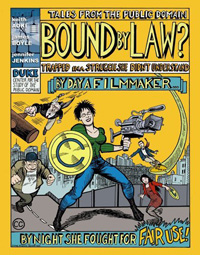

“The Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use,” by the Center for Social Media at American University is another work in support of fair-use practices to go along with the graphic novel “Bound By Law” and the policy report “Will Fair Use Survive?“.

“The Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use,” by the Center for Social Media at American University is another work in support of fair-use practices to go along with the graphic novel “Bound By Law” and the policy report “Will Fair Use Survive?“.

“Will Fair Use Survive” (which Jesse previously discussed) takes a deeper policy analysis approach. “Bound By Law” (also reviewed by me) uses an accessible tact to raise awareness in this area. Whereas, “The Statement of Best Practice” is geared towards the actual use of copyrighted material under fair use by practicing documentary filmmakers. It is an important compliment to the other works because the current confusion over claiming fair use has resulted in a chilling effect which stops filmmakers from pursuing projects which require (legal) fair use claims. This document give them specific guidelines on when and how they can make fair use claims. Assisting filmmakers in their use of fair use will help shift the norms of documentary filmmaking and eventually make these claims easier to defend. This guide was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation and Grantmakers in Film and Electronic Media.

Category Archives: fair_use

microsoft enlists big libraries but won’t push copyright envelope

In a significant challenge to Google, Microsoft has struck deals with the University of California (all ten campuses) and the University of Toronto to incorporate their vast library collections – nearly 50 million books in all – into Windows Live Book Search. However, a majority of these books won’t be eligible for inclusion in MS’s database. As a member of the decidedly cautious Open Content Alliance, Windows Live will restrict its scanning operations to books either clearly in the public domain or expressly submitted by publishers, leaving out the huge percentage of volumes in those libraries (if it’s at all like the Google five, we’re talking 75%) that are in copyright but out of print. Despite my deep reservations about Google’s ascendancy, they deserve credit for taking a much bolder stand on fair use, working to repair a major market failure by rescuing works from copyright purgatory. Although uploading libraries into a commercial search enclosure is an ambiguous sort of rescue.

open source DRM?

A couple of weeks ago, Sun Microsystems released specifications and source code for DReaM, an open-source, “royalty-free digital rights management standard” designed to operate on any certified device, licensing rights to the user rather than to any particular piece of hardware. DReaM (Digital Rights Management — everywhere availble) is the centerpiece of Sun’s Open Media Commons initiative, announced late last summer as an alternative to Microsoft, Apple and other content protection systems. Yesterday, it was the subject of Eliot Van Buskirk’s column in Wired:

Sun is talking about a sea change on the scale of the switch from the barter system to paper money. Like money, this standardized DRM system would have to be acknowledged universally, and its rules would have to be easily converted to other systems (the way U.S. dollars are officially used only in America but can be easily converted into other currency). Consumers would no longer have to negotiate separate deals with each provider in order to access the same catalog (more or less). Instead, you — the person, not your device — would have the right to listen to songs, and those rights would follow you around, as long as you’re using an approved device.

The OMC promises to “promote both intellectual property protection and user privacy,” and certainly DReaM, with its focus on interoperability, does seem less draconian than today’s prevailing systems. Even Larry Lessig has endorsed it, pointing with satisfaction to a “fair use” mechanism that is built into the architecture, ensuring that certain uses like quotation, parody, or copying for the classroom are not circumvented. Van Buskirk points out, however, that the fair use protection is optional and left to the discretion of the publisher (not a promising sign). Interestingly, the debate over DReaM has caused a rift among copyright progressives. Van Buskirk points to an August statement from the Electronic Frontier Foundation criticizing DReaM for not going far enough to safeguard fair use, and for falsely donning the mantle of openness:

Using “commons” in the name is unfortunate, because it suggests an online community committed to sharing creative works. DRM systems are about restricting access and use of creative works.

