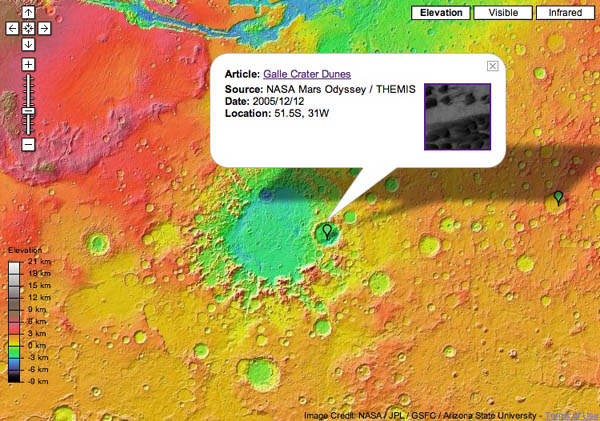

Apparently, this came out in March, but I ‘ve only just stumbled on it now. Google has a version of its maps program for the planet Mars, or at least the part of if explored and documented by the 2001 NASA Mars Odyssey mission. It’s quite spectacular, especially the psychedelic elevation view:

There’s also various info tied to specific coordinates on the map: location of dunes, craters, planes etc., as well as stories from the Odyssey mission, mostly descriptions of the Martian landscape. It would be fun to do an anthology of Mars-located science fiction with the table of contents mapped, or an edition of Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles. Though I suppose there’d a fair bit of retrofitting of the atlas to tales written out of pure fancy and not much knowledge of Martian geography (Marsography?). If nothing else, there’s the seeds of a great textbook here. Does the Google Maps API extend to Mars, or is it just an earth thing?

Category Archives: google

u.c. offers up stacks to google

Less than two months after reaching a deal with Microsoft, the University of California has agreed to let Google scan its vast holdings (over 34 million volumes) into the Book Search database. Google will undoubtedly dig deeper into the holdings of the ten-campus system’s 100-plus libraries than Microsoft, which is a member of the more copyright-cautious Open Content Alliance, and will focus primarily on books unambiguously in the public domain. The Google-UC alliance comes as major lawsuits against Google from the Authors Guild and Association of American Publishers are still in the evidence-gathering phase.

Meanwhile, across the drink, French publishing group La Martiniè re in June brought suit against Google for “counterfeiting and breach of intellectual property rights.” Pretty much the same claim as the American industry plaintiffs. Later that month, however, German publishing conglomerate WBG dropped a petition for a preliminary injunction against Google after a Hamburg court told them that they probably wouldn’t win. So what might the future hold? The European crystal ball is murky at best.

During this period of uncertainty, the OCA seems content to let Google be the legal lightning rod. If Google prevails, however, Microsoft and Yahoo will have a lot of catching up to do in stocking their book databases. But the two efforts may not be in such close competition as it would initially seem.

Google’s library initiative is an extremely bold commercial gambit. If it wins its cases, it stands to make a great deal of money, even after the tens of millions it is spending on the scanning and indexing the billions of pages, off a tiny commodity: the text snippet. But far from being the seed of a new literary remix culture, as Kevin Kelly would have us believe (and John Updike would have us lament), the snippet is simply an advertising hook for a vast ad network. Google’s not the Library of Babel, it’s the most sublimely sophisticated advertising company the world has ever seen (see this funny reflection on “snippet-dangling”). The OCA, on the other hand, is aimed at creating a legitimate online library, where books are not a means for profit, but an end in themselves.

Brewster Kahle, the founder and leader of the OCA, has a rather immodest aim: “to build the great library.” “That was the goal I set for myself 25 years ago,” he told The San Francisco Chronicle in a profile last year. “It is now technically possible to live up to the dream of the Library of Alexandria.”

So while Google’s venture may be more daring, more outrageous, more exhaustive, more — you name it –, the OCA may, in its slow, cautious, more idealistic way, be building the foundations of something far more important and useful. Plus, Kahle’s got the Bookmobile. How can you not love the Bookmobile?

harpercollins takes on online book browsing

In general, people in the US do not seem to be reading a lot of books, with one study citing that 80% of US families did not buy or read a book last year. People are finding their information in other ways. Therefore it is not surprising that HarpersCollins announced it “Browse Inside” feature, which to allows people to view selected pages from books by ten leading authors, including Michael Crichton and C.S. Lewis. They compare this feature with “Google Book Search” and Amazon’s “Search Inside.”

