On New Year’s Eve, I got lost in Yonkers trying to take my son’s gently-used toys to the Salvation Army. The Yonkers store was the only one I could find willing to take them. The guy on the phone hesitated, “Are they in good condition?” he asked, clearly unhappy about my impending donation. I assured him they were, and he sighed and told me to come on over.

On principle, I try (really hard) to give away anything that is not completely worn out. But it is getting harder and harder to do. Nobody wants my old furniture or clothes or books. And they especially don’t want used children’s toys. My attempt to give them away was ill-fated. A police barricade stopped me at Nepperhan Avenue (a construction site disaster). Then I drove around for forty minutes until I found an alternate route but was twarted at Ashburton Ave (building on fire, streets blocked). I gave up and went home. With stomach full of guilt, I put the plastic toys in the dumpster. My son didn’t mind because he had a brand new pile of toys in his playroom, Christmas gifts from relatives and friends who couldn’t be dissuaded.

Point is, it seems increasingly difficult to opt out of the cycle of waste-creation. Plastic kids’ toys are just one example. I’m also guilty of consuming and transforming lots of other things into waste: clothes, computers, cell phones, magazines, all sorts of complicatedly-packaged food and beverage items, etc… So yesterday, when I contemplated how best to spend 2008, I decided to focus on figuring out how to create a more sustainable lifestyle. And since I work in book publishing, job one is to figure out what it means to create a sustainable book. Lots of models come to mind. Good ones like Wikipedia (device-neutral and always in the latest, free, edition) and bad ones like the Kindle, (which tries to create a market for an ebook reader with designed obsolescence).

Anyway, I thought it might be useful to weave the sustainability discussion into if:book’s ongoing consideration of networked ebooks, because at this stage in their developement, networked books could be shaped with sustainability in mind. So, I’m hoping to stir up some interesting discussion and serious contemplation of the perfectly sustainable book: one that is constantly revised, but never needs to be reprinted (or repurchased); one that is lean and simple and doesn’t require a small server farm or a special device; one that makes an enormous impact, but leaves a teeny tiny carbon footprint; one we can live with for ever and ever without getting bored or satiated.

Category Archives: environment

digital wasteland

In a technology-driven culture where planned obsolescence and perpetual upgrades are the rule, electronic waste – the computer hardware and consumer electronics we continuously discard – is becoming a problem of epidemic proportions. 20 to 50 million tons of it are generated annually, most of which gets shipped off to places like India, China and Kenya, where complex scavenger economies have sprung up around vast electronics dumping grounds filled with leaking toxins and treacherous chemicals. Foreign Policy just published a powerful photo essay documenting this very real footprint left by our so-called virtual lives.

Of course it’s not just what we throw away that’s problematic, but what we consume. Many today are awakening to the fact that most of the industrial conveniences we enjoy – abundant food shipped from anywhere, cheap transportation, and various other luxuries – carry a dire hidden cost to the planet’s fragile climate and ecology. Like it or not, instant and ubiquitous communication through digital networks also requires fuel. It was recently estimated that the average Second Life avatar consumes as much energy annually (all those servers huffing and puffing) as the average Brazilian.

There are other stories that reveal the uncleanness of our technology. Read this section (paragraphs 45 and 46) of Gamer Theory about the tragic case of coltan mining in Congo. Coltan is a rare mineral used to make conductors in the Sony Playstation, and its scarcity and high demand have made it the source of violent conflict in that country.

These are problems that are difficult to wrap one’s mind around, so totally do they challenge our fundamental patterns of existence. One can begin, I suppose, by acting locally. On a crisp, sunny day in New York this past January, walking across a large stretch of asphalt on the north end of Union Square usually populated by organic farmers’ stalls or packs of skateboarders idly rehearsing their moves, I found myself standing before a sea of old computers, cellphones and other discarded electronics spread out across the ground. As I stared agape, energetic volunteers, bundled up against the cold, darted around the piles, sorting, wrapping and carting the junk into a large truck. It was a computer recycling drive organized by the Lower East Side Ecology Center in partnership with the NYCWasteLe$$ program. A heartening sight that I couldn’t resist recording with my cameraphone.

Here’s a little photo essay from our neck of the woods:

benevolent conspiracy

“Fuel prices jumped this week, led by gasoline which gained over a dollar a gallon on average. Oil distributors pointed to several “renegotiated” delivery contracts as proof that a long-rumored shortfall in the supply of U.S. oil has finally arrived. Oil producers were tight-lipped about the adjusted contracts, and as I write this it’s still unclear how extensive the shortfall will turn out to be.”

And thus the stage is set for World Without Oil, the social consciousness-raising ARG (alternate reality game) launched today by Jane McGonigal and associates. I’m already in flagrant violation of the “this is not a game” convention that governs all ARGs, but since this something I and others here at the Institute aim to follow closely in the coming weeks and months, we’ll have to treat the curtain between fact and fiction as semi-transparent.

