I’ve chosen ‘game culture’ as the theme for this first review post, for all that many of these posts could just as easily be tagged another handful of ways. But games have always hovered at the fringes of debates about the future of the book.

Consideration of serious video games; repurposing of existing games to create machinima, and cultural activities arising out of machinima. Dscussion of more overtly cross-platform activities: pervasive gaming, ARGs and their multiple spawn in terms of commercialization, interactivity, resistance to ‘didactic’ co-optation and more. There’s a lot here; as per my first post on this subject, I’d welcome comments and thoughts.

In February 2005, Sol Gaitan wrote a thoughtful piece about the prevalence of video games in children’s lives, and questioned whether such games might be used more for didactic purposes. In April 2005 Ben picked up an excerpt from Stephen Johnson’s Everything Bad Is Good For You, which pointed to further reading on video games in education. In August 2005, four British secondary schools experimented with educational games; someone died after playing video games for 50 hours straight without stopping to eat; and Sol pondered whether the future of the book was in fact a video game.

Between February and May 2006 the Institute worked on providing a public space for McKenzie Wark’s Gamer Theory – not strictly a game, but a networked meta-discussion of game culture. Discussion of ‘serious’ games continued in an April analysis of why some games should be publicly funded. In August 2006, Sino-Japanese relations became tense in the MMORPG Fantasy Westward Journey; later the same month, Gamersutra wondered why there weren’t any highbrow video games, prompting a thoughtful piece from Ray Cha on whether ‘high’ and ‘low’ art definitions have any meaning in that context.

Machinima and its relations have appeared at intervals. In July 2005 Bob Stein was interviewed in Halo, followed later the same month by Peggy Ahwesh in Halo-based talk show This Spartan Life. Ben wrote about the new wave of machinima and its relatives in December 2005, following this up with a Grand Text Auto call for scholarly papers in January 2006, and a vitriolic denunciation of the intersection between machinima, video gaming, and the virtualization of war (May 2006). In September 2006 McKenzie Wark was interviewed about Gamer Theory in Halo. Then, in October 2007, Chris mentioned the first machinima conference to be held in Europe.

Pervasive gaming makes its first appearance in a September 2006 mention of the first Come Out And Play festival (the 2008 one just wrapped up in NY last weekend). It’s interesting to note how the field has evolved since 2006: where pervasive gaming felt relatively indie in 2006, this year ARG superstar Jane McGonigal brought The Lost Game, part of The Lost Ring, her McDonalds-sponsored Olympic Games ARG

Earlier, overlap between pervasive gaming, ARGs and hoaxes was foreshadowed by an August 2005 story about a BBC employee writing a Wikipedia obituary for a fictional pop star – and then denying that they were gaming the encyclopedia. I wrote my first post about ARGs and commercialization in January 2007, following this with another about ARGs and player interaction in March. The same month, Ben and I got excited about the launch of McGonigal’s World Without Oil, which looked to bring together themes of ‘serious’ and pervasive gaming – but turned out, as Ben and my conversation (posted May 2006) to be rather pious and lacking in narrative.

Since then, both marketing and educational breeds of ARG have spread, as attested by Penguin’s WeTellStories (trailed February, launched March 2008), and the announcement of UK public service broadcaster Channel 4 Education’s move of its £6m commissioning budget into cross-platform projects.

I’m not going to attempt a summary of the above, except to say that everything and nothing has changed: cross-platform entertainment has edged towards the mainstream, didactic games continue to plow their furrow at the margins of the vast gaming industry, and commercialization is still a contentious topic. It’s not clear whether gaming has come closer to being accepted alongside cinema as a significant art form, but its vocabularies have – as McKenzie Wark’s book suggested – increasingly bled into many aspects of contemporary culture, and will no doubt continue to do so.

Category Archives: gaming

more compelling than choice

The first two major ARGs to play out, The Beast and ilovebees, surprised their creators: the collective intelligence of thousands of players was taking down in hours puzzles that the puppetmasters had expected the community to wrestle with for days. And in order for the game not to go stale, new challenges – sometimes created on the fly – had to keep coming. If the content fizzled out, or the puzzles were too easy, the players would become restless and lose interest.

