just finished the second book discussion at the institute. first was neil postman’s building a bridge to the eighteenth century. second was steve johnson’s everything bad is good for you in which johnson presents a contemporary refutation of postman.

johnson’s basic premise seems harmless enough. games and tv drama are getting more layered, more complex. the mental exercise is likely making our brains more nimble, might even be improving our problem-solving skills. OK…

johnson’s basic premise seems harmless enough. games and tv drama are getting more layered, more complex. the mental exercise is likely making our brains more nimble, might even be improving our problem-solving skills. OK…

but how can you define good and bad simply in terms of whether one’s brain is better at multi-tasking and problem-solving. i’ll grant that this shift in raw brain power might make us more effective worker bees for our techno-capitalist society, but it doesn’t mean that the substance of our lives or the social fabric is improved.

we don’t need cheerleaders telling us everything is fine — especially when in our gut we’re pretty sure it isn’t. we need to look long and hard at the kind of world we are building with all this technology.

johnson’s book has been widely praised, making it all the more important to hold it up to careful scrutiny. over the next several days we’re going to launch a serious critique of “everything bad is good for you.” please feel encouraged to join in.

Category Archives: Games

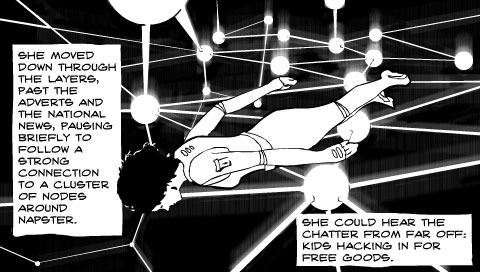

nyc2123: a graphic novel for psp

NYC2123 is a graphic novel conceived for the 480 by 272-pixel screen of the Play Station Portable video game device. It’s a post-apocalyptic tale set in a future, tsunami-ravaged New York in which the city’s wealthy have walled off the island of Manhattan against a violent river society of junkies, thieves and outlaw barges.

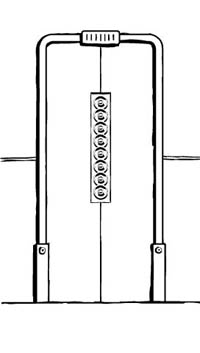

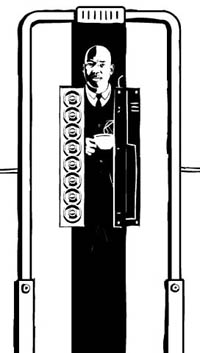

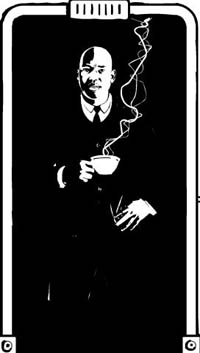

There are several sequences that read like a flip book, taking advantage of the single-frame interface and the fact that the reader has literally got his finger on the button. Quickly flipping through the panels creates a filmic effect, as here:

![]()

![]()

(Once again via Infocult – thanks Bryan)

Update: Someone has just developed a .pdf reader for the PSP.

“imaginative keyword conversations” – playing flickr on public screens

A wonderful hack of public space in Amsterdam. And on the top floor of the PostCS building no less, with breathtaking panoramic views of the city. Kim and I had the pleasure of spending two days there this past January at “A Decade of Web Design.”

The diners in bar/restaurant/club 11 will be subjected to the wrath of fellow visitors SMSing whatever keyword they want to the installation that pulls photos from the online community flickr and projects them onto Restaurant 11’s huge panoramic screens.

(via Smart Mobs)

thoughtful intertextuality

New Orleans DoubleQuotes by Charles Cameron plays with juxtaposition, cleverly pairing bits of text in ways that illuminate Katrina and all that flows from it:

Think of these paired quotes as twin thoughts dropped into the mind-pond — not so much for their own sakes as for the sake of the ripples and resonances between them. I invite you to read these DoubleQuotes one pair at a time, slowly, slowly, so that the multiples ironies and quiet nuances that have come together in the weaving of this tragedy have room to breathe.

