“a navigational widget for switching between documents” (Wikipedia)

Tab is a simple word, but one that’s hard to pin down. It’s the first word that begins with “t” in the Oxford English Dictionary, but the OED admits that it’s not sure where the word originally comes from. Such a basic word has taken on a number of meanings over time: tabs that stick out of things or clothing, tabs as a control surface on an airplane. Colorful slang tabs: cats, cigarettes, girls (in Australia, obsolete?), old women, a dose of LSD. There’s almost certainly a “tab” key on the keyboard in front of you, a holdover from the typewriter. And another new usage is probably in front of you right now: the tabs that are used in computer interfaces. The OED is not helpful for this, but Wikipedia comes in handy, suggesting that the tabs that we see in software today can be traced back to IBM’s Common User Access guidelines, published in 1987. The tabbed browser goes back to 1994 according to the page on tabbed document interfaces, but didn’t reach the masses until Opera came out in 2000. Other web browsers soon followed, and now tabs are inescapable.

I’ve been thinking about my use of tabs, and in particular the way they’ve been affecting my reading behavior online. For the past year or so, my web browser has generally has around twenty tabs open, randomly arranged in three windows. I’m aided and abetted by some plugin to my browser that reopens it with the tabs it had when it was closed. There’s no real design in this: most of these pages are things that I’ve been meaning to deal with in some fashion, to read or to respond to in some way. In practice, this doesn’t happen: I’ve had at least four of my tabs open for most of the summer, hoping that some day I’ll get around to reading them. Soon, maybe. From time to time, I’ll have an organizational fit and move things over to del.icio.us, but it doesn’t happen as often as it should. As long as I don’t have thirty pages open, I feel that I’m reasonably on top of things. Safari crashes once in a while and resets things to zero, but I can usually pick up where I left off.

Even without tabs in my browser, concurrent reading seems the dominant reading behavior on computers. This is likely to grow more complex: my Bloglines account keeps me reading 180 different feeds from blogs around the web. Perhaps this doesn’t seem mind-boggling because we’re used to multitasking computers. Like most computer users, I’m constantly switching back and forth between my web browser, my email program, and whatever else I have open. All the messages in my email inbox don’t seem that dissimilar from the open tabs in my browser; my inbox is more of a mess than my browser. Some day I will clean up this virtual mess; for now, I will think about what it means to inhabit such a pigsty of reading.

What does it do? It becomes, like any behavior given enough time, normal. Nor is it a behavior that’s limited to reading online: I could make a pile of a dozen books that I’m in the middle of reading. I am, alas, easily distracted. Some of these books have been interrupted in their reading for so long that I’ll probably wind up starting over again – I have absolutely no memory of where I was in Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz when I set it aside last March to read something shorter. I do, I think, make it through most things eventually. It’s rare, however, that I finish a book without the interruption of another book; it’s rarer still that I finish a book without doing some sort of web reading while I’m reading it. Have I always been this way? Probably to some extent, though it certainly seems possible that using the web has fragmented my print reading. Certainly it’s not quite the same thing as the private utopia that Sven Birkerts, in The Gutenberg Elegies and elsewhere, has posited as the space inhabited by the reader of the print book. It’s the loss of this space – rather than the loss of the print book as an object – that Birkerts was concerned about. He might have a point there.

If something’s changed in the world of reading, it might be defined as a loss of linearity. Before the fall, people started reading books at the beginning, and kept on until they got to the end. Texts were read in series. Now, for better or for worse, we read things – books, texts, web pages – in parallel.

* * * * *

“7. tab.

1. A ‘tab’ (small square) of paper soaked in LSD acid.

2. A hard, long-distance march done with kit. Common in the Army and especially British SAS.

3. The place in Australia to bet. Totaliser Agency Board (TAB). Similar to Off Track Betting (OTB), but handle’s sports betting aswell.1. ‘You got any tab’s left.’

2. ‘We’ve still got a longtime left on this tab.’

3. ‘Let’s go to the TAB and lay down a few bets.’by Diego Jul 29, 2003.” (urbandictionary.com)

In thinking about the problem of what’s happening to reading now, it might be useful to go back a century, to the dawn of Cubism in painting. Braque and Picasso shattered the tradition of perspective, with its single vanishing point, in their attempts to paint subjects from multiple perspectives simultaneously. This was an enormous shift: what could be described under the rubric “painting” at the end of the twentieth century was extremely different from what a painting was at the start of the twentieth century. When perspective had been destroyed as a necessary concept in painting, the doors of what was admissible as visual arts were opened much wider.

