an open letter to claire israel

Less than two months after reaching a deal with Microsoft, the University of California has agreed to let Google scan its vast holdings (over 34 million volumes) into the Book Search database. Google will undoubtedly dig deeper into the holdings of the ten-campus system’s 100-plus libraries than Microsoft, which is a member of the more copyright-cautious Open Content Alliance, and will focus primarily on books unambiguously in the public domain. The Google-UC alliance comes as major lawsuits against Google from the Authors Guild and Association of American Publishers are still in the evidence-gathering phase.

Meanwhile, across the drink, French publishing group La Martiniè re in June brought suit against Google for “counterfeiting and breach of intellectual property rights.” Pretty much the same claim as the American industry plaintiffs. Later that month, however, German publishing conglomerate WBG dropped a petition for a preliminary injunction against Google after a Hamburg court told them that they probably wouldn’t win. So what might the future hold? The European crystal ball is murky at best.

During this period of uncertainty, the OCA seems content to let Google be the legal lightning rod. If Google prevails, however, Microsoft and Yahoo will have a lot of catching up to do in stocking their book databases. But the two efforts may not be in such close competition as it would initially seem.

Google’s library initiative is an extremely bold commercial gambit. If it wins its cases, it stands to make a great deal of money, even after the tens of millions it is spending on the scanning and indexing the billions of pages, off a tiny commodity: the text snippet. But far from being the seed of a new literary remix culture, as Kevin Kelly would have us believe (and John Updike would have us lament), the snippet is simply an advertising hook for a vast ad network. Google’s not the Library of Babel, it’s the most sublimely sophisticated advertising company the world has ever seen (see this funny reflection on “snippet-dangling”). The OCA, on the other hand, is aimed at creating a legitimate online library, where books are not a means for profit, but an end in themselves.

Brewster Kahle, the founder and leader of the OCA, has a rather immodest aim: “to build the great library.” “That was the goal I set for myself 25 years ago,” he told The San Francisco Chronicle in a profile last year. “It is now technically possible to live up to the dream of the Library of Alexandria.”

So while Google’s venture may be more daring, more outrageous, more exhaustive, more — you name it –, the OCA may, in its slow, cautious, more idealistic way, be building the foundations of something far more important and useful. Plus, Kahle’s got the Bookmobile. How can you not love the Bookmobile?

Engadget has it from inside sources at Apple that a next-generation iPod is in the works with a larger screen and a full-fledged text reader:

Engadget has it from inside sources at Apple that a next-generation iPod is in the works with a larger screen and a full-fledged text reader:

…two bits from separate, trustworthy insiders that Apple’s not satisfied merely vending Audible‘s books-on-digital-audio solution. With the iRex iLiad and Sony PRS-500 Portable Reader both right around the corner, is it possible the next iPod might catch the eBook bug? We’d say the possibility is very real, since according to a source at a major publishing house, they were just ordered to archive all their manuscripts — every single one — and send them over to Apple’s Cupertino HQ.

So Audible, huh? Interesting. They got a toehold in the market with audiobooks, and may now be making the transition to ebooks.

A separate trusted source let us know that the next iPod will have a substantial amount of screen real estate (as we’d all suspected), as well as a book reading mode that pumps up the contrast and drops into monochrome for easy reading. It’s no e-ink, sure, but a widescreen iPod would be well suited for the purpose, and according to our source, the books you’d buy (presumably through iTunes) won’t have an expiration…

I’d hope that such a device would have wifi, a web browser and an RSS reader that could be taken offline. I think that books will only be a part of the equation.

Teleread has the ebook standards angle.

Much of our time here is devoted to the extreme electronic edge of change in the arena of publishing, authorship and reading. For some, it’s a more distant future than they are interested in, or comfortable, discussing. But the economics and means/modes of production of print are being no less profoundly affected — today — by digital technologies and networks.

