Last week I posted about Le mie elezioni, a film about the recent Italian elections constructed from footage shot by the general public, mostly part of Italy’s videoblogging community. Le mie elezioni will be released on the 15th of May: according to an article in Il manifesto more than 150 videobloggers have submitted more than 50 hours of materials which are being furiously edited right now. You can watch a rough cut of the trailer here.

The footage is being put together into an hour-long film by the website Nessuno.TV a portal for Italian videobloggers, which is run by Bruno Pellegrini, who also teaches the sociology of communications at the Universitá di Architettura in Rome. I sent him an email asking about the project; while Bruno happened to be in the U.S. last week, but his (and our) travel schedule didn’t allow him to stop by the Institute. Nonetheless, we conducted an interview, via email. My questions are in bold; his responses are indented.

The footage is being put together into an hour-long film by the website Nessuno.TV a portal for Italian videobloggers, which is run by Bruno Pellegrini, who also teaches the sociology of communications at the Universitá di Architettura in Rome. I sent him an email asking about the project; while Bruno happened to be in the U.S. last week, but his (and our) travel schedule didn’t allow him to stop by the Institute. Nonetheless, we conducted an interview, via email. My questions are in bold; his responses are indented.

Can you describe how the project came about?

It was born in a very natural way, as some of the vloggers who already participated at BlogTV (the first ever TV station broadcasting user-generated content) suggested covering the election together. Then the idea of the movie came up.

Is this project part of a larger Italian web response to media consolidation? How widely do people share your belief that the perception that big media has failed to cover things it should be covering?

I do not think this project is specific to Italy. Although the situation in my country is embarrassing I believe it is only a little ahead compared to what is going on abroad. Big media has failed (sometimes deliberately) to cover things all over the world for the last decades and the web has given people a chance to re-balance the power. Whereever and whenever there are major needs for a democracy, you can be sure something is going to happen . . . With regards to people, only a small part is conscious about what is going on, and the others are not helped by mass information . . . In general there is a common sense of distrust of politics, media and power.

In the U.S., the 2004 elections brought out – for the first time – a huge number of political bloggers; this seemed to be the first time that the blogosphere registered in the mainstream media, and there’s the perception that the U.S. blogosphere exploded at that point. Have these elections done the same thing in Italy? Or did people turn to the Internet earlier?

Not at all, unfortunately. The Italian blogosphere is not as mature as it is in the U.S. We still lack a common identity and, most of all, consciousness of the power of being media . . . Hopefully this will happen in the next political campaign, and I suspect it will come out not from the classic political separation (left and right) but from an increasing fight between young and old people with the latter trying to keep their undeserved priviledges . . .

How big is the videoblogging community in Italy? We periodically look in on it in the U.S., and while everyone loves Rocketboom, it doesn’t really seem to have taken off here as much as everyone expected (although maybe things like YouTube and Google Video are changing that). Did you find people getting interested in videoblogging because of the project, or was there already a vibrant community?

Vibrant is not exactly the right word, maybe promising would be more appropriate. I think it is a matter of critical mass and once reached it will grow exponentially like all the network related trends.

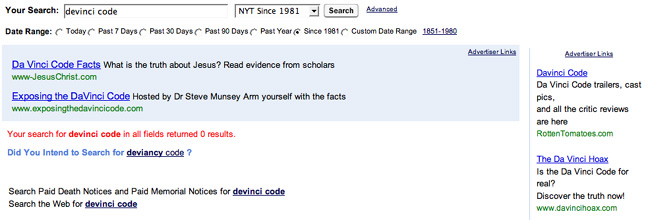

The question of copyright. Watching the clips, I couldn’t help but notice the music – songs by the Arctic Monkeys & Caparezza playing in the background, as well as video clips from the news and I think a couple of press photographs. In the U.S. documentary film makers increasingly have problems with clearance issues – the owners of the songs charge thousands of dollars for the rights to use even a few seconds of them. We’ve been covering this issue of fair use rather closely because it seems to figure in many of the things you can do with multimedia. I’m curious how much of a problem it is in Italy – is this something you worry about there?

So far it is not a problem at all and we can deal with the fair use regulation. I believe the majors will play harder in the future, especially with music and movies, but there are already good open access libraries and the Creative Commons movement is getting stronger in Italy too.

Many thanks to Bruno Pellegrini for being so generous with his time. If people have more questions about this project, don’t hesitate to leave them in the comments section.

An

An  The raw materials are

The raw materials are  It’s immediately apparent that most of these films are for the left. This isn’t an isolated occurance: the Italian left seems to have understood that the network can be a political force. In January, I

It’s immediately apparent that most of these films are for the left. This isn’t an isolated occurance: the Italian left seems to have understood that the network can be a political force. In January, I