Wired has a piece today about authors who are in favor of Google’s plans to digitize millions of books and make them searchable online. Most seem to agree that obscurity is a writer’s greatest enemy, and that the exposure afforded by Google’s program far outweighs any intellectual property concerns. Sometimes to get more you have to give a little.

The article also mentions the institute.

Category Archives: google

debating google print

The Washington Post has run a pair of op-eds, one from each side of the Google Print dispute. Neither says anything particularly new. Moreover, they enforce the perception that there can be only two positions on the subject — an endemic problem in newspaper opinion pages with their addiction to binaries, where two cardboard boxers are allotted their space to throw a persuasive punch. So you’re either for Google or against it? That’s awfully close to you’re either for technology — for progress — or against it. Unfortunately, like technology’s impact, the Google book-scanning project is a little trickier to figure out, and a more nuanced conversation is probably in order.

The first piece, “Riches We Must Share…”, is submitted in support of Google by University of Michigan President Sue Coleman (a partner in the Google library project). She argues that opening up the elitist vaults of the world’s great (english) research libraries will constitute a democratic revolution. “We believe the result can be a widening of human conversation comparable to the emergence of mass literacy itself.” She goes on to deliver some boilerplate about the “Net Generation” — too impatient to look for books unless they’re online etc. etc. (great to see a major university president being led by the students instead of leading herself).

Coleman then devotes a couple of paragraphs to the copyright question, failing to tackle any of its controversial elements:

Universities are no strangers to the responsible management of complex copyright, permission and security issues; we deal with them every day in our classrooms, libraries, laboratories and performance halls. We will continue to work within the current criteria for fair use as we move ahead with digitization.

The problem is, Google is stretching the current criteria of fair use, possibly to the breaking point. Coleman does not acknowledge or address this. She does, however, remind the plaintiffs that copyright is not only about the owners:

The protections of copyright are designed to balance the rights of the creator with the rights of the public. At its core is the most important principle of all: to facilitate the sharing of knowledge, not to stifle such exchange.

All in all a rather bland statement in support of open access. It fails to weigh in on the fair use question — something about which the academy should have a few things to say — and does not indicate any larger concern about what Google might do with its books database down the road.

The opposing view, “…But Not at Writers’ Expense”, comes from Nick Taylor, writer, and president of the Authors’ Guild (which sued Google last month). Taylor asserts that mega-rich Google is tramping on the dignity of working writers. But a couple of paragraphs in, he gets a little mixed up about contemporary publishing:

Except for a few big-name authors, publishers roll the dice and hope that a book’s sales will return their investment. Because of this, readers have a wealth of wonderful books to choose from.

A dubious assessment, since publishing conglomerates are not exactly enthusiastic dice rollers. I would counter that risk-averse corporate publishing has steadily shrunk the number of available titles, counting on a handful of blockbusters to drive the market. Taylor goes on to defend not just the publishing status quo, but the legal one:

Now that the Authors Guild has objected, in the form of a lawsuit, to Google’s appropriation of our books, we’re getting heat for standing in the way of progress, again for thoughtlessly wanting to be paid. It’s been tradition in this country to believe in property rights. When did we decide that socialism was the way to run the Internet?

First of all, it’s funny to think of the huge corporations that dominate the web as socialist. Second, this talk about being paid for appropriating books for a search database is revealing of the two totally different worldviews that are at odds in this struggle. The authors say that any use of their book requires a payment. Google sees including the books in the database as a kind of payment in itself. No one with a web page expects Google to pay them for indexing their site. They are grateful that they do! Otherwise, they are totally invisible. This is the unspoken compact that underpins web search. Google assumed the same would apply with books. Taylor says not so fast.

Here’s Taylor on fair use:

Google contends that the portions of books it will make available to searchers amount to “fair use,” the provision under copyright that allows limited use of protected works without seeking permission. That makes a private company, which is profiting from the access it provides, the arbiter of a legal concept it has no right to interpret. And they’re scanning the entire books, with who knows what result in the future.

Actually, Google is not doing all the interpreting. There is a legal precedent for Google’s reading of fair use established in the 2003 9th Circuit Court decision Kelly v. Arriba Soft. In the case, Kelly, a photographer, sued Arriba Soft, an online image search system, for indexing several of his photographs in their database. Kelly believed that his intellectual property had been stolen, but the court ruled that Arriba’s indexing of thumbnail-sized copies of images (which always linked to their source sites) was fair use: “Arriba’s use of the images serves a different function than Kelly’s use – improving access to information on the internet versus artistic expression.” Still, Taylor’s “with who knows what result in the future” concern is valid.

