New partners and new features. Google has been busy lately building up Book Search. On the institutional end, Ghent, Lausanne and Mysore are among the most recent universities to hitch their wagons to the Google library project. On the user end, the GBS feature set continues to expand, with new discovery tools and more extensive “about” pages gathering a range of contextual resources for each individual volume.

Recently, they extended this coverage to books that haven’t yet been digitized, substantially increasing the findability, if not yet the searchability, of thousands of new titles. The about pages are similar to Amazon’s, which supply book browsers with things like concordances, “statistically improbably phrases” (tags generated automatically from distinct phrasings in a text), textual statistics, and, best of all, hot-linked lists of references to and from other titles in the catalog: a rich bibliographic network of interconnected texts (Bob wrote about this fairly recently). Google’s pages do much the same thing but add other valuable links to retailers, library catalogues, reviews, blogs, scholarly resources, Wikipedia entries, and other relevant sites around the net (an example). Again, many of these books are not yet full-text searchable, but collecting these resources in one place is highly useful.

It makes me think, though, how sorely an open source alternative to this is needed. Wikipedia already has reasonably extensive articles about various works of literature. Library Thing has built a terrific social architecture for sharing books. There are a great number of other freely accessible resources around the web, scholarly database projects, public domain e-libraries, CC-licensed collections, library catalogs.

Could this be stitched together into a public, non-proprietary book directory, a People’s Card Catalog? A web page for every book, perhaps in wiki format, wtih detailed bibliographic profiles, history, links, citation indices, social tools, visualizations, and ideally a smart graphical interface for browsing it. In a network of books, each title ought to have a stable node to which resources can be attached and from which discussions can branch. So far Google is leading the way in building this modern bibliographic system, and stands to turn the card catalogue of the future into a major advertising cash nexus. Let them do it. But couldn’t we build something better?

Category Archives: ebooks

samizdat express

In his latest NY Times column, Edward Rothstein meditates on the vastness of the public domain and the pleasures of skimming it in simple digital editions prepared by B+R Samizdat Express. Since 1993 B+R, run by Barbara and Richard Seltzer of West Roxbury, Massachusetts, has been selling bundles of plain text (ASCII) digital literature scooped from Project Gutenberg and arranged by theme, genre or period into anthologies — first on floppy disc, and now on CD-ROM and DVD. It’s all stuff you can get for free by grazing the web’s various public domain repositories, but B+R have done the work of harvesting and sorting and they’ll ship these multi-shelf-spanning chunks to you for the price of a single print volume. Browse through nearly 200 book collections they’ve assembled so far and you’ll find packages ranging from “Anthropology and Myth” ($19), “Works of Guy de Maupassant” ($12), or “The American Revolution and Early Republic as witnessed by Mercy Warren and Others” ($19). Some works are provided in audio through text-to-voice conversion software.

As Rothstein notes, the bare-bones formatting and sheer volume of the anthologies makes these works hard to digest, but there’s no doubt B+R provides a valuable service, especially for people in places where books are scarce and net access unreliable. All in all, it’s an e-book advocate’s playground but more of a hallucinogenic head trip for the average reader — a way to sample vastness. It does make one’s wheels start to turn, though, on what other elucidating layers could be built on top of the vast murk of the digital library.

dismantling the book

Peter Brantley relates the frustrating experience of trying to hunt down a particular passage in a book and his subsequent painful collision with the cold economic realities of publishing. The story involves a $58 paperback, a moment of outrage, and a venting session with an anonymous friend in publishing. As it happens, the venting turned into some pretty fascinating speculative musing on the future of books, some of which Peter has reproduced on his blog. Well worth a read.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

Amazon already provides a by-the-page or by-the-chapter option for certain titles through its “Pages” program. Google presumably will hammer out some deals with publishers and offer a similar service before too long. Peter Osnos’ Caravan Project includes individual chapter downloads and print-on-demand as part of the five-prong distribution standard it is promoting throughout the industry. If this catches on, it will open up a plethora of options for readers but it might also unvravel the very notion of what a book is. Could we be headed for a replay of the mp3’s assault on the album?

The wholeness of the book has to some extent always been illusory, and reading far more fragmentary than we tend to admit. A number of things have clouded our view: the economic imperative to publish whole volumes (it’s more cost-effective to produce good aggregations of content than to publish lots of individual options, or to allow readers to build their own); romantic notions of deep, cover-to-cover reading; and more recently, the guilty conscience of the harried book consumer (when we buy a book we like to think that we’ll read the whole thing, yet our shelves are packed with unfinished adventures).

