Here is a follow up on the our post about Goodmail. A few weeks ago Esther Dyson wrote an op-ed piece in the New York Times in support of the Goodmail service, a start up which charges fees to senders of email to ensure their delivery. She argues that the services by either Goodmail or others are inevitable and will provide value of email recipients by eliminating spam. While I agree that customers should be allowed to chose whatever services they want, many of Dyson’s claims need to further examined to see if they make sense.

Dyson claims:

“I agree that pretty soon sending most e-mail will cost money, but I think that’s only right. It costs money to guarantee quality and safety. Moreover, I think the market will work, and that it will not shut out deserving senders, if we only let it work freely…”

“…In the short run, AOL and others will serve as the recipients’ proxies. If they don’t do a good job of ensuring that customers get the mail they want, even from nonpaying senders, they will lose their customers…

I’m not clear on how market competition requires additional cost to users. People are already free to chose email providers based on their spam filters. Email earns revenue for providers. Even yahoo, gmail and hotmail earn money through ads and sponored links. Adding another layer of fees will only give email providers an economic incentive to abandon their spam filters, which will make senders of email feel obligated to pay for these extra services. Email providers currently have incentives to continually improve their spam filters, which work rather well. Employing more strategies along the lines of improved mechanisms for users to report spam seem to be a more fairly distribution of the costs of insuring the delivery of email.

“And in the long run, recipients will be able to use services like Goodmail to set their own prices for receiving mail.

In my case, I’d have a list. I’d charge nothing for people I know, 50 cents for anyone new (though if I add the sender to my list after reading the mail, I’ll cancel the 50 cents) and $3 for random advertisers. Ex-boyfriends pay $10.”

I doubt the practicality of this scheme. It would only work if people receive email, open it, and approve new addresses, in a timely matter. People do not read all their email, as I’ve seen Inboxes with thousands of emails, many of them unopened. People forget that they have requested information, which would lead to disputed charged. People abandon email addresses and they accidentally erase email from servers. People change their minds on what spam is. Sometimes, email updates which people sign up to receive and later the become spam. If a firm buys an email list in good faith, are they open to these fines as well? The thought of resolving all these disputes of who wanted what email would be a bureaucratic mess.

“If people like those little stamps that mark their mail as safe and wanted or as commercial transactions, then let the customers have them. And let other companies compete with Goodmail to offer better and less expensive service.”

Goodmail is not passing on costs to receivers, but to senders. The companies who will feel the most effect are the ones with less resources, for example as she notes, non-profit organizations. Why this has to be true is still unclear to me.

Category Archives: email

the email tax: an internet myth soon to become true

After years as an Internet urban myth, the email tax appears to be close at hand. The New York TImes reports that AOL and Yahoo have partnered with startup Goodmail to start offering guaranteed delivery of mass email to organizations for a fee. Organizations with large email lists can pay to have their email go directly to AOL and Yahoo customers’ inboxes, bypassing spam filters. Goodmail claims that they will offer discounts to non-profits.

Moveon.org and the Electronic Frontier Foundation have joined together to create an alliance of nonprofit and public interest organizations to protest AOL’s plans. They argue that this two-tiered system will create an economic incentive to decrease investment into AOL’s spam filtering in order to encourage mass emailers to use the pay-to-deliver service. They have created an online petition called dearaol.com for people to request that AOL stop these plans. A similar protest to Yahoo who intends to launch this service after AOL is being planned as well. The alliance has created unusual bedfellows, including Gun Owners of America, AFL-CIO, Humane Society of United States and Human Rights Campaign, who are resisting the pressure to use this service.

Part of the leveling power of email is that the marginal cost of another email is effectively zero. By perverting this feature of email, smaller businesses, non-profits, and individuals will once again be put at a disadvantage to large affluent firms. Further, this service will do nothing to reduce spam, rather it is designed to help mass emailers. An AOL spokesman, Nicholas Graham is quoted as saying AOL will earn revenue akin to a “lemonade stand” which further questions by AOL would pursue this plan in the first place. Although the only affected parties will initially be AOL and Yahoo users, it sets a very dangerous precedent that goes against the democratizing spirit of the Internet and digital information.

