every once in a while we see something that quickens the pulse. Jefferson Han, a researcher at NYU’s Computer Science Dept. has made a video showing a system which allows someone to manipulate objects in real time using all the fingers of both hands. watch the video and get a sense of what it will be like to be able to manipulate data in two and someday three dimensions by using intuitive body gestures.

Category Archives: computers

i want to be a machine

In 1963, long before computers became part of our consciousness, before Kasparov lost to Deep Blue, before HAL took over the spaceship, Andy Warhol said, “I want to be a machine.” Andy knew that machines were things to be feared, worshiped, admired and, therefore, emulated. His artwork was about people and ideas that were, more or less, generated by the machine: the media machine, the political machine, the printing press and the television, all cranking out iconic images that were powerful, not because they were complex, nuanced, interesting or even beautiful, but because they were relentless. Warhol’s brilliance was in recognizing how deep the machine metaphor had embedded itself into our personal ambitions and our collective self-image.

In 1963, long before computers became part of our consciousness, before Kasparov lost to Deep Blue, before HAL took over the spaceship, Andy Warhol said, “I want to be a machine.” Andy knew that machines were things to be feared, worshiped, admired and, therefore, emulated. His artwork was about people and ideas that were, more or less, generated by the machine: the media machine, the political machine, the printing press and the television, all cranking out iconic images that were powerful, not because they were complex, nuanced, interesting or even beautiful, but because they were relentless. Warhol’s brilliance was in recognizing how deep the machine metaphor had embedded itself into our personal ambitions and our collective self-image.

Fantasies about being machine-like, however, are not unique to the quirky imaginations of artists. Warhol would have been in good company with cognitive scientists who, for many years, have theorized that our brain works like a computer. This theory/myth is currently being debunked by a new Cornell study.

The theory that the mind works like a computer, in a series of distinct stages, was an important steppingstone in cognitive science, but it has outlived its usefulness, concludes a new Cornell University study. Instead, the mind should be thought of more as working the way biological organisms do: as a dynamic continuum, cascading through shades of grey.

Our mind works like a biological organism? Complex, untamed, “cascading through shades of grey,” oh my. Does that mean there are no definitive answers, only networks of possibility, spectrums of grey? If Andy were around today, he might have something to say about this revelatory denial of black and white thinking in an age of increasing fundementalism and exponential growth in media outlets. But we can only imagine the artwork he would have made.

the selected, annotated outbox of dave eggers

Email killed the practice of letter-writing so suddenly that we haven’t a chance to think about the consequences. The Times Book Review ran an essay this weekend on the problem this poses for literary historians, biographers and archivists, who long have relied on collected letters and papers to fill in the gaps between a writer’s published work. In the same review, the Times covers a new biography of the legendary critic Edmund Wilson largely based on his correspondences, and last week covered a new collection of the letters of poet James Wright. Letters are often treated as literature in themselves.

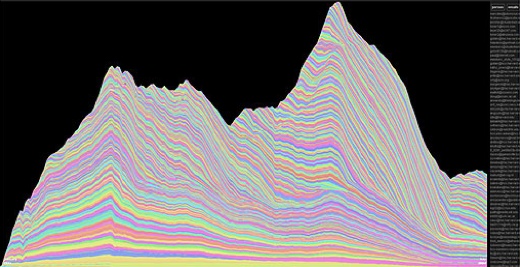

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

There isn’t necessarily anything less rich about email correspondence. It excels at capturing a vibrant volley of words with great immediacy, whereas paper letters permit deeper communiques, fewer and father between. But in some cases, these characterizations do not hold up. With reliable postal service, letters can fly back and forth quite rapidly. And just because an email suddenly appears in your box does not mean that it will be immediately read, let alone replied to. Sometimes we write long email letters, expecting that the receiver is busy and will take time to reply. These differences, true and false, are worth evaluating.

But if collected emails are to become a literary tool, there is no question that we will need more reliable ways of archiving and preserving digital correspondence. We will also need new editorial approaches for collecting and publishing them. A printed volume, or series of volumes, might be insufficient for presenting a massive 4 gigabyte email archive by Dave Eggers (No one wants to read the phone book from cover to cover). And according to the Times piece, Eggers’ agent Andrew Wylie is mulling over such a project. What would make more sense is an electronic edition that is essentially a selected or complete annotated Eggers Outbox, with folders and tags provided for categorization, a powerful search function, and the ability to organize according to your own interests. There would also be browsing and skimming tools that would allow a reader to move rapidly across vast tracts of correspondence and still find what they are looking for. And maybe, a way to email the author yourself and become a part of the living archive.