So on the one hand we have many writers and most publishers trying to defend their architecture of revenue (or, as Taylor would have it, their dignity). But I can’t imagine how Google Print would really be damaging that architecture, at least not in the foreseeable future. Rather it leverages it by placing it within the frame of another architecture: web search. The irony for the authors is that the current architecture doesn’t seem to be serving them terribly well. With print-on-demand gaining in quality and legitimacy, online book search could totally re-define what is an acceptable risk to publishers, and maybe more non-blockbuster authors would get published.

On the other hand we have the universities and libraries participating in Google’s program, delivering the good news of accessibility. But they are not sufficiently questioning what Google might do with its database down the road, or the implications of a private technology company becoming the principal gatekeeper of the world’s corpus.

If only this debate could be framed in a subtler way, rather than the for-Google-or-against-it paradigm we have now. I’m cautiously optimistic about the effect of having books searchable on the web. And I tend to believe it will be beneficial to authors and publishers. But I have other, deep reservations about the direction in which Google is heading, and feel that a number of things could go wrong. We think the cencorship of the marketplace is bad now in the age of publishing conglomerates. What if one company has total control of everything? And is keeping track of every book, every page, that you read. And is reading you while you read, throwing ads into your peripheral vision. I’m curious to hear from readers what they feel could be the hazards of Google Print.

google is sued… again

This time by publishers. Penguin Group USA, McGraw-Hill, Pearson Education, Simon & Schuster and John Wiley & Sons. The gripe is the same as with the Authors’ Guild, which filed suit last month alleging “massive copyright infringement.” Publishers fear a dangerous precedent is set by Google’s scanning of books to construct what amounts to a giant card catalogue on the web. Google claims “fair use” (see rationale), again pointing out that for copyrighted works only tiny “snippets” of text are displayed around keywords (though perhaps this is not yet fully in effect – I was searching around in this book and was able to look at quite a lot).

Google calls the publishers’ suit “near-sighted.” And it probably is. The benefit to readers and researchers will be tremendous, as will (Google is eager to point out) the exposure for authors and publishers. But Google Print is undoubtedly an earth-shaking program. Look at the reaction in Europe, where alarm bells rung by France warned of cultural imperialism, an english-drenched web. Heads of state and culture convened and initial plans for a European digital library have been drawn up.

What the transatlantic flap makes clear is that Google’s book scanning touches a deep nerve, and the argument over intellectual property, signficant though it is, distracts from a more profound human anxiety — an anxiety about the form of culture and the shape of thoughts. If we try to grope back through the millennia, we can find find an analogy in the invention of writing.

The shift from oral to written language froze speech into stable strings that could be transmitted and stored over distance and time. This change not only affected the modes of communication, it dramatically refigured the cognitive makeup of human beings (as McLuhan, Ong and others have described). We are currently going through another such shift. The digital takes the freezing medium of text and throws it back into fluidity. Like the melting of polar ice caps, it unsettles equilibriums, changes weather patterns. It is a lot to adjust to, and we wonder if our great-great-grandchildren will literally think differently from us.

But in spite of this disorienting new fluidity, we still have print, we still have the book. And actually, Google Print in many ways affirms this since its search returns will point to print retailers and brick-and-mortar libraries. Yet the fact remains that the canon is being scanned, with implications we can’t fully perceive, and future uses we can’t fully predict, and so it is understandable that many are unnerved. The ice is really beginning to melt.

In Phaedrus, Plato expresses a similar anxiety about the invention of writing. He tells the tale of Theuth, an Egyptian deity who goes around spreading the new technology, and one day encounters a skeptic in King Thamus:

…you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a power opposite to that which they in fact possess. For this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it; they will not exercise their memories, but, trusting in external, foreign marks, they will not bring things to remembrance from within themselves. You have discovered a remedy not for memory, but for reminding. You offer your students the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom. They will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.