True. As terms like “commons” and “open source” seep into the popular discourse, we should be increasingly on guard against their co-option. Yet I applaud Sun for trying to tackle the interoperability problem, shifting control from the manufacturers to an independent standards body. But shouldn’t mandatory fair use provisions be a baseline standard for any progressive rights scheme? DReaM certainly looks like less of a nightmare than plain old DRM but does it go far enough?

copyright debates continues, now as a comic book

Keith Aoki, James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins have produced a comic book entitled, “Bound By Law? Trapped in a Sturggle She Didn’t Understand” which portrays a fictional documentary filmmaker who learns about intellectual property, copyright and more importantly her rights to use material under fair use. We picked up a copy during the recent conference on “Cultural Environmentalism at 10” at Stanford. This work was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the same people who funded “Will Fair Use Survive?” from the Free Expression Policy Project of the Brennan Center at the NYU Law School, which was discussed here upon its release. The comic book also relies on the analysis that Larry Lessig covered in “Free Culture.” However, these two works go into much more detail and have quite different goals and audiences. With that said, “Bound By Law” deftly takes advantage of the medium and boldly uses repurposed media iconic imagery to convey what is permissible and to explain the current chilling effect that artists face even when they have a strong claim of fair use.

Keith Aoki, James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins have produced a comic book entitled, “Bound By Law? Trapped in a Sturggle She Didn’t Understand” which portrays a fictional documentary filmmaker who learns about intellectual property, copyright and more importantly her rights to use material under fair use. We picked up a copy during the recent conference on “Cultural Environmentalism at 10” at Stanford. This work was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the same people who funded “Will Fair Use Survive?” from the Free Expression Policy Project of the Brennan Center at the NYU Law School, which was discussed here upon its release. The comic book also relies on the analysis that Larry Lessig covered in “Free Culture.” However, these two works go into much more detail and have quite different goals and audiences. With that said, “Bound By Law” deftly takes advantage of the medium and boldly uses repurposed media iconic imagery to convey what is permissible and to explain the current chilling effect that artists face even when they have a strong claim of fair use.

Part of Boyle’s original call ten years ago for a Cultural Environmentalism Movement was to shift the discourse of IP into the general national dialogue, rather than remain in the more narrow domain of legal scholars. To that end, the logic behind capitalizing on a popular culture form is strategically wise. In producing a comic book, the authors intend to increase awareness among the general public as well as inform filmmakers of their rights and the current landscape of copyright. Using the case study of documentary film, they cite many now classic copyright examples (for example the attempt to use footage of a television in the background playing the”Simpsons” in a documentary about opera stagehands.) “Bound By Law” also leverages the form to take advantage of compelling and repurposed imagery (from Mickey Mouse to Mohammed Ali) to convey what is permissible and the current chilling effect that artists face in attempting to deal with copyright issues. It is unclear if and how this work will be received in the general public. However, I can easily see this book being assigned to students of filmmaking. Although, the discussion does not forge new ground, its form will hopefully reach a broader audience. The comic book form may still be somewhat fringe for the mainstream populus and I hope for more experiments in even more accesible forms. Perhaps the next foray into the popular culture will an episode of CSI or Law & Order, or a Michael Crichton thriller.

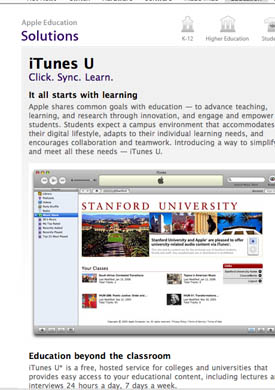

iTunes U: more read/write than you’d think

In Ben’s recent post, he noted that Larry Lessig worries about the trend toward a read-only internet, the harbinger of which is iTunes. Apple’s latest (academic) venture is iTunes U, a project begun at Duke and piloted by seven universities — Stanford, it appears, has been most active.  Since they are looking for a large scale roll out of iTunes U for 2006-07, and since we have many podcasting faculty here at USC, a group of us met with Apple reps yesterday.

Since they are looking for a large scale roll out of iTunes U for 2006-07, and since we have many podcasting faculty here at USC, a group of us met with Apple reps yesterday.

Initially I was very skeptical about Apple’s further insinuation into the academy and yet, what iTunes U offers is a repository for instructors to store podcasts, with several components similar to courseware such as Blackboard. Apple stores the content on its servers but the university retains ownership. The service is fairly customizable–you can store audio, video with audio, slides with audio (aka enhanced podcasts) and text (but only in pdf). Then you populate the class via university course rosters, which are password protected.

There are also open access levels on which the university (or, say, the alumni association) can add podcasts of vodcasts of events. And it is free. At least for now — the rep got a little cagey when asked about how long this would be the case.