But think of all the books that you value just for a few particular nuggets, or the books that could have been longish essays but were puffed up and padded to qualify as $24.95 commodities (so many!). Any academic will tell you that it is not only appropriate but vital to a researcher’s survival to hone in on the parts of a book one needs and not waste time on the rest (I’ve received several tutorials from professors and graduate students on the fine art of fileting a monograph). Not all thoughts are book-sized and not all reading goes in a straight line. Selective reading is probably as old as reading itself.

Unbundling the book has the potential to allow various forms of knowledge to find the shapes and sizes that fit them best. And when all the pieces are interconnected in the network, and subject to social discovery tools like tagging, RSS and APIs, readers could begin to assume a role traditionally played by publishers, editors and librarians — the role of piecing things together. Here’s the bit of Peter’s conversation that goes into this:

Peter: …the Google- empowered vision of the “network of books” which is itself partially a romantic, academic notion that might actually be a distinctly net minus for publishers. Potentially great for academics and readers, but potentially deadly for publishers (not to mention librarians). As opposed to the simple first order advantage of having the books discoverable in the first place – but the extent to which books are mined and then inter-connected – that is an interesting and very difficult challenge for publishers.

Am I missing something…?

Friend: If you mean, are book publishers as we know them doomed? Then the answer is “probably yes.” But it isn’t Google’s connecting everything together that’s doing it. If people still want books, all this promotion of discovery will obviously help. But if they want nuggets of information, it won’t. Obviously, a big part of the consumer market that book publishers have owned for 200 years want the nuggets, not a narrative. They’re going, going, gone. The skills of a “publisher” — developing content and connecting it to markets — will have to be applied in different ways.

Peter: I agree that it is not the mechanical act of interconnection that is to blame but the demand side preference for chunks of texts. And the demand is probably extremely high, I agree.

The challenge you describe for publishers – analogous in its own way to that for libraries – is so fundamentally huge as to mystify the mind. In my own library domain, I find it hard to imagine profoundly differently enough to capture a glimpse of this future. We tinker with fabrics and dyes and stitches but have not yet imagined a whole new manner of clothing.

Friend: Well, the aggregation and then parceling out of printed information has evolved since Gutenberg and is now quite sophisticated. Every aspect of how it is organized is pretty much entirely an anachronism. There’s a lot of inertia to preserve current forms: most people aren’t of a frame of mind to start assembling their own reading material and the tools aren’t really there for it anyway.

Peter: They will be there. Arguably, when you look at things like RSS and Yahoo Pipes and things like that – it’s getting closer to what people need.

And really, it is not always about assembling pieces from many different places. I might just want the pieces, not the assemblage. That’s the big difference, it seems to me. That’s what breaks the current picture.

Friend: Yes, but those who DO want an assemblage will be able to create their own. And the other thing I think we’re pointed at, but haven’t arrived at yet, is the ability of any people to simply collect by themselves with whatever they like best in all available media. You like the Civil War? Well, by 2020, you’ll have battle reenactments in virtual reality along with an unlimited number of bios of every character tied to the movies etc. etc. etc. I see a big intellectual change; a balkanization of society along lines of interest. A continuation of the breakdown of the 3-television network (CBS, NBC, ABC) social consensus.

follow the eyes: screenreading reconsidered (again)

From Editor&Publisher (via Print is Dead): The Poynter Institute just released findings from a study in which eye-tracking sensors were used to analyze the behavior of 600 readers across print and online news sources. The resulting data clashes with the usual assumptions:

When readers chose to read an online story, they usually read an average of 77% of the story, compared to 62% in broadsheets and 57% in tabloids…

The study looked at two tabloids, the Rocky Mountain News and Philadelphia Daily News; two broadsheets, the St. Petersburg Times and The Star-Tribune of Minneapolis; and two newspaper Web sites, at the Times and Star-Tribune.

Considering the increasingly disaggregated nature of people’s news-sifting, is “two newspaper websites” really the right test bed for gauging online reading habits? Still, this is a pretty interesting, myth-busting find, though in a way not at all surprising.