(thanks, Bryan Alexander of Infocult)

play station portable as online reading device

The new updated Sony PSP portable gaming device will include a web browser. That gives it games, film, photo and web – the most comprehensive pocket instrument out there. But for the time being, it’s read-only. Without a stylus, or virtual keyboard, many of the web’s more interactive elements will be unavailable.

is the future of the book a video game?

“What ultimately sets gaming apart from prefabricated media like television and books is that the consumer is in control of the action; the consumer is the protagonist of whatever story the game might tell.”

Seth Schiesel affirms this in an article on The Godfather video game coming out early next year (“How to Be Your Own Godfather,” NY Times, July 10, 2005 – also audio slideshow narrated by Schiesel). Schiesel’s article intrigued me from the view point of the movie junkie and the book lover. The Electronic Arts team that created this video game, used scenes and characters from the first Godfather to create a virtual universe where the players can manipulate the plot and create their own narrative. This player becomes the ideal reader that Flaubert and Borges dreamt about, and that the French literary theorists wrote about. Reading/playing becomes writing. The desire to directly involve the reader/audience in the creative act can be traced to the notion of catharsis in Greek tragedy, to Shakespeare’s play inside a play, to the second part of Don Quijote and so on, but it is now, thanks to electronic media, that the concept becomes reality, a virtual reality with all its possibilities yet to be explored.

![]()

![]()

Much has been said about the difficulty to faithfully adapt books to film. García Márquez, whose first love is film, defends his refusal to sell the rights of One Hundred Years of Solitude to Hollywood, saying that the screen robs the viewer the freedom of completing the characters of the novel in his imagination. His readers can, for instance, identify José Arcadio Buendía with an uncle or a grandfather. But, he argues, if that character were to be played by Robert Redford, that freedom of association would be lost. It would also be quite difficult to re-create on film the complex time structure of García Márquez’s novel, or to render credible the many instances of magical realism that, when reading, one doesn’t doubt for a second. Could this be done using electronic media?

![]()

![]()

The executive producer of the Godfather video game, David DeMartini, talks about time linearity in film, usually limited to 80 -120 minutes, in which the director has to provide his narrative version of a book. What is interesting in the use of a movie, based on a novel, as a video game is that the player actually goes through the story living it. Here, he doesn’t only complete the characters in his imagination; he is his own character. Time is not limited or externally imposed upon the player/viewer as in film, he actually has 20, 30, 40 hours to experience and deal with the many choices he has as a character of the narrative. What we have here is not only the ideal reader; it’s the ideal fiction. Brando, who absolutely bought into this project, puts it clearly; “It’s the audience, really, that’s doing the acting.” Incidentally, the BBC reports today that a similar video game franchise is to be made from the Jason Bourne novels of Robert Ludlum – or rather, from the popular films starring Matt Damon adapted from Ludlum’s books.

Francis Ford Coppola, on the other hand, disapproves of the game as a typically violent kill and get killed video game. Seth Schiesel makes an important argument in favor of games bringing the Grand Theft Auto series as a parallel to the Godfather, by saying that there is something more than just violence in these kinds of video games.

![]()

![]()

What is exciting is the game’s form. In G. T. A. the player has an entire city to explore. There are missions and a story available, and plenty of violence, but there is also the freedom one has to experience an open-ended virtual urban environment. I dare to add: what I see here is the book of the future.

computer games in british schools, and, death by gaming

![]() Four secondary schools in Britain (ages 11-16) are to incorporate computer games into daily classroom activities as part of a one-year trial run. Researchers are looking to begin drafting a “road map” for game integration in schools across Europe. See BBC: “Games to be tested in classrooms.”

Four secondary schools in Britain (ages 11-16) are to incorporate computer games into daily classroom activities as part of a one-year trial run. Researchers are looking to begin drafting a “road map” for game integration in schools across Europe. See BBC: “Games to be tested in classrooms.”

Another BBC item: “S Korean dies after games session.” Seems a 28-year-old man became so immersed in Starcraft that he neglected to eat or sleep. After 50 hours, his heart stopped.