The feature is much closer to “Search Inside” than “Google Book Search.” Although Amazon.com has a nice feature “Surprise Me” which comes closer to replicating the experience of flipping randomly to a page in a book off the shelf. Of course “Google Book Search” actually lets you search the book and comes the closest to giving people the experiences of browsing through books in a physical store.

In the end, HarperCollins’ feature is more like a movie trailer. That is, readers get a selected pages to view that were pre-detereminded. This is nothing like the experience of randomly opening a book, or going to the index to make sure the book covers the exact information you need. The press release from HarperCollins states that they will be rolling out additional features and content for registered users soon. However, for now, without any unique features, it is unclear to me, why someone would go to the HarperCollins site to get a preview of only their books, rather than go to the Amazon and get previews across many more publishers.

This initiative is a small step in the correct direction. At the end of the day, it’s a marketing tool, and limits itself to that. Because they added links to various book sellers on the page, they can potentially reap the benefits of the long tail, by assisting readers to find the more obscure titles in their catalogue. However, their focus is still on selling the physical book. They specifically stated that they do not want to be become booksellers. (Although through their “Digital Media Cafe,” they are experimenting with selling digital content through their website.)

As readers increasingly want to interact with their media and text, a big question remains. Is Harper Collins and the publishing industry ready to release control they traditionally held and reinterpret their purpose? With POD, search engines, emergent communities, we are seeing the formation of new authors, filters, editors and curators. They are playing the roles that publishers once traditional filled. It will be interesting to see how far Harper Collins goes with these initiatives. For instance, Harper Collins also has intentions to start working with myspace and facebook to add links to books on their site. Are they prepared for negative commentary associated with those links? Are they ready to allow people to decide which books get attention?

If traditional publishers do not provide media (including text) in ways we are increasingly accustomed to receiving it, their relevance is at risk. We see them slowly trying to adapt to the shifting expectations and behaviors of people. However, in order to maintain that relevance, they need to deeply rethink what a publisher is today.

the myth of universal knowledge 2: hyper-nodes and one-way flows

My post a couple of weeks ago about Jean-Noël Jeanneney’s soon-to-be-released anti-Google polemic sparked a discussion here about the cultural trade deficit and the linguistic diversity (or lack thereof) of digital collections. Around that time, Rüdiger Wischenbart, a German journalist/consultant, made some insightful observations on precisely this issue in an inaugural address to the 2006 International Conference on the Digitisation of Cultural Heritage in Salzburg. His discussion is framed provocatively in terms of information flow, painting a picture of a kind of fluid dynamics of global culture, in which volume and directionality are the key indicators of power.

My post a couple of weeks ago about Jean-Noël Jeanneney’s soon-to-be-released anti-Google polemic sparked a discussion here about the cultural trade deficit and the linguistic diversity (or lack thereof) of digital collections. Around that time, Rüdiger Wischenbart, a German journalist/consultant, made some insightful observations on precisely this issue in an inaugural address to the 2006 International Conference on the Digitisation of Cultural Heritage in Salzburg. His discussion is framed provocatively in terms of information flow, painting a picture of a kind of fluid dynamics of global culture, in which volume and directionality are the key indicators of power.

First, he takes us on a quick tour of the print book trade, pointing out the various roadblocks and one-way streets that skew the global mind map. A cursory analysis reveals, not surprisingly, that the international publishing industry is locked in a one-way flow maximally favoring the West, and, moreover, that present digitization efforts, far from ushering in a utopia of cultural equality, are on track to replicate this.

…the market for knowledge is substantially controlled by the G7 nations, that is to say, the large economic powers (the USA, Canada, the larger European nations and Japan), while the rest of the world plays a subordinate role as purchaser.