The Times has an article today surveying the landscape of print-on-demand publishing, which is currently experiencing a boom unleashed by advances in digital technologies and online commerce. To me, Lulu is by far the most interesting case: a site that blends Amazon’s socially networked retail formula with a do-it-yourself media production service (it also sponsors an annual “Blooker” prize for blog-derived books). Send Lulu your book as a PDF and they’ll produce a bound print version, in black-and-white or color. The quality isn’t superb, but it’s cheap, and light years ahead of where print-on-demand was just a few years back. The Times piece mentions Lulu, but focuses primarily on a company called Blurb, which lets you design books with customized software called BookSmart, which you can download free from their website. BookSmart is an easy-to-learn, template-based assembly tool that allows authors to assemble graphics and text without the skills it takes to master professional-grade programs like InDesign or Quark. Blurb books appear to be of higher quality than Lulu’s, and correspondingly, more expensive.

Reading this reminded me of an email I received about a month back in response to my “Physical Books and Networks” post, which looked at authors who straddle the print and digital worlds. It came from Abe Burmeister, a New York-based designer, writer and artist, who maintains an interesting blog at Abstract Dynamics, and has also written a book called Economies of Design and Other Adventures in Nomad Economics. Actually, Burmeister is still in the midst of writing the book — but that hasn’t stopped him from publishing it. He’s interested in process-oriented approaches to writing, and in situating acts of authorship within the feedback loops of a networked readership. At the same time, he’s not ready to let go of the “objectness” of paper books, which he still feels is vital. So he’s adopted a dynamic publishing strategy that gives him both, producing what he calls a “public draft,” and using Lulu to continually post new printable versions of his book as they are completed.

Reading this reminded me of an email I received about a month back in response to my “Physical Books and Networks” post, which looked at authors who straddle the print and digital worlds. It came from Abe Burmeister, a New York-based designer, writer and artist, who maintains an interesting blog at Abstract Dynamics, and has also written a book called Economies of Design and Other Adventures in Nomad Economics. Actually, Burmeister is still in the midst of writing the book — but that hasn’t stopped him from publishing it. He’s interested in process-oriented approaches to writing, and in situating acts of authorship within the feedback loops of a networked readership. At the same time, he’s not ready to let go of the “objectness” of paper books, which he still feels is vital. So he’s adopted a dynamic publishing strategy that gives him both, producing what he calls a “public draft,” and using Lulu to continually post new printable versions of his book as they are completed.

His letter was quite interesting so I’m reproducing most of it:

Using print on demand technology like lulu.com allows for producing printed books that are continuously being updated and transformed. I’ve been using this fact to develop a writing process loosely based upon the linux “release early and release often” model. Books that essentially give the readers a chance to become editors and authors a chance to escape the frozen product nature of traditional publishing. It’s not quite as radical an innovation as some of your digital and networked book efforts, but as someone who believes there always be a particular place for paper I believe it points towards a subtly important shift in how the books of the future will be generated.

…one of the things that excites me about print on demand technology is the possibilities it opens up for continuously evolving books. Since most print on demand systems are pdf powered, and pdfs have a degree of programability it’s at least theoretically possible to create a generative book; a book coded in such a way that each time it is printed an new result comes out. On a more direct level though it’s also very practically possible for an author to just update their pdf’s every day, allowing for say a photo book to contain images that cycle daily, or the author’s photo to be a web cam shot of them that morning.

When I started thinking about the public drafting process one of the issues was how to deal with the fact that someone might by the book and then miss out on the content included in the edition that came out the next day. Before I received my first hard copies I contemplated various ways of issuing updated chapters and ways to decide what might be free and what should cost money. But as soon as I got that hard copy the solution became quite clear, and I was instantly converted into the Cory Doctrow/Yochai Benkler model of selling the book and giving away the pdf. A book quite simply has a power as an object or artifact that goes completely beyond it’s content. Giving away the content for free might reduce books sales a bit (I for instance have never bought any of Doctrow’s books, but did read them digitally), but the value and demand for the physical object will still remain (and I did buy a copy of Benkler’s tome.) By giving away the pdf, it’s always possible to be on top of the content, yet still appreciate the physical editions, and that’s the model I have adopted.

