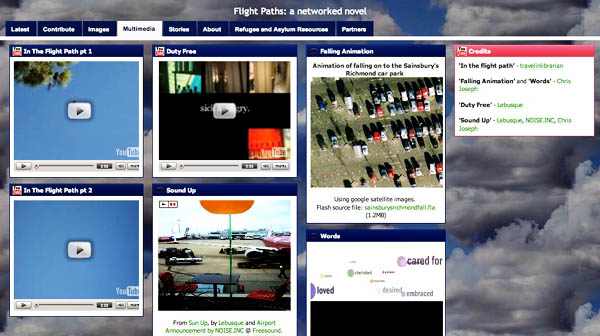

Back in December