I want to tell you about one scene in a wonderful documentary, DOC, that just opened the Margaret Mead Film Festival at the Museum of Natural History in New York. Doc Humes was the founder of the Paris Review. Made by his daughter, Immy, the film follows Immy as she tries to uncover the layers of her father’s complex life. At one point she finds out that he made a feature film and she tries to find the footage. She gets a tip that Jonas Mekas may have a copy at Anthology Film Archives in the east village in New York. She goes to visit Mekas and takes her camera. Mekas takes her into the vast underground storeroom and points at row after row after row after row of film cans. The point of the shot is that looking for the film on these shelves — even if it were known to be here, which it isn’t — is a hopeless task. Nothing seems to be marked; there is no order. Rather than a salvation for the rich film culture that came out of NY in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, it seems that the Anthology Film Archive may become a graveyard.

Seeing this made me wonder about the decisions we make as a society about what to keep and what not to keep. There may be important film in those cans or there may not be. How do we decide whether to gather the resources to find out?

Category Archives: film

new love meetings: “il primo film girato con un telefonino”

Leafing through my hardcopy of the September/October edition of Filmcomment, published by the Film Society of Lincoln Center, I came across a mini-review of “New Love Meetings,” co-directed by Marcello Mencarini and Barbara Seghezzi. First featured in The Guardian Unlimited, this story was newsworthy because this film is reportedly the first feature (93 minutes) entirely shot with a cell phone. “New Love Meetings” was filmed in MPEG4 format using a Nokia N90, and follows on Pasolini’s 1965 documentary “Love Meetings,” in which he interviewed Italian men and women about their views on sex in postwar Italy. Mencarini and Seghezzi used cell phones to interview about 700 people at regular meeting places such as bars, markets, the beach, etc.

Leafing through my hardcopy of the September/October edition of Filmcomment, published by the Film Society of Lincoln Center, I came across a mini-review of “New Love Meetings,” co-directed by Marcello Mencarini and Barbara Seghezzi. First featured in The Guardian Unlimited, this story was newsworthy because this film is reportedly the first feature (93 minutes) entirely shot with a cell phone. “New Love Meetings” was filmed in MPEG4 format using a Nokia N90, and follows on Pasolini’s 1965 documentary “Love Meetings,” in which he interviewed Italian men and women about their views on sex in postwar Italy. Mencarini and Seghezzi used cell phones to interview about 700 people at regular meeting places such as bars, markets, the beach, etc.

Cell-phone short movies have become ubiquitous in the Internet, and they have achieved some visibility in film festivals, but Mencarini and Seghezzi’s premise is that even though they asked very much the same questions that Pasolini posed, the results of their film are marked by the medium they used to shoot it. The use of a cell phone, an instrument that belongs to people’s daily lives, produced an intimacy absent in Pasolini’s movie. In a way, the filmmakers were very much like normal people using their cell phones to preserve an instant. This leads people to be more spontaneous and open, making the dialogue more like a chat than an interview.

This technique underscores the fact that today, memories can be captured and disseminated instantly thanks to the nature of our networked world, and that the way we preserve them is not the realm of books, not even of traditional films. Memory is instant, intimacy is public, and we communicate more readily than ever before. People have used stone, scrolls, print, wax cylinders, film, and tape, to preserve and disseminate memories, “New Love Meetings” is yet another example of the permeability and plasticity of mediums within which we move today. We cannot apply traditional, orthodox aesthetic values to the hybrid products of the moment. Experimentation doesn’t follow a master plan.

reading buildings

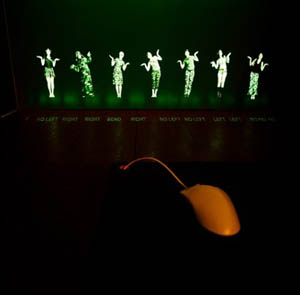

On Monday, Adriene Jenik, who is Associate Professor of Computer & Media Arts at UC San Diego, stopped by for what turned into an interesting discussion on the future of libraries. Adriene is a telecommunications media artist who has experimented extensively in virtual performance with projects like Desktop Theater and SPECFLIC, an ongoing “speculative distributed cinema project.”