And an interesting model it is too: a networked book in print. Since he wrote this, however, Burmeister has closed the draft cycle and is embarking on a total rewrite, which presumably will become a public draft at some later date.

Much as I hate to dredge up Updike and his crusty rejoinder to Kevin Kelly’s “Scan this Book” at last month’s Book Expo, The New York Times has refused to let it die, re-printing his speech in the Sunday Book Review under the headline, “The End of Authorship.” We should all thank the Times for perpetuating this most uninteresting war of words about the publishing future. Here, once again, is Updike:

Books traditionally have edges: some are rough-cut, some are smooth-cut, and a few, at least at my extravagant publishing house, are even top-stained. In the electronic anthill, where are the edges? The book revolution, which, from the Renaissance on, taught men and women to cherish and cultivate their individuality, threatens to end in a sparkling cloud of snippets.

I was reading Christine Boese’s response to this (always an exhilarating antidote to the usual muck), where she wonders about Updike’s use of history:

The part of this that is the most peculiar to me is the invoking of the Renaissance. I’d characterize that period as a time of explosive artistic and intellectual growth unleashed largely by social unrest due to structural and technological changes.

….swung the tipping point against the entrenched power arteries of the Church and Aristocracy, toward the rising merchant class and new ways of thinking, learning, and making, the end result was that the “fruit basket upset” of turning the known world’s power structures upside down opened the way to new kinds of art and literature and science.

So I believe we are (or were) in a similar entrenched period like that now. Except that there is a similar revolution underway. It unsettles many people. Many are brittle and want to fight it. I’m no determinist. I don’t see it as an inevitability. It looks to me more like a shift in the prevailing winds. The wind does not deterministically affect all who are buffeted the same way. Some resist, some bend, some spread their wings and fly off to wherever the wind will take them, for good or ill.

Normally, I’d hope the leading edge of our best artists and writers would understand such a shift, would be excited to be present at the birth of a new Renaissance. So it puzzles me that John Updike is sounding so much like those entrenched powers of the First and Second Estate who faced the Enlightenment and wondered why anyone would want a mass-printed book when clearly monk-copied manuscripts from the scriptoria are so much better?!

I say it again, it’s a shame that Kelly, the uncritical commercialist, and Updike, the nostaligic elitist, have been the ones framing the public debate. For most of us, Google is neither the eclipse nor dawn of authorship, but just a single feature of a shifting landscape. Search is merely a tool, a means: the books themselves are the end. Yet, neither Google Book Search, which is simply an apparatus for extracting new profits off of the transmission and search of books, nor the present-day publishing industry, dominated as it is by mega-conglomerates with their penchant for blockbusters (our culture haunted by vast legions of the out-of-print), serves those ends very well. And yet these are the competing futures of the book: lonely forts and sparkling clouds. Or so we’re told.

What is a book? This is a question we will want to answer if we want to enable books to reflect the electronic age and not the ink-on-paper era, just as Gutenberg and his heirs fully exploited that once-new technology back when, well, the ink was still fresh.

I don’t think a precise definition is possible, certainly not one that will clearly and unambiguously delimit books, journals, magazines, newspapers, and any other print media, and also add electronicity without claiming blogs, RSS feeds, wikis, mail-lists, and website forums.[1] Each of these are distinct entities, yet might share every salient feature with most of the others at its margins.

I will instead go after What is our notion of a book? What is it I expect you to mean when you use that word instead of, say, “magazine” or “website”? [2]

So let us begin with this: “A book is something you read.” And by that we will not mean something we watch or view. [3]

While in a sense we have passed the buck to another philosophical discussion — What constitutes reading? — this allows us to now regard children’s books as entries into reading, and not annotated drawings. Moreover we have escaped making some arbitrary rules about the proportion of words to drawing or whether the artwork “illustrates” the text and such like.