As I type, I’m exhibiting wisdom without the reality. I’ve read Plato, but nowhere near exhaustively. Yet I can slash and weave texts on the web in seconds, throw together a blog entry and send it screeching into the commons. And with Google Print I can get the quote I need and let the rest of the book rot behind the security fence. This fluidity is dangerous because it makes connections so easy. Do we know what we are connecting?

google expands book-scanning project to europe

This week Google will be paying a visit to the Frankfurt Book Fair to talk with European publishers and chief librarians (including arch nemesis Jean-Nöel Jeanneney) about eight new local incarnations of Google Print. (more)

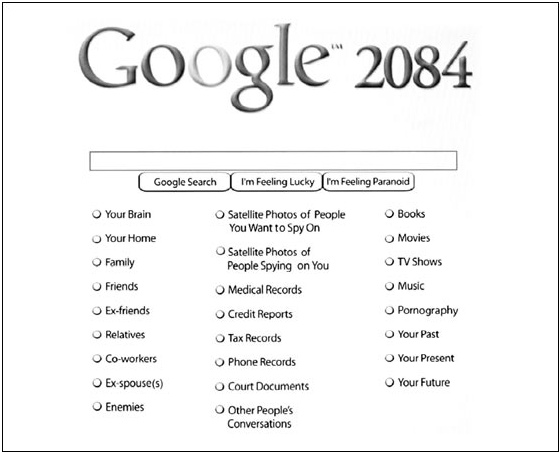

google dystopia

Google as big brother: “Op-Art” by Randy Siegel from today’s NY Times.

yahoo! announces book-scanning project to rival google’s

Yahoo, in collaboration with The Internet Archive, Adobe, O’Reilly Media, Hewlett Packard Labs, the University of California, the University of Toronto, The National Archives of England, and others, will be participating in The Open Content Alliance, a book and media archiving project that will greatly enlarge the body of knowledge available online. At first glance, it appears the program will focus primarily on public domain works, and in the case of copyrighted books, will seek to leverage the Creative Commons.

Google Print, on the other hand, is more self-consciously a marketing program for publishers and authors (although large portions of the public domain will be represented as well). Google aims to make money off its indexing of books through keyword advertising and click-throughs to book vendors. Yahoo throwing its weight behind the “open content” movement seems on the surface to be more of a philanthropic move, but clearly expresses a concern over being outmaneuvered in the search wars. But having this stuff available online is clearly a win for the world at large.

The Alliance was conceived in large part by Brewster Kahle of the Internet Archive. He announced the project on Yahoo’s blog:

To kick this off, Internet Archive will host the material and sometimes helps with digitization, Yahoo will index the content and is also funding the digitization of an initial corpus of American literature collection that the University of California system is selecting, Adobe and HP are helping with the processing software, University of Toronto and O’Reilly are adding books, Prelinger Archives and the National Archives of the UK are adding movies, etc. We hope to add more institutions and fine tune the principles of working together.

Initial digitized material will be available by the end of the year.

More in:

NY Times

Chronicle of Higher Ed.

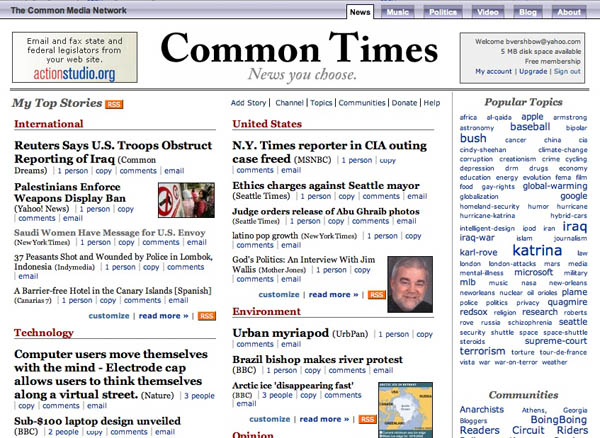

human versus algorithm

I just came across Common Times, a new community-generated news aggregation page, part of something called the Common Media Network, that takes the social bookmarking concept of del.icio.us and applies it specifically to news gathering. Anyone can add a story from any source to a series of sections (which seem pre-set and non-editable) arranged on a newspaper-style “front page.” You add links through a bookmarklet on the links bar on your browser. Whenever you come across an article you’d like to submit, you just click the button and a page comes up where you can enter the metadata like tags and comments. Each user has a “channel” – basically a stripped-down blog – where all their links are displayed chronologically with an RSS feed, giving individuals a venue to show their chops as news curators and annotators. You can set it up so links are posted simultaneously to a del.icio.us account (there’s also a Firefox extension that allows you to post stories directly from Bloglines).

Human aggregation is often more interesting than what the Google News algorithm can turn up, but it can easily mould to the biases of the community. Of course, search algorithms are developed by people, and source lists don’t just manufacture themselves (Google is notoriously tight-lipped about its list of news sources). In the case of something like Common Times, a slick new web application hyped on Boing Boing and other digital culture sites, the communities can be rather self-selecting. Still, this is a very interesting experiment in multi-player annotation. When I first arrived at the front page, not yet knowing how it all worked, I was impressed by the fairly broad spread of stories. And the tag cloud to the right is an interesting little snapshot of the zeitgeist.