From the perspective of our research here, I’m deeply intrigued because the ARG is an entirely net-native storytelling genre, employing forms as diverse and scattered as the media landscape we live in today. ARGs don’t rely on a specific software application, game system or OS, rather they treat the entire Internet as their platform. Players typically employ a whole battery of information technologies — email, chat, blogs, search engines, message boards, wikis, social media sites, cell phones — in pursuit of an elusive narrative thread.

The story is usually spun through cryptic clues and half-disclosures, one bread crumb at a time, by the game’s authors, or “puppetmasters.” To have any hope of success, players must work together, sharing clues and pooling information as they go. The whole point is to make the story into a group obsession — to mobilize players into problem-solving collectives where they can debate and test different hypotheses as a smart mob. It’s sort of like surfing an alternate version of the net, using all the social search tactics of the real one.

Of course, the net is a murky territory, full of conspiracy theories, identity traps and misinformation. ARGs take this uncertainty and make it their idiom. The game (remember, it’s not a game) might involve websites that to the casual observer look perfectly real — a corporate home page, a personal blog — but that are in fact a part of the fiction. ARGs use the playbook of spammers, phishers and social reality hackers like the Yes Men to create a fictional universe that blends seamlessly with the real.

But we’re not just talking about an alternate net here, we’re talking about an alternative world. ARGs frequently assign tasks that pull players away from their computers and propel them into their physical environment (the phenomenally popular I Love Bees had people running all over San Francisco answering pay phones). This couldn’t be more unlike the whole Second Life phenomenon (which, as you may have noticed, we’ve barely covered here). Instead of building a one-to-one simulacrum of the actual world (yeah yeah, you can fly, big whoop), this takes the actual world and tilts it — reinterprets it. There’s imagination happening here.

World Without Oil takes this in a new direction. McGonigal has been talking for some time now about using ARGs for more than just pure play. She believes they could be harnessed to solve real world problems (for more about this, read this recent long piece in SF Weekly by Eliza Strickland). Hence the premise of oil shocks. The WWO website was set up by ten friends who met in the chaos of the Denver Airport during the blizzards this past December. During that time, they bonded and got to talking about citizen journalism and the potential of the web for organizing masses of people to deal with crises without having to rely solely on big media and big government. A weird tip about an impending oil crisis on April 30th got their paranoid wheels turning and they decided to set up a central hub for netizens to send reportage and personal testimonies about life during the shocks. Today is April 30 and lo and behold: the shocks have arrived!

The idea is to collectively imagine a reality that could very likely come to pass, and to share information and ideas — alternative energy innovations, new forms of transport, new forms of community — that could help us get through it. It’s an opportunity for self-reeducation and perhaps the forging of some real-world relationships. There’s even a page for teachers to guide students through this collaborative hallucination, and to learn something about energy geopolitics as they do it.

As an entry to the serious games movement, this has to be one of the most innovative efforts out there. But I find myself wondering whether simply getting everyone to report from their corner of the crisis — postcards from the apocalypse –will be enough to create a full-blown ARG phenomenon. Is this participatory in quite the right way? While I ecstatically applaud the intention here of repurposing a form that to date has been employed mainly as a viral marketing tool (the first ARG was built around Spielberg’s “A.I.” in 2001), I worry that the WWO construct seems to have been shorn of most of the usual mystery elements — the codes, clues and crumbs — that make ARGs so addictive. There’s a whiff of homework here, something perhaps a little too earnest, that could prevent it from gaining traction. I sincerely hope I’m wrong.

Still, even if this fails to take off, I think this is an important milestone and will be important to study as it unfolds. WWO suggests what could be the ideal dystopian form for the cultural moment: a mode of storytelling that taps directly into the present human condition of networked information blitz and tries to channel it toward real-world awareness, or even action. The ARG adopts tactics long employed in military war games and conflict exercises and turns them (at least potentially) toward grassroots activism. WWO is trying to rouse, as Sebastian Mary put it in a previous post, our “democratic imagination. In SF Weekly piece I link to above, McGonigal puts it this way:

“When you start projecting that out to bigger scales, that’s when these games start to look like a real way to achieve, if not world peace, then some kind of world-benevolent conspiracy, where we feel like we are all playing the same game.”

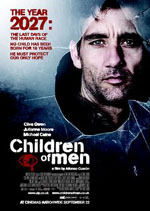

Many people I know loved the film “Children of Men” by Alfonso Cuarón because they felt that it showed them, with the cutting clarity of allegory, the way the world really is. The premise, that the human race has lost the ability to reproduce itself (a dying world, without children, slowly self-destructing), was of course implausible, but all the same it felt like a layer was being peeled away to reveal a terrible truth. Probably the most unsettling moment for me was the lights rose at the end and we exited the theater into the street. Everything looked different, fragile, like something awful was being hidden just beneath the surface. But the feeling soon faded and I filed the experience away: “Children of Men”; a brilliant film; one of the year’s best; shamefully overlooked at the Oscars.