This takes us back to the discussion around Cory Doctorow’s recent piece betting on the long-term persistence of print for certain kinds of reading. Print reading, he says, tends toward the sustained and immersive, the long-form linear narrative. Computer reading, on the other hand, is multi-tasky — distracted, social, bite-sized, multidirectional. One could poke a lot of holes in these characterizations, but generally speaking, they do sum up the way in which many of us divide our reading labor (and leisure) across “platforms.” Contrary to popular belief, Doctorow argues, people do like reading on screens. But they also like reading from printed pages. It’s not either/or — the different modes of reading reinforce the different modes of conveyance, paper and PC.

I’ve tended to agree, but many of the folks in the comments here didn’t. They insisted that it’s only a matter of time before we’ll be doing the vast majority of our reading on screens — even the linear, immersive reading that seems most resistant to digital migration. Getting past my own deep attachment to print, and reckoning with how far into daily practice electronic reading has already penetrated in so little time, I have to admit that this is probably true, though I imagine print will likely persist for at least a few more generations, and will always have its uses (and will hopefully be kept as a contingency reserve in case the lights go out).

Ultimately, this is a boring game, betting on which technology will win out. But it’s interesting sometimes to analyze what motivates certain big cultural actors to wager the way they do.

If you think about it, it makes a lot of sense that Doctorow, generally an advocate for new technologies, wants to see print survive, and why despite his progressive edge, he’s a bit of a traditionalist. As a novelist, Doctorow is deeply invested in the economic model of print. That’s the way he actually sells books (and probably the way he likes to read them). And yet he grasps the Internet’s potential to leverage print — his career as a writer took off at precisely the moment when these two worlds entered into a complex symbiosis. As such, he has long been evangelizing the practice of giving away e-books to sell more print books, pointing to his own great success as proof of the hybrid concept.

At the surreal Google conference I attended at the New York Public Library in January, Doctorow took the stage as mollifier-in-chief, soothing the gathered representatives of the publishing industry with assurances that print is here to stay, is in fact reinforced by new online discovery tools like Google Book Search and free e-versions (which he suggests are used primarily for browsing or “market research”). All of this is right and true — for now — and Doctorow’s advice to publishers to loosen up and embrace the Web as a gateway toward offline reading experiences, and as a way to socially situate their texts on the network is good advice, but it doesn’t necessarily shed light on the longer term. The Poynter study, in its crude way, does.

Net-native writing will always be for a distracted audience, print for a captivated one, says Doctorow. He’s comfortable with that split. And I guess I’ve been too, suggesting as it does two sorts of knowledge, neither of which we’d want to lose. But the gap will almost certainly narrow, and figuring out the consequences of that is certainly one of our biggest challenges.

screenreading reconsidered

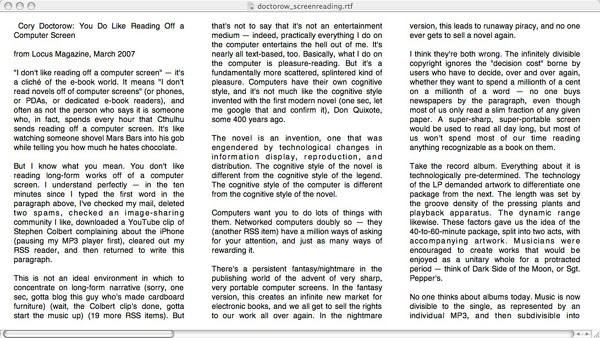

There’s an interesting piece by Cory Doctorow in Locus Magazine, a sci-fi and fantasy monthly, entitled “You Do Like Reading Off a Computer Screen.” discussing the differences between on and offline reading.

The novel is an invention, one that was engendered by technological changes in information display, reproduction, and distribution. The cognitive style of the novel is different from the cognitive style of the legend. The cognitive style of the computer is different from the cognitive style of the novel.

Computers want you to do lots of things with them. Networked computers doubly so — they (another RSS item) have a million ways of asking for your attention, and just as many ways of rewarding it.

And he illustrates his point by noting throughout the article each time he paused his writing to check an email, read an RSS item, watch a YouTube clip etc.

I think there’s more that separates these forms of reading than distracted digital multitasking (there are ways of reading online reading that, though fragmentary, are nonetheless deep and sustained), but the point about cognitive difference is spot on. Despite frequent protestations to the contrary, most people have indeed become quite comfortable reading off of screens. Yet publishers still scratch their heads over the persistent failure of e-books to build a substantial market. Befuddled, they blame the lack of a silver bullet reading device, an iPod for books. But really this is a red herring. Doctorow:

The problem, then, isn’t that screens aren’t sharp enough to read novels off of. The problem is that novels aren’t screeny enough to warrant protracted, regular reading on screens.

