SlideShare is a new web application that lets you upload PowerPoint (.ppt and .pps) or OpenOffice (.odp) slideshows to the web for people to use and share. The site (which is in an invite-only beta right now, though accounts are granted within minutes of a request) feels a lot like the now-merged Google Video and YouTube. Slideshows come up with a unique url, copy-and-paste embed code for bloggers, tags, a comment stream and links to related shows. Clicking a “full” button on the viewer controls enlarges the slideshow to fill up most of the screen. Here’s one I found humorously diagramming soccer strategies from various national teams:

Another resemblance to Google Video and YouTube: SlideShare rides the tidal wave of Flash-based applications that has swept through the web over the past few years. By achieving near-ubiquity with its plugin, Flash has become the gel capsule that makes rich media content easy to swallow across platform and browser (there’s a reason that the web video explosion happened when it did, the way it did). But in a sneaky way, this has changed the nature of our web browsers, transforming them into something that more resembles a highly customizable TV set. And by this I mean to point out that Flash inhibits the creative reuse of the materials being delivered since Flash-wrapped video (or slideshows) can’t, to my knowledge, be easily broken apart and remixed.

Where once the “view source” ethic of web browsers reigned, allowing you to retrieve the underlying html code of any page and repurpose all or parts of it on your own site, the web is becoming a network of congealed packages — bite-sized broadcast units that, while nearly effortless to disseminate through linking and embedding, are much less easily reworked or repurposed (unless the source files are made available). The proliferation of rich media and dynamic interfaces across the web is no doubt exciting, but it’s worth considering this darker side.

Category Archives: google

literary zeitgest, google-style

At the Frankfurt Book Fair this week, Google revealed a small batch of data concerning use patterns on Google Book Search: a list of the ten most searched titles from September 17 to 23. Google already does this sort of snapshotting for general web search with its “zeigeist” feature, a weekly, monthly or annual list of the most popular, or gaining, search queries for a given period — presented as a screengrab of the collective consciousness, or a slice of what John Battelle calls “the database of intentions.” The top ten book list is a very odd assortment, a mix of long tail eclecticism and current events:

Diversity and Evolutionary Biology of Tropical Flowers By Peter K. Endress

Merriam Webster’s Dictionary of Synonyms

Measuring and Controlling Interest Rate and Credit Risk By Frank J. Fabozzi, Steven V. Mann, Moorad Choudhry

Ultimate Healing: The Power of Compassion By Lama Zopa Rinpoche; Edited by Ailsa Cameron

The Holy Qur’an Translated by Abdullah Yusuf Ali

Peterson’s Study Abroad 2006

Hegemony Or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance By Noam Chomsky

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage

Perrine ‘s Literature: Structure, Sound, and Sense By Thomas R Arp, Greg Johnson

Build Your Own All-Terrain Robot By Brad Graham, Kathy McGowan

(reported in Reuters and InfoWorld)

google and the future of print

Veteran editor and publisher Jason Epstein, the man who first introduced paperbacks to American readers, discusses recent Google-related books (John Battelle, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, David Vise etc.) in the New York Review, and takes the opportunity to promote his own vision for the future of publishing. As if to reassure the Updikes of the world, Epstein insists that the “sparkling cloud of snippets” unleashed by Google’s mass digitization of libraries will, in combination with a radically decentralized print-on-demand infrastructure, guarantee a bright future for paper books:

[Google cofounder Larry] Page’s original conception for Google Book Search seems to have been that books, like the manuals he needed in high school, are data mines which users can search as they search the Web. But most books, unlike manuals, dictionaries, almanacs, cookbooks, scholarly journals, student trots, and so on, cannot be adequately represented by Googling such subjects as Achilles/wrath or Othello/jealousy or Ahab/whales. The Iliad, the plays of Shakespeare, Moby-Dick are themselves information to be read and pondered in their entirety. As digitization and its long tail adjust to the norms of human nature this misconception will cure itself as will the related error that books transmitted electronically will necessarily be read on electronic devices.

Epstein predicts that in the near future nearly all books will be located and accessed through a universal digital library (such as Google and its competitors are building), and, when desired, delivered directly to readers around the world — made to order, one at a time — through printing machines no bigger than a Xerox copier or ATM, which you’ll find at your local library or Kinkos, or maybe eventually in your home.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Epstein has founded a new company, OnDemand Books, to realize this vision, and earlier this year, they installed test versions of the new “Espresso Book Machine” (pictured) — capable of producing a trade paperback in ten minutes — at the World Bank in Washington and (with no small measure of symbolism) at the Library of Alexandria in Egypt.