I was reminded of this by the recent discussion on this blog about hypertext. ‘Boring’ is such a loaded word; and yet so much of the Web feels, to me, deeply boring. Even the interesting stuff. Internet addiction is all about clicking across link after link, page after page of content, unable to tear oneself away but still strangely bored. Faced with infinite places to go, all content becomes undifferentiated; lacking in narrative; boring. Much like the paralysis consumers face when confronted with 15 near-identical types of pesto, choice of content made as easy as a click here or there reduces it all to a blur.

I found myself pondering easy choice, supermarket paralysis and internet addiction in the context of the exciting promise and strange underwhelmingness of much hyperfiction. Then, yesterday, interactive game creator and SixToStart ARG writer James Wallis said something that flipped the light on. “Writing for interactive is different to print writing,” he said. But this isn’t in the way someone habituated to storytelling on paper might expect. For such, ‘interactive’ might suggest an exciting opportunity to cast off the formal shackles of one-page-after-the-next. (Certainly, when I first came across HTTP, that’s what it seemed to promise me). “When you think of interactive, you think of the Garden of Forking Paths, non-linear narrative and so on. But if you want people to stay interested, that doesn’t work at all.”

Instead, he says, writing for interactive takes a more or less linear narrative, and makes the reader/user/player work it. In an ARG, a crucial piece of information might be hidden behind a login that needs to be hacked; the story’s progression might depend on a puzzle being solved to reveal a code. The payoff of interactivity, the thing that gives the story a hook that it couldn’t get otherwise, is less about ‘choice’ or a pleasure of diverging from linear narrative, than a sense of active contribution to the progression of that narrative. Of course, because an ARG plays out in real time, players may solve things ‘too’ quickly or take the story in a new direction – then, to avoid shattering the ‘This Is Not A Game’ illusion the puppetmasters must create new content to reflect that divergence.

Earlier, in a comment on the hypertext discussion, I found myself pondering emotional involvement – as measured by whether a story can move you to tears – in the context of interactive narrative. Games that eschew development of ‘characters’ in favor of making you, the central protagonist, the ‘character’ that develops. Tearjerking moments in 1983 text-based adventure games. How does a character or situation creep up on us so that we care enough to be sad when they’re gone?

Perhaps it’s easier to let this happen when you’re being swept along by a movie, or barely noticing as you turn page after page. I can’t prove this, but it feels as though having to make empty, consequence-free choices about where a narrative goes next pulls me back from imaginative involvement to a more meta-level, strategic, structural kind of thinking, that’s inimical to emotional absorption. It’s a bit like something pulling me back from an exciting moment in my book and inviting me to contemplate the paper. Forcing me to choose between narrative possibilities, when that choice has (as in the supermarket, faced with the rows of pesto choices) no consequences, and implying too – as the supermarket does – that choice were in itself a positive addition to my experience, in fact undermines my ability to relax into that experience. Compare that to a hidden group of puppetmasters evolving a narrative on the fly to fit around an amorphous, self-organizing group of players, going to extraordinary lengths to avoid rupturing the story’s consistency, and you can see that here are radically different kinds of ‘interactive’.

Making you work for the next chunk of story, or making you the central protagonist. If these are two narrative tools that demonstrably help make stories work in a digital space, are there more? And are they perceived as markers for quality interactive fiction? Or are game-like narratives still considered somehow a ‘lower’ art form, nerdy and plebeian, unsuitable for ‘serious’ writing or consideration as powerful narrative? I would welcome any evidence to the contrary.

stencil hypertext

Not sure if it’s been washed away yet, but folks in the Bay Area should keep an eye out for this charming urban hypertext:

The mission stencil story is an interactive, choose-your-own-adventure story that takes place on the sidewalks of the Mission district in San Francisco. It is told in a new medium of storytelling that uses spraypainted stencils connected to each other by arrows. The streetscape is used as sort of an illustration to accompany each piece of text.