(image is a screenshot from Starcraft)

family values and the value of video games

Steven “Everything Bad Is Good For You” Johnson has an amusing open letter to Hillary Clinton in today’s LA Times, urging the senator not to blind herself to the virtues of video games in her quest to earn moral values cred with 2008 swing voters.

Consider this one fascinating trend among teenagers: They’re spending less time watching professional sports and more time simulating those sports on Xbox or PlayStation. Now, which activity challenges the mind more — sitting around rooting for the Packers, or managing an entire football franchise through a season of “Madden 2005”: calling plays, setting lineups, trading players and negotiating contracts? Which challenges the mind more — zoning out to the lives of fictional characters on a televised soap opera, or actively managing the lives of dozens of virtual characters in a game such as “The Sims”?

peggy ahwesh interviewed on “this spartan life”

Following Bob’s foray into game space, experimental filmmaker Peggy Ahwesh takes the plunge in the second interview on “This Spartan Life,” a new talk show filmed in the world of the “Halo” video game series. In 2001, Ahwesh made a Machinima film of her own called “She Puppet” (Machinima is cinema made inside a game engine) using footage culled from months playing the “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider” game. So it doesn’t take long for her to feel right at home. This latest interview takes us through some truly spectacular landscapes and “fantasy architecture,” and, of course, features the customary random bursts of violence (not to mention teleportation and a little skull-dribbling).

I think the Spartan Life folks have a good concept here. The conversations are interesting, but what makes them even more compelling is the fact that an exploration is taking place. It’s like walking around in an abandoned film set. Much of it is tongue-in-cheek. “Sometimes you really feel like you’re running through this insane maze, and somebody’s always scoping in on you,” says host Damian Lacedaemion, his helmeted head framed in someone’s crosshairs. “There’s this constant threat of violence hanging in the air around here.” But there’s an element of genuine wonder as well. Two strangers explore a bizarre new world, a world normally governed by rules and a quest. But they are simply rovers, and there is no quest. There is only curiosity and play. As Damian says: “sometimes I think it feels like being in a movie that’s waiting for you to set it in motion.”

walking around inside a book – bob’s interview in halo space

A couple of months ago, Bob did a rather unusual interview for This Spartan Life, a new online talk show set in the world of Halo video game series. I just received word that the first episode is now up. The show is hosted by Damian Lacedaemion, a hulking, bionic warrior sporting a thousand pounds of body armor, a visored helmet, and what looks like an enormous, ion-charged hair clip. Ordinarily, this character would be blazing his way through an interplanetary battle zone, but here, he’s chatting it up with Bob (also represented by a fearsome armor-plated commando) about the future of books. The effect is truly bizarre.

A couple of months ago, Bob did a rather unusual interview for This Spartan Life, a new online talk show set in the world of Halo video game series. I just received word that the first episode is now up. The show is hosted by Damian Lacedaemion, a hulking, bionic warrior sporting a thousand pounds of body armor, a visored helmet, and what looks like an enormous, ion-charged hair clip. Ordinarily, this character would be blazing his way through an interplanetary battle zone, but here, he’s chatting it up with Bob (also represented by a fearsome armor-plated commando) about the future of books. The effect is truly bizarre.

The show was taped in a studio, with Bob and Damian (played by director Chris Burke), controllers in hand, seated in front of an Xbox console. Totally abandoning the story line of the game, the two avatars move through the surreal landscape – part derelict Soviet steel mill, part remote desert island – as though simply going for a stroll in the park. All their meanderings are recorded through a video feed and edited later on. Periodically, the conversation is interrupted by unfriendly fire from other online gamers unaware that a more civil interaction is taking place in the forbidding combat terrain. Damian has to deal with these intrusions, casually lobbing a grenade mid-sentence, or swooping across several hundred yards of game space to decapitate an assailant, swooping back to catch the end of Bob’s remark. It’s quite entertaining: the incongruousness of the conversation within the alien landscape of the game, the sudden bursts of violence. It reminds me a bit of Space Ghost Coast to Coast, which turned an old Hanna Barbera cartoon character into a talk show host with real celebrity guests. In the case of Spartan Life, there’s something weirdly logical about placing a conceptual conversation about the future in the future. A nice expressionistic touch.