Epstein is confident that, with a print publishing system as distributed and (nearly) instantaneous as the internet, the codex book will persist as the dominant reading mode far into the digital age.

google to scan spanish library books

The Complutense University of Madrid is the latest library to join Google’s digitization project, offering public domain works from its collection of more than 3 million volumes. Most of the books to be scanned will be in Spanish, as well as other European languages (read more in Reuters , or at the Biblioteca Complutense (en espagnol)). I also recently came across news that Google is seeking commercial partnerships with english-language publishers in India.

The Complutense University of Madrid is the latest library to join Google’s digitization project, offering public domain works from its collection of more than 3 million volumes. Most of the books to be scanned will be in Spanish, as well as other European languages (read more in Reuters , or at the Biblioteca Complutense (en espagnol)). I also recently came across news that Google is seeking commercial partnerships with english-language publishers in India.

While celebrating the fact that these books will be online (and presumably downloadable in Google’s shoddy, unsearchable PDF editions), we should consider some of the dynamics underlying the migration of the world’s libraries and publishing houses to the supposedly placeless place we inhabit, the web.

No doubt, Google’s scanners are aquiring an increasingly global reach, but digitization is a double-edged process. Think about the scanner. A photographic technology, it captures images and freezes states. What Google is doing is essentially photographing the world’s libraries and preparing the ultimate slideshow of human knowledge, the sequence and combination of the slides to be determined each time by the queries of each reader.

But perhaps Google’s scanners, in their dutifully accurate way, are in effect cloning existing arrangements of knowledge, preserving cultural trade deficits, and reinforcing the flow of knowledge power — all things we should be questioning at a time when new technologies have the potential to jigger old equations.

With Complutense on board, we see a familiar pyramid taking shape. Spanish takes its place below English in the global language hierarchy. Others will soon follow, completing this facsimile of the existing order.

google launches archival news search

Today Google unveiled a major extension of its news search service, expanding into periodical archives that stretch back to the mid-18th century. Most of the articles are pay downloads, or pay-per-view, and are offered by Google through licensing agreements with newspapers and existing document retrieval services including The New York Times Co., The Washington Post Co., The Wall Street Journal, Reed Elsevier, LexisNexis and Factiva. Google won’t actually host content or handle payments, it simply presents items with titles, brief excerpts and ordering information. Google also crawls free archives already on the web and mixes these in, and (a nice touch) links all search results to “related web pages,” plugging keywords into a general web search. Google won’t run adds in this service, at least for now. More coverage here and here.

This is a fine service, but it only underscores the need for a non-commercial alternative. Much of the material here is public domain, but is provided through commercial services. Google simply adds a new web-integrated layer. Anyone who believes that the public domain ought to be fully accessible to all should be thinking bigger than Google.

google flirts with image tagging

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

I played a few rounds but quickly grew tired of the bland consensus that the game encourages. Matches tend to be banal, basic descriptors, while anything tricky usually results in a pass. In other words, all the pleasure of folksonomies — splicing one’s own idiosyncratic sense of things with the usually staid task of classification — is removed here. I don’t see why they don’t open the database up to much broader tagging. Integrate it with the image search and harvest a bigger crop of metadata.

Right now, it’s more like Tom Sawyer tricking the other boys into whitewashing the fence. Only, I don’t think many will fall for this one because there’s no real incentive to participation beyond a halfhearted points system. For every matched tag, you and your partner score points, which accumulate in your Google account the more you play. As far as I can tell, though, points don’t actually earn you anything apart from a shot at ranking in the top five labelers, which Google lists at the end of each game. Whitewash, anyone?

In some ways, this reminded me of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an “artificial artificial intelligence” service where anyone can take a stab at various HIT’s (human intelligence tasks) that other users have posted. Tasks include anything from checking business hours on restaurant web sites against info in an online directory, to transcribing podcasts (there are a lot of these). “Typically these tasks are extraordinarily difficult for computers, but simple for humans to answer,” the site explains. In contrast to the Google image game, with the Mechanical Turk, you can actually get paid. Fees per HIT range from a single penny to several dollars.

I’m curious to see whether Google goes further with tagging. Flickr has fostered the creation of a sprawling user-generated taxonomy for its millions of images, but the incentives to tagging there are strong and inextricably tied to users’ personal investment in the production and sharing of images, and the building of community. Amazon, for its part, throws money into the mix, which (however modest the sums at stake) makes Mechanical Turk an intriguing, and possibly entertaining, business experiment, not to mention a place to make a few extra bucks. Google’s experiment offers neither, so it’s not clear to me why people should invest.

google offers public domain downloads

Google announced today that it has made free downloadable PDFs available for many of the public domain books in its database. This is a good thing, but there are several problems with how they’ve done it. The main thing is that these PDFs aren’t actually text, they’re simply strings of images from the scanned library books. As a result, you can’t select and copy text, nor can you search the document, unless, of course, you do it online in Google. So while public access to these books is a big win, Google still has us locked into the system if we want to take advantage of these books as digital texts.