washington post and new york times hyperlink bylines

In an effort to more directly engage readers, two of America’s most august daily newspapers are adding a subtle but potentially significant feature to their websites: author bylines directly linked to email forms. The Post’s links are already active, but as of this writing the Times, which is supposedly kicking off the experiment today, only links to other articles by the same reporter. They may end up implementing this in a different way.

screen grab from today’s Post

The email trial comes on the heels of two notoriously failed experiments by elite papers to pull readers into conversation: the LA Times’ precipitous closure, after an initial 24-hour flood of obscenities and vandalism, of its “wikatorials” page, which invited readers to rewrite editorials alongside the official versions; and more recently, the Washington Post’s shutting down of comments on its “post.blog” after experiencing a barrage of reader hate mail. The common thread? An aversion to floods, barrages, or any high-volume influx of unpredictable reader response. The email features, which presumably are moderated, seem to be the realistic compromise, favoring the trickle over the deluge.

In a way, though, hyperlinking bylines is a more profound development than the higher profile experiments that came before, which were more transparently about jumping aboard the wiki/blog bandwagon without bothering to think through the implications, or taking the time — as successful blogs and wikis must always do — to gradually build up an invested community of readers who will share the burden of moderating the discussion and keeping things reasonably clean. They wanted instant blog, instant wiki. But online social spaces are bottom-up enterprises: invite people into your home without any preexisting social bonds and shared values — and add to that the easy target of being a mass media goliath — and your home will inevitably get trashed as soon as word gets out.

Being able to email reporters, however, gets more at the root of the widely perceived credibility problem of newspapers, which have long strived to keep the human element safely insulated behind an objective tone of voice. It’s certainly not the first time reporters’ or columnists’ email addresses have been made available, but usually they get tucked away toward the bottom. Having the name highlighted directly beneath the headline — making the reporter an interactive feature of the article — is more genuinely innovative than any tacked-on blog because it places an expectation on the writers as well as the readers. Some reporters will likely treat it as an annoying new constraint, relying on polite auto-reply messages to maintain a buffer between themselves and the public. Others may choose to engage, and that could be interesting.

the selected, annotated outbox of dave eggers

Email killed the practice of letter-writing so suddenly that we haven’t a chance to think about the consequences. The Times Book Review ran an essay this weekend on the problem this poses for literary historians, biographers and archivists, who long have relied on collected letters and papers to fill in the gaps between a writer’s published work. In the same review, the Times covers a new biography of the legendary critic Edmund Wilson largely based on his correspondences, and last week covered a new collection of the letters of poet James Wright. Letters are often treated as literature in themselves.

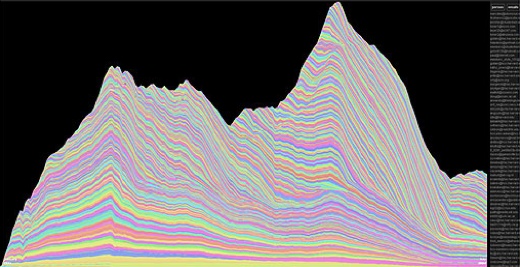

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

There isn’t necessarily anything less rich about email correspondence. It excels at capturing a vibrant volley of words with great immediacy, whereas paper letters permit deeper communiques, fewer and father between. But in some cases, these characterizations do not hold up. With reliable postal service, letters can fly back and forth quite rapidly. And just because an email suddenly appears in your box does not mean that it will be immediately read, let alone replied to. Sometimes we write long email letters, expecting that the receiver is busy and will take time to reply. These differences, true and false, are worth evaluating.

But if collected emails are to become a literary tool, there is no question that we will need more reliable ways of archiving and preserving digital correspondence. We will also need new editorial approaches for collecting and publishing them. A printed volume, or series of volumes, might be insufficient for presenting a massive 4 gigabyte email archive by Dave Eggers (No one wants to read the phone book from cover to cover). And according to the Times piece, Eggers’ agent Andrew Wylie is mulling over such a project. What would make more sense is an electronic edition that is essentially a selected or complete annotated Eggers Outbox, with folders and tags provided for categorization, a powerful search function, and the ability to organize according to your own interests. There would also be browsing and skimming tools that would allow a reader to move rapidly across vast tracts of correspondence and still find what they are looking for. And maybe, a way to email the author yourself and become a part of the living archive.