Check out this article in today’s Wired News discussing what Amazon might be up to with features like Search Inside the Book, automated recommendations, and user-augmented content such as reader reviews, customer images, Listmania etc. Are these just a bunch of fun toys, or is it all beginning to add up into something big? The article focuses primarily on fancy new search functions – Statistically Improbable Phrases (SIPs), text stats, and concordance (see “amazon: inching toward semantic“) – and includes a few remarks on the subject from if:book..

Category Archives: General

visual politics

Do your political affiliations affect that way you “read” images? A group of graphic designers created Visual Ideology; representing political ideas with images to explore this notion. They pose the question this way: “Given the choice, what images would the general public associate with specific ideas or words? How can one image be more meaningful than another similar image? This project asks viewers to make decisions as to images that best represent their visual definition of political terms or ideas.” I encourage you to try this yourself. After you complete the (often hilarious) visual survey, an interface will tell you exactly who shares your visual politics.

five million words of public domain restored!

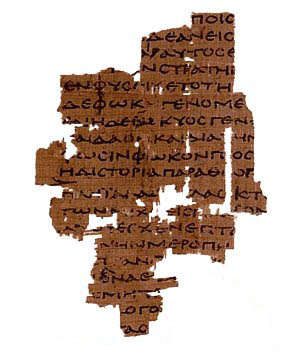

“Once it had walls three miles round, with five or more gates; colonnaded streets, each a mile long, crossing in a central square; a theatre with seating for eleven thousand people; a grand temple of Serapis. On the east were quays; on the west, the road led up to the desert and the camel-routes to the Oases and to Libya. All around lay small farms and orchards, irrigated by the annual flood — and between country and town, a circle of dumps where the rubbish piled up.” (from Waste Paper City by P.J. Parsons)

“Once it had walls three miles round, with five or more gates; colonnaded streets, each a mile long, crossing in a central square; a theatre with seating for eleven thousand people; a grand temple of Serapis. On the east were quays; on the west, the road led up to the desert and the camel-routes to the Oases and to Libya. All around lay small farms and orchards, irrigated by the annual flood — and between country and town, a circle of dumps where the rubbish piled up.” (from Waste Paper City by P.J. Parsons)

It was in this garbage dump, outside the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus in modern-day Egypt, vanished except for a single column, that 400,000 classical manuscript fragments were unearthed by British archaeologists in the late 19th century. It has long been thought that the texts, which reside at Oxford’s Sackler Library, represent a vast number of missing pieces from the known classical canon, in addition to thousands of humdrum documents – petitions, land deeds, wage receipts, orders for arrest, registration of slaves and goats etc. – shedding light on daily life in the Greco-Roman world. The problem is that they are largely unreadable, crushed and mashed together, blackened by years of decay, nibbled by worms. Here and there over the years, individual texts have been deciphered, making waves through the academic world. But now, the Oxyrhynchus Papyri can at last be decoded en masse through the use of multi-spectral imaging, a technique developed in satellite photography, which teases texts to the surface with infra-red light. Hailing it as the “holy grail” of antiquarian discoveries, classicists are predicting a major wave of restoration to the received literary canon, including lost plays of Sophocles and Euripides, a post-Homeric epic by Archilochos, and even missing gospels of the New Testament.

Read article in the Independent, via Grand Text Auto.

boekplaats

out of print is out of date

Amazon.com has recently acquired BookSurge, the self-described “global leader in inventory-free book publishing, printing, fulfillment and distribution.” This adds cutting edge print-on-demand technology to Amazon’s online retailing recipe – big news for self-published authors, but even bigger news for readers. Amazon’s move suggests that print-on-demand might finally be maturing out of the terrible twos of the vanity press into a technology that redefines publishing in space and time. Imagine rare books suddenly coming back into print, and newer books staying in print longer, or indefinitely. Every book, no matter how old or obscure, could theoretically be in print, in perpetuity. Amazon already sells out-of-print or hard-to-obtain titles produced on demand by BookSurge, but their absorbing the company signals a definitive step futher into long tail bookselling. (article)

The backbone of any serious publishing house used to be its backlist – the large catalogue of older titles that sell reliably over time and are therefore kept in print. A backlist might include classics by the country’s most important authors, or books with more modest readership that still sell consistently over the years. It’s like the publisher’s DNA – a map of who they really are. On occasion, you have a runaway bestseller, and you rejoice, but it’s not something you count on. It’s the sturdy, distinguished backlist that keeps a publisher grounded. Today we have the opposite. Most publishing houses have merged under large media conglomerates, backlists have dwindled, and publishers are ever more obsessed with finding their next blockbuster hit – a Dan Brown or Sue Grafton. Books quickly go out of print, and many more – books that might have found a smaller, more select readership – probably never see the light of day since publishers aren’t willing to take on the cost and risk of a smaller print run.