Now saying a book is something you read means I regard a book of photographs as a book only in how I approach it psychologically based on its physical presentation. Remove the binding literally and figuratively and the book is no more — a slideshow of Ansel Adams photographs is no more a book [4] than it is a newspaper. The essence of book has expired along with the physical book.

And this starts us down a different path to answering our question of “What is a book?” If I can’t define a book the way I might define a hammer or an element in the periodic table or a songbird, I can at least identify characteristics or expectations that we all generally associate with a book. What results is less a definition in the dictionary sense than it is a diagnosis — any object meeting a majority of these symptoms will fall under our designation of “book,” even though other objects share some traits and not every trait is met by every instance.

So. What do we know about a book? Let us look at the general knowledge about books, the type that we use daily to distinguish books from other text media, as well as separating it from other media generally and from other artforms.

Like that famous dictum about obscenity from Potter Stewart, when he wrote that he might not be able to provide a test for it, “but I know it when I see it,” we must be guided by our intuition. Some aspects can change radically if the essence of the book is still recognizable. When we ask, What is a book? we know any answer will be slippery but our certainty is unwavering. In our test, it requires only that we remember the greater part of any book resides not in the physical, but in the invisible world. Then whether we have one author or a collaboration, unchanging text or mutable, physical pages or electronic, static images or dynamic, audio, video, connection to the web or not, whatever the manifestation the future brings us, there should be no confusion. Then as now, each of us will know a book when we see it.

[1] In part my conclusion of indefinability is based on similar effort undertaken years ago, when I was in graduate school. One professor set the students in his seminar to define what a poem was. As we attributed features to “a poem,” it was not hard to find counter examples — I remember a Thomas Wolfe sample brought in to counter the notion that rhythm distinguished poetry from prose. Language, purpose, length, rhythm, meter, rhyme, fixed patterns, brevity of expression — every feature could be countered with a prose sample that met the criteria and poems (which we all agreed were poems) that did not. Although we each had a notion of what constitutes a poem, we couldn’t create a definition that encompassed the essence of those notions.

What we settled on was the most rudimentary of differentiation, and yet unassailable — a poem is a text in which the author has decided where one line ends and the next begins.

[2] For instance, FTrain, a site written by Paul Ford in multiple voices, using multiple personae/bylines, mixing pieces that are not always obviously differentiable as being fiction, biography or memoir, as well as essay and reporting, and not incidentally relying on original musical compositions for full comprehension of the site.

[3] The audio book by this taxonomy is the platypus of content. Yes, it is a book. And yet we say mammals do not have bills and birds do, despite the contrary example of the platypus. Of course, the matter of illustrations, footnotes, maps, charts and such that we often utilize in a book do not fit so well in the audio book, so it is indeed an odd duck.

[4] It may come as a surprise that the contrary question of “Is a slideshow of The Castle a book?” is not that readily answered. It may well be. Assuming we are not seeing it formatted in Powerpoint bullets, the distinction between the pages of one of today’s e-books and a “slide” in that slideshow seems minuscule, one of projection onto a wall instead of display on a handheld device or computer. But the cohesiveness a binding provides those Ansel Adams photographs is more than matched in a novel by the linearity of the text, the consecutiveness of the sentences, the structure of a story being told. Without a binding, the photographs stand on their own, independent despite their sequence. Not so the text, where each page connects to its predecessor and successor. If we are to rule that a slideshow is not a book — not even a group-read book — it will have to be because it fails the criteria discussed later on.

[5] I repeat a famous observation noting how immediately in a crowded room we find someone’s eyes resting on us, and how small the actual visual information is, a fraction of a fraction of one percent of all that is visible to our eyes. Yet we scarcely recognize that we are the most visual of creatures.

[6 ] In his report that launched the Microsoft Reader, published as “The Magic of Reading.” [link to .lit version. To .doc version.]

[7] In his classic book, The Rhetoric of Fiction, another book I encountered first in graduate school.