More recently, she wrote and produced SPECFLIC 2.0, which explores the intersection of digital media, books, and reading. With the help of a large network of collaborating artists, Jenik transformed the Martin Luther King Library in San Jose into a one night only vision of the future called the InfoSphere, where a computerized reference librarian called The Infospherian provides an interface to all the bits of information what anyone might need, and is in charge of issuing and enforcing reading licenses to the public.

Before the group got to discussing how libraries where changing, Adriene and I first discussed how neighborhoods and cities develop; the way growth is encouraged and discouraged in certain areas, and of those who benefit from seeing either scenario play out.

As in the discussion we had about neighborhoods, I am ambivalent towards the way libraries are changing. People use search engines to find information quickly and are less frequently doing research in libraries. In fact, even in libraries computer labs tend to be the most populous rooms. The act of looking through physical books lends itself well to serendipitous discoveries, and while I agree that many of these kinds of experiences may be lost, it’s hard to really know for sure what is gained and what is lost when you’re in the midst of change.

For better or worse, as a tool, the library, as we know it today, appears to have lived out it’s life. In the future, the idea of a library as a museum, as opposed to an active location like a park makes a lot more sense to me. Something will be lost with the transition, that is for sure, and as much of it as possible should be preserved, but it’s hard to see today’s library being able to compete with the technologies of the future in the same way.

What I find bizarre about all this is that when you walk into a Barnes & Noble all the seats are taken, so it seems that “reading buildings” of some sort have some demand. Maybe it’s the social setting or maybe it’s the Starbucks. Actually, that could be the future of the library: a big empty building that people bring their electronic books to so that they can read and drink their coffee in a social setting… quietly.

“No analog book allowed inside library. Please digitize your analog book at the door.”

what’s important to save

Rick Prelinger and Megan Shaw visited for lunch earlier in the week and gave us a preview of the very interesting presentation they made later that day about the SF-based Prelinger Library . Beginning in the 70s Rick started collecting film and video that no one else seemed to want — industrials (e.g. GM’s worldfair and auto show films), educational films (think “how to be popular”, “how to be a good citizen” and how to make the perfect jelly), and filmed advertisements to be shown in movie theaters and early TV. Rick’s contention, as the first serious media archaeologist, was that these films that no one intended to be saved or seen again — ephemeral films — often provided much more insight about howsociety has evolved in the twentieth century than the big budget hollywood films which tend to be more self-conscious and indirect.

Below are a few clips from some of my favorites. the clip from “A Date With Your Family” contains one of the scariest moments i’ve ever encountered in film, when at the end of the clip, the narrator remarks as “father” returns from his day at the office . . . . that “these boys greet their dad AS THOUGH they are genuinely glad to see him, AS THOUGH they had really missed being away from him during the day . . . ” In the second clip, “A Young Man’s Fancy,” the daughter in a pensive mood says “I was just thinking” and the mother says incredulously, “thinking?” as if that’s the most outlandish thing she can imagine her daughter doing.

A few years ago, the Library of Congress, recognizing the inestimable value of Rick’s collection, bought the whole kit and caboodle. Since then, Rick and his partner, Megan Shaw have turned their attention to print, building a library of unusual books, periodicals and print ephemera; e.g. an invaluable collection of ESSO’s state maps from the fities that favors serendipitous browsing and remix. (the cover of the ESSO map below depicts a young boy being introduced by his dad to the wonders of nuclear fusion).

The following is from the description on the library’s website:

Though libraries live on (and are among the least-corrupted democratic institutions), the freedom to browse serendipitously is becoming rarer. Now that many research libraries are economizing on space and converting print collections to microfilm and digital formats, it’s becoming harder to wander and let the shelves themselves suggest new directions and ideas. Key academic and research libraries are often closed to unaffiliated users, and many keep the bulk of their collections in closed stacks, inhibiting the rewarding pleasures of browsing. Despite its virtues, query-based online cataloging often prevents unanticipated yet productive results from turning up on the user’s screen. And finally, much of the material in our collection is difficult to find in most libraries readily accessible to the general public.