Foreign language translation is the most obvious arena in which to observe the imbalance. We find that the translation of literature flows disproportionately downhill from Anglophone heights — the further from the peak, the harder it is for knowledge to climb out of its local niche. Wischenbart:

An already somewhat obsolete UNESCO statistic, one drawn from its World Culture Report of 2002, reckons that around one half of all translated books worldwide are based on English-language originals. And a recent assessment for France, which covers the year 2005, shows that 58 percent of all translations are from English originals. Traditionally, German and French originals account for an additional one quarter of the total. Yet only 3 percent of all translations, conversely, are from other languages into English.

…When it comes to book publishing, in short, the transfer of cultural knowledge consists of a network of one-way streets, detours, and barred routes.

…The central problem in this context is not the purported Americanization of knowledge or culture, but instead the vertical cascade of knowledge flows and cultural exports, characterized by a clear power hierarchy dominated by larger units in relation to smaller subordinated ones, as well as a scarcity of lateral connections.

Turning his attention to the digital landscape, Wischenbart sees the potential for “new forms of knowledge power,” but quickly sobers us up with a look at the way decentralized networks often still tend toward consolidation:

Previously, of course, large numbers of books have been accessible in large libraries, with older books imposing their contexts on each new release. The network of contents encompassing book knowledge is as old as the book itself. But direct access to the enormous and constantly growing abundance of information and contents via the new information and communication technologies shapes new knowledge landscapes and even allows new forms of knowledge power to emerge.

Theorists of networks like Albert-Laszlo Barabasi have demonstrated impressively how nodes of information do not form a balanced, level field. The more strongly they are linked, the more they tend to constitute just a few outstandingly prominent nodes where a substantial portion of the total information flow is bundled together. The result is the radical antithesis of visions of an egalitarian cyberspace.

He then trains his sights on the “long tail,” that egalitarian business meme propogated by Chris Anderson’s new book, which posits that the new information economy will be as kind, if not kinder, to small niche markets as to big blockbusters. Wischenbart is not so sure:

He then trains his sights on the “long tail,” that egalitarian business meme propogated by Chris Anderson’s new book, which posits that the new information economy will be as kind, if not kinder, to small niche markets as to big blockbusters. Wischenbart is not so sure:

…there exists a massive problem in both the structure and economics of cultural linkage and transfer, in the cultural networks existing beyond the powerful nodes, beyond the high peaks of the bestseller lists. To be sure, the diversity found below the elongated, flattened curve does constitute, in the aggregate, approximately one half of the total market. But despite this, individual authors, niche publishing houses, translators and intermediaries are barely compensated for their services. Of course, these multifarious works are produced, and they are sought out and consumed by their respective publics. But the “long tail” fails to gain a foothold in the economy of cultural markets, only to become – as in the 18th century – the province of the amateur. Such is the danger when our attention is drawn exclusively to dominant productions, and away from the less surveyable domains of cultural and knowledge associations.

John Cassidy states it more tidily in the latest New Yorker:

There’s another blind spot in Anderson’s analysis. The long tail has meant that online commerce is being dominated by just a few businesses — mega-sites that can house those long tails. Even as Anderson speaks of plentitude and proliferation, you’ll notice that he keeps returning for his examples to a handful of sites — iTunes, eBay, Amazon, Netflix, MySpace. The successful long-tail aggregators can pretty much be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Many have lamented the shift in publishing toward mega-conglomerates, homogenization and an unfortunate infatuation with blockbusters. Many among the lamenters look to the Internet, and hopeful paradigms like the long tail, to shake things back into diversity. But are the publishing conglomerates of the 20th century simply being replaced by the new Internet hyper-nodes of the 21st? Does Google open up more “lateral connections” than Bertelsmann, or does it simply re-aggregate and propogate the existing inequities? Wischenbart suspects the latter, and cautions those like Jeanneney who would seek to compete in the same mode:

If, when breaking into the digital knowledge society, European initiatives (for instance regarding the digitalization of books) develop positions designed to counteract the hegemonic status of a small number of monopolistic protagonists, then it cannot possibly suffice to set a corresponding European pendant alongside existing “hyper nodes” such as Amazon and Google. We have seen this already quite clearly with reference to the publishing market: the fact that so many globally leading houses are solidly based in Europe does nothing to correct the prevailing disequilibrium between cultures.