More images and some press links on this Flickr photoset.

(Thanks sMary!)

“highbrow” video games?

Recently in the gaming blog Gamersutra, Ernest Adams questions why aren’t there highbrow video games.” His article comes one month after an Esquire article, where Chuck Klosterman wondered why isn’t there good video game criticism and makes the claim that video games needs its own Lester Bangs. As the video game market grows, it is not surprising that fans and advocates of gaming will want to form to grow and mature as well.

Recently in the gaming blog Gamersutra, Ernest Adams questions why aren’t there highbrow video games.” His article comes one month after an Esquire article, where Chuck Klosterman wondered why isn’t there good video game criticism and makes the claim that video games needs its own Lester Bangs. As the video game market grows, it is not surprising that fans and advocates of gaming will want to form to grow and mature as well.

Adams’ call for “highbrow” games is rooted in a desire to add creditability and legitimacy to video games. As someone who has dedicated his career to making and writing about video games, the never-ending criticism about the violence in games by various groups looking for easy political targets must be frustrating to endure. I can appreciate the motivations behind Adam’s conclusion, however, his description of highbrow video games is ultimately too narrowly defined and overlooks impressive experiments of video games.

I hesitate to even try to deem games “high” or “low” because the terms are not that useful. Adams specifically points out that the films he aspires video games to emulate are not “art films,” which he describes as a “short low-budget titles filled with impenetrable weirdness.” Therefore, his definition of highbrow edge towards the problematic “I know it when I see it” definitions of art. Further, we can gather insight on culture and ourselves by interacting will both high and low culture and valuing one form over another is problematic.

From his description of a highbrow video game, I think what Adams is really asking for is better interactive narratives in gaming. He alludes to the films of Ishmail Merchant and James Ivory, who are best known for adopting the novels of E.M. Forester, often with screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Their films tend to be beautiful, well crafted analyses of class. Although, they are not generally know for pushing the boundaries of film.

Last year, Adams gave a talk which he published on his website, in which he assesses the state of interactive narrative. It provides more insight on his train of thought. In it, one of his references in video game scholarship is Janet Murray’s Hamlet on the Holodeck which uses a theatrical frame of reference in postulating the future of interactive narrative. Also, Adams offers a model of a “structured” approach to the narrative of video games and reveals that he is particularly wedded to the idea of single player games over the shared gaming experience of MMORPGs which are increasingly popular. In his current essay, his description of states that the highbrow video game “would reward close attention and playing more than once.” This implies that he still leans towards single player role playing games in his conceptualization of highbrow games.

However, video games that are pushing the form in more “artistic” ways are occurring outside the bounds of single player game. For example, we-make-money-not-art reported on The Endless Forest, which is a gorgeous MMORPG in which players assume the identity of a deer. Developed by the Belgian studio Tale of Tales, The Endless Forest has an elegant interface and darkly rich art direction. Although it lacks an explicit narrative, the gameplay engages users without the typical violence and sexually charged themes of many games. The Endless Forest limits the use of language. Therefore, it does not include a chat function and players are “named” with pictograms rather than words. However, as more of these kinds of games are created, they are unlikely to lessen the criticism of the negative social effects of video games.

As for criticism, the notion of elevating video game criticism to a higher form is rather ironic, as it comes at the same time when the New York Times critic A.O. Scott finds himself defending film criticism. While not a music critic, Scott describes the critics’ predicament that often panned movies are still hugh box offices successes. Media critics want the new and interesting, which is somewhat expected if it is your job to watch and write about movies, music, or video games everyday. Their standards are quite different from the typical audience member. Lester Bangs was a polarizing figure, who wanted to raise the standards of writing on music. He appeared at a time when people were ready for similar standards. It may be that a critical mass of audience for a similar kind of criticism for gaming is beginning to emerge.