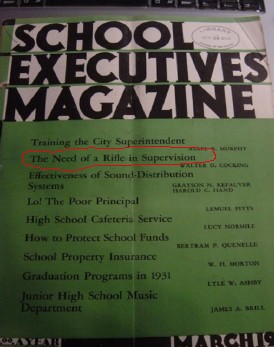

While listening to Rick and Megan’s talk i had a minor AHA moment. a lot of our skepticism and concern about Google centers on the inherent dangers of a private company being entrusted with the care and feeding of our increasingly digitize culture. When Rick and Megan showed the cover of School Executives, a journal from the 40s, which featured an article on the value of teachers toting guns to enforce classroom discipline, i realized that Google’s digitization efforts focus entirely on codex books (maybe to be extended to periodicals that libraries have bothered to store). but the invaluable materials that might be called “print-based” ephemera — pamphlets, marketing materials, off-beat journals, zines etc. — will be absent in the future. The sad thing about this, as we know from Rick’s ephemeral film collection, is that often these pieces that were never meant to survive tell us more about how our culture evolved and how we’ve ended up where we are, than many self-conscious efforts conceived with permanence in mind.

documentary licensed through creative commons to play in second life

Route 66: An American Bad Dream is an independent documentary film starring three Germans road tripping across the legendary US highway. What makes this film notable is that they released the film under the Creative commons license. Also, it had its premiere in the virtual world of Second Life on Aug 10th. The success of that showing prompted them to host an additional viewing this Thursday August 31 at 4PM SL in Kula 4, which will be presented by its creator Gonzo Oxberger. In the Open Source spirit of this project, they are making the video and audio project files available to anyone with a serious interest in remixing the film.

incredible ulysses animation

Alex Itin, our ever-astonishing resident artist/blogger, has been playing around with viral video outlets like YouTube, Google Video, Vimeo and MySpace, embedding movies on his site and re-mounting some of his older film projects, which were previously too cumbersome for quick-and-dirty webcasting.

The following (originally posted here) is a short animated riff on Joyce’s Ulysses, in which actual pages from the book serve as frames, with figures painted over text. Joyce himself provides the vocal track. The drawings and sound apparently were not synched, which at times is hard to believe since they can be strikingly consonant.

NSFW!

Alex has been painting on books for years, exploring a kind of palimpsest style — old, yellowed texts or roadmaps like the walls of a decaying city, against which sinewy, calligraphic figures move. Some of his mixed media works, like Odd City (re-mounted recently on the blog as an animated GIF) have involved the flipping of pages, which yields a crude filmic effect. “You Cities” works on a grander scale, opening up new dimensions on the 2-D page. You find yourself pulled into a visual stream of consciousness.

art as politics

The term “political art” has implications that might well deter people from viewing it, especially here where the political is regarded as unaesthetic. It is sad that when an American artist makes “political art” it becomes news. This has been the case with the presence of political films in Cannes, as chronicled by A. O. Scott in the New York Times. He makes a parallel with the 60’s as a golden age of filmmaking, and in particular the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, where the artistic and the political were absolutely interconnected. To say that the problems we are facing today are less significant than those of the 60’s is to exchange lack of hope for the authentic belief in change that permeated that era.

The big difference today is that communications are immediate and indispensable, but that their ubiquity has also numbed us. War and catastrophe as spectacle have always fed the public imagination, but today fiction and fact, reality and artifice, have collapsed into yet another consumer product. On the other hand, the availability of affordable technology has made photography, video and filmmaking accessible to many. Now, it is possible to see interesting and good quality pieces from places far away from the established centers of film production. Cannes is still the favorite showplace of international cinema, but it doesn’t mean that many movies that make it there ever go beyond the art houses. So, the presence of Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth,” Richard Linklater and Eric Schlosser’s “Fast Food Nation” or Linklater’s “A Scanner Darkly” and Richard Kelly’s “Southland Tales” are news not because they are represented in Cannes but because they tell stories based on present circumstances without fear of being “political.”