Electronic books are a wonderful adjunct to print books. It’s great to have a couple hundred novels in your pocket when the plane doesn’t take off or the line is too long at the post office. It’s cool to be able to search the text of a novel to find a beloved passage. It’s excellent to use a novel socially, sending it to your friends, pasting it into your sig file.

But the numbers tell their own story — people who read off of screens all day long buy lots of print books and read them primarily on paper. There are some who prefer an all-electronic existence (I’d like to be able to get rid of the objects after my first reading, but keep the e-books around for reference), but they’re in a tiny minority.

There’s a generation of web writers who produce “pleasure reading” on the web. Some are funny. Some are touching. Some are enraging. Most dwell in Sturgeon’s 90th percentile and below. They’re not writing novels. If they were, they wouldn’t be web writers.

On a related note, Teleread pointed me to this free app for Macs called Tofu, which takes rich text files (.rtf) and splits them into columns with horizontal scrolling. It’s super simple, with only a basic find function (no serious search), but I have to say that it does a nice job of presenting long print-like texts. By resizing the window to show fewer or more columns you can approximate a narrowish paperback or spread out the text like a news broadsheet. Clicking left or right slides the view exactly one column’s width — a simple but satisfying interface. I tried it out with Doctorow’s piece:

I also plugged in Gamer Theory 2.0 and it was surprisingly decent. Amazing what a little extra thought about the screen environment can accomplish.

time out and some of what went into it

A remaindered link that I keep forgetting to post. A couple of weeks back, Time Out London ran a nice little “future of books” feature that makes mention of the Institute. A good chunk of it focuses on On Demand Books, the Espresso book machine and the evolution of print, but it also manages to delve a bit into networked territory, looking at Penguin’s wiki novel project and including a few remarks from me about the yuckiness of e-book hardware and the social aspects of text. Leading up to the article, I had some nice conversations over email and phone with the writer Jessica Winter, most of which of course had no hope of fitting into a ~1300-word piece. And as tends to be the case, the more interesting stuff ended up on the cutting room floor. So I thought I’d take advantage of our laxer space restrictions and throw up for any who are interested some of that conversation.

(Questions are in bold. Please excuse rambliness.)

The other day I was having an interesting conversation with a book editor in which we were trying to determine whether a book is more like a table or a computer; i.e., is a book a really good piece of technology in its present form, or does it need constant rethinking and upgrades, or is it both? Another way of asking this question: Will the regular paper-and-glue book go the way of the stone tablet and the codex, or will it continue to coexist with digital versions? (Sorry, you must get asked this question all the time…)

We keep coming back to this question is because it’s such a tricky one. The simple answer is yes.

The more complicated answer…

When folks at the Institute talk about “the book,” we’re really more interested in the role the book historically has played in our civilization — that is, as the primary vehicle humans use for moving around ideas. In this sense, it seems pretty certain that the future of the book, or to put it more awkwardly, the future of intellectual discourse, is shifting inexorably from printed pages to networked screens.

Predicting hardware is a tougher and ultimately less interesting pursuit. I guess you could say we’re agnostic: unsure about the survival or non-survival of the paper-and-glue book as we are about the success or failure of the latest e-book reading device to hit the market. Still, there’s this strong impulse to try to guess which forms will prevail and which will go extinct. But if you look at the history of media you find that things usually aren’t so clear cut.

It’s actually quite seldom the case that one form flat out replaces another. Far more often the two forms go on existing together, affecting and changing one other in a variety of ways. Photography didn’t kill painting as many predicted it would. Instead it caused a crisis that led to Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism. TV didn’t kill radio but it did usurp radio’s place at the center of the culture and changed the sorts of programming that it made sense for radio to deliver. So far the Internet hasn’t killed TV but there’s no question that it’s bringing about a radical shift in both the production and consumption of television, blurring the line between the two.

The Internet probably won’t kill off books either but it will almost certainly affect what sorts of books get produced, and on the ways in which we read and write them. It’s happening already. Books that look and feel much the same way today as they looked and felt 30 years ago are now almost invariably written on computers with word processing applications, and increasingly, researched or even written on the Web.

