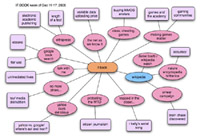

Here’s an overview of what we’ve been posting over the last week. As well, a few of us having been talking about ways to graphically represent text, so I thought I would include a mind map of this overview.

As a follow up to the increasingly controversial wikipedia front, Daniel Brandt uncovered that Brian Chase posted false information about John Seignthaler that was reported here last week. To add fuel to the fire, Nature weighed in that Encyclopedia Britannica may not be as reliable as Wikipedia.

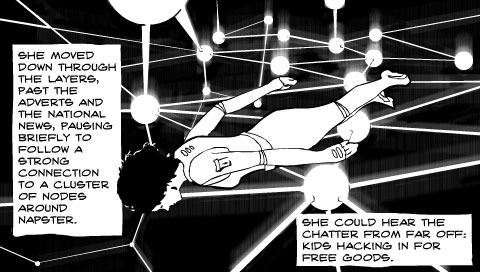

Business Week noted a possible future of pricing for data transfer. Currently, carries such as phone and cable companies are developing technology to identify and control what types of media (voice, images, text or video) are being uploaded. This ability opens the door to being able to charge for different uses of data transfer, which would have a huge impact on uploading content for personal creative use of the internet.

Liz Barry and Bill Wetzel shared some of their experiences from their “Talk to Me” Project. With their “talk to me” sign in tow, they travel around New York and the rest of the US looking for conversation. We were impressed at how they do not have a specific agenda besides talking to people. In the mediated age, they are not motivated by external political/ religious/ documentary intentions. What they do document is available on their website, and we look forward to see what they come up with next.

The Google Book Search debate continues as well, via a panel discussion hosted by the American Bar Association. Interestingly, publishers spoke as if the wide scale use of ebooks is imminent. More importantly and even if this particular case settles out of court, the courts have a pressing need to define copyright and fair use guidelines for these emerging uses.

With the protest of the WTO meetings in Hong Kong this past week, new journalism forms took one step forward. The website Curbside @ WTO covered the meetings with submissions from journalism students, bloggers and professional journalists.

McDonalds filed a patent which suggests that it intends to offer clips of movies instead of the traditional toys in their kids oriented Happy Meals. Lisa pondered if a video clip can successfully replace a toy, and if it does, what the effects on children’s imaginations might be.

R. Kelly’s experiments in form and the “serial song” through his Trapped in the Closet recordings. While R Kelly has varying success in this endeavor, Dan compared the experience of not only the serial novel, but also Julie Powell’s foray into transferring her blog into book form and what she might have learned from R. Kelly (its hard to make unified pieces maintain an overall coherency.)

The world of academic publishing was challenged with a proposal calling to create an electronic academic press. This segment seems especially ripe for the shift to digital publishing as many journals with small circulations face raising printing and production costs.

Sol and others from the institute attended “Making Games Matter,” a panel with contributors from The Game Design Reader: A Rules of Play Anthology, edited by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. The discussion covered among other things: involving the academy in creating a discourse for gaming and game design, obstacles in studying and creating games, and the game “industry” itself. The book and panel called out for games and gaming to undergo a formal study akin to the novel and the experience of reading. Also, in the gaming world, the class economics of the real and virtual began to emerge as a Chinese firm pays employees to build up characters in MMOGs to sell to affluent gamers.

the following is slightly edited analysis of the game by rylish moeller, an english prof who is very active on the

the following is slightly edited analysis of the game by rylish moeller, an english prof who is very active on the