The point is to allow students to capture lectures and such on their iPods (or MP3 players) for the purposes of study and review. The rationale is that students are already extremely familiar with the technology so there is less of a learning curve (well, at least privileged students such as those at my institution are familiar).

What seems particularly interesting is that students can then either speed up the talk of the lecture without changing pitch (and lord knows there are some whose speaking I would love to accelerate) or, say, in the case of an ESL student, slow it down for better comprehension. Finally, there is space for students to upload their own work — podcasting has been assigned to some of our students already.

Part of me is concerned at further academic incorporation, but a lot more parts of me are thinking this is not only a chance to help less tech savvy profs employ the technology (the ease of collecting and distributing assets is germane here) while also really pushing the envelope in terms of copyright, educational use, fair use, etc. Apple wants to only use materials that are in the public domain or creative commons initially, but undoubtedly some of the more muddy digital use issues will arise and it would be nice to have academics involved in the process.

rethinking copyright: learning from the pro sports?

As Ben has reported, the Economics of Open Content conference spent a good deal of time discussing issues of copyright and fair use. During a presentation, David Pierce from Copyright Services noted that the major media companies are mainly concerned about protecting their most valuable assets. The obvious example is Disney’s extreme vested interest in protecting the Mickey Mouse, now 78 years old, from entering the public domain. Further, Pierce mentioned that these media companies fight to extend the copyright protection of everything they own in order to protect their most valuable assets. Finally, he stated that only a small portions of their total film libraries are available to consumers. Many people in attendance were intrigued by these ideas, including myself and Paul Courant from the University of Michigan. Earlier in the conference, Courant explained that 90-95% of UM’s library is out of print, and presumably much of that is under copyright protection.

If this situation is true, then, staggering amounts of media are being kept from the public domain or are closed from licensing for little or no reason. A little further thinking quickly leads to alternative structures of copyright that would move media into the public domain or at the least increase its availability, while appeasing the media conglomerates economic concerns.

Rules controlling the protection of assets is nothing new. For instance, in US professional sports, fairly elaborate structures are in place determine how players can be traded. Common sense dictates that teams cannot stockpile players from other teams. In the free agency era of the National Football League, teams have limited rights to control players from signing with other teams. Each NFL team can designate a single athlete as a “franchise” player, according to the current Collecting Bargaining Agreement with the player union. This designation gives them exclusive rights in retaining their player from competing offers. Similarly, in the National Basketball Association, when the league adds a new team, existing teams are allowed to protect eight players from being drafted and signed from the expansion team(s). What can we learn from these institutions? The examples show hoarding players is not good for sports, similarly hoarding assets is not in the best interest of the public good either.

The sports example has obviously limitations. In the NBA, team rosters are limited to fifteen players. On the other hand, a media company can hold an unlimited number of assets. In turn, applying this model would allow companies to seek extensions to only a portion of their copyright assets. Defining this proportion would certainly be difficult. For instance, it is still unclear to me how this might adapt to owners of one copyrighted property.

Another variant interpretation of this model would be to move the burden of responsibility back to the copyright holder. Here, copyright holders must show active economic use and value from these properties. This strategy would force media companies to make their archives available or put the media into the public domain. These copyright holders need to overcome their fears of flooding the markets and dated claims of limited shelf space, which are simply not relevant in the digital media / e-commerce age. Further, media companies would be encouraged to license their holdings for derivatives works, which would in fact lead to more profits. In that, these implementations would increase revenue by challenging the current shortsighted marketing decisions which fail to account for the long tail economic value of their holdings. Although these materials would not enter the public domain, they would be become accessible.

Would this block innovation? Creators of content will still be able to profit from their work for decades. When limited copyright did exist in its original implementation, creative innovation was certainly not hindered. Therefore, the argument that limiting protection of all of a media company’s assets in perpetuity would slow innovation is baseless. By the end of the current time copyright period, holders have ample time to extract value from those assets. In fact, infinite copyright protection slows innovation by removing incentives to create new intellectual property.