Holland Cotter the art critic of The New York Times reviews some current exhibitions that make political commentary noting that in 21st-century America political art is not “protest art” but a mirror. But, what else is art, past and present, than a mirror that uncannily shows political realities? The fact that many artists insist on looking at their belly buttons instead of at the world, is in itself a political commentary of the times. Cotter reviews Harrell Fletcher’s http://www.harrellfletcher.com/# show at White Columns, images from a museum in Ho Chi Minh City, as a horrific document of the Vietnam War. Jenny Holzer at Cheim and Read shows a series of silk screens of declassified documents related to Abu Ghraib, which are faithful to each official word with the exception of their magnification, thus becoming a commentary on our nation’s violence.

from Archive — Jenny Holzer

Coco Fusco‘s video, “Operation Atropos,” documenting the training on interrogation and resistance program she and six women went through in the woods of the Poconos, offers a political glance at the methods of physical and mental persuasion. Apart from the obviously political, the viewer realizes that this program, run by former members of the CIA, has been conceived for the private sector.

Operation Atropos

Cotter concludes his article asking, “So what kind of political art is this? It isn’t moralizing or accusatory. It’s art for a time when play-acting and politics seem to be all but indistinguishable.” They are.

It is always enormously refreshing to visit the art galleries, and to be reminded that many artists in many places, perhaps because they are faced with stark realities on a daily basis, have indeed a lot to comment. The Asian Contemporary Art Week (5/22-5/27) was one of those occasions (and still is since many galleries will continue displaying Asian art for a few more weeks.) Shilpa Gupta‘s interactive video environments at Bose Pacia offer a comment on power, militarism and imperialism. In one of the pieces the viewer sees a bucolic landscape in Kashmir and as s/he touches the screen military guards appear. Truth is indeed a fragile and many times deceiving construction.

Untitled, 2005 — Shilpa Gupta

Tejal Shah‘s video installation at Thomas Erben presents the transgender community in India from within, a reality that is equally painful and celebratory. At the Sculpture Center, as part of the Grey Flags exhibition, there is a film by Apichatpong Weerasethakul the Thai filmmaker whose fresh approach to reality has taken him to use non-professional actors and improvised dialogue, offering a sober and supetcharged vision of reality in Thailand. Tilton Gallery brings together 34 contemporary Chinese artists entitled “Jiang Hu” whose literal meaning is “rivers and lakes” but that metaphorically means a place removed from the mainstream. In medieval literature it means a realm inhabited by outsiders, monks, fortune-tellers and artists who had magical powers. In the context of this exhibit that shows an interesting and disparate group, “Jiang Hu” evokes a complex reality: China an outsider within the global world.

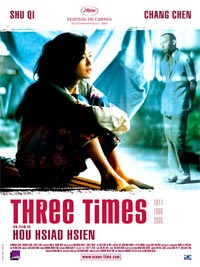

love through networked screens

This past weekend, I saw a remarkable film: “Three Times,” by Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. It’s a triptych on love set in Taiwan in three separate periods — 1966, 1911, and 2005 — each section focusing on a young man and woman, played by the same actors. Hou does incredible things with time. Each of the episodes, in fact, is a sort of study in time, not just of a specific time in history, but in the way time moves in love relationships. The opening shots of the first episode, “A Time for Love,” announce that things will be operating in a different temporal register. Billiard balls glide across a table. You don’t yet understand the rules of the game that is being played. Characters gradually emerge and the story unfolds through strange compressions and contractions of time that comprise a weird logic of yearning.

This past weekend, I saw a remarkable film: “Three Times,” by Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. It’s a triptych on love set in Taiwan in three separate periods — 1966, 1911, and 2005 — each section focusing on a young man and woman, played by the same actors. Hou does incredible things with time. Each of the episodes, in fact, is a sort of study in time, not just of a specific time in history, but in the way time moves in love relationships. The opening shots of the first episode, “A Time for Love,” announce that things will be operating in a different temporal register. Billiard balls glide across a table. You don’t yet understand the rules of the game that is being played. Characters gradually emerge and the story unfolds through strange compressions and contractions of time that comprise a weird logic of yearning.

This is the first of Hou’s films that I’ve seen (it’s only the second to secure an American release). I was reminded of Tarkovsky in the way Hou uses cinema to convey the movement of time, both across the eras and within individual episodes. There’s much to say about this film, and I hope to see it again to better figure out how it does what it does. The reason I bring it up here is that the third story — “A Time for Youth,” set in contemporary Taipei — contains some of the most profound and visually arresting depictions of the mediation of intimate relationships through technology that I’ve ever seen. Cell-phones and computers have been popping up in movies for some time now, usually for the purposes of exposition or for some spooky haunted technology effect, like in “The Matrix” or “The Ring.” In “Three Times,” these new modes of contact are probed more deeply.

