Chatting with someone from Random House’s digital division on the day of the Kindle release, I suggested that dramatic price cuts on e-editions -? in other words, finally acknowledging that digital copies aren’t worth as much (especially when they come corseted in DRM) as physical hard copies -? might be the crucial adjustment needed to at last blow open the digital book market. It seemed like a no-brainer to me that Amazon was charging way too much for its e-books (not to mention the Kindle itself). But upon closer inspection, it clearly doesn’t add up that way. Tim O’Reilly explains why:

…the idea that there’s sufficient unmet demand to justify radical price cuts is totally wrongheaded. Unlike music, which is quickly consumed (a song takes 3 to 4 minutes to listen to, and price elasticity does have an impact on whether you try a new song or listen to an old one again), many types of books require a substantial time commitment, and having more books available more cheaply doesn’t mean any more books read. Regular readers already often have huge piles of unread books, as we end up buying more than we have time for. Time, not price, is the limiting factor.

Even assuming the rosiest of scenarios, Kindle readers are going to be a subset of an already limited audience for books. Unless some hitherto untapped reader demographic comes out of the woodwork, gets excited about e-books, buys Kindles, and then significantly surpasses the average human capacity for book consumption, I fail to see how enough books could be sold to recoup costs and still keep prices low. And without lower prices, I don’t see a huge number of people going the Kindle route in the first place. And there’s the rub.

Even if you were to go as far as selling books like songs on iTunes at 99 cents a pop, it seems highly unlikely that people would be induced to buy a significantly greater number of books than they already are. There’s only so much a person can read. The iPod solved a problem for music listeners: carrying around all that music to play on your Disc or Walkman was a major pain. So a hard drive with earphones made a great deal of sense. It shouldn’t be assumed that readers have the same problem (spine-crushing textbook-stuffed backpacks notwithstanding). Do we really need an iPod for books?

UPDATE: Through subsequent discussion both here and off the blog, I’ve since come around 360 back to my original hunch. See comment.

We might, maybe (putting aside for the moment objections to the ultra-proprietary nature of the Kindle), if Amazon were to abandon the per copy idea altogether and go for a subscription model. (I’m just thinking out loud here -? tell me how you’d adjust this.) Let’s say 40 bucks a month for full online access to the entire Amazon digital library, along with every major newspaper, magazine and blog. You’d have the basic cable option: all books accessible and searchable in full, as well as popular feedback functions like reviews and Listmania. If you want to mark a book up, share notes with other readers, clip quotes, save an offline copy, you could go “premium” for a buck or two per title (not unlike the current Upgrade option, although cheaper). Certain blockbuster titles or fancy multimedia pieces (once the Kindle’s screen improves) might be premium access only -? like HBO or Showtime. Amazon could market other services such as book groups, networked classroom editions, book disaggregation for custom assembled print-on-demand editions or course packs.

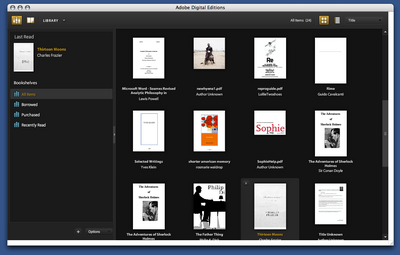

This approach reconceives books as services, or channels, rather than as objects. The Kindle would be a gateway into a vast library that you can roam about freely, with access not only to books but to all the useful contextual material contributed by readers. Piracy isn’t a problem since the system is totally locked down and you can only access it on a Kindle through Amazon’s Whispernet. Revenues could be shared with publishers proportionately to traffic on individual titles. DRM and all the other insults that go hand in hand with trying to manage digital media like physical objects simply melt away.

* * * * *

On a related note, Nick Carr talks about how the Kindle, despite its many flaws, suggests a post-Web2.0 paradigm for hardware:

If the Kindle is flawed as a window onto literature, it offers a pretty clear view onto the future of appliances. It shows that we’re rapidly approaching the time when centrally stored and managed software and data are seamlessly integrated into consumer appliances – all sorts of appliances.

The problem with “Web 2.0,” as a concept, is that it constrains innovation by perpetuating the assumption that the web is accessed through computing devices, whether PCs or smartphones or game consoles. As broadband, storage, and computing get ever cheaper, that assumption will be rendered obsolete. The internet won’t be so much a destination as a feature, incorporated into all sorts of different goods in all sorts of different ways. The next great wave in internet innovation, in other words, won’t be about creating sites on the World Wide Web; it will be about figuring out creative ways to deploy the capabilities of the World Wide Computer through both traditional and new physical products, with, from the user’s point of view, “no computer or special software required.”

That the Kindle even suggests these ideas signals a major advance over its competitors -? the doomed Sony Reader and the parade of failed devices that came before. What Amazon ought to be shooting for, however, (and almost is) is not an iPod for reading -? a digital knapsack stuffed with individual e-books -? but rather an interface to a networked library.