As previously stated, most gamers will still want “mainstream” titles. Because games are expensive, they will still rely on criticism which Klosterman dismissives as “customer advice.” That is, many gamers, if not most, will still mostly be interested in reading reviews which describe gameplay, graphics and sound design, rather than thematic and issues of meaning. Many gamers don’t like the academic scholarly writing on video games, which is in adbundance, but is not what Klosterman wants to read. We learned about their attitutdes in initial reactions and comments posted across the gaming blogosphere about our project “GAM3R 7H30RY.” It’s not clear to me what is bad about gaming publications serving the desires of the video game playing community.

My guess is that both boundary pushing video games and criticism will be begin to get more exposure fairly soon. For the actual video games, I would look towards Europe and Asia, where more government funding exists for developing these kinds of endeavors. I don’t expect many of the big gaming companies in the US to create experimental games of this nature. Although, they might in the future, after the proven economic viability of them. In that, major movie studios started funding more smaller films after they saw successful crossover of films of the Merchant Ivory variety. Although, Rockstar (the maker of Grand Theft Auto) have the upcoming and already controversial game Bully, where you must navigate a boarding school as a new student. It was described by the New York TImes as having, “an open world for the players to explore, tightly defined and memorable characters, a strong story line, [and] high-end voice acting,” which is precisely what Adams call for in his article.

My guess is that both boundary pushing video games and criticism will be begin to get more exposure fairly soon. For the actual video games, I would look towards Europe and Asia, where more government funding exists for developing these kinds of endeavors. I don’t expect many of the big gaming companies in the US to create experimental games of this nature. Although, they might in the future, after the proven economic viability of them. In that, major movie studios started funding more smaller films after they saw successful crossover of films of the Merchant Ivory variety. Although, Rockstar (the maker of Grand Theft Auto) have the upcoming and already controversial game Bully, where you must navigate a boarding school as a new student. It was described by the New York TImes as having, “an open world for the players to explore, tightly defined and memorable characters, a strong story line, [and] high-end voice acting,” which is precisely what Adams call for in his article.

Regardless of who moves video games and its coverage further, it’s bound to happen. Although, these new forms may not look exactly has Adams and Klosterman describe or wish. Media takes time to evolve, just compare the “highbrow” television series the HBO produces as compared to rather “lowbrow” television from the 50s. (I will admit that I don’t prefer one over the other.) For a great example of how a medium transforms the perspective of an artist, see Scott McCloud’s description of the movement from comic book fan to student to professional to genre pushing pioneer in Understanding Comics. If someone really wants to write video game criticism in the style of Lester Bangs, then the current low barriers of entry to electronic self-publishing allows her to do so. Creating video games, of course, requires a lot more resources. However, in closing, Adams states, “maybe I’ll design one myself, just for the fun of it.”

controversy in a MMORPG

Henry Jenkins gives a fascinating account of an ongoing controversy occurring in a MMORPG in the People’s Republic of China, the fastest growing market for these online games. Operated by Netease, Fantasy Westward Journey (FWJ) has 22 million users, with an average of over 400,000 concurrent players. Last month, game administrators locked down the account of an extremely high ranking character, for having an anti-Japanese name, as well as leading a 700 member guild with a similarly offensive name. The character would be “jailed” and his guild would be dissolved unless he changed his character and guild’s name. The player didn’t back down and went public with accusations of ulterior motives by Netease. Rumors flew across FWJ about its purchase by a Japanese firm which was dictating policy decisions. A few days late, an alarming protest of nationalism broke out, consisting of 80,000 players on one of the gaming servers, which was 4 times the typical number of players on a server.

The ongoing incidents are important for several reasons. One is that it is another demonstration of how people (from any nation) bring their conceptualization of the real world into the virtual space. Sino-Japanese relations are historically tense. Particularly, memories of war and occupation by the Japan during World War II are still fresh and volatile in the PRC. In a society whose current calender year is 4703, the passage of seventy years accounts for a relatively short amount of time. Here, political and racial sentinment seamlessly interweave between the real and the virtual. However, these spaces and the servers which house them are privately owned.