Certain things that we used to think of as books — encyclopedias, atlases, phone directories, catalogs — have already been reinvented, and in some cases merged. Other sorts of works, particularly long-form narratives, seem to have a more durable relationship with the printed word. But even here, our relationship with these books is changing as we become more accustomed to new networked forms. Continuous partial attention. Porous boundaries between documents and media. Social and participatory forms of reading. Writing in public. All these things change the very idea of reading and writing, so when you resume an offline mode of doing these things, your perceptions and way of thinking have likely changed.

(A side note. I think this experience of passage back and forth between off and online forms, between analog and digital, is itself significant and for people in our generation, with our general background, is probably the defining state of being. We’re neither immigrant or native. Or to dip into another analogical pot, we’re amphibians.)

As time and technology progress and we move with increasing fluidity between print and digital, we may come to better appreciate the unique affordances of the print book. Looked at one way, the book is an outmoded technology. It lacks the interactivity and interconnectedness of networked communication and is extremely limited in scope when compared with the practically boundless universe of texts and media that exists online. But you could also see this boundedness is its greatest virtue — the focus and structure it brings, enabling sustained thought and contemplation and private intellectual growth. Not to mention archival stability. In these ways the book is a technology that would be hard to improve upon.

John Updike has said that books represent “an encounter, in silence, of two minds.” Does that hold true now, or will it continue to as we continue to rethink the means of production (both technological and intellectual) of books? What are the advantages and disadvantages of a networked book over a book traditionally conceived in that “silent encounter”?

I think I partly answered this question in the last round. But again, as with media forms, so too with ways of reading. Updike is talking about a certain kind of reading, the kind that is best suited to the sorts of things he writes: novels, short stories and criticism. But it would be a mistake to apply this as a universal principle for all books, especially books that are intended as much, if not more, as a jumping off point for discussion as for that silent encounter.

Perhaps the biggest change being brought about by new networked forms of communication is the redefinition of the place of the individual in relation to the collective. The present publishing system very much favors the individual, both in the culture of reverence that surrounds authors and in the intellectual property system that upholds their status as professionals. Updike is at the top of this particular heap and so naturally he defends it as though it were the inviolable natural order.

Digital communication radically clashes with this order: by divorcing intellectual property from physical property (a marriage that has long enabled the culture industry to do business) and by re-situating textual communication in the network, connecting authors and readers in startling ways that rearrange the traditional hiearchies.

What do you think of print-on-demand technology like the Espresso machine? One quibble that I have with it, and it’s probably a lost cause, is that it seems part of the death of browsing (which is otherwise hastened by the demise of the independent bookstore and the rise of the “drive-through” library); opportunities for a chance encounter with a book seem to be lessened. Just curious–has the Institute addressed the importance of browsing at all?

The serendipity of physical browsing would indeed be unfortunate to lose, and there may be some ways of replicating it online. North Carolina State University uses software called Endeca for their online catalog where you pull up a record of a book and you can look at what else is next to it on the physical shelf. But generally speaking browsing in the network age is becoming a social affair. Behavior-derived algorithms are one approach — Amazon’s collaborative filtering system, based on the aggregate clickstreams and purchasing patterns of its customers, is very useful and getting better all the time. Then there’s social bookmarking. There, taxonomy becomes social, serendipity not just a chance encounter with a book or document, but with another reader, or group of readers.

And some other scattered remarks about conversation and the persistent need for editors:

Blogging, comments, message boards, etc… In some ways, the document as a whole is just the seed for the responses. It’s pointing toward a different kind of writing that is more dialogical, and we haven’t really figured it out yet. We don’t yet know how to manage and represent complex conversations in an electronic environment. From a chat room to a discussion forum to a comment stream in a blog post, even to an e-mail thread or a multiparty instant-messaging conversation–it’s just a list of remarks, a linear transcript that flattens the discussion’s spirals, loops and pretzels into a single straight line. In other words, the minute the conversation becomes complex, we become unable to make that complexity readable.

We’ve talked about setting up shop in Second Life and doing an experiment there in modeling conversations. But I’m more interested in finding some way of expanding two-dimensional interfaces into 2.5. We don’t yet know how to represent conversations on a screen once it crosses a certain threshold of complexity.

People gauge comment counts as a measure of the social success of a piece of writing or a video clip. If you look at Huffington Post, you’ll see posts that have 500 comments. Once it gets to that level, it’s sort of impenetrable. It makes the role of filters, of editors and curators–people who can make sound selections–more crucial than ever.