google and the myth of universal knowledge: a view from europe

I just came across the pre-pub materials for a book, due out this November from the University of Chicago Press, by Jean-Noël Jeanneney, president of the Bibliothè que Nationale de France and famous critic of the Google Library Project. You’ll remember that within months of Google’s announcement of partnership with a high-powered library quintet (Oxford, Harvard, Michigan, Stanford and the New York Public), Jeanneney issued a battle cry across Europe, warning that Google, far from creating a universal world library, would end up cementing Anglo-American cultural hegemony across the internet, eroding European cultural heritages through the insidious linguistic uniformity of its database. The alarm woke Jacques Chirac, who, in turn, lit a fire under all the nations of the EU, leading them to draw up plans for a European Digital Library. A digitization space race had begun between the private enterprises of the US and the public bureaucracies of Europe.

I just came across the pre-pub materials for a book, due out this November from the University of Chicago Press, by Jean-Noël Jeanneney, president of the Bibliothè que Nationale de France and famous critic of the Google Library Project. You’ll remember that within months of Google’s announcement of partnership with a high-powered library quintet (Oxford, Harvard, Michigan, Stanford and the New York Public), Jeanneney issued a battle cry across Europe, warning that Google, far from creating a universal world library, would end up cementing Anglo-American cultural hegemony across the internet, eroding European cultural heritages through the insidious linguistic uniformity of its database. The alarm woke Jacques Chirac, who, in turn, lit a fire under all the nations of the EU, leading them to draw up plans for a European Digital Library. A digitization space race had begun between the private enterprises of the US and the public bureaucracies of Europe.

Now Jeanneney has funneled his concerns into a 96-page treatise called Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge: a View from Europe. The original French version is pictured above. From U. Chicago:

Jeanneney argues that Google’s unsystematic digitization of books from a few partner libraries and its reliance on works written mostly in English constitute acts of selection that can only extend the dominance of American culture abroad. This danger is made evident by a Google book search the author discusses here–one run on Hugo, Cervantes, Dante, and Goethe that resulted in just one non-English edition, and a German translation of Hugo at that. An archive that can so easily slight the masters of European literature–and whose development is driven by commercial interests–cannot provide the foundation for a universal library.

Now I’m no big lover of Google, but there are a few problems with this critique, at least as summarized by the publisher. First of all, Google is just barely into its scanning efforts, so naturally, search results will often come up threadbare or poorly proportioned. But there’s more that complicates Jeanneney’s charges of cultural imperialism. Last October, when the copyright debate over Google’s ambitions was heating up, I received an informative comment on one of my posts from a reader at the Online Computer Library Center. They had recently completed a profile of the collections of the five Google partner libraries, and had found, among other things, that just under half of the books that could make their way into Google’s database are in English:

More than 430 languages were identified in the Google 5 combined collection. English-language materials represent slightly less than half of the books in this collection; German-, French-, and Spanish-language materials account for about a quarter of the remaining books, with the rest scattered over a wide variety of languages. At first sight this seems a strange result: the distribution between English and non-English books would be more weighted to the former in any one of the library collections. However, as the collections are brought together there is greater redundancy among the English books.

Still, the “driven by commercial interests” part of Jeanneney’s attack is important and on-target. I worry less about the dominance of any single language (I assume Google wants to get its scanners on all books in all tongues), and more about the distorting power of the market on the rankings and accessibility of future collections, not to mention the effect on the privacy of users, whose search profiles become company assets. France tends much further toward the enlightenment end of the cultural policy scale — witness what they (almost) achieved with their anti-DRM iTunes interoperability legislation. Can you imagine James Billington, of our own Library of Congress, asserting such leadership on the future of digital collections? LOC’s feeble World Digital Library effort is a mere afterthought to what Google and its commercial rivals are doing (they even receive private investment from Google). Most public debate in this country is also of the afterthought variety. The privatization of public knowledge plows ahead, and yet few complain. Good for Jeanneney and the French for piping up.

the least interesting conversation in the world continues

Much as I hate to dredge up Updike and his crusty rejoinder to Kevin Kelly’s “Scan this Book” at last month’s Book Expo, The New York Times has refused to let it die, re-printing his speech in the Sunday Book Review under the headline, “The End of Authorship.” We should all thank the Times for perpetuating this most uninteresting war of words about the publishing future. Here, once again, is Updike:

Books traditionally have edges: some are rough-cut, some are smooth-cut, and a few, at least at my extravagant publishing house, are even top-stained. In the electronic anthill, where are the edges? The book revolution, which, from the Renaissance on, taught men and women to cherish and cultivate their individuality, threatens to end in a sparkling cloud of snippets.