The second point is that concentrations of economic and cultural production is being redistributed across the globe. The points where the real and the virtual worlds become porous are likewise spreading to places throughout Asia. Therefore, coverage of these events outside of Asia should not be considered fringe, but I see important incentives to track, report and discuss these events as I would local and regional phenomenon.

sonogram of networked book in embryo (GAM3R 7H30RY part 3)

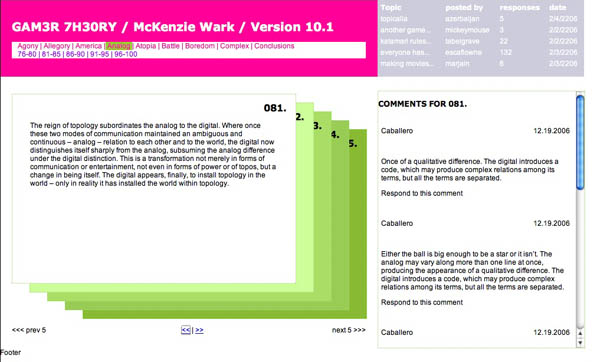

It probably won’t be until mid to late March that we finally roll out McKenzie Wark’s GAM3R 7H30RY Version 10.1, but substantial progress is being made. Here’s a snapshot:

After debating (part 1) our way to a final design concept (part 2), we’re now focused (well, mainly Jesse at this point) on hammering the thing together. We’re using all open source software and placing the book under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 license. Half the site will consist of a digital edition of the book in Word Press with a custom-built card shuffling interface. As mentioned earlier, Ken has given us an incredibly modular structure to work with (a designer’s dream): nine chapters (so far), each consisting of 25 paragraphs. Each chapter will contain five five-paragraph stacks with comments popping up to the side for whichever card is on top. No scrolling is involved except in the comment field, and only then if there is a substantial number of replies.

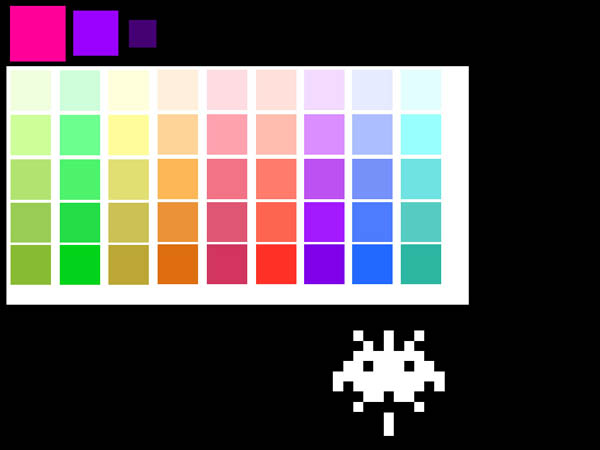

The graphic above shows the color scale we’re thinking of for the different chapters. As they progress, each five-card stack will move from light to dark within the color of its parent chapter. Floating below the color spectrum is the proud parent of the born-digital book: McKenzie Wark, Space Invader (an image that will appear in some fashion throughout the site). Right now he’s a fairly mean-looking space invader — on a bombing run or something. But we’re thinking of shuffling a few pixels to give him a friendlier appearance.

You are also welcome to view an interactive mock-up of the card view (click on the image below):

The other half of the site will be a discussion forum set up in PHP Bulletin Board. Actually, it’ll be a collection of nine discussion forums: one for each chapter of the book, each focusing (except for the first, which is more of an introduction) on a specific video game. Here’s how it breaks down:

* Allegory (on The Sims)

* America (on Civilization III)

* Analog (on Katamari Damarcy)

* Atopia (on Vice City)

* Battle (on Rez)

* Boredom (on State of Emergency)

* Complex (on Deus Ex)

* Conclusions (on SimEarth)

The gateway to each forum will be a two-dimensional topic graph where forum threads float in an x-y matrix. Their position in the graph will be determined by the time they were posted and the number of comments they’ve accumulated so far. Thus, hot topics will rise toward the top while simultaneously being dragged to the left (and eventually off the chart) by the progression of time. Something like this:

At this point there’s no way of knowing for sure which part of the site will be more successful. The book view is designed to gather commentary, and Ken is sincerely interested in reader feedback as he writes and rewrites. There will also be the option of syndicating the book to be digested serially in an RSS reader. We’re very curious to see how readers interact with the text and hope we’ve designed a compelling environment in which to do so.