Until recently, publishing existed as a bottleneck model with certain material barriers to publishing. The ability to overleap those barriers was concentrated in a few bottlenecks, with editorial filters to choose what actually got out there. Those material barriers are no longer there; there’s still an enormous digital divide, but for the 1 billion or so people who are connected, those barriers are incredibly low. There’s suddenly a super-abundance of information with no gatekeeper; instead of a bottleneck, we have a deluge. The act of filtering and selecting it down becomes incredibly important. The function that editors serve in the current context will be need to be updated and expanded.

gamer theory 2.0 – visualize this!

Call for participation: Visualize This!

How can we ‘see’ a written text? Do you have a new way of visualizing writing on the screen? If so, then McKenzie Wark and the Institute for the Future of the Book have a challenge for you. We want you to visualize McKenzie’s new book, Gamer Theory.

How can we ‘see’ a written text? Do you have a new way of visualizing writing on the screen? If so, then McKenzie Wark and the Institute for the Future of the Book have a challenge for you. We want you to visualize McKenzie’s new book, Gamer Theory.

Version 1 of Gamer Theory was presented by the Institute for the Future of the Book as a ‘networked book’, open to comments from readers. McKenzie used these comments to write version 2, which will be published in April by Harvard University Press. With the new version we want to extend this exploration of the book in the digital age, and we want you to be part of it.

All you have to do is register, download the v2 text, make a visualization of it (preferably of the whole text though you can also focus on a single part), and upload it to our server with a short explanation of how you did it.

All visualizations will be presented in a gallery on the new Gamer Theory site. Some contributions may be specially featured. All entries will receive a free copy of the printed book (until we run out).

By “visualization” we mean some graphical representation of the text that uses computation to discover new meanings and patterns and enables forms of reading that print can’t support. Some examples that have inspired us:

- Brad Paley’s Text Arc

- Marcos Weskamp’s Newsmap

- Fernanda Viegas’ Wikipedia “History Flow”

- Chirag Mehta’s US Presidential Speeches Tag Cloud

- Kushal Dave’s Exegesis

- Magnus Rembold and Jurgen Spath’s comparative essay visualizations in Total Interaction

- Philip DeCamp, Amber Frid-Jimenez, Jethran Guiness, Deb Roy: “Gist Icons” (pdf)

- CNET News.com’s The Big Picture

- Visuwords online graphical dictionary

- Christopher Collins’ DocuBurst

- Stamen Design’s rendering of Kate Hayles’ Narrating Bits in USC’s Vectors

- Brian Kim Stefans’ The Dreamlife of Letters

- Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries

Understand that this is just a loose guideline. Feel encouraged to break the rules, hack the definition, show us something we hadn’t yet imagined.

All visualizations, like the web version of the text, will be Creative Commons licensed (Attribution-NonCommercial). You have the option of making your code available under this license as well or keeping it to yourself. We encourage you to share the source code of your visualization so that others can learn from your work and build on it. In this spirt, we’ve asked experienced hackers to provide code samples and resources to get you started (these will be made available on the upload page).

Gamer 2.0 will launch around April 18th in synch with the Harvard edition. Deadline for entries is Wednesday, April 11th.

Read GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1.

Download/upload page (registration required):

