent of fear. Reassure them that releasing more of their books in a greater variety of forms will lead to more sales (true) — and frightening them that the technological train is speeding off without them (also true, though I say that without the ecstatic determinism of the Google folks. Jim Gerber, Google’s main liason to the publishing world, opened the conference with a love song to Moore’s Law and the gigapixel camera, explaining that we’re within a couple decades’ reach of having a handheld device that can store all the content ever produced in human history — as if this fact alone should drive the future of publishing). The event feels more like a workshop in web marketing than a serious discussion about the future of publishing. It’s hard to swallow all the marketing speak: “maximizing digital content capabilities,” “consolidation by market niche”; a lot of talk of “users” and “consumers,” but not a whole lot about readers. Publishers certainly have a lot of catching up to do in the area of online commerce, but barely anyone here is engaging with the bigger questions of what it means to be a publisher in the network era. O’Reilly sums up the publisher’s role as “spreading the knowledge of innovators.” This is more interesting and O’Reilly is undoubtedly doing more than almost any commercial publisher to rethink the reading experience. But most of the discussion here is about a culture industry that seems more concerned with salvaging the industry part of itself than with honestly rethinking the cultural part. The last speaker just wrapped up and it’s cocktail time. More thoughts tomorrow.

worth reading

In 2005, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, the President of the Bibliothè que Nationale (France’s equivalent of the Library of Congress) wrote one of the most trenchant critiques of Google’s intention to digitize millions of books from a number of major libraries. Jeanneney expanded on his original essay and this past October, The University of Chicago Press published a translation of Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge: A View from Europe. In this December’s D-Lib Magazine, there’s a superb precis and analysis of Jeanneney’s book by Dave Bearman.

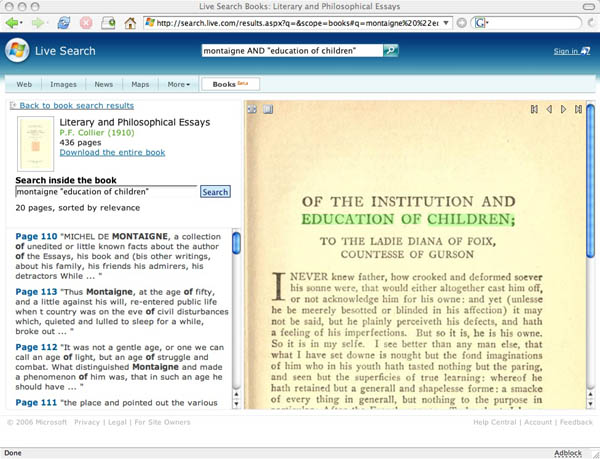

microsoft launches live search books

Windows Live Search Books, Microsoft’s answer to Google Book Search, is officially up and running and looks and feels pretty much the same as its nemesis. Being a Microsoft product, the interface is clunkier, and they have a bit of catching up to do in terms of navigation and search options. The one substantive difference is that Live Search is mostly limited to out-of-copyright books — i.e. pre-19231927 editions of public domain works. So the little they do have in there is fully accessible, with PDFs available for download. Like Google’s public domain books, however, the scans are of pretty poor quality, and not searchable. Readers point out that Microsoft, unlike Google, does in fact include a layer of low-quality but entirely searchable OCR text in its public domain downloads.

brewster kahle on the google book search “nightmare”

“Pretty much Google is trying to set themselves up as the only place to get to these materials; the only library; the only access. The idea of having only one company control the library of human knowledge is a nightmare.”

From a video interview with Elektrischer Reporter (click image to view).

(via Google Blogoscoped)

google makes slight improvements to book search interface

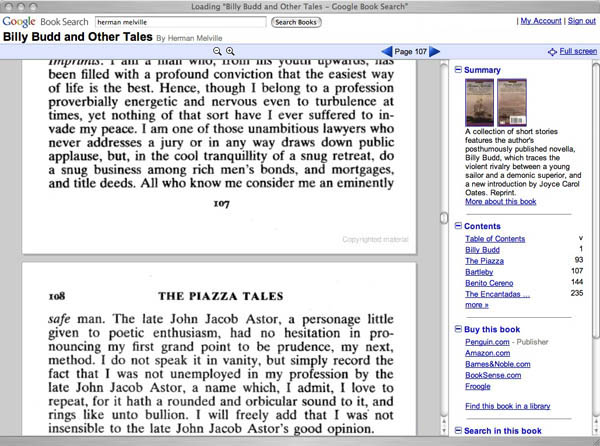

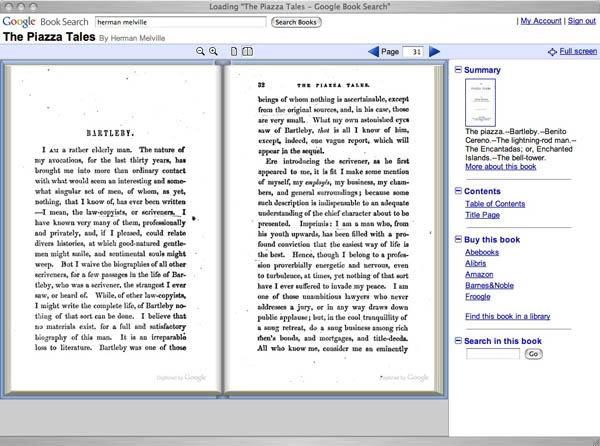

Google has added a few interface niceties to its Book Search book viewer. It now loads multiple pages at a time, giving readers the option of either scrolling down or paging through left to right. There’s also a full screen reading mode and a “more about this book” link taking you to a profile page with links to related titles plus references and citations from other books or from articles in Google Scholar. Also on the profile page is a searchable keyword cluster of high-incidence names or terms from the text.