I was reading Christine Boese’s response to this (always an exhilarating antidote to the usual muck), where she wonders about Updike’s use of history:

The part of this that is the most peculiar to me is the invoking of the Renaissance. I’d characterize that period as a time of explosive artistic and intellectual growth unleashed largely by social unrest due to structural and technological changes.

….swung the tipping point against the entrenched power arteries of the Church and Aristocracy, toward the rising merchant class and new ways of thinking, learning, and making, the end result was that the “fruit basket upset” of turning the known world’s power structures upside down opened the way to new kinds of art and literature and science.

So I believe we are (or were) in a similar entrenched period like that now. Except that there is a similar revolution underway. It unsettles many people. Many are brittle and want to fight it. I’m no determinist. I don’t see it as an inevitability. It looks to me more like a shift in the prevailing winds. The wind does not deterministically affect all who are buffeted the same way. Some resist, some bend, some spread their wings and fly off to wherever the wind will take them, for good or ill.

Normally, I’d hope the leading edge of our best artists and writers would understand such a shift, would be excited to be present at the birth of a new Renaissance. So it puzzles me that John Updike is sounding so much like those entrenched powers of the First and Second Estate who faced the Enlightenment and wondered why anyone would want a mass-printed book when clearly monk-copied manuscripts from the scriptoria are so much better?!

I say it again, it’s a shame that Kelly, the uncritical commercialist, and Updike, the nostaligic elitist, have been the ones framing the public debate. For most of us, Google is neither the eclipse nor dawn of authorship, but just a single feature of a shifting landscape. Search is merely a tool, a means: the books themselves are the end. Yet, neither Google Book Search, which is simply an apparatus for extracting new profits off of the transmission and search of books, nor the present-day publishing industry, dominated as it is by mega-conglomerates with their penchant for blockbusters (our culture haunted by vast legions of the out-of-print), serves those ends very well. And yet these are the competing futures of the book: lonely forts and sparkling clouds. Or so we’re told.

microsoft enlists big libraries but won’t push copyright envelope

In a significant challenge to Google, Microsoft has struck deals with the University of California (all ten campuses) and the University of Toronto to incorporate their vast library collections – nearly 50 million books in all – into Windows Live Book Search. However, a majority of these books won’t be eligible for inclusion in MS’s database. As a member of the decidedly cautious Open Content Alliance, Windows Live will restrict its scanning operations to books either clearly in the public domain or expressly submitted by publishers, leaving out the huge percentage of volumes in those libraries (if it’s at all like the Google five, we’re talking 75%) that are in copyright but out of print. Despite my deep reservations about Google’s ascendancy, they deserve credit for taking a much bolder stand on fair use, working to repair a major market failure by rescuing works from copyright purgatory. Although uploading libraries into a commercial search enclosure is an ambiguous sort of rescue.

in publishers weekly…

We’ve got a column in the latest Publishers Weekly. An appeal to publishers to start thinking about books in a network context.

good discussion(s) of kevin kelly article

In the New York Times own book discussion forum, one rirutsky opines eloquently on the problems with Kelly’s punch-drunk corporate optimism:

…what I find particularly problematic is the way that Kelly’s “analysis”–as well as most of the discussion of it–omits any serious mention of what is actually at stake in the utopian scheme of a universal library (which Borges, by the way, does not promote, but debunks). It has little to do with enabling creativity, but rather, with enabling greater corporate profits. Kelly is actually most close to the mark when [he] characterizes the conflict over digital books as a conflict between two business models. Of course, one gets the impression from some of Kelly’s writings that for him business and creativity are more or less the same thing….

