Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

I played a few rounds but quickly grew tired of the bland consensus that the game encourages. Matches tend to be banal, basic descriptors, while anything tricky usually results in a pass. In other words, all the pleasure of folksonomies — splicing one’s own idiosyncratic sense of things with the usually staid task of classification — is removed here. I don’t see why they don’t open the database up to much broader tagging. Integrate it with the image search and harvest a bigger crop of metadata.

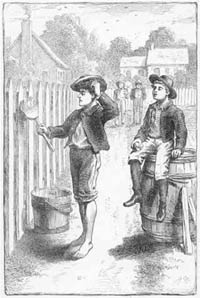

Right now, it’s more like Tom Sawyer tricking the other boys into whitewashing the fence. Only, I don’t think many will fall for this one because there’s no real incentive to participation beyond a halfhearted points system. For every matched tag, you and your partner score points, which accumulate in your Google account the more you play. As far as I can tell, though, points don’t actually earn you anything apart from a shot at ranking in the top five labelers, which Google lists at the end of each game. Whitewash, anyone?

In some ways, this reminded me of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an “artificial artificial intelligence” service where anyone can take a stab at various HIT’s (human intelligence tasks) that other users have posted. Tasks include anything from checking business hours on restaurant web sites against info in an online directory, to transcribing podcasts (there are a lot of these). “Typically these tasks are extraordinarily difficult for computers, but simple for humans to answer,” the site explains. In contrast to the Google image game, with the Mechanical Turk, you can actually get paid. Fees per HIT range from a single penny to several dollars.

I’m curious to see whether Google goes further with tagging. Flickr has fostered the creation of a sprawling user-generated taxonomy for its millions of images, but the incentives to tagging there are strong and inextricably tied to users’ personal investment in the production and sharing of images, and the building of community. Amazon, for its part, throws money into the mix, which (however modest the sums at stake) makes Mechanical Turk an intriguing, and possibly entertaining, business experiment, not to mention a place to make a few extra bucks. Google’s experiment offers neither, so it’s not clear to me why people should invest.

Category Archives: database

the database of intentions

Interesting edition of Open Source last week on “Google Sociology” with David Weinberger and John Battelle, author of the just-published “The Search: How Google and Its Rivals Rewrote the Rules of Business and Transformed Our Culture”. Listen here.

Weinberger has some interesting things to say about Google (and the other search engines) as “publishers.” I have some thoughts on that too. More to come later.

Battelle has done a great deal of thinking on search from a variety of angles: the technology of search, the economics of search, and the more esoteric dimensions of a “search” culture. He touches briefly on this last point, laying out a construct that is probably treated more extensively in his book: the “database of intentions.” By this he means the archive, or “artifact,” of the world’s search queries. A picture of the collective consciousness formed by the questions everyone is asking. Even now, when logged in to Google, a history of all your search query strings is kept – your own database of intentions. The potential value of this database is still being determined, but obvious uses are targeted advertising, and more relevant search results based on analysis of search histories.

As regards the collective database of intentions, Battelle speculates that future advances in artificial intelligence will likely draw on this enormous crop of information about how humans think and seek.