(via Infocult)

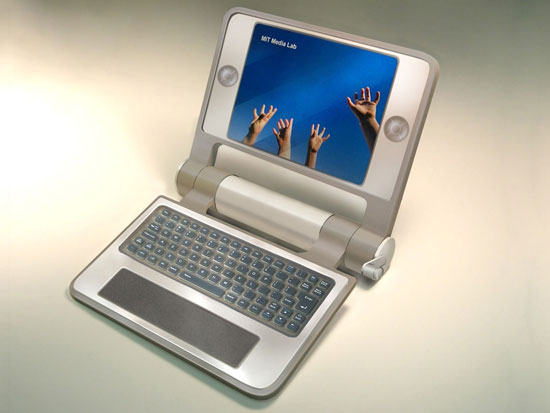

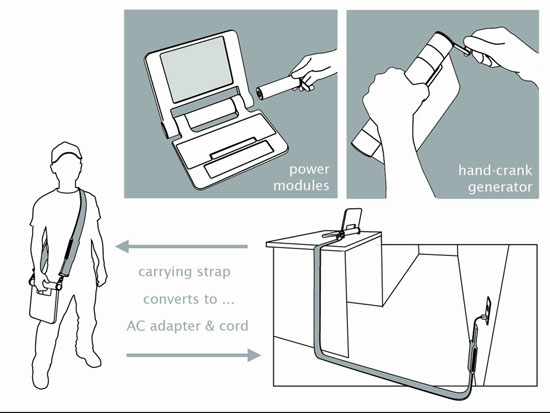

this laptop costs $100

MIT has released some new images of its $100 laptop prototype, of which it hopes to have 5 to 15 million test units within the year. The laptops are much more durable than your average commercial machine, can be used as writing tablets or rotated 90 degrees as ebooks, and run on Linux – 100% free software. The idea is for the machines to provide a platform for an open source education movement throughout the South – a major hack of the current global order.

I love the hand cranks on the side, a backup charging option for remote or poorly provided areas where there is little or no electricity.

(“The $100 laptop moves closer to reality” in CNET)

the database of intentions

Interesting edition of Open Source last week on “Google Sociology” with David Weinberger and John Battelle, author of the just-published “The Search: How Google and Its Rivals Rewrote the Rules of Business and Transformed Our Culture”. Listen here.

Weinberger has some interesting things to say about Google (and the other search engines) as “publishers.” I have some thoughts on that too. More to come later.

Battelle has done a great deal of thinking on search from a variety of angles: the technology of search, the economics of search, and the more esoteric dimensions of a “search” culture. He touches briefly on this last point, laying out a construct that is probably treated more extensively in his book: the “database of intentions.” By this he means the archive, or “artifact,” of the world’s search queries. A picture of the collective consciousness formed by the questions everyone is asking. Even now, when logged in to Google, a history of all your search query strings is kept – your own database of intentions. The potential value of this database is still being determined, but obvious uses are targeted advertising, and more relevant search results based on analysis of search histories.

As regards the collective database of intentions, Battelle speculates that future advances in artificial intelligence will likely draw on this enormous crop of information about how humans think and seek.

google blog search – still a long way to go

Google’s new blog search engine reminds me of how far we still have to go with blog search. The engine works much the same way as Google’s general web search – with keywords and page ranking – only here it’s searching RSS feeds. Recent posts with keyword matches fill the column, and a few links to related blogs come up at the top. But there’s the rub. These so-called “related” blogs are only related by direct keyword matches in their title tagline. I just searched “poetry” and came up with only three related blogs. C’mon. A search for “gossip” turns up only one related blog – “Starbucks Gossip”. There has to be some kind of promotion going on here, though their “about” page mentions nothing of the kind.

A good engine would be capable of searching blogs by their subject, their preoccupation, their obsession. Many blogs could be considered “general,” but just as many have a special focus, and readers are often searching with a particular theme in mind. They don’t just want a list of transient posts, but whole sites that might potentially become regular destinations. Many blogs are valuable publications that prove themselves day after day. But blog search hasn’t yet grown beyond the trendy “what’s the latest chatter on the blogosphere” mode.

I do have to give credit to Technorati. Glitchy as it is, they’re trying to think of creative ways – tagging, author-determined keywords – to help readers find interesting blogs and authors their audience. Then again, my greatest finds have usually been from other blogs. Humans will always be the smartest aggregators.

People out there, what do you use?