Many people I know loved the film “Children of Men” by Alfonso Cuarón because they felt that it showed them, with the cutting clarity of allegory, the way the world really is. The premise, that the human race has lost the ability to reproduce itself (a dying world, without children, slowly self-destructing), was of course implausible, but all the same it felt like a layer was being peeled away to reveal a terrible truth. Probably the most unsettling moment for me was the lights rose at the end and we exited the theater into the street. Everything looked different, fragile, like something awful was being hidden just beneath the surface. But the feeling soon faded and I filed the experience away: “Children of Men”; a brilliant film; one of the year’s best; shamefully overlooked at the Oscars.

What would “Children of Men” look like as an ARG? What would a networked tactic bring to this story? Would it be simply dispatches from a dying world, or could we do something more constructive? Could the darkened theater and the streets outside somehow be merged?

Our first stories were oral stories. When we were children our parents read to us aloud stories that we listened to over and over again until they were embedded in our unconscious. We knew the stories inside and out, backwards and forwards. Reading became a ritual of call and response: a physical act. In the classroom too, teachers read aloud to us. We knew the stories inside and out, backwards and forwards. Call and response. At recess we ran out into the playground and re-eanacted the stories — replayed them, spun new ones. Those early experiences hearken back to earlier cultures — oral, pre-literate ones where the word was less the realm of contemplation and more the realm of action. ARGs seem to tap into this power of the oral story — the spark of the imagination and then the dash, together, into the playground.

world without oil: democratic imagination?

I’ve written a couple of times recently about alternate reality gaming as an emergent genre of Web-native storytelling. But one of the things that’s puzzled and frustrated me is the fact that the stories played out in most of these games tend to revolve around sinister cults, reborn gods, out-of-control AIs, government conspiracies and suchlike: the bread-and-butter paranoias that permeate the Web. No criticism here, I should add. Asking ‘What if all this were true?’ can kick-start a very entertaining daydream.

But in exploring these games, and reading around them, it becomes clear that the way these stories are told is as interesting as their content. In particular, there is a tendency (see this paper by academic and game designer Jane McGonigal for example) for ARG-style collaborative problem-solving to escape the boundaries of gaming and become a real-world way for distributed groups of people to address a problem they cannot fix by themselves.

In addition, the founding dramatic convention is “This Is Not A Game.” That is, the games are supposed to leak out into players’ lives. And this, combined with a chance to practice widespread collaborative problem-solving, is a phenomenally powerful and intriguingly democratic artistic form. So why, I wanted to know, is no-one using it to address contemporary politics?

No sooner do I formulate the thought than I discover that McGonigal’s latest project, trailed in a talk she gave at the 2007 San Francisco game developers’ conference , is an ARG called World Without Oil. Its central characters believe that an oil crisis is approaching on April 30 – the game’s launch date – and are trying to spread the word. Or are they…? Who is trying to stop them…? And we’re off.

I’ll be following this one closely. Rather than taking a fantastical theme, it invites players to think seriously about a situation which is increasingly imaginable in the near future. And it seems that people are ready to engage: since its appearance yesterday, the the Unfiction discussion thread about the game is already many pages long, and mixes discussion of the game with serious musings about the very real possibility of a world without oil.

It also looks as though it’s going to go way beyond asking its players to solve ROT-13 encryption for the next clue. In this Gamasutra interview McGonigal explains her ideas about collective intelligence and gaming, and outlines the way in which World Without Oil will be not just a game but a collaborative storytelling process. Along with the narrative of the main fictional characters, players will be invited to create blogs detailing – as if it were happening – the problems they would face in a (so far) fictional world without oil. And the game will respond. So, in effect, it will invite players to take part in a huge collaborative exercise in imagining a very possible future.

Looking at this game, I was reminded of the RSA’s response to the Stern report on climate change, where it was pointed out that reactions to climate change and the like often lurch between optimism and pessimism without progressing beyond high emotion to imaginative or practical engagement with the situation. On a similar tack, Dougald Hine wrote an article recently for opendemocracy discussing climate change as a challenge to the democratic imagination: “Whether or not we succeed technically in mitigating its effects, it is all too easy to envisage the result as a more or less unpleasant authoritarian future. The task is to imagine and bring about a future which can accommodate both austerity and autonomy.”

