Jimmy Wales believes that the Wikibooks project will do for the textbook what Wikipedia did for the encyclopedia; replacing costly printed books with free online content developed by a community of contributors. But will it? Or, more accurately, should it? The open source volunteer format works for encyclopedia entries, which don’t require deep knowledge of a particular subject. But the sustained examination and comprehensive vision required to understand and contextualize a particular subject area is out of reach for most wiki contributors. The communal voice of the open source textbook is also problematic, especially for humanities texts, as it lacks the power of an inspired authoritative narrator. This is not to say that I think open source textbooks are doomed to failure. In fact, I agree with Jimmy Wales that open source textbooks represent an exciting, liberating and inevitable change. But there are some real concerns that we need to address in order to help this format reach its full potential. Including: how to create a coherent narrative out of a chorus of anonymous voices, how to prevent plagiarism, and how to ensure superior scholarship.

To illustrate these points, I’m going to pick on a Wikibook called: Art History. This book won the distinction of “collaboration of the month” for October, which suggests that, within the purview of wikibooks, it represents a superior effort. Because space is limited, I’m only going to examine two passages from Chapter One, comparing the wikibook to similar sections in a traditional art history textbook. Below is the opening paragraph, framing the section on Paleolithic Art and cave paintings, which begins the larger story of art history.

Art has been part of human culture for millenia. Our ancient ancestors left behind paintings and sculptures of delicate beauty and expressive strength. The earliest finds date from the Middle Paleolithic period (between 200,000 and 40,000 years ago), although the origins of Art might be older still, lost to the impermanence of materials.

Compare that to the introduction given by Gardner’s Art Through the Ages (seventh edition):

What Genesis is to the biblical account of the fall and redemption of man, early cave art is to the history of his intelligence, imagination, and creative power. In the caves of southern France and of northern Spain, discovered only about a century ago and still being explored, we may witness the birth of that characteristically human capability that has made man master of his environment–the making of images and symbols. By this original and tremendous feat of abstraction upper Paleolithic men were able to fix the world of their experience, rendering the continuous processes of life in discrete and unmoving shapes that had identity and meaning as the living animals that were their prey.

In that remote time during the last advance and retreat of the great glaciers man made the critical breakthrough and became wholly human. Our intellectual and imaginative processes function through the recognition and construction of images and symbols; we see and understand the world pretty much as we were taught to by the representations of it familiar to our time and place. The immense achievement of Stone Age man, the invention of representation, cannot be exaggerated.

As you can see the wiki book introduction seems rather anemic and uninspired when compared to Gardner’s. The Gardner’s introduction also sets up a narrative arc placing art of this era in the context of an overarching story of human civilization.

I chose Gardner’s Art Through the Ages because it is the classic “Intro to Art History” textbook (75 years old, in its eleventh edition). I bought my copy in high school and still have it. That book, along with my brilliant art history teacher Gretchen Whitman, gave me a lifelong passion for visual art and a deep understanding of its significance in the larger story of western civilization. My tattered but beloved Gardner’s volume still serves me well, some 20 odd years later. Perhaps it is the beauty of the writing, or the solidity of the authorial voice, or the engaging manner in which the “story” of art is told.

Let’s compare another passage; this one describes pictorial techniques employed by stone age painters. First the wikibook:

Another feature of the Lascaux paintings deserves attention. The bulls there show a convention of representing horns that has been called twisted perspective, because the viewer sees the heads in profile but the horns from the front. Thus, the painter’s approach is not strictly or consistently optical. Rather, the approach is descriptive of the fact that cattle have two horns. Two horns are part of the concept “bull.” In strict optical-perspective profile, only one horn would be visible, but to paint the animal in that way would, as it were, amount to an incomplete definition of it.

And now Gardner’s:

The pictures of cattle at Lascaux and elsewhere show a convention of representation of horns that has been called twisted perspective, since we see the heads in profile but the horns from a different angle. Thus, the approach of the artist is not strictly or consistently optical–that is, organized from a fixed-viewpoint perspective. Rather, the approach is descriptive of the fact that cattle have two horns. Two horns would be part of the concepts “cow” or “bull.” In a strict optical-perspective profile only one horn would be visible, but to paint the animal in such a way would, as it were, amount to an incomplete definition of it.

This brings up another very serious problem with open-source textbooks–plagiarism. If the first page of the wikibook-of-the month blatantly rips-off one of the most popular art history books in print and nobody notices, how will Wikibooks be able to police the other 11,000 plus textbooks it intends to sponsor? What will the consequences be if poorly written, plagairized, open-source textbooks become the runaway hit that Wikibooks predicts?

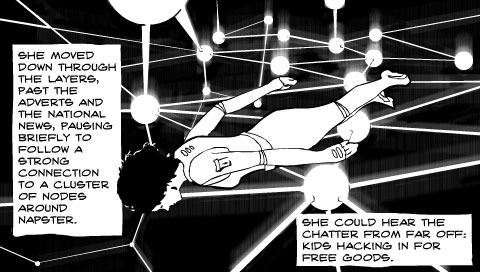

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year). Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

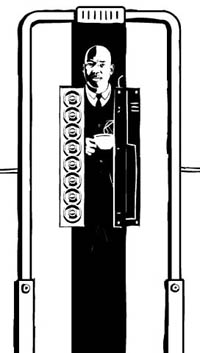

As for the device, well, the

As for the device, well, the