I was startled but not surprised to read about John Updike’s denigration of the future of ebooks at BookExpo. Had he tattooed it on his forehead he couldn’t have made clearer his idealization of 19th-century structures and modes of thinking. His talk represented the final glorification of the author/artist/creator as a higher being ingrained with heroic capabilities unapproachable by mere mortals. For Updike and all those unable to cross into the new Canaan of electronicity, the apotheosis of the artist fits into the tradition of history as a history of heroes. There are but a few gods of literature as is only natural, I expected him to say, and if you have art made by whole masses of people, many of them unidentifiable, we’ll have regressed to the period of Notre Dame cathedral or the Pyramids, in which no individuals were glorified for their contributions to art or to the era when writing went unsigned or when the writer assumed the mantle of some greater person, to glorify them and spread their thinking.*

I was startled but not surprised to read about John Updike’s denigration of the future of ebooks at BookExpo. Had he tattooed it on his forehead he couldn’t have made clearer his idealization of 19th-century structures and modes of thinking. His talk represented the final glorification of the author/artist/creator as a higher being ingrained with heroic capabilities unapproachable by mere mortals. For Updike and all those unable to cross into the new Canaan of electronicity, the apotheosis of the artist fits into the tradition of history as a history of heroes. There are but a few gods of literature as is only natural, I expected him to say, and if you have art made by whole masses of people, many of them unidentifiable, we’ll have regressed to the period of Notre Dame cathedral or the Pyramids, in which no individuals were glorified for their contributions to art or to the era when writing went unsigned or when the writer assumed the mantle of some greater person, to glorify them and spread their thinking.*

This hero worship that Updike has wallowed in for the last 40 years has addled his brain. Reading some of his remarks reminded me of a screed published in the Saturday Review of Literature back in the 1970’s, if memory serves, by Louis Untermeyer, decrying the abominably inadequate generation of poets who couldn’t use rhyme or rhythm to make their way out of a paperbag. The rant was entertaining and almost credible in its denunciations — except for Untermeyer’s having chosen one of the great poems of the 20th century — Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died” — as his example of the witless drivel this shiftless new generation was producing. Untermeyer and Updike belong to the same class of critic as the French academicians who dismissed the Impressionists or the Fauves (“wild beasts”), blind to the future and in love with their own tinny emulation of the greater artists who preceded them. (Who will put Updike in the same list as Tolstoy or Faulkner or Fielding or Isak Dinesen? They made new forms, indelibly, while the best that can be said of Updike is that he stood alone as a prolific writer of magazine pieces.)

It’s been said** that new scientific theories don’t win over their opponents so much as they are accepted by the new generation and the old generation dies off. The same holds true in art, of course. The precocious writers of the coming generation will cut their teeth on blogs and networked books and media that will require visual acuity and improvisational methods that make Updike’s juvenilia*** feel as antiquated as William Dean Howells or James Fenimore Cooper. A living fossil. What a fall from the pantheon he occupies in his imagination.

* I’m thinking specifically of the authors of Revelations and several of the Gnostic gospels.

** Apparently most authoritatively in Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Updike’s remarks provide striking evidence of Kuhn’s theory of incommensurability of paradigms — if you are fully caught up in the old paradigm you have no way of assessing the new, lacking common values, language and experience with its proponents.

*** Updike has published, what, 36 books of fiction? We’ll be generous and include the first quarter in this categorization.

The Times yesterday ran a pretty decent article, “Digital Publishing Is Scrambling the Industry’s Rules”, discussing some recent experiments in book publishing online. One we’ve discussed here previously, Yochai Benkler’s The Wealth of Networks, which is available as both a hefty 500-page brick from Yale University Press and in free PDF chapter downloads. There’s also a corresponding readers’ wiki for collective annotation and discussion of the text online. It was an adventurous move for an academic press, though they could have done a better job of integrating the text with the discussion (it would have been fantastic to do something like GAM3R 7H30RY with Benkler’s book).