The story involves a meeting of an epileptic lounge punk singer and an admiring photographer, while the singer’s jilted female lover lurks in the margins.  Hou weaves back and worth between intense face-to-face meetings and asynchronous electronic communication. At various times, the screen of the movie theater (the IFC in Greenwich Village) is completely filled with an extreme close-up of a cell-phone screen or a computer monitor, the text of an SMS or email message as big as billboard lettering. The pixelated Chinese characters are enormous and seem to quiver, or to be on the verge of melting. A cursor blinking at the end of an alleged suicide note typed into a computer is a dangling question of life and death, or perhaps just a sulky dramatic gesture.

Hou weaves back and worth between intense face-to-face meetings and asynchronous electronic communication. At various times, the screen of the movie theater (the IFC in Greenwich Village) is completely filled with an extreme close-up of a cell-phone screen or a computer monitor, the text of an SMS or email message as big as billboard lettering. The pixelated Chinese characters are enormous and seem to quiver, or to be on the verge of melting. A cursor blinking at the end of an alleged suicide note typed into a computer is a dangling question of life and death, or perhaps just a sulky dramatic gesture.

What’s especially interesting is that the most expressive speech in “A Time for Youth” is delivered electronically. Face-to-face meetings are more muted and indirect. There’s an eerie episode in a nightclub where the singer is performing on stage while the photographer and another man circle her with cameras, moving as close as they can without actually touching her, shooting photos point blank.

But it was the use of screens that really struck me. By filling our entire field of vision with them — you almost feel like you’re swimming in pixels — Hou conveys how tiny channels of mediated speech can carry intense, all-consuming feeling. The weird splotchiness of digital text at close range speaks of great vulnerability. Similarly, the revelation of the singer’s epilepsy is not through direct disclosure, but happens by accident when she leaves behind a card with instructions for what to do in case of a seizure, after spending the night at the photographer’s apartment. This all strikingly follows up the previous episode, “A Time for Freedom,” which is done as a silent film with all the dialogue conveyed on placards.

It’s one of those things that suddenly you viscerally understand when a great artist shows you: how these technologies spin a web of time around us, sending voices and gestures across space instantly, but also placing a veil between people when they actually share a space. In many ways, these devices bring us closer, but they also fracture our attention and further insulate us. Never are you totally apart, but seldom are you totally together.

“Three Times” is currently out in a few cities across the US and rolling out progressively through June in various independent movie houses (more info here).

war machinima

Ray, Bob and I spent last week out in Los Angeles at our institutional digs (the Annenberg Center for Communication at USC), where we held a pair of meetings with professors from around the US and Canada to discuss various coups we are attempting to stage within the ossified realm of scholarly and textbook publishing. Following these, we were able to stick around for a fun conference/media festival organized by Annenberg’s Networked Publics project.

The conference was a mix of the usual academic panels and a series of curated mini-exhibits of “do-it-yourself” media, surveying new genres of digital folk art currently proliferating across the net such as political remix movies, anime music videos, “digital handmade” art projects (which featured the near and dear Alex Itin — happy birthday, Alex!), and of course, machinima: films made inside of video game engines.

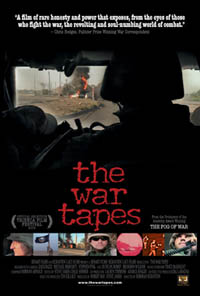

As we enjoyed this little feast of new media, I was vaguely aware that the Tribeca film festival was going on back in New York. As I casually web-surfed through one of the panels — in the state of continuous partial attention that is now the standard state of being all these networky conferences — I came across an article about one of the more talked about films appearing there this year: “The War Tapes.” Like Gunner Palace and Occupation Dreamland, “The War Tapes” is a documentary about American soldiers in Iraq, but with one crucial difference: all the footage was shot by actual soldiers.