The show fits into a recently emerged genre of films set in video game environments, known as “Machinima.” Most of the Machinima films I’ve seen are best described as surreal sitcoms – short episodes commenting on the inherent strangeness of video game worlds. The characters are often in the midst of existential crisis, asking “what am I doing here?” Like certain other genres (say, musicals), video games can appear comically absurd by adding just a small dose of reality. So far, Machinima has played in this territory, floating banal chit chat into the hyper-violent game worlds, finding humor in juxtaposition. Other games, like the Sims, offer their own possibilities for comical remixing. It’ll be interesting to see if the genre matures beyond this. By conducting real interviews, often with people unfamiliar with the game environment, This Spartan Life introduces a nice element of surprise.

The show fits into a recently emerged genre of films set in video game environments, known as “Machinima.” Most of the Machinima films I’ve seen are best described as surreal sitcoms – short episodes commenting on the inherent strangeness of video game worlds. The characters are often in the midst of existential crisis, asking “what am I doing here?” Like certain other genres (say, musicals), video games can appear comically absurd by adding just a small dose of reality. So far, Machinima has played in this territory, floating banal chit chat into the hyper-violent game worlds, finding humor in juxtaposition. Other games, like the Sims, offer their own possibilities for comical remixing. It’ll be interesting to see if the genre matures beyond this. By conducting real interviews, often with people unfamiliar with the game environment, This Spartan Life introduces a nice element of surprise.

It’s hard for us more traditional readers to grapple with the significance of video games. During the interview, Bob muses about what it will be like to walk around inside a book. What if other readers are interrupting or joining in the story you are reading? I grew up playing linear 2-D games like Super Mario Bros. and Castlevania. By the time the next generation of game systems was hitting the market with their new immersive 3-D narratives, my gaming habit had tapered off. But increasingly, kids are growing up with the expectation that narrative worlds (like books) will be interactive, multidirectional, and almost hallucinogenically real. There is the familiar complaint that younger generations have short attention spans, but the evidence offered by gaming suggests the opposite. While many kids may indeed have short attention spans for traditional media like books and certain kinds of films, they are perfectly capable of spending long stretches of time in complex game environments that combine stories with problem and puzzle solving, and that allow them to engage with peers within the game space. This is territory explored by Steven Johnson’s new book, which I have yet to pick up. But I’ll end with an amusing quote from his blog that I posted back in April when the book was coming out. It imagines what might have been society’s response if video games were in fact the older invention and books the dangerous new toy.

Reading books chronically under-stimulates the senses. Unlike the longstanding tradition of gameplaying–which engages the child in a vivid, three-dimensional world filled with moving images and musical soundscapes, navigated and controlled with complex muscular movements–books are simply a barren string of words on the page. Only a small portion of the brain devoted to processing written language is activated during reading, while games engage the full range of the sensory and motor cortices.

Books are also tragically isolating. While games have for many years engaged the young in complex social relationships with their peers, building and exploring worlds together, books force the child to sequester him or herself in a quiet space, shut off from interaction with other children. These new ‘libraries’ that have arisen in recent years to facilitate reading activities are a frightening sight: dozens of young children, normally so vivacious and socially interactive, sitting alone in cubicles, reading silently, oblivious to their peers.

Many children enjoy reading books, of course, and no doubt some of the flights of fancy conveyed by reading have their escapist merits. But for a sizable percentage of the population, books are downright discriminatory. The reading craze of recent years cruelly taunts the 10 million Americans who suffer from dyslexia–a condition didn’t even exist as a condition until printed text came along to stigmatize its sufferers.

But perhaps the most dangerous property of these books is the fact that they follow a fixed linear path. You can’t control their narratives in any fashion–you simply sit back and have the story dictated to you. For those of us raised on interactive narratives, this property may seem astonishing. Why would anyone want to embark on an adventure utterly choreographed by another person? But today’s generation embarks on such adventures millions of times a day. This risks instilling a general passivity in our children, making them feel as though they’re powerless to change their circumstances. Reading is not an active, participatory process; it’s a submissive one. The book readers of the younger generation are learning to ‘follow the plot’ instead of learning to lead.