Excited as we are about the book interface, our hunch is that the discussion forum component has the potential to become the more vital half of the endeavor. The forum will be quite different from the thousands of gaming sites already active on the web in that it will be less utilitarian and more meditative in its focus. This won’t be a place for posting cheats and walk-throughs but rather a reflective space for talking about the experience of gaming and what players take games to mean. Our hope is that people will have quite a bit to say about this — some of which may end up finding its way into the book.

Although there’s still a ways to go, the process of developing this site has been incredibly illuminating in our thinking about the role of the book in the network. We’re coming to understand how the book might be reinvented as social software while still retaining its cohesion and authorial vision. Stay tuned for further developments.

GAM3R 7H30RY: a work in progress… in progress

I’m pleased to report that the institute is gearing up for another book-blog experiment to run alongside Mitchell Stephens’ ongoing endeavor at Without Gods — this one a collaboration with McKenzie Wark, professor of cultural and media studies at the New School and author most recently of A Hacker Manifesto. Ken’s next book, Gamer Theory, is an examination of single-player video games that comes out of the analytic tradition of the Frankfurt School (among other influences). Unlike Mitch’s project (a history of atheism), Ken’s book is already written — or a draft of it anyway — so in putting together a public portal, we are faced with a very different set of challenges.

As with Hacker Manifesto, Ken has written Gamer Theory in numbered paragraphs, a modular structure that makes the text highly adaptable to different formats and distribution schemes — be it RSS syndication, ebook, or print copy. We thought the obvious thing to do, then, would be to release the book serially, chunk by chunk, and to gather commentary and feedback from readers as it progressed. The trouble is that if you do only this — that is, syndicate the book and gather feedback — you forfeit the possibility of a more free-flowing discussion, which could end up being just as valuable (or more) as the direct critique of the book. After all, the point of this experiment is to expose the book to the collective knowledge, experience and multiple viewpoints of the network. If new ideas are to be brought to light, then there ought to be ways for readers to contribute, not just in direct response to material the author has put forth, but in their own terms (this returns us to the tricky proprietary nature of blogs that Dan discussed on Monday).

So for the past couple of weeks, we’ve been hashing out a fairly ambitious design for a web site — a blog, but a little more complicated — that attempts to solve (or at least begin to solve) some of the problems outlined above. Our first aim was to infuse the single-author book/blog with the democratic, free-fire discussion of list servers — a feat, of course, that is far easier said than done. Another concern, simply from an interface standpoint, was to find ways of organizing the real estate of the screen that are more intuitive for reading.

Another thing we’ve lamented about blogs, and web sites in general, is their overwhelming verticality. Vertical scrolling fields — an artifact of supercomputer terminals and the long spools of code they spit out — are taken for granted as the standard way to read online. But nowhere was this ordained as the ideal interface — in fact it is designed more for machines than for humans, yet humans are the users on the front end. Text does admittedly flow down, but we read left to right, and its easier to move your eye across a text that is fixed than one that is constantly moving. A site we’ve often admired is The International Herald Tribune, which arranges its articles in elegant, fixed plates that flip horizontally from one to the next. With these things in mind, we set it as a challenge for ourselves to try for some kind of horizontally oriented design for Ken’s blog.

There’s been a fairly rigorous back and forth on email over the past two weeks in which we’ve wrestled with these questions, and in the interest of working in the open, we’ve posted the exchange below (most of it anyway) with the thought that it might actually shed some light on what happens — from design and conceptual standpoints — when you try to mash up two inherently different forms, the blog and the book. Jesse has been the main creative force behind the design, and he’s put together a lovely annotated page explaining the various mockups we’ve developed over the past week. If you read the emails (which are can be found directly below this paragraph) you will see that we are still very much in the midst of figuring this out. Feedback would be much appreciated. (See also GAM3R 7H30RY: part 2).

letters from second life

Last week, Bob mentioned that Larry Lessig, law profressor and intellectual property scholar, was being interviewed in Second Life, the virtual world created by Linden Lab. Having heard a lot of Second Life before, I was pleased to have a reason and opportunity to create an account and explore it. Basically I quickly learned that it’s Metaverse, as described in Neil Stephenson’s Snowcrash, in operation today, and I’m now a part of it too.