As we enjoyed this little feast of new media, I was vaguely aware that the Tribeca film festival was going on back in New York. As I casually web-surfed through one of the panels — in the state of continuous partial attention that is now the standard state of being all these networky conferences — I came across an article about one of the more talked about films appearing there this year: “The War Tapes.” Like Gunner Palace and Occupation Dreamland, “The War Tapes” is a documentary about American soldiers in Iraq, but with one crucial difference: all the footage was shot by actual soldiers.

Back in 2004, director Deborah Scranton gave video cameras to ten members of the New Hampshire National Guard who were about to depart for a yearlong tour in Iraq. They went on to shoot a combined 800 hours of film, the pared-down result of which is “The War Tapes.” Reading about it, I couldn’t help but think that here was a case of real-life machinima. Give the warriors cameras and glimpse the war machine from the inside — carve out a new game within the game.

Granted, it’s a far from perfect analogy. Machinima involves a total repurposing of the characters and environment, foregoing the intended objectives of the game. In “The War Tapes,” the soldiers are still on their mission, still within the chain of command. And of course, war isn’t a video game. But isn’t it advertised as one?

Time Square, New York City (the military-entertainment complex)

There’s something undeniably subversive about giving cameras to GIs in what is such a thoroughly mediated war, a sort of playing against the game — if not of the game of occupation as a whole, then at least the game of spin. “I’m not supposed to talk to the media,” says one soldier to Steve Pink, one of the film’s main subjects, as he attempts to conduct an interview. To which Pink replies: “I’m not the media, dammit!”

In the clips I found on the film’s promotional site (the general release is later this summer), the overriding impression is of the soldiers’ isolation and fear: the constant terror of roadside bombs, frantic rounds fired into the green night-vision darkness, swaddled in helmets and humvees and hi-tech weaponry. It’s a frightening game they play. Deeply impersonal and anonymous, and in no way resembling the pumped-up, guitar-screeching game that the military portrays as war in its recruiting ads. This is the horrible truth at the bottom of the “Army of One” slogan: you are a lone digit in a massive calculation. Just pray you don’t become a zero.

Yet naturally, they find their own games to play within the game. One clip shows the tiny, gruesome spectacle of two soldiers, in a moment of leisure, pitting a scorpion against a spider inside a plastic tub, reenacting their own plight in the language of the desert.

At the Net Publics conference, we did see see one example of genuine machinima that made its own spooky commentary on the war: a hack of Battlefield 2 by Swedish game forum Snoken that brilliantly apes the now-famous Sony Bravia commercial, in which 250,000 colored plastic balls were filmed cascading through the streets of a San Francisco.

Here’s Battlefield:

And here’s the original Sony ad:

McKenzie Wark doesn’t address machinima in GAM3R 7H30RY (which launches in about a week), but he does discuss video games in the context of the “military entertainment complex”: the remaking of postmodern capitalist society in the image of the digital game, in which every individual is a 1 or a 0 locked in senseless competition for advancement through the levels, each vying to “win” the game:

The old class antagonisms have not gone away, but are hidden beneath levels of rank, where each agonizes over their worth against others in the price of their house, the size of their vehicle and where, perversely, working longer and longer hours is a sign of winning the game. Work becomes play. Work demands not just one’s mind and body but also one’s soul. You have to be a team player. Your work has to be creative, inventive, playful – ludic, but not ludicrous.

Video games (which can actually be won) are allegories of this imperfect world that we are taught to play like a game, as though it really were governed by a perfect (and perfectly fair) algorithm — even the wars that rage across its hemispheres:

Once games required an actual place to play them, whether on the chess board or the tennis court. Even wars had battle fields. Now global positioning satellites grid the whole earth and put all of space and time in play. Warfare, they say, now looks like video games. Well don’t kid yourself. War is a video game – for the military entertainment complex. To them it doesn’t matter what happens ‘on the ground’. The ground – the old-fashioned battlefield itself – is just a necessary externality to the game. Slavoj Zizek: “It is thus not the fantasy of a purely aseptic war run as a video game behind computer screens that protects us from the reality of the face to face killing of another person; on the contrary it is this fantasy of face to face encounter with an enemy killed bloodily that we construct in order to escape the Real of the depersonalized war turned into an anonymous technological operation.” The soldier whose inadequate armor failed him, shot dead in an alley by a sniper, has his death, like his life, managed by a computer in a blip of logistics.