In 1959, Brion Gysin was referring to this moment of rupture when he declared that writing was fifty years behind painting. Gysin made this argument while presenting the cut-up technique for generating texts, which reworked existing text to create something new. The cut-up technique wasn’t new: Tristan Tzara and the Dada poets had used it in the 1920s. Certainly fiction and poetry had been influenced by the breakdown of perspective in the visual arts: one of the hallmarks of High Modernism is a preoccupation with the fragmented. But Gysin did have a point and still does: the idea of literature that existed then was heavily dependent on the central concept of linearity. Many people haven’t adjusted to it: as Momus notes, there’s something reactionary in the cries for Dickens that have amplified in the past few years, a desire to skip what happened in the twentieth century, to go back to some bucolic ideal of the Victorian where A was A.

But what did happen? It’s hard to dispense with the linear in text: one letter follows the next, one word follows the next, one line follows the next, one page follows the next. There’s oral precedent: we can only say one word at a time. Aurally, things are different. When you go out into the street, you may hear many voices at once. It’s the feeling that the Futurist Umberto Boccioni tried to capture in his 1911 painting La strada entra nella casa, the street enters the house:

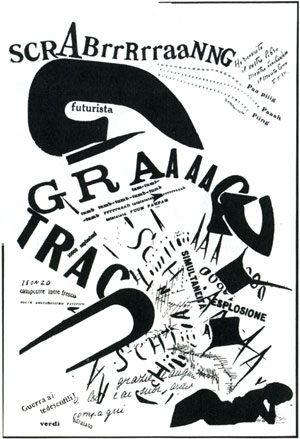

The leader of the Futurists was F. T. Marinetti, a poet, novelist, and manifesto-writer. At about the same time that Boccioni was painting streets entering the house, Marinetti was experimenting with parole in libertà (“words in freedom”), poetry made from words thrown about the page, poetry composed with type, lines, and the occasional drawing. Stéfane Mallarmé and Guillaume Apollinaire had experimented with placing words all over the page before him, but Marinetti innovated in his simultaneità, simultaneity. It’s impossible to read this poem in any definitive way: what order should these words and phrases be read in? The impression that Marinetti seemed to be trying to provoke was of a lot of people yelling at the same time, though the title of his poem suggests that it’s meant to be a letter that a gunner at the front sent back to his lover. But Marinetti’s mark-making doesn’t represent the words that the gunner says: instead, the words present the sounds that the gunner hears.

The leader of the Futurists was F. T. Marinetti, a poet, novelist, and manifesto-writer. At about the same time that Boccioni was painting streets entering the house, Marinetti was experimenting with parole in libertà (“words in freedom”), poetry made from words thrown about the page, poetry composed with type, lines, and the occasional drawing. Stéfane Mallarmé and Guillaume Apollinaire had experimented with placing words all over the page before him, but Marinetti innovated in his simultaneità, simultaneity. It’s impossible to read this poem in any definitive way: what order should these words and phrases be read in? The impression that Marinetti seemed to be trying to provoke was of a lot of people yelling at the same time, though the title of his poem suggests that it’s meant to be a letter that a gunner at the front sent back to his lover. But Marinetti’s mark-making doesn’t represent the words that the gunner says: instead, the words present the sounds that the gunner hears.

Marinetti came to a bad end: his enthusiasm for the excitement of modern life became love of the violence of war – as evidenced by the poem above – and he fell in with Mussolini and Fascism. The history of non-linearity in writing drops out at this point in history; probably in 1959 Gyson was unaware of Marinetti’s work.

But in the 1960s there was a veritable explosion of non-linearity. Julio Cortázar’s novel Hopscotch, published in 1963, is the best known novel to play with the form: Hopscotch presents one story when the first 56 chapters are read straight through, and another, slightly different story when the chapters are interleaved by the reader with the “expendable chapters” at the end of the book. This process is repeated in miniature in chapter 34 of the book, where the main character is reading an old novel and thinking about what he’s reading at the same time. (Click the image at left to see a readable version of a spread from this chapter.) Lines from the old novel are interleaved with Horacio’s thoughts as he’s reading, effectively presenting two different points of view at the same time. It’s more or less unreadable if you’re reading line by line; you have to skip lines and read the chapter twice, and it’s very hard to keep your place, as the two narratives constantly interpenetrate.