I already covered the actual interview. Here are a few observations from my introduction to SL.

Second Life is a humbling place, especially for beginners. Everything ,even the simplest things, must be relearned. It took me 5 minutes to learn how to sit down, another 5 minutes to read something, and on and on. Traveling to the site of Lessig event was an even more daunting task. I was given the location of this event, a name and coordinates, without any idea of what to do with them. Second Life is a vast space, and it wasn’t clear to me how to get from one point to another. I had no idea how to travel in SL, and had to ask around someone.

I presume it is evident that I’m very new to SL, by my constant trampling over people and inanimate objects. So, I continue walking into trees and rocks until I come across someone whose title contains “Mentor,” and figure that this is a good person to ask for help. Not knowing how to strike up a private conversation, I start talking out loud, not even sure if anyone is even going to pay attention.

(I will come to learn that you travel from place to place via teleportation.)

“Hi.”

“Hi Harold.”

I am relieved to discover that people are basically nice in SL, maybe even nicer than in New York. This fellow avatar is happy to chat and answer questions. Second List has a feature called “Friends” which operates like Buddies in Instant Messaging. However, I’m not sure what the social protocol for making friends is, so I make no assumptions. As I was typing “can we be friends?” I sigh with the realization that I am, in fact, back in fourth grade.

People around me have much more sophisticated outfits than I do. So, I try out the free clothing features. I darken my pants to a deep blue and my shoes black. Then, my default shirt gets turned into a loose white t-shirt. Somehow I end up a bit like a GAP model crossed with Max Headroom. After making my first “friend,” another complete stranger comes up to me and just starts giving me clothes. Apparently, my clothes still need a little work. I try on the cowboy boots and faded jeans. Happy that I’ve moved beyond the standard issue clothes, I thank my benefactor and begin to make my way to the event.

People around me have much more sophisticated outfits than I do. So, I try out the free clothing features. I darken my pants to a deep blue and my shoes black. Then, my default shirt gets turned into a loose white t-shirt. Somehow I end up a bit like a GAP model crossed with Max Headroom. After making my first “friend,” another complete stranger comes up to me and just starts giving me clothes. Apparently, my clothes still need a little work. I try on the cowboy boots and faded jeans. Happy that I’ve moved beyond the standard issue clothes, I thank my benefactor and begin to make my way to the event.

The builders of Second Life force people to rely on other people within the virtual world. However, assistance in the real world certainly helps too. Entering Second Life, the feeling of displacement is quite clear, as if I arrived to a new city in the real world with a single address, where I don’t know anyone or how to navigate the city. The virtual world often mimics the real world, but my surprise each time I learn this fact is still ongoing. It definitely helps to know people, both in where to go that’s interesting and how to do things.

After teleporting to the event, I found myself around people who had common interests, which was great and similar to attending a lecture in the real world. At different times, I struck up a conversation with an avatar who is a publisher on the West Coast and then talked to an academic who runs a media center. In both cases, I was talking to the person literally “next” to me.

When I first heard about the interview, I learned at there was limited spacing. Which seemed strange to me, as it was taking place in a viritual space. When I arrived at the event place, I saw the ampitheater with video screens, that would show a live web stream of Lessig. The limited seating made more sense, seeing the seat of the theater. I also believe that the SL servers also have a finite capacity for the number of people to be located within a small area, because movement was jerky around concentrated groups of people. I guess I’ll have to wait for the Second Life Woodstock.