….A more serious consideration of these issues would move away from the “old” binary antagonisms that Kelly outlines (surely, these are a relic of a pre-digital age) and think seriously about how society at large is changed by digital technologies and techniques. Who has the right to copy or to make use of data and who does not? In a world of such vast informational clutter, doesn’t power accrue to those who can afford to advertise? It is worth remembering, too, that searching is not, after all, a value-free operation. Who ultimately will control the searching and indexing of digital information? Should the government–or private corporations–be allowed to data mine the searches that people make? In short, who benefits and who loses from these technological changes? Where, precisely, is power consolidated?

Kelly does not even begin to deal with these sorts of serious social issues.

And from a typically immense Slashdot thread (from highlights conveniently collected by Branko Collin at Teleread) — this comes back to the “book is reading you” question:

Will all these books and articles require we login to view them first? I think having every book, article, movie, song, etc available for use anytime is a great idea and important for society but I don’t want to have to login and leave a paper trail of everything I’m looking at.

And we have our own little thread going here.

if:book in library journal (and kevin kelly in n.y. times)

The Institute is on the cover of Library Journal this week! A big article called “The Social Life of Books,” which gives a good overview of the intersecting ideas and concerns that we mull over here daily. It all started, actually, with that little series of posts I wrote a few months back, “the book is reading you” (parts 3, 2 and 1), which pondered the darker implications of Google Book Search and commercial online publishing. The article is mostly an interview with me, but it covers ideas and subjects that we’ve been working through as a collective for the past year and a half. Wikipedia, Google, copyright, social software, networked books — most of our hobby horses are in there.

The Institute is on the cover of Library Journal this week! A big article called “The Social Life of Books,” which gives a good overview of the intersecting ideas and concerns that we mull over here daily. It all started, actually, with that little series of posts I wrote a few months back, “the book is reading you” (parts 3, 2 and 1), which pondered the darker implications of Google Book Search and commercial online publishing. The article is mostly an interview with me, but it covers ideas and subjects that we’ve been working through as a collective for the past year and a half. Wikipedia, Google, copyright, social software, networked books — most of our hobby horses are in there.

I also think the article serves as a nice complement (and in some ways counterpoint) to Kevin Kelly’s big article on books and search engines in yesterday’s New York Times Magazine. Kelly does an excellent job outlining the thorny intellectual property issues raised by Google Book Search and the internet in general. In particular, he gives a very lucid explanation of the copyright “orphan” issue, of which most readers of the Times are probably unaware. At least 75% of the books in contention in Google’s scanning effort are works that have been pretty much left for dead by the publishing industry: works (often out of print) whose copyright status is unclear, and for whom the rights holder is unknown, dead or otherwise prohibitively difficult to contact. Once publishers’ and authors’ groups sensed there might finally be a way to monetize these works, they mobilized a legal offensive.

Kelly argues convincingly that not only does Google have the right to make a transformative use of these works (scanning them into a searchable database), but that there is a moral imperative to do so, since these works will otherwise be left forever in the shadows. That the Times published such a progressive statement on copyright (and called it a manifesto no less) is to be applauded. That said, there are other things I felt were wanting in the article. First, at no point does Kelly question whether private companies such as Google ought to become the arbiter of all the world’s information. He seems pretty satisfied with this projected outcome.

And though the article serves as a great introduction to how search engines will revolutionize books, it doesn’t really delve into how books themselves — their form, their authorship, their content — might evolve. Interlinked, unbundled, tagged, woven into social networks — he goes into all that. But Kelly still conceives of something pretty much like a normal book (a linear construction, in relatively fixed form, made of pages) that, like Dylan at Newport in 1965, has gone electric. Our article in Library Journal goes further into the new networked life of books, intimating a profound re-jiggering of the relationship between authors and readers, and pointing to new networked modes of reading and writing in which a book is continually re-worked, re-combined and re-negotiated over time. Admittedly, these ideas have been developed further on if:book since I wrote the article a month and a half ago (when a blogger writes an article for a print magazine, there’s bound to be some temporal dissonance). There’s still a very active thread on the “defining the networked book” post which opens up many of the big questions, and I think serves well as a pre-published sequel to the LJ interview. We’d love to hear people’s thoughts on both the Kelly and the LJ pieces. Seems to make sense to discuss them in the same thread.