http://web.futureofthebook.org/gamertheory2.0/viz/

google makes slight improvements to book search interface

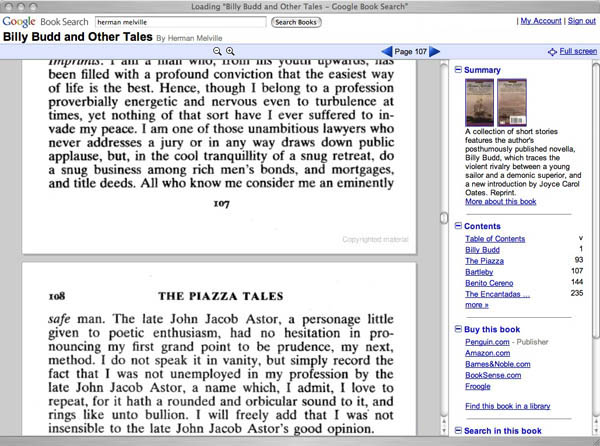

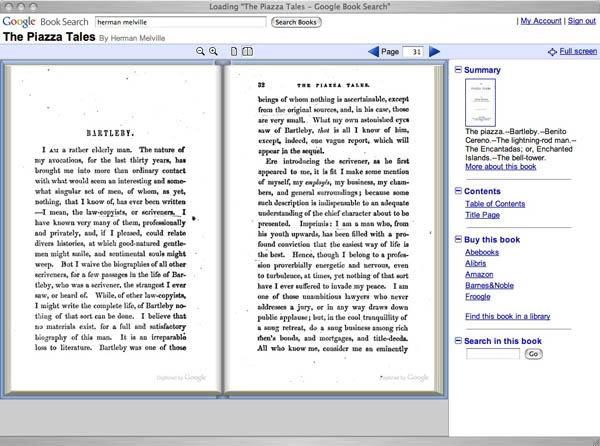

Google has added a few interface niceties to its Book Search book viewer. It now loads multiple pages at a time, giving readers the option of either scrolling down or paging through left to right. There’s also a full screen reading mode and a “more about this book” link taking you to a profile page with links to related titles plus references and citations from other books or from articles in Google Scholar. Also on the profile page is a searchable keyword cluster of high-incidence names or terms from the text.

Above is the in-copyright Signet Classic edition of Billy Budd and Other Tales by Melville, which contains only a limited preview of the text. You can also view the entire original 1856 edition of Piazza Tales as scanned from the Stanford Library. Public domain editions like this one can now be viewed with facing pages.

Still a conspicuous lack of any annotation or social reading tools.

electronic literature collection – vol. 1

Seven years ago, the Electronic Literature Organization was founded “to promote and facilitate the writing, publishing, and reading of electronic literature.” Yesterday marked a major milestone in the pursuit of the “reading” portion of this mission as ELO released the first volume of the Electronic Literature Collection, a wide-ranging anthology of 60 digital literary texts in a variety of styles and formats, from hypertext to Flash poetry. Now, for the first time, all are made easily accessible over the web or on a free CD-ROM, both published under a Creative Commons license.

The contents — selected by N. Katherine Hayles, Nick Montfort, Scott Rettberg and Stephanie Strickland — range from 1994 to the present, but are stacked pretty heavily on this side of Y2K. Perhaps this is due to the difficulty of converting older formats to the web, or rights difficulties with electronic publishers like Eastgate. Regardless, this is a valuable contribution and ELO is to be commended for making such a conscious effort to reach out to educators (they’ll send a free CD to anyone who wants to teach this stuff in a class). Hopefully volume two will delve deeper into the early days of hypertext.

This outreach effort in some ways implicitly acknowledges that this sort of literature never really found a wider audience, (unless you consider video games to be the new literature, in which case you might have a bone to pick with this anthology). Arguments have raged over why this is so, looking variously to the perishability of formats in a culture of constant system upgrades to more conceptual concerns about non-linear narrative. But whether e-literature fan or skeptic, this new collection should be welcomed as a gift. Bringing these texts back into the light will hopefully help to ground conversations about electronic reading and writing, and may inspire new phases of experimentation.

what we talk about when we talk about books

I spent the past weekend at the Fourth International Conference on the Book, hosted by Emerson College in Boston this year. I was there for a conversation with Sven Birkerts (author of The Gutenberg Elegies) which happened to kick off the conference. The two of us had been invited to discuss the future of the book, which is a great deal to talk about in an hour. While Sven was cast as the old curmudgeon and I was the Young Turk, I’m not sure that our positions are that dissimilar. We both value books highly, though I think my definition of book is a good deal broader than his. Instead of a single future of the book, I suggested that we need to be talking about futures of the book.

This conciliatory note inadvertently described the conference as a whole, the schedule of which can be inspected here. The subjects discussed wandered all over the place, from people trying to carry out studies on how well students learned with an ebook device to a frankly reactionary presentation of book art. Bob Young of Lulu proclaimed the value of print on demand for authors; Jason Epstein proclaimed the value of print on demand for publishers. Publishers wondered whether the recent rash of falsified memoirs would hurt sales. Educators talked about the need for DRM to encrypt online texts. There was a talk on using animals to deliver books which I’m very sorry that I missed. A Derridean examination of the paratexts of Don Quixote suggested out that for Cervantes, the idea of publishing a book – as opposed to writing one – suggested death, perhaps what I’d been trying to argue last week.