But as Greg Geeley, Amazon.com media products vice president, puts it:

“Print-on-demand has changed the economics of small-quantity printing, making it possible for books with low and uncertain demand to be profitably produced… Thanks to print-on-demand, ‘out of print’ is out of date.”

People have been talking for some time about the internet’s potential to sweep away the stagnation of mainstream publishing. Amazon has already changed the way we browse, buy and discuss books. Now, with machines that can turn out a single book at a time, indistinguishable in appearance and quality from a regular trade paperback or even hardcover, no title need ever go out of print, and publishers might finally be able to direct their attention away from quantity and back to quality.

For further reading…

food for thought

(photograph by Gregory Vershbow)

generation M and the mediated mind

A major study of media consumption habits among American youth (ages 8-18) was released yesterday by the Kaiser Family Foundation. A “representative sample” of over 2,000 3rd through 12th graders were surveyed, including 700 who volunteered to maintain seven-day “media diaries,” charting media consumption in half hour chunks, noting location, company they had, and any simultaneous activities. Findings were announced at a high-profile release in Washington attended by Hillary Clinton and other luminaries.

A major study of media consumption habits among American youth (ages 8-18) was released yesterday by the Kaiser Family Foundation. A “representative sample” of over 2,000 3rd through 12th graders were surveyed, including 700 who volunteered to maintain seven-day “media diaries,” charting media consumption in half hour chunks, noting location, company they had, and any simultaneous activities. Findings were announced at a high-profile release in Washington attended by Hillary Clinton and other luminaries.

The study finds that kids are often multitasking – absorbing several media simultaneously, often at consoles set up in their bedrooms. Average daily exposure is a full third of the day (8.33 hours), which, when combined with approximately a third of the day at school and a third of the day asleep (although most kids are probably not sleeping that much), amounts to nearly every waking, extra-curricular hour spent tuned in, logged on, glued to, etc…

The evidence of multitasking paints a picture of a generation skilled at combining passive and interactive media – the TV is on, but you’re also instant messaging with friends, and doing a bit of quick research on Google for that homework assignment. Constant skimming and constant scattering. Are these fractured minds in the making?

How Do Books Work? A Conversation with Mom

My mother, a veteran kindergarten teacher, who, over the last 30 years, has taught scores of children to read, recently engaged me in an interesting conversation regarding the ebook vs. the paper book. She was responding to something I posted a few months ago called: Children and Books: Forming a World-view. She was particularly interested in this passage:

My son is 14 months old and he loves books. That is because his grandmother sat down with him when he was six months old and patiently read to him. She is a kindergarten teacher, so she is skilled at reading to children. She can do funny voices and such. My son doesn’t know how to read, he barely has a notion of what story is, but his grandmother taught him that when you open a book and turn its pages, something magical happens–characters, voices, colors–I think this has given him a vague sense of how meaning is constructed. My son understands books as objects printed with symbols that can be translated and brought to life by a skilled reader. He likes to sit and turn the pages of his books and study the images. He has a relationship with books, but he wouldn’t have that if someone hadn’t taught him. My point is, even after you learn to read, the book is still part of a complex system of relationships. It is almost a matter of chance, in some ways, which books are introduced to you and opened to you by someone.

My son is 14 months old and he loves books. That is because his grandmother sat down with him when he was six months old and patiently read to him. She is a kindergarten teacher, so she is skilled at reading to children. She can do funny voices and such. My son doesn’t know how to read, he barely has a notion of what story is, but his grandmother taught him that when you open a book and turn its pages, something magical happens–characters, voices, colors–I think this has given him a vague sense of how meaning is constructed. My son understands books as objects printed with symbols that can be translated and brought to life by a skilled reader. He likes to sit and turn the pages of his books and study the images. He has a relationship with books, but he wouldn’t have that if someone hadn’t taught him. My point is, even after you learn to read, the book is still part of a complex system of relationships. It is almost a matter of chance, in some ways, which books are introduced to you and opened to you by someone.

Hi Kim,

I was really touched by the comments about Aidan and me. I truly believe that a child’s first experiences with books (even before he/she can read) are vital to his/her enjoyment of them in later life. I would like to add to your observations about books being intertwined with experiences and how I see very young children learning to love literature.