How does one truly escape? Ultimately, Wark’s gamer theory is posed in the spirit that animates the best machinima:

The gamer as theorist has to choose between two strategies for playing against gamespace. One is to play for the real. (Take the red pill). But the real is nothing but a heap of broken images. The other is to play for the game (Take the blue pill). Play within the game, but against gamespace. Be ludic, but also lucid.

corporate creep

A short article in the New York Times (Friday March 31, 2006, pg. A11) reported that the Smithsonian Institution has made a deal with Showtime in the interest of gaining an “active partner in developing and distributing [documentaries and short films].” The deal creates Smithsonian Networks, which will produce documentaries and short films to be released on an on-demand cable channel. Smithsonian Networks retains the right of first refusal to “commercial documentaries that rely heavily on Smithsonian collection or staff.” Ostensibly, this means that interviews with top personnel on broad topics is ok, but it may be difficult to get access to the paleobotanist to discuss the Mesozoic era. The most troubling part of this deal is that it extends to the Smithsonian’s collections as well. Tom Hayden, general manager of Smithsonian Networks, said the “collections will continue to be open to researchers and makers of educational documentaries.” So at least they are not trying to shut down educational uses of the these public cultural and scientific artifacts.

Except they are. The right of first refusal essentially takes the public institution and artifacts off the shelf, to be doled out only on approval. “A filmmaker who does not agree to grant Smithsonian Networks the rights to the film could be denied access to the Smithsonian’s public collections and experts.” Additionally, the qualifications for access are ill-defined: if you are making a commercial film, which may also be a rich educational resource, well, who knows if they’ll let you in. This is a blatant example of the corporatization of our public culture, and one that frankly seems hard to comprehend. From the Smithsonian’s mission statement:

The Smithsonian is committed to enlarging our shared understanding of the mosaic that is our national identity by providing authoritative experiences that connect us to our history and our heritage as Americans and to promoting innovation, research and discovery in science.

Hayden stated the reason for forming Smithsonian Networks is to “provide filmmakers with an attractive platform on which to display their work.” Yet, it was clearly stated by Linda St. Thomas, a spokeswoman for the Smithsonian, “if you are doing a one-hour program on forensic anthropology and the history of human bones, that would be competing with ourselves, because that is the kind of program we will be doing with Showtime On Demand.” Filmmakers are not happy, and this seems like the opposite of “enlarging our shared understanding.” It must have been quite a coup for Showtime to end up with stewardship of one of America’s treasured archives.

The application of corporate control over public resources follows the long-running trend towards privatization that began in the 80’s. Privatization assumes that the market, measured by profit and share price, provides an accurate barometer of success. But the corporate mentality towards profit doesn’t necessarily serve the best interest of the public. In “Censoring Culture: Contemporary Threats to Free Expression” (New Press, 2006), an essay by André Schiffrin outlines the effects that market orientation has had on the publishing industry:

As one publishing house after another has been taken over by conglomerates, the owners insist that their new book arm bring in the kind off revenue their newspapers, cable television networks, and films do….

To meet these new expectations, publishers drastically change the nature of what they publish. In a recent article, the New York Times focused on the degree to which large film companies are now putting out books through their publishing subsidiaries, so as to cash in on movie tie-ins.

The big publishing houses have edged away from variety and moved towards best-sellers. Books, traditionally the movers of big ideas (not necessarily profitable ones), have been homogenized. It’s likely that what comes out of the Smithsonian Networks will have high production values. This is definitely a good thing. But it also seems likely that the burden of the bottom line will inevitably drag the films down from a public education role to that of entertainment. The agreement may keep some independent documentaries from being created; at the very least it will have a chilling effect on the production of new films. But in a way it’s understandable. This deal comes at a time of financial hardship for the Smithsonian. I’m not sure why the Smithsonian didn’t try to work out some other method of revenue sharing with filmmakers, but I am sure that Showtime is underwriting a good part of this venture with the Smithsonian. The rest, of course, is coming from taxpayers. By some twist of profiteering logic, we are paying twice: once to have our resources taken away, and then again to have them delivered, on demand. Ironic. Painfully, heartbreakingly so.