The Times yesterday ran a pretty decent article, “Digital Publishing Is Scrambling the Industry’s Rules”, discussing some recent experiments in book publishing online. One we’ve discussed here previously, Yochai Benkler’s The Wealth of Networks, which is available as both a hefty 500-page brick from Yale University Press and in free PDF chapter downloads. There’s also a corresponding readers’ wiki for collective annotation and discussion of the text online. It was an adventurous move for an academic press, though they could have done a better job of integrating the text with the discussion (it would have been fantastic to do something like GAM3R 7H30RY with Benkler’s book).

Also discussed is the new Mark Danielewski novel. His first book, House of Leaves, was published by Pantheon in 2000 after circulating informally on the web among a growing cult readership. His sophmore effort, due out in September, has also racked up some pre-publication mileage, but in a more controlled experiment. According to the Times, the book “will include hundreds of margin notes listing moments in history suggested online by fans of his work who have added hundreds of annotations, some of which are to be published in the physical book’s margins.” Annotations were submitted through an online forum on Danielewski’s web site, a forum that does not include a version of the text (though apparently 60 “digital galleys” were distributed to an inner circle of devoted readers).

The Times piece ends with an interesting quote from Danielewski, who, despite his roots in networked samizdat, is still ultimately focused on the book as a carefully crafted physical reading experience:

Mr. Danielewski said that the physical book would persist as long as authors figure out ways to stretch the format in new ways. “Only Revolutions,” he pointed out, tracks the experiences of two intersecting characters, whose narratives begin at different ends of the book, requiring readers to turn it upside down every eight pages to get both of their stories. “As excited as I am by technology, I’m ultimately creating a book that can’t exist online,” he said. “The experience of starting at either end of the book and feeling the space close between the characters until you’re exactly at the halfway point is not something you could experience online. I think that’s the bar that the Internet is driving towards: how to further emphasize what is different and exceptional about books.”

Fragmented as our reading habits (and lives) have become, there’s a persistent impulse, especially in fiction, toward the linear. Danielewski is probably right that the new networked modes of reading and writing might serve to buttress rather than unravel the old ways. Playing with the straight line (twisting it, braiding it, chopping it) is the writer’s art, and a front-to-end vessel like the book is a compelling restraint in which to work. This made me think of Anna Karenina, which is practically two novels braided together, the central characters, Anna and Levin, meeting just once, and then only glancingly.

I prefer to think of the networked book not as a replacement for print but as a parallel. What’s particularly interesting is how the two can inform one another, how a physical book can end up being changed and charged by its journey through a networked process. This certainly will be the case for the two books in progress the Institute is currently hosting, Mitch Stephens’ history of atheism and Ken Wark’s critical theory of video games. Though the books will eventually be “cooked” by a print publisher — Carroll & Graf, in Mitch’s case, and a university press (possibly Harvard or MIT), in Ken’s — they will almost certainly end up different for their having been networkshopped. Situating the book’s formative phase in the network can further boost the voltage between the covers.

An analogy. The more we learn about the evolution of biological life, the more we understand that the origin of species seldom follows a linear path. There’s a good deal of hybridization, random mutation, and general mixing. A paper recently published in Nature hypothesizes that the genetic link between humans and chimpanzees is at least a million years more recent than had previously been thought based on fossil evidence. The implication is that, for millennia, proto-chimps and proto-humans were interbreeding in a torrid cross-species affair.

An analogy. The more we learn about the evolution of biological life, the more we understand that the origin of species seldom follows a linear path. There’s a good deal of hybridization, random mutation, and general mixing. A paper recently published in Nature hypothesizes that the genetic link between humans and chimpanzees is at least a million years more recent than had previously been thought based on fossil evidence. The implication is that, for millennia, proto-chimps and proto-humans were interbreeding in a torrid cross-species affair.

