I spend a lot of time looking for specific resources on the web. That means sifting through Google search results and following links that seem promising. A semi-interesting link may take me to an article with another semi-interesting link; that link takes me to another, and so on. As I progress, the articles become more thinly related to the topic, but I pursue them anyway, hoping they will lead me on a trajectory I hadn’t thought of, to a great idea that I couldn’t have anticipated.

I spend a lot of time looking for specific resources on the web. That means sifting through Google search results and following links that seem promising. A semi-interesting link may take me to an article with another semi-interesting link; that link takes me to another, and so on. As I progress, the articles become more thinly related to the topic, but I pursue them anyway, hoping they will lead me on a trajectory I hadn’t thought of, to a great idea that I couldn’t have anticipated.

During the whole process, however, I can’t shake the unpleasant sensation that I am not the master of my own destiny. I come out of a Google session with a wrung-out feeling, like I’ve just been lead along a path that was not entirely of my own choosing, marching behind an army of web searchers carving networked pathways into the information landscape, but not necessarily finding that unique morsel that will knit my ideas together. Lee Bryant explains this phenomenon as entaglement in the complex systems addressed by complexity theory. “Complexity theory,” says Bryant, “shows us that from the seeds of such small inter-connected actions, large trees of system behaviour can grow. These physical phenomena are reflected online as well, where the emergence of the Wiki movement and the growing cult of Google both display a simple form of collective intelligence.” He gives us this metaphor to consider:

The classic pop-science example that illustrates the point is the way in which ants forage for food. Ants display a kind of collective intelligence (described by some as a “hive mind” ) that is based on apparently dumb rules, repetitively followed by thousands of individual insects. Each ant forages for food in an apparently random manner, but when it finds food it marks a pheromone trail back to its colony. Trails fade over time, but positive feedback means that well-travelled paths will attract more and more ants until the particular food source is exhausted. The system works because there are enough ants each following the same rules to ensure comprehensive coverage of any given area.

The fact that my participation in the web, even at the browsing level, means that I will be drawn, unavoidably, into the group effort evokes a mixed response. My independent artistic sensibility hates anything that erases the individual voice and immerses me in a placid groupthink. But my social human sensibility sincerely wants to know what everyone else is doing; it makes me want to dive in, pitch in, follow along, and celebrate the complex social web we are weaving.

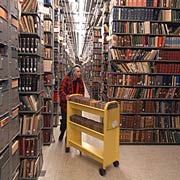

The recent buzz surrounding Google’s library intitiative has everyone talking about the future of research, which inevitably raises the question: how will the digitization of library collections change the role of the librarian? I would guess that, far from becoming obsolete, their role will in fact be elevated in importance, if not necessarily in status. They could very well come to be our indispensible guides through the labyrinth – if perhaps invisible, engineering behind the digital walls.

The recent buzz surrounding Google’s library intitiative has everyone talking about the future of research, which inevitably raises the question: how will the digitization of library collections change the role of the librarian? I would guess that, far from becoming obsolete, their role will in fact be elevated in importance, if not necessarily in status. They could very well come to be our indispensible guides through the labyrinth – if perhaps invisible, engineering behind the digital walls.