But in the 1960s there was a veritable explosion of non-linearity. Julio Cortázar’s novel Hopscotch, published in 1963, is the best known novel to play with the form: Hopscotch presents one story when the first 56 chapters are read straight through, and another, slightly different story when the chapters are interleaved by the reader with the “expendable chapters” at the end of the book. This process is repeated in miniature in chapter 34 of the book, where the main character is reading an old novel and thinking about what he’s reading at the same time. (Click the image at left to see a readable version of a spread from this chapter.) Lines from the old novel are interleaved with Horacio’s thoughts as he’s reading, effectively presenting two different points of view at the same time. It’s more or less unreadable if you’re reading line by line; you have to skip lines and read the chapter twice, and it’s very hard to keep your place, as the two narratives constantly interpenetrate.

At about the same time following the example of Marinetti and others, concrete poetry took off in the poetry world. There are plenty of similar experiments in other media: Andy Warhol’s film Chelsea Girls (1966) which presents two films side by side comes to mind. (A snippet can be viewed here.) Lou Reed was probably thinking of Chelsea Girls when he composed “The Murder Mystery”, a track from 1968 by the Velvet Underground. Ostensibly this song presents a story split into two halves, intoned by different members of the band into the left and right channels. With headphones, it can be deciphered as a narrative; played out loud, you can hear people talking, but you can’t understand what’s being said.

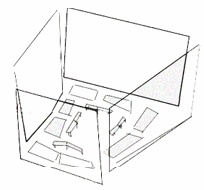

The experimental British novelist B. S. Johnson tried to achieve the same simultaneity in his novel House Mother Normal (1971), which presents the goings-on of a nursing home inhabited by residents with various degrees of consciousness and an abusive House Mother supervising them. Johnson presents nine narratives, each twenty pages long; each takes place simultaneously and at the same rate, so that the events on page 13 (shown above; click to enlarge) effectively happen nine times over, presented by nine different views. What’s actually happening in the time covered by House Mother Normal becomes more clear as the reader reads more of the narratives: no one consciousness is enough to present it. It’s an interesting presentation – like a musical score for text – and it works particularly well to humanely describing subjects who are not as mentally capable as we might expect narrators to be. But Johnson couldn’t entirely manage to escape the essentially linearity of text. What he’s found, as the monstrous House Mother explains at the end, when Johnson allows her to break character, is a way to create “a diagram of certain aspects of the inside of his skull” – perspective turned inside out.

* * * * *

“tab, sb. 5 Typewriting and Computing. [Abbrev. of TABULATOR b., TABULAR a., etc.] A tabulator (key); a tabular stop, used to preset the movement of the carriage, cursor, etc., under the direction of the tabulator.” (Oxford English Dictionary)

The TAB key is on the computer keyboard because it was on the typewriter keyboard. When you press the TAB key on a typewriter, the carriage advances forward. TAB does that on a computer sometimes – when you’re editing text, maybe – but this use of tabbing forward in text has never really felt at home on a computer, and it increasingly seems lost in the new digital world. Start typing paragraphs in Microsoft Word and it will automatically indent text for you. Pressing TAB to try to indent a new paragraph in a text editing window in a browser – a blog comment field, for example – and your cursor will move to some other text window or a button. TAB now moves between things, rather than advancing forward. Text on computers works in parallel rather than in series.

The Unfortunates (1969) is B. S. Johnson’s most notorious novel, if, perhaps, not the most widely read. It’s a book-in-a-box. It’s not the first novel to come in a box – Marc Saporta’s Composition No. 1, published in 1962, beat him by a few years, and was astoundingly translated from French to English as well. Composition No. 1 is a fairly standard detective story, which happens to have been broken up into pages which can be read in any order. One learns that crime is confusing and that in the end we don’t know anything about anything, which makes it an unsatisfying book. Johnson’s book is a bit more complex. Rather than dissociated pages, it’s a collection of little pamphlets, a couple of pages long each; it can’t be read in any order, as there’s a first and a last pamphlet that are to be read first and last. The narrative that emerges is of a sportswriter who’s covering a soccer match in a city he hasn’t been to in years; the last time he was there was with a friend who died of cancer. (Johnson erred on the side of the morbid.) The pamphlets are scattered memories of the past, a past that can’t be recovered or reconstructed. Cancer is senseless; a linear narrative, Johnson is suggesting, could only pretend to reason with it. Thus texts that can never fully be in sequence because there is no sequence.