Above is the in-copyright Signet Classic edition of Billy Budd and Other Tales by Melville, which contains only a limited preview of the text. You can also view the entire original 1856 edition of Piazza Tales as scanned from the Stanford Library. Public domain editions like this one can now be viewed with facing pages.

Still a conspicuous lack of any annotation or social reading tools.

microsoft steps up book digitization

Back in June, Microsoft struck deals with the University of California and the University of Toronto to scan titles from their nearly 50 million (combined) books into its Windows Live Book Search service. Today, the Guardian reports that they’ve forged a new alliance with Cornell and are going to step up their scanning efforts toward a launch of the search portal sometime toward the beginning of next year. Microsoft will focus on public domain works, but is also courting publishers to submit in-copyright books.

Making these books searchable online is a great thing, but I’m worried by the implications of big coprorations building proprietary databases of public domain works. At the very least, we’ll need some sort of federated book search engine that can leap the walls of these competing services, matching text queries to texts in Google, Microsoft and the Open Content Alliance (which to my understanding is mostly Microsoft anyway).

But more important, we should get to work with OCR scanners and start extracting the texts to build our own databases. Even when they make the files available, as Google is starting to do, they’re giving them to us not as fully functioning digital texts (searchable, remixable), but as strings of snapshots of the scanned pages. That’s because they’re trying to keep control of the cultural DNA scanned from these books — that’s the value added to their search service.

But the public domain ought to be a public trust, a cultural infrastructure that is free to all. In the absence of some competing not-for-profit effort, we should at least start thinking about how we as stakeholders can demand better access to these public domain works. Microsoft and Google are free to scan them, and it’s good that someone has finally kickstarted a serious digitization campaign. It’s our job to hold them accountable, and to make sure that the public domain doesn’t get redefined as the semi-public domain.

literary zeitgest, google-style

At the Frankfurt Book Fair this week, Google revealed a small batch of data concerning use patterns on Google Book Search: a list of the ten most searched titles from September 17 to 23. Google already does this sort of snapshotting for general web search with its “zeigeist” feature, a weekly, monthly or annual list of the most popular, or gaining, search queries for a given period — presented as a screengrab of the collective consciousness, or a slice of what John Battelle calls “the database of intentions.” The top ten book list is a very odd assortment, a mix of long tail eclecticism and current events:

Diversity and Evolutionary Biology of Tropical Flowers By Peter K. Endress

Merriam Webster’s Dictionary of Synonyms

Measuring and Controlling Interest Rate and Credit Risk By Frank J. Fabozzi, Steven V. Mann, Moorad Choudhry

Ultimate Healing: The Power of Compassion By Lama Zopa Rinpoche; Edited by Ailsa Cameron

The Holy Qur’an Translated by Abdullah Yusuf Ali

Peterson’s Study Abroad 2006

Hegemony Or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance By Noam Chomsky

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage

Perrine ‘s Literature: Structure, Sound, and Sense By Thomas R Arp, Greg Johnson

Build Your Own All-Terrain Robot By Brad Graham, Kathy McGowan

(reported in Reuters and InfoWorld)

google and the future of print

Veteran editor and publisher Jason Epstein, the man who first introduced paperbacks to American readers, discusses recent Google-related books (John Battelle, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, David Vise etc.) in the New York Review, and takes the opportunity to promote his own vision for the future of publishing. As if to reassure the Updikes of the world, Epstein insists that the “sparkling cloud of snippets” unleashed by Google’s mass digitization of libraries will, in combination with a radically decentralized print-on-demand infrastructure, guarantee a bright future for paper books:

[Google cofounder Larry] Page’s original conception for Google Book Search seems to have been that books, like the manuals he needed in high school, are data mines which users can search as they search the Web. But most books, unlike manuals, dictionaries, almanacs, cookbooks, scholarly journals, student trots, and so on, cannot be adequately represented by Googling such subjects as Achilles/wrath or Othello/jealousy or Ahab/whales. The Iliad, the plays of Shakespeare, Moby-Dick are themselves information to be read and pondered in their entirety. As digitization and its long tail adjust to the norms of human nature this misconception will cure itself as will the related error that books transmitted electronically will necessarily be read on electronic devices.

Epstein predicts that in the near future nearly all books will be located and accessed through a universal digital library (such as Google and its competitors are building), and, when desired, delivered directly to readers around the world — made to order, one at a time — through printing machines no bigger than a Xerox copier or ATM, which you’ll find at your local library or Kinkos, or maybe eventually in your home.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Epstein has founded a new company, OnDemand Books, to realize this vision, and earlier this year, they installed test versions of the new “Espresso Book Machine” (pictured) — capable of producing a trade paperback in ten minutes — at the World Bank in Washington and (with no small measure of symbolism) at the Library of Alexandria in Egypt.

Epstein is confident that, with a print publishing system as distributed and (nearly) instantaneous as the internet, the codex book will persist as the dominant reading mode far into the digital age.