Eventually, species become distinct (or extinct), but for long stretches it’s a story of hybridity. And so with media. Things are not necessarily replaced, but rather changed. Photography unleashed Impressionism from the paint brush; television, as Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s new book argues, acted as a foil for the postmodern American novel. The blog and the news aggregator may not kill the newspaper, but they will undoubtedly change it. And so the book. You see that glint in the chimp’s eye? A period of interbreeding has commenced.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of reader collaboration, prior to GAM3R TH3ORY‘s publication but to a good deal in response to its impending arrival. This notion clearly means that after the author has done one thing, the “book” becomes the accumulation of author’s and readers’ contributions.

So I’ve been thinking about collaboration. My starting point was something mentioned on my visit to the Institute — that the book’s source needs to be distributed, and it can be altered by the reader. (This is a very big idea, btw, and it’s radically altered my notion of what an e-book format’s obligations are. But that’s another discussion.)

SInce Sophie is an authoring tool, I thought, Why don’t I author something and really see what it can do? So I’ve been working with my own notion of what a book would be like that isn’t wholly limited by its medium being print. And I thought maybe I should let Sophie’s developers in on my ambition so that there’s a possibility that the features I’m envisioning might be included in the program, at least at some point in the future.

I think it’s easiest to understand my notion of collaborating with the reader by describing my work-in-progress.

So the basic notion is fairly simple, realizable already in Flash, say, or SVG:

Imagine a story, with multiple tracks. (I’m actually envisioning a short book, so let’s say 16 or 24 pages and 5 tracks.) On any page, you can go to the next or previous page. Or you can change tracks and see the next or previous page from some other track. It seems just like a 24-page book, except that the 5 tracks provide variations on what is on each page.

That’s not too exotic. And I don’t stray too far from this notion.

The first thing I’d like to do is provide multiple series of illustrations for each track. So track A might display what i call the French illustrations, or the English, or the Klee, and so on. Thus the first capability I would want to see in my authoring/reading tool is a way to change which illustration (or series of illustrations) displays within each track. You still go backwards and forwards, but maybe I like Van Gogh’s illustrations and you like Ansel Adams’. Perhaps I should mention at this point that it’s a children’s book, so I’m not casually speaking about illustrations. They are the central aspect.

The next thing I’d like to do is to allow the reader to supply illustrations, for any page (in any track), and supplant the author’s (or publisher’s) illustrations. So that perhaps my book comes with 4 series of illustrations for each track, but a reader could add many others. If these series were shared (upload your own, download others’), then perhaps you have 9 series for track A and I have 23. There has to be an easy way for the plugging in pieces, which is more on the level I’m expecting a reader to manage, as opposed to the full set of tools the author will access.

With this, the collaboration with the reader becomes two-fold — first the creation can be shared: make your own illustrations. Then, second, each individual instance becomes distinctive. If we trade “copies,” then we see the distinctive choices we each have made. Each instance is unique, especially as it contains series of illustrations that are not shared/distributed at all. In a way this reminds me of the trading card games that my ten-year-old and his friends play. They all purchase the same cards, each possessing hundreds of cards, and collect them into unique decks that they each admire and study (and then compete against, the duel being paramount). Moreover, each has some cards that none of the others has.

In addition to accepting individual illustrations or whole series of illustrations, the book should allow its text to be edited and alternate versions selected for display. I’m not sure whether one text track would be read-only, or if clicking some button would restore the text to its default form in some track, but I’d expect the author’s initial, unedited version should be retrievable in some way.

I’m far less concerned about the text than I am about this capability with illustrations, btw.

Since my project book is intended for children, I’ve thought a lot about the nature of collaboration with them. In this instance, I think will use little or no animation — it’s not an equal collaboration if the initiating author can do tricks to gain attention that the collaborating reader cannot manage. And that is one thing that makes this a book and not an animation or a cartoon and yet still strives to keep its electronicity high.