Much research has been done on how and why children want to learn to read. We know that the single most important thing that parents can do to make an avid reader of their child, is to read to them. We also know that, for most children, it takes approximately 700 to 1000 hours of lap/read time to have them ready to read. That sounds like a great deal of time, but if you put your child in your lap from the time they are 6 months old until they are 5, that is about 3 minutes a day. If you are holding your child close to you and together you read a colorful, well-written and illustrated children’s book, 3 minutes will disappear very quickly. I cannot imagine any 6 month old interested in a book written in a machine. YES, they would be interested in the machine, but the book (the story and the beautiful illustrations) would be lost to the small child. Because–the biggest part of the reading experience for a small child is being able to participate by holding the book themselves, turning the pages, pointing at the pictures, going back to the pages that they most enjoyed, in other words interacting with a handheld book. A machine will not offer this opportunity.

When children come to my preschool/kindergarten classroom the ones who have had many experiences with books have a wealth of background and knowledge that others do not have. Even if they do not read, when they are given the initial literacy exam they have learned by experience how to hold a book, which is the front versus the back, where do you start reading, what’s wrong with this picture? Etc., etc., etc.

Perhaps, I am jumping too far ahead in assuming that all, even children’s books will ultimately be on machines. If this is to be the case, it will DRASTICALLY change the way children are taught to read and how early experiences prepare them for this task.

Thanks mom, this is great. It brought up a few questions, I wonder if you can address them. I agree that the nurturing aspect of reading to a child is most important, but if the child is sitting in my lap while we look at a book on the computer screen, how will the experience be different? Also, I’m trying to understand why paper books are better than screen-based books, if the book progresses by clicking a mouse or touching the screen, why would those actions be less developmentally useful than page turning? Also, why wouldn’t a 6 month old be interested in a screen-based book? Aidan was mesmerized by the baby einstein videos, those are screen-based. When I play dvds on my laptop machine he screams because he wants to touch the keys and I have to restrain him. He loves pushing buttons, clicking my mouse and touching the screen. It seems like these are skills that he will have to learn in this computer-driven world, why not link computers with reading/nurturing/sitting in mom’s lap, etc., from an early age?

Hi Kim,

These are excellent questions and I do not know how to answer them, as no research has been done in that area. (Great place for Ph.D. research, or for another year of grant money.) You are right, a small child is mesmerized by things they see on the TV and on the computer screen. If you, the parent, is holding the child, perhaps the child would get the same nurturing experiences with the book machine as with a hand held book. I have only had experiences and read research about the hand held book, this is a whole new arena. I do agree that young children of this generation will have to have extensive technological knowledge and why not start it early. My kindergartners went to the computer lab once a week for 45 minutes and most of them were totally computer savvy and those that were not caught on quickly, as they are not afraid to experiment. As to the point that pushing a button is as developmentally appropriate as the skill of turning a page, they are very different skills, but if books are to be in ibooks, turning a page will not be a skill that young children need. Basically this is all uncharted territory and these questions are exactly what “the future of the book” should be asking. Bravo!

Parsing the Behemoth: Thought Experiments

Bob talks about the book as metaphor. It is the thing that does the heavy lifting, a technology that allows us to convey our thoughts through a concrete vehicle. This site looks at how that vehicle is changing as a new electronic means of conveying written information begins to come of age.

When asked to imagine a metaphor for “the book,” we come up with something more organic, a lumbering behemoth with a hundred arms, waving anemone-like through the air to catch out particles of human discourse. The creature has some kind of hair or fur entangled with innumerable flotsam and jetsam. It is buzzing with attendant parasitical organisms, and encrusted with barnacles. To ask if the behemoth has a future is not the right question because the book, as we are picturing it in this analogy, is an immortal. The electronic incarnation of the book does not kill the old behemoth, but rather becomes part of it.

In his afterword to “the Future of the Book,” Umberto Eco noted that:

“In the history of culture it has never happened that something has killed something else, something has profoundly changed something else.” We are interested in the nature of this change as it relates to the book and its evolution.

To examine this heavy lifting device, to define and to understand this aggregate behemoth is the project of our “future of the book” blog. To begin, we have initiated a few thought experiments and put forth several questions that we hope will engender productive discourse. We welcome ideas and suggestions for future experiments.

Go to Thought Experiment #1: Three Books That Influenced Your Worldview