There’s something here that’s similar, I think, to one of the issues that came up during the Gamer Theory experiment. Gamer Theory, as presented online, had an interface that suggested a deck of cards; the table of contents presented the chapters in such as way that one might be led to believe that one could start reading the book anywhere. This was not actually the case: McKenzie Wark’s book, despite its aphoristic style, does contain a linear argument which proceeds through the chapters. Though it did look like a deck of cards, it was not made to be shuffled like a deck of cards. In a sense, it was an old-fashioned book. But what it found online were new-style readers: readers who pick through the book to find things they were interested in, rather than readers who read the book through, attentive to the arc of its argument. Readers like me, who keep tabs open forever.

This isn’t, for what it’s worth, a flaw specific to Gamer Theory: this seems to be an issue with most texts designed for electronic reading. Almost all assume that they’re the only text being read – you could trace this back to CD-ROMs, if not further – as if the text were being read in a kiosk. (An interesting exception might be games, if you want to see games as texts, though I’ll leave that as an argument for the reader to make.) The choose-your-own-adventure model of hypertext suffers from this as well; though Hopscotch is often pointed to as a predecessor to hypertext, Cortázar’s book isn’t so much a garden of forking paths as two texts meant to be read in parallel.

I’m not suggesting that the serial nature of Gamer Theory is a flaw in either it as a book or it as an experiment, but it does give one pause. Could a book like Gamer Theory be constructed that’s not dependent upon a linear argument? A book designed to be read in tabs, in parallel with other texts? A book designed for the way we read now? There’s precedent, if we look in the right places: consider Wittgenstein, for example. The great work of Wittgenstein’s early philosophy, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, is structured in a numbered outline, carefully leading the reader down the path of his argument. Wittgenstein’s other great work is the Philosophical Investigations, takes the form of a series of sections. The sections are numbered but this is more for ease of reference than anything else; each is relatively self-contained. Each is designed to be read in isolation, but taken together they present a broad field of argument. The lack of rigorous structure in the Philosophical Investigations compared to the Tractatus doesn’t mean that the later work is simpler; it’s a more complex, nuanced argument. Reading in parallel doesn’t need to be a dumbed-down version of sequential reading, as we might imagine it to be: there are more possibilities.

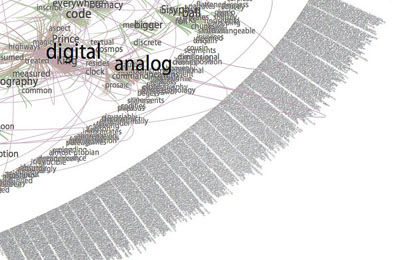

Monkeybook is an occasional series of new media evenings hosted by the Institute for the Future of the Book at Monkeytown, Brooklyn’s premier video art venue. For our second event, we are thrilled to present brilliant interaction designer, friend and collaborator W. Bradford Paley, who will be giving a live tour of his work on four screens. Next Monday, May 7. New Yorkers, save the date!

Monkeybook is an occasional series of new media evenings hosted by the Institute for the Future of the Book at Monkeytown, Brooklyn’s premier video art venue. For our second event, we are thrilled to present brilliant interaction designer, friend and collaborator W. Bradford Paley, who will be giving a live tour of his work on four screens. Next Monday, May 7. New Yorkers, save the date!

How can we ‘see’ a written text? Do you have a new way of visualizing writing on the screen? If so, then McKenzie Wark and the Institute for the Future of the Book have a challenge for you. We want you to visualize McKenzie’s new book, Gamer Theory.

How can we ‘see’ a written text? Do you have a new way of visualizing writing on the screen? If so, then McKenzie Wark and the Institute for the Future of the Book have a challenge for you. We want you to visualize McKenzie’s new book, Gamer Theory.