The space was crowded with people walking around, chatting, and getting up their free digital copy of Lessig’s book, “Free Culture.” (I’ve included a picture of me reading Free Culture in Second Life. You can actually read the text.)  The interview is about to begin, as an avatar with large red wings walks by me. I say out loud, “I know she was going to sit in front of me.” Adding, “Just kidding,” in case I might be offending someone, who knows who this person could be. Fortunately, she found a seat outside my sight line without incident, and the introductory remarks began.

The interview is about to begin, as an avatar with large red wings walks by me. I say out loud, “I know she was going to sit in front of me.” Adding, “Just kidding,” in case I might be offending someone, who knows who this person could be. Fortunately, she found a seat outside my sight line without incident, and the introductory remarks began.

There was a strange duality where I had to both learn what was being said, but also how to navigate the environment of a lecture as well. The interview proceeds within the social norms of a lecture. People are mostly quiet, clap and for the moderator runs the question and answer session. Afterwards, I line up to get Lessig to “sign” my virtual book at the virtual booksigning, as in my virtual public event. I finally stumble my way through the line, all the while asking many question on what I’m supposed to do. With my signed book in hand, I look at the sky, which is quite dark. I log out and return to the real world.

holiday round up

The institute is pleased to announce the release of the blog Without Gods. Mitchell Stephens is using this blog as a public workshop and forum for his work on his latest book which focuses on the history of atheism.

The wikipedia debate continues as Chris Anderson of Wired Magazine weighs in that people are uncomfortable with wikipedia because they cannot comprehend that emergent systems can produce “correct” answers on the marcoscale even if no one is really watching the microscale. Lisa poses that Anderson goes too far in the defense of wikipedia and that blind faith in the system is equally disconcerting, if not more so.

ITP Winter 2005 show had several institute related projects. Among them were explorations in digital graphic reinterpretation of poetry, student social networks, navigating New York through augmented reality, and manipulating video to document the city by freezing time and space.

Lisa discovered an interesting historical parallel in an article from Dial dating back to 1899. The specialized bookseller’s demise is lamented with the introduction of department store selling books as lost leader, not unlike today’s criticisms of Amazon. As libraries are increasing their relationships with the private sector, Lisa notes that some bookstores are playing a role in fostering intellectual and culture communities, a role which libraries traditionally held.

Lisa looked at Reed Johnson assertion in the Los Angeles Times that 2005 was the year that mass media has given way to the consumer-driven techno-cultural revolution.

The discourse on game space continues to evolve with Edward Castronova’s new book Synthetic Worlds. As millions of people spend more time in the immersive environments, Castronova looks at how the real and the virtual are blending through the lens of an economist.

In another advance for content creation volunteerism, LibriVox is creating and distributing audio files of public domain literature. Ranging from the Wizard of Oz to the US Constitution, Lisa was impressed by the quality of the recordings, which are voiced and recorded by volunteers who feel passionate about a particular work.

line between the real and game space… a peek into the future?

As Lisa noted in her comment to an previous post on class and gaming, the Economist reviewed the new book by Edward Castronova entitled, Synthetic Worlds : The Business and Culture of Online Games.

Castronova, also wrote an essay that was included in the Game Design Reader that was behind the “Making Games Matter” panel we attended. This essay marks the first analysis of the economics of people and their interactions in a virtual reality. Interesting to note, it has yet to be formally published in an academic economics journal.

In these studies, Castronova calculates the economics of the virtual by looking at what people are willing to pay in real currency for online gaming characters and their associated costs. As previously posted, people are making their livings in these virtual spaces by creating and selling their avatars. We are entering an era where the boundaries between the real and virtual are blurring.

Although some affluent gamers are buying their way into the higher echelons of game spaces such as EverQuest, there is still the opportunity for anyone with enough time and skill to create advanced characters. Where as in the real world, there are only a limited number of players in the NBA and CEO positions in the Fortune 500 companies. There is enough “room” in the game space to allow for many top tier characters, because the vast majority of the “normal” characters are bots run by the gaming engine.

Is the online game space the utopian society where everyone can be equal and rich and powerful? Is this a peek at the future of the real world when robots take over all the jobs that people don’t want to perform?