After enduring a weeks-long PR pummeling for its dealings in China, Google is hard at work to improve its image in the world, racking up some points for good after slipping briefly into evil. Recently they launched Google.org: a website for the Google Foundation, the corporation’s philanthropic arm and central office of evil mitigation. Paying a visit to the site, the disillusioned among us will be pleased to find that the foundation is already sponsoring a handful of worthy initiatives, along with a grants program that donates free web advertising to nonprofit organizations. And just in case we were concerned that Google might not apply its techno-capitalist wizardry to altruism as zealously as to making profit, they just announced today they’ve named a new director for the foundation by the name of — no joke — Dr. Brilliant. So it seems the world is in capable hands.

One project in particular caught my eye in light of recent discussions about screen-based reading and genre-blending visions of the book. Planet Read is an organization that promotes literacy in India through Same Language Subtitling — a simple but apparently effective technique for building basic reading skills, taking popular visual entertainment like Bollywood movies and adding subtitles in English and Hindi along the bottom of the screen. A number of samples (sadly no Bollywood, just videos or photo montages set to Indian folk songs) can be found on Google Video. Here’s one that I particularly liked:

Watching the video — managing the interplay between moving text and moving pictures — I began to wonder whether there are possibly some clues to be mined here about the future of reading. Yes, Planet Read is designed first and foremost to train basic alphabetic literacy, turning a captive audience into a captive classroom. But in doing so, might it not also be nurturing another kind of literacy?

The problem with contemporary discussions about the future of the book is that they are mired — for cultural and economic reasons — in a highly inflexible conception of what a book can be. People who grew up with print tend to assume that going digital is simply a matter of switching containers (with a few enhancements thrown in the mix), failing to consider how the actual content of books might change, or how the act of reading — which increasingly takes place in a dyanamic visual context — may eventually demand a more dynamic kind of text.

Blurring the lines between text and visual media naturally makes us uneasy because it points to a future that quite literally (for us dinosaurs at least) could be unreadable. But kids growing up today, in India or here in the States, are already highly accustomed to reading in screen-based environments, and so they probably have a somewhat different idea of what reading is. For them, text is likely just one ingredient in a complex combinatory medium.

Another example: Nochnoi Dozor (translated “Night Watch”) is a film that has widely been credited as the first Russian blockbuster of the post-Soviet era — an adrenaline-pumping, special effects-infused, sci-fi vampire epic made entirely by Russians, on Russian soil and on Russian themes (it’s based on a popular trilogy of novels). When it was released about a year and a half ago it shattered domestic box office records previously held by Western hits like Titanic and Lord of the Rings. Just about a month ago, the sequel “Day Watch” shattered the records set by “Night Watch.”

While highly derivative of western action movies, Nochnoi Dozor is moody, raucous and darkly gorgeous, giving a good, gritty feel of contemporary Moscow. Its plot grows rickety in places, and sometimes things are downright incomprehensible (even, I’m told, with fluent Russian), so I’m skeptical about its prospects on this side of the globe. But goshdarnit, Russians can’t seem to get enough of it — so in an effort to lure American audiences over to this uniquely Russian gothic thriller, start building a brand out of the projected trilogy (and presumably pave the way for the eventual crossover to Hollywood of director Timur Bekmambetov), Fox Searchlight just last week rolled the film out in the U.S. on a very limited release.

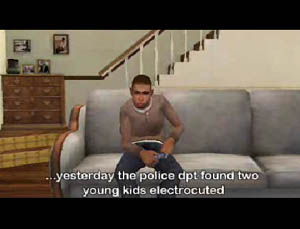

What could this possibly have to do with the future of reading? Well, naturally the film is subtitled, and we all know how subtitles are the kiss of death for a film in the U.S. market (Passion of the Christ notwithstanding). But the marketers at Fox are trying something new with Nochnoi Dozor. No, they weren’t foolish enough to dub it, which would have robbed the film of the scratchy, smoke-scarred Moscow voices that give it so much of its texture. What they’ve done is played with the subtitles themselves, making them more active and responsive to the action in the film (sounds like some Flash programmer had a field day…). Here’s a description from an article in the NY Times (unfortunately now behind pay wall):

…[the words] change color and position on the screen, simulate dripping blood, stutter in emulation of a fearful query, or dissolve into red vapor to emulate a character’s gasping breaths.

And this from Anthony Lane’s review in the latest New Yorker:

…the subtitles, for instance, are the best I have encountered. Far from palely loitering at the foot of the screen, they lurk in odd corners of the frame and, at one point, glow scarlet and then spool away, like blood in water. I trust that this will start a technical trend and that, from here on, no respectable French actress will dream of removing her clothes unless at least three lines of dialogue can be made to unwind across her midriff.

It might seem strange to think of subtitling of foreign films as a harbinger of future reading practices. But then, with the increasing popularity of Asian cinema, and continued cross-pollination between comics and film, it’s not crazy to suspect that we’ll be seeing more of this kind of textual-visual fusion in the future.

Most significant is the idea that the text can itself be an actor in a perfomance: a frontier that has only barely been explored — though typography enthusiasts will likely pillory me for saying so.