It may be too soon to tell. But if it goes well, I have some hope that World Without Oil may manage to engage not just collective fear but a collective and collaborative imagination to address some increasingly urgent questions.

knightfall

Knight Ridder, America’s second largest newspaper company, operator of 32 dailies, has been purchased by McClatchy Co., a smaller newspaper company (reported here in the San Jose Mercury News, one of the papers McClatchy has acquired). Several months ago, Knight Ridder’s controlling shareholders, nervous about declining circulation and the increasing dominance of internet news, insisted that the company put itself up for auction. After being sniffed over and ultimately dropped by Gannett Co., the country’s largest print news conglomerate, the smaller McClatchy came through with KR’s sole bid.

Knight Ridder, America’s second largest newspaper company, operator of 32 dailies, has been purchased by McClatchy Co., a smaller newspaper company (reported here in the San Jose Mercury News, one of the papers McClatchy has acquired). Several months ago, Knight Ridder’s controlling shareholders, nervous about declining circulation and the increasing dominance of internet news, insisted that the company put itself up for auction. After being sniffed over and ultimately dropped by Gannett Co., the country’s largest print news conglomerate, the smaller McClatchy came through with KR’s sole bid.

McClatchy’s chief exec calls it: “a vote of confidence in the newspaper industry.” Or is it — to riff on the cultural environmentalism metaphor — like buying beach front property on the Aral Sea?

For a more hopeful view on the future of news, Jay Rosen (who has not yet commented on the Knight Ridder sale) has an amazing post today on Press Think about online newspapers as “seeders of clouds” and “public squares.” Very much worth a read.

cultural environmentalism symposium at stanford

Ten years ago, the web just a screaming infant in its cradle, Duke law scholar James Boyle proposed “cultural environmentalism” as an overarching metaphor, modeled on the successes of the green movement, that might raise awareness of the need for a balanced and just intellectual property regime for the information age. A decade on, I think it’s safe to say that a movement did emerge (at least on the digital front), drawing on prior efforts like the General Public License for software and giving birth to a range of public interest groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Creative Commons. More recently, new threats to cultural freedom and innovation have been identified in the lobbying by internet service providers for greater control of network infrastructure. Where do we go from here? Last month, writing in the Financial Times, Boyle looked back at the genesis of his idea:

We were writing the ground rules of the information age, rules that had dramatic effects on speech, innovation, science and culture, and no one – except the affected industries – was paying attention.

My analogy was to the environmental movement which had quite brilliantly made visible the effects of social decisions on ecology, bringing democratic and scholarly scrutiny to a set of issues that until then had been handled by a few insiders with little oversight or evidence. We needed an environmentalism of the mind, a politics of the information age.

Might the idea of conservation — of water, air, forests and wild spaces — be applied to culture? To the public domain? To the millions of “orphan” works that are in copyright but out of print, or with no contactable creator? Might the internet itself be considered a kind of reserve (one that must be kept neutral) — a place where cultural wildlife are free to live, toil, fight and ride upon the backs of one another? What are the dangers and fallacies contained in this metaphor?

Ray and I have just set up shop at a fascinating two-day symposium — Cultural Environmentalism at 10 — hosted at Stanford Law School by Boyle and Lawrence Lessig where leading intellectual property thinkers have converged to celebrate Boyle’s contributions and to collectively assess the opportunities and potential pitfalls of his metaphor. Impressions and notes soon to follow.

hacking nature

Slate is trying something new with its art criticism: a new “gallery” feature where each month an important artist will be discussed alongside a rich media presentation of their work.

…we’re hoping to emphasize exciting new video and digital art–the kind of art that is hard to reproduce in print magazines.

For their first subject, they don’t push the print envelope terribly far (just a simple slideshow), but they do draw attention to some stunning work by Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, who (happily for us New Yorkers) has shows coming this week to the Brooklyn Museum and the Charles Cowles Gallery in Manhattan. Burtynsky documents landscapes bearing the mark of extreme human exploitation – the infernal streams flowing from nickel mines, junked ocean liners rusting in chunks on the beach, abandoned quarries ripe with algae in their cubic trenches, and an arresting series from recent travels through China’s industrial belt.

These photographs carry startling information through the image-surplussed web. But Burtynsky disappoints in one vital, perhaps deciding, respect:

…his position on the moral and political implications of his work is studiously neutral. He doesn’t point fingers or call for change; instead, he accepts industry’s exploitation of the land as the inevitable result of modern progress. “We have extracted from the land from the moment we stood on two feet,” he said in an interview in the exhibition catalog. “The entire 20th century has been a revving up of this large consumptive engine. It’s not a question of whether we are going to stop consuming. It’s not going to happen…”

As someone who believes that struggling to prevent (or at least mitigate) global ecological disaster should be the transcending narrative of our times, I find Burtynsky’s detachment deeply depressing and self-defeating. His images glory in the sick beauty of these ravaged scenes, and the cultural consumers that will no doubt pay large sums for these photographs at his upcoming Chelsea show only compound the cynicism.