A small note about the public domain. Editions are key. A large number of books scanned so far by Google have contents in the public domain, but are in editions published after the cut-off (I think we’re talking 1923 for most books). Take this 2003 Signet Classic edition of the Darwin’s The Origin of Species. Clearly, a public domain text, but the book is in “limited preview” mode on Google because the edition contains an introduction written in 1958. Copyright experts out there: is it just this that makes the book off limits? Or is the whole edition somehow copyrighted?

Other responses from Teleread and Planet PDF, which has some detailed suggestions on how Google could improve this service.

showtiming our libraries

Google’s contract with the University of California to digitize library holdings was made public today after pressure from The Chronicle of Higher Education and others. The Chronicle discusses some of the key points in the agreement, including the astonishing fact that Google plans to scan as many as 3,000 titles per day, and its commitment, at UC’s insistence, to always make public domain texts freely and wholly available through its web services.

Google’s contract with the University of California to digitize library holdings was made public today after pressure from The Chronicle of Higher Education and others. The Chronicle discusses some of the key points in the agreement, including the astonishing fact that Google plans to scan as many as 3,000 titles per day, and its commitment, at UC’s insistence, to always make public domain texts freely and wholly available through its web services.

But there are darker revelations as well, and Jeff Ubois, a TV-film archivist and research associate at Berkeley’s School of Information Management and Systems, hones in on some of these on his blog. Around the time that the Google-UC deal was first announced, Ubois compared it to Showtime’s now-infamous compact with the Smithsonian, which caused a ripple of outrage this past April. That deal, the details of which are secret, basically gives Showtime exclusive access to the Smithsonian’s film and video archive for the next 30 years.

The parallels to the Google library project are many. Four of the six partner libraries, like the Smithsonian, are publicly funded institutions. And all the agreements, with the exception of U. Michigan, and now UC, are non-disclosure. Brewster Kahle, leader of the rival Open Content Alliance, put the problem clearly and succinctly in a quote in today’s Chronicle piece:

We want a public library system in the digital age, but what we are getting is a private library system controlled by a single corporation.

He was referring specifically to sections of this latest contract that greatly limit UC’s use of Google copies and would bar them from pooling them in cooperative library systems. I vocalized these concerns rather forcefully in my post yesterday, and may have gotten a couple of details wrong, or slightly overstated the point about librarians ceding their authority to Google’s algorithms (some of the pushback in comments and on other blogs has been very helpful). But the basic points still stand, and the revelations today from the UC contract serve to underscore that. This ought to galvanize librarians, educators and the general public to ask tougher questions about what Google and its partners are doing. Of course, all these points could be rendered moot by one or two bad decisions from the courts.

librarians, hold google accountable

I’m quite disappointed by this op-ed on Google’s library intiative in Tuesday’s Washington Post. It comes from Richard Ekman, president of the Council of Independent Colleges, which represents 570 independent colleges and universities in the US (and a few abroad). Generally, these are mid-tier schools — not the elite powerhouses Google has partnered with in its digitization efforts — and so, being neither a publisher, nor a direct representative of one of the cooperating libraries, I expected Ekman might take a more measured approach to this issue, which usually elicits either ecstatic support or vociferous opposition. Alas, no.

To the opposition, namely, the publishing industry, Ekman offers the usual rationale: Google, by digitizing the collections of six of the english-speaking world’s leading libraries (and, presumably, more are to follow) is doing humanity a great service, while still fundamentally respecting copyrights — so let’s not stand in its way. With Google, however, and with his own peers in education, he is less exacting.

The nation’s colleges and universities should support Google’s controversial project to digitize great libraries and offer books online. It has the potential to do a lot of good for higher education in this country.

Now, I’ve poked around a bit and located the agreement between Google and the U. of Michigan (freely available online), which affords a keyhole view onto these grand bargains. Basically, Google makes scans of U. of M.’s books, giving them images and optical character recognition files (the texts gleaned from the scans) for use within their library system, keeping the same for its own web services. In other words, both sides get a copy, both sides win.