Everyone involved was dealing with books in some way or another; a spectrum could be drawn from those who were talking about the physical form of the book and those who were talking about content of the book entirely removed from the physical. These are two wildly different things, which made this a disorienting conference. The cumulative effect was something like if you decided to convene a conference on people and had a session with theologians arguing about the soul in one room while in another room a bunch of body builders tried to decide who was the most attractive. Similarly, everyone at the Conference on the Book had something to do with books; however, many people weren’t speaking the same language.

This isn’t necessarily their fault. One of the most apt presentations was by Catherine Zekri of the Université de Montréal, who attempted to decipher exactly what a “book” was from usage. She noted the confusion between the object of the book and its contents, and pointed out that this confusion carried over into the electronic realm, where “ebook” can either mean a device (like the Sony Reader) or the text that’s being read on the device. A thirty-minute session wasn’t nearly long enough to suss out the differences being talked about, and I’ll be interested to read her paper when it’s finally published.

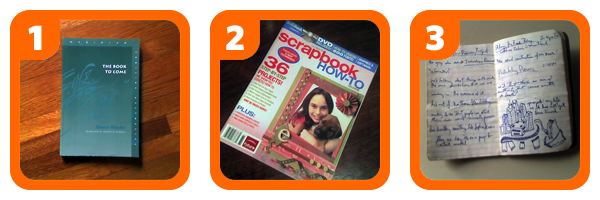

As an experiment paralleling Zekri’s, here are three objects:

There are certain similarities all of these objects share: they’re all made of paper and have a cover and pages. Some similarities are only shared by some of the objects: what’s the best way of grouping these? Three relationships seem possible. Objects 1 & 2 were bought containing text; object 3 was blank when bought, though I’ve written in it since. Objects 2 & 3 are bound by staples; object 1 is bound by glue. Objects 1 & 3 were written by a single person (Maurice Blanchot in the case of 1, myself in the case of 3); object 2 was written by a number people.

If we were to classify these objects, how would we do it? Linguistically, the decision has already been made: object 1 is a book, object 2 is a magazine, and object 3 is a notebook, which is, the Oxford English Dictionary says, “a small book with blank or ruled pages for writing notes in”. By the words we use to describe them, objects 1 & 3 are books. A magazine isn’t a book: it’s “a periodical publication containing articles by various writers” (the OED again). This is something seems intuitive: a magazine isn’t a book. It’s a magazine.

But why isn’t a magazine a book, especially if a notebook is a book? If you look again at the relationships I suggested between the three objects above, the shared attributes of the book and the magazine seem more logical and important than the attributes shared between the book and the notebook. Why don’t we think of a magazine as a book? To use the language of evolutionary biology, the word “book” seems to be a polyphyletic taxon, a group of descendants from a common ancestor that excludes other descendants from the same ancestor.

One answer might be that a single issue of a magazine isn’t complete; rather, it is part of a sequence in time, a sequence which can be called a magazine just as easily as a single issue can. I can say that I’ve read a book, which presumably means that I’ve read and understood every word in it. I can say the same thing about a particular issue of The Atlantic (“I read that magazine.”). I can’t say the same thing about the entire run of The Atlantic, which started long before I was born and continues today. A complete edition of The Atlantic might be closer to a library than a book. Or maybe the problem is time: the date on the cover foregrounds a magazine’s existence in time in a way that a book’s existence in time isn’t something we usually think about.

To expand this: I looked up these definitions in the online OED, where the dictionary exists as a database that can be queried. Is this a book? I have a single-volume OED at home with much the same content, though the online version has changed since the print edition: it points out that since 1983, the word “notebook” can also mean a portable computer. My copy of the OED at home is clearly a book; is the online edition, with its evolving content, also a book? (A stylistic question: we italicize the title of a book when we use it in text – do we italicize the title of a database?)

We’ve been calling things like Wikipedia, which goes even further than the online OED in terms of its mutability over time, a “networked book”. But even with much simpler online projects, issues arise: take Gamer Theory, for example. If much the content of what appears on the Gamer Theory website appears in Harvard University Press’s version of the book, most people would agree that the online version is a book, or a draft of one. But what are the boundaries of this kind of book? Are the comments in the website part of the book? Is the forum part of the book? Are the spam comments that we deleted from the forum part of the book? This also has something to do with Bob’s post on Monday, where he wondered how sharply defined the authorial voice of a book needs to be to make it worthwhile as a book.

What we have here is a language problem: the forms that we can create are evolving faster than our language – and possibly our understanding – can keep up with them.