And my effort at collaboration is more like a teacher’s — here, you write/draw something, and we’ll replace what I’ve done. Perhaps in the end all the words and pictures are yours. My role was to get you started and to provide the framework. But every new collaborator can begin with the pristine master copy that anyone can access (or maybe they’ll start with a local, already altered variant that the teacher gives them). It hasn’t escaped my notice that in fact the collaboration might be between author and a class of students, not just one reader.

So. Likely as not, this first version of Sophie won’tt contain this addition/substitution capability, or perhaps not to the extent I describe. But I hope it can be added to the future feature set, or hooks anyway that will enable some plug-in to provide this capability. Because this type of collaboration seems to me to be essential.

* * *

It seems a natural expectation that a book constructed of multiple units might have multiple paths through it.

In the case of this children’s book, I don’t expect that going from track-A-page-1 to D3 to B4, and so on, is going to provide anything useful.

But I can clearly envision publications — a guidebook, a cookbook, a college course schedule, an anthology of poetry, a collection of photographs, the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, the Sayings of the Desert Fathers — in which a reader (or a teacher) may beneficially provide paths that an author overlooks. (Each of these examples of course is an instance of wholly independent units.)

In fact, I expect that Sophie’s envisioneers have thought of such circumstances already, but I raise it here as a collateral issue — collaboration with the reader must inevitably involve everything an author touches: the text, the development of the ideas, the sequence in which they are conveyed, how they are illustrated, the conclusions drawn. In a true collaboration, the author becomes something more like a director, operating perhaps at a remove (how active will the author be in reshaping the book after its publication?). Or maybe the director analogy is too strong; perhaps it’s more like an organizer — the Merry Pranksters, Christo, Lev Waleska — who launches his/her book like a vehicle (like Voyager) and then simply rides its momentum.

Once we make the book more collaborative, we remake what it means to author a book, and the creation of a book itself may come to be something more like a play or a movie or a dance, with multiple, recognized contributors.

I’m wondering how far Sophie goes in anticipating these ideas.

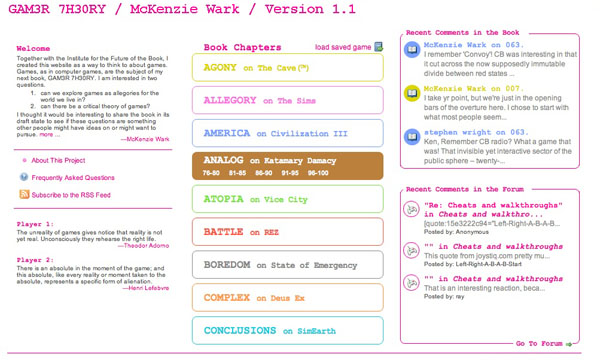

The Institute has published its first networked book, GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1 by McKenzie Wark! This is a fascinating look at video games as allegories of the world we live in, and (we think) a compelling approach to publishing in the network environment. As with Mitch Stephens’ ongoing experiment at Without Gods, we’re interested here in a process-oriented approach to writing, opening the book up to discussion and debate while it’s still being written.

Inside the book, you’ll find comment streams adjacent to each individual paragraph, inviting readers to respond to the text on a fine-grained level. Doing the comments this way (next to, not below, the parent posts) came out of a desire to break out of the usual top-down hierarchy of blog-based discussion — something we’ve talked about periodically here. There’s also a free-fire forum where people can start their own threads about the games dealt with in the book or about the experience of game play in general. It’s also a place to tackle meta-questions about networked books and to evaluate the successes and failings of our experiment. The gateway to the forum is a graphical topic pool in which conversations float along axes of time and quantity, giving a sense of the shape of the discussion.

Both sections of GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1 — the book and the forum — are designed to challenge current design conventions and to generate thoughtful exchange on the meaning of games. McKenzie will actively participate in these discussions and draw upon them in subsequent drafts of his book. The current version is published under a Creative Commons license.

And like the book, the site is a work in progress. We fully intend to make modifications and add new features as we go. Here’s to putting theory into practice!

(You can read archived posts documenting the various design stages of GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1 here.)