If you’re not Michigan or Google, though, the benefits are less clear. Sure, it’s great that books now come up in web searches, and there’s plenty of good browsing to be done (and the public domain texts, available in full, are a real asset). But we’re in trouble if this is the research tool that is to replace, by force of market and by force of users’ habits, online library catalogues. That’s because no sane librarian would outsource their profession to an unaccountable private entity that refuses to disclose the workings of its system — in other words, how does Google’s book algorithm work, how are the search results ranked? And yet so many librarians are behind this plan. Am I to conclude that they’ve all gone insane? Or are they just so anxious about the pace of technological change, driven to distraction by fears of obsolescence and diminishing reach, that they are willing to throw their support uncritically behind the company, who, like a frontier huckster, promises miracle cures and grand visions of universal knowledge?

We may be resigned to the steady takeover of college bookstores around the country by Barnes and Noble, but how do we feel about a Barnes and Noble-like entity taking over our library systems? Because that is essentially what is happening. We ought to consider the Google library pact as the latest chapter in a recent history of consolidation and conglomeratization in publishing, which, for the past few decades (probably longer, I need to look into this further) has been creeping insidiously into our institutions of higher learning. When Google struck its latest deal with the University of California, and its more than 100 libraries, it made headlines in the technology and education sections of newspapers, but it might just as well have appeared in the business pages under mergers and acquisitions.

So what? you say. Why shouldn’t leaders in technology and education seek each other out and forge mutually beneficial relationships, relationships that might yield substantial benefits for large numbers of people? Okay. But we have to consider how these deals among titans will remap the information landscape for the rest of us. There is a prevailing attitude today, evidenced by the simplistic public debate around this issue, that one must accept technological advances on the terms set by those making the advances. To question Google (and its collaborators) means being labeled reactionary, a dinosaur, or technophobic. But this is silly. Criticizing Google does not mean I am against digital libraries. To the contrary, I am wholeheartedly in favor of digital libraries, just the right kind of digital libraries.

What good is Google’s project if it does little more than enhance the world’s elite libraries and give Google the competitive edge in the search wars (not to mention positioning them in future ebook and print-on-demand markets)? Not just our little institute, but larger interest groups like the CIC ought to be voices of caution and moderation, celebrating these technological breakthroughs, but at the same time demanding that Google Book Search be more than a cushy quid pro quo between the powerful, with trickle-down benefits that are dubious at best. They should demand commitments from the big libraries to spread the digital wealth through cooperative web services, and from Google to abide by certain standards in its own web services, so that smaller librarians in smaller ponds (and the users they represent) can trust these fantastic and seductive new resources. But Ekman, who represents 570 of these smaller ponds, doesn’t raise any of these questions. He just joins the chorus of approval.

What’s frustrating is that the partner libraries themselves are in the best position to make demands. After all, they have the books that Google wants, so they could easily set more stringent guidelines for how these resources are to be redeployed. But why should they be so magnanimous? Why should they demand that the wealth be shared among all institutions? If every student can access Harvard’s books with the click of a mouse, than what makes Harvard Harvard? Or Stanford Stanford?

Enlightened self-interest goes only so far. And so I repeat, that’s why people like Ekman, and organizations like the CIC, should be applying pressure to the Harvards and Stanfords, as should organizations like the Digital Library Federation, which the Michigan-Google contract mentions as a possible beneficiary, through “cooperative web services,” of the Google scanning. As stipulated in that section (4.4.2), however, any sharing with the DLF is left to Michigan’s “sole discretion.” Here, then, is a pressure point! And I’m sure there are others that a more skilled reader of such documents could locate. But a quick Google search (acceptable levels of irony) of “Digital Library Federation AND Google” yields nothing that even hints at any negotiations to this effect. Please, someone set me straight, I would love to be proved wrong.

Google, a private company, is in the process of annexing a major province of public knowledge, and we are allowing it to do so unchallenged. To call the publishers’ legal challenge a real challenge, is to misidentify what really is at stake. Years from now, when Google, or something like it, exerts unimaginable influence over every aspect of our informated lives, we might look back on these skirmishes as the fatal turning point. So that’s why I turn to the librarians. Raise a ruckus.

UPDATE (8/25): The University of California-Google contract has just been released. See my post on this.

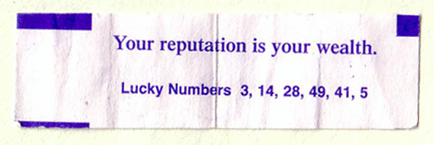

the wisdom of fortune cookies: “your reputation is your wealth”

Over cold jasmine tea and quartered oranges in Chinatown, I got this little gem of a fortune. I chuckled at its relevance to our work at the institute. With the rise of self publishing (blogs, wikis, and POD), being google searchable, and content being freely given away, I wonder what our readers think about reputations being our wealth. Is this truth, nothing new, tom foolery, or just a fad? Has the concept of “reputation” changed? Have you and your work felt an effect as well? If so, how? I’m looking forward to hearing your thoughts.