Finally, few last comments are worth noting. These models are, at best, compromises. I present them because the current state of copyright protection and extensions seems headed towards former Motion Pictures Association of America President Jack Valenti’s now infamous suggestion of extending copyright to “forever less a day.” Although these media companies have a huge financial stake in controlling these copyrights, I cannot overemphasize our Constitutional right to place these materials in the public domain. Article I, Section 8, clause 8 of the United States Constitution states:

Congress has the power to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Rights to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

Under these proposed schemes, fair use becomes even more cruical. Conceding that the extraordinary preciousness of intellectual property as Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny supersedes rights found in our Constitution implies a similarly extraordinary importance of these properties to our culture and society. Thus, democratic access to these properties for use in education and critical discourse must be equally imperative to the progress of culture and society. In the end, the choice, as a society, is ours. We do not need to concede anything.

fair use and the networked book

I just finished reading the Brennan Center for Justice’s report on fair use. This public policy report was funded in part by the Free Expression Policy Project and describes, in frightening detail, the state of public knowledge regarding fair use today. The problem is that the legal definition of fair use is hard to pin down. Here are the four factors that the courts use to determine fair use:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

From Dysfunctional Family Circus, a parody of the Family Circus cartoons. Find more details at illegal-art.org

Unfortunately, these criteria are open to interpretation at every turn, and have provided little with which to predict any judicial ruling on fair use. In a lawsuit, no one is sure of the outcome of their claim. This causes confusion and fear for individuals and publishers, academics and their institutions. In many cases where there is a clear fair use argument, the target of copyright infringement action (cease and desist, lawsuit) does not challenge the decision, usually for financial reasons. It’s just as clear that copyright owners pursue the protection of copyright incorrectly, with plenty of misapprehension about what qualifies for fair use. The current copyright law, as it has been written and upheld, is fraught with opportunities for mistakes by both parties, which has led to an underutilization of cultural assets for critical, educational, or artistic purposes. Last night I attended a fascinating panel discussion at the American Bar Association on the legality of Google Book Search. In many ways, this was the debate made flesh. Making the case against Google were high-level representatives from the two entities that have brought suit, the Authors’ Guild (Executive Director Paul Aiken) and the Association of American Publishers (VP for legal counsel Allan Adler). It would have been exciting if Google, in turn, had sent representatives to make their case, but instead we had two independent commentators, law professor and blogger Susan Crawford and Cameron Stracher, also a law professor and writer. The discussion was vigorous, at times heated — in many ways a preview of arguments that could eventually be aired (albeit under a much stricter clock) in front of federal judges. …I realize I was over-hasty in dismissing the recent additions made since book scanning resumed earlier this month. True, many of the fine wines in the cellar are there only for the tasting, but the vintage stuff can be drunk freely, and there are already some wonderful 19th century titles, at this point mostly from Harvard. The surest way to find them is to search by date, or by title and date. Specify a date range in advanced search or simply enter, for example, “date: 1890” and a wealth of fully accessible texts comes up, any of which can be linked to from a syllabus. An astonishing resource for teachers and students. Meant to post about this last week but it got lost in the shuffle… In case anyone missed it, Tarleton Gillespie of Cornell has published a good piece in Inside Higher Ed about how sneaky settings in course management software are effectively eating away at fair use rights in the academy. Public debate tends to focus on the music and movie industries and the ever more fiendish anti-piracy restrictions they build into their products (the latest being the horrendous “analog hole”). But a similar thing is going on in education and it is decidely under-discussed. Why aren’t academics – in the humanities in particular – more exercised by recent developments in copyright law? Specifically, why aren’t they outraged by the prospect of indefinite copyright extension?… Most obviously on the doorstep is Google, currently mired in legal unpleasantness for its book-scanning ambitions and the controversial interpretation of fair use that undergirds them. Why aren’t the universities making a clearer statement about this? In defense? In concern? Soon, when search engines move in earnest into video and sound, the shit will really hit the fan. The academy should be preparing for this, staking out ground for the healthy development of multimedia scholarship and literature that necessitates quotation from other “texts” such as film, television and music, and for which these searchable archives will be an essential resource.

This restrictive atmosphere is even more prevalent in the film and music industries. The RIAA lawsuits are a well-known example of the industry protecting its assets via heavy-handed lawsuits. The culture of shared use in the movie industry is even more stifling. This combination of aggressive control by the studio and equally aggressive piracy is causing a legislative backlash that favors copyright holders at the expense of consumer value. The Brennan report points to several examples where the erosion of fair use has limited the ability of scholars and critics to comment on these audio/visual materials, even though they are part of the landscape of our culture.

That’s why

This entry was posted in brennan_center, copyright, Copyright and Copyleft, creative_commons, fair_use, law, open_content and tagged fair_use copyright brennan_center creative_commons open_content law on .

google book search debated at american bar association

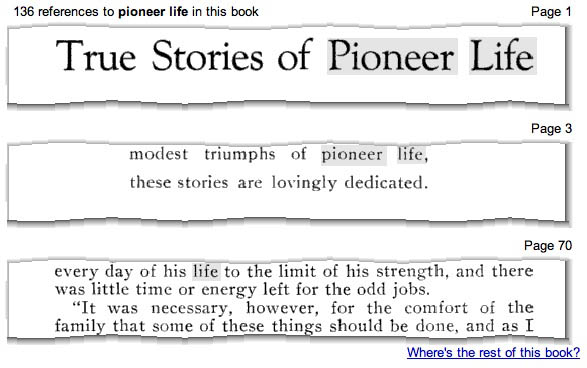

The lawsuits in question center around whether Google’s scanning of books and presenting tiny snippet quotations online for keyword searches is, as they claim, fair use. As I understand it, the use in question is the initial scanning of full texts of copyrighted books held in the collections of partner libraries. The fair use defense hinges on this initial full scan being the necessary first step before the “transformative” use of the texts, namely unbundling the book into snippets generated on the fly in response to user search queries.

…in case you were wondering what snippets look like

At first, the conversation remained focused on this question, and during that time it seemed that Google was winning the debate. The plaintiffs’ arguments seemed weak and a little desperate. Aiken used carefully scripted language about not being against online book search, just wanting it to be licensed, quipping “we’re just throwing a little gravel in the gearbox of progress.” Adler was a little more strident, calling Google “the master of misdirection,” using the promise of technological dazzlement to turn public opinion against the legitimate grievances of publishers (of course, this will be settled by judges, not by public opinion). He did score one good point, though, saying Google has betrayed the weakness of its fair use claim in the way it has continually revised its description of the program.

Almost exactly one year ago, Google unveiled its “library initiative” only to re-brand it several months later as a “publisher program” following a wave of negative press. This, however, did little to ease tensions and eventually Google decided to halt all book scanning (until this past November) while they tried to smooth things over with the publishers. Even so, lawsuits were filed, despite Google’s offer of an “opt-out” option for publishers, allowing them to request that certain titles not be included in the search index. This more or less created an analog to the “implied consent” principle that legitimates search engines caching web pages with “spider” programs that crawl the net looking for new material.

In that case, there is a machine-to-machine communication taking place and web page owners are free to insert programs that instruct spiders not to cache, or can simply place certain content behind a firewall. By offering an “opt-out” option to publishers, Google enables essentially the same sort of communication. Adler’s point (and this was echoed more succinctly by a smart question from the audience) was that if Google’s fair use claim is so air-tight, then why offer this middle ground? Why all these efforts to mollify publishers without actually negotiating a license? (I am definitely concerned that Google’s efforts to quell what probably should have been an anticipated negative reaction from the publishing industry will end up undercutting its legal position.)

Crawford came back with some nice points, most significantly that the publishers were trying to make a pretty egregious “double dip” into the value of their books. Google, by creating a searchable digital index of book texts — “a card catalogue on steroids,” as she put it — and even generating revenue by placing ads alongside search results, is making a transformative use of the published material and should not have to seek permission. Google had a good idea. And it is an eminently fair use.

And it’s not Google’s idea alone, they just had it first and are using it to gain a competitive advantage over their search engine rivals, who in their turn, have tried to get in on the game with the Open Content Alliance (which, incidentally, has decided not to make a stand on fair use as Google has, and are doing all their scanning and indexing in the context of license agreements). Publishers, too, are welcome to build their own databases and to make them crawl-able by search engines. Earlier this week, Harper Collins announced it would be doing exactly that with about 20,000 of its titles. Aiken and Adler say that if anyone can scan books and make a search engine, then all hell will break loose and millions of digital copies will be leaked into the web. Crawford shot back that this lawsuit is not about net security issues, it is about fair use.

But once the security cat was let out of the bag, the room turned noticeably against Google (perhaps due to a preponderance of publishing lawyers in the audience). Aiken and Adler worked hard to stir up anxiety about rampant ebook piracy, even as Crawford repeatedly tried to keep the discussion on course. It was very interesting to hear, right from the horse’s mouth, that the Authors’ Guild and AAP both are convinced that the ebook market, tiny as it currently is, is within a few years of exploding, pending the release of some sort of ipod-like gadget for text. At that point, they say, Google will have gained a huge strategic advantage off the back of appropriated content.

Their argument hinges on the fourth determining factor in the fair use exception, which evaluates “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” So the publishers are suing because Google might be cornering a potential market!!! (Crawford goes further into this in her wrap-up) Of course, if Google wanted to go into the ebook business using the material in their database, there would have to be a licensing agreement, otherwise they really would be pirating. But the suits are not about a future market, they are about creating a search service, which should be ruled fair use. If publishers are so worried about the future ebook market, then they should start planning for business.

To echo Crawford, I sincerely hope these cases reach the court and are not settled beforehand. Larger concerns about Google’s expansionist program aside, I think they have made a very brave stand on the principle of fair use, the essential breathing space carved out within our over-extended copyright laws. Crawford reminded the room that intellectual property is NOT like physical property, over which the owner has nearly unlimited rights. Copyright is a “temporary statutory monopoly” originally granted (“with hesitation,” Crawford adds) in order to incentivize creative expression and the production of ideas. The internet scares the old-guard publishing industry because it poses so many threats to the security of their product. These threats are certainly significant, but they are not the subject of these lawsuits, nor are they Google’s, or any search engine’s, fault. The rise of the net should not become a pretext for limiting or abolishing fair use.

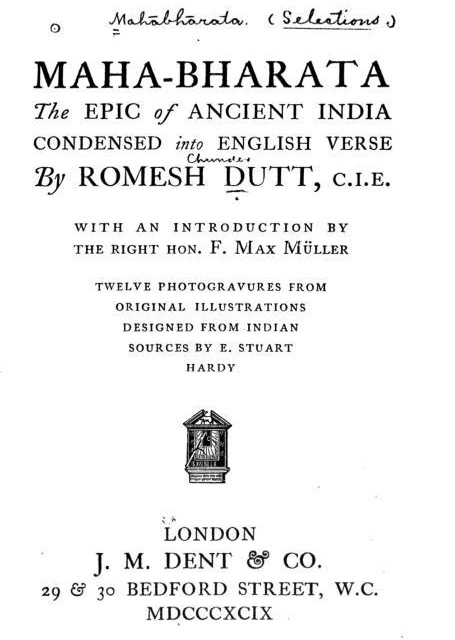

having browsed google print a bit more…

The conclusion: Google Print really is shaping up to be a library, that is, of the world pre-1923 — the current line of demarcation between copyright and the public domain. It’s a stark reminder of how over-extended copyright is. Here’s an 1899 english printing of The Mahabharata:

A charming detail found on the following page is this old Harvard library stamp that got scanned along with the rest:

the creeping (digital) death of fair use

Gillespie draws our attention to the “Copyright Permissions Building Block,” a new add-on for the Blackboard course management platform that automatically obtains copyright clearances for any materials a teacher puts into the system. It’s billed as a time-saver, a friendly chauffeur to guide you through the confounding back alleys of copyright.

But is it necessary? Gillespie, for one, is concerned that this streamlining mechanism encourages permission-seeking that isn’t really required, that teachers should just invoke fair use. To be sure, a good many instructors never bother with permissions anyway, but if they stop to think about it, they probably feel that they are doing something wrong. Blackboard, by sneakily making permissions-seeking the default, plays to this misplaced guilt, lulling teachers away from awareness of their essential rights. It’s a disturbing trend, since a right not sufficiently excercised is likely to wither away.

Fair use is what oxygenates the bloodstream of education, allowing ideas to be ideas, not commodities. Universities, and their primary fair use organs, libraries, shouldn’t be subjected to the same extortionist policies of the mainstream copyright regime, which, like some corrupt local construction authority, requires dozens of permits to set up a simple grocery store. Fair use was written explicitly into law in 1976 to guarantee protection. But the market tends to find a way, and code is its latest, and most insidious, weapon.

Amazingly, few academics are speaking out. John Holbo, writing on The Valve, wonders:

…It seems to me odd, not because overextended copyright is the most pressing issue in 2005 but because it seems like a social/cultural/political/economic issue that recommends itself as well suited to be taken up by academics – starting with the fact that it is right here on their professional doorstep…

Fair use seems to be shrinking at just the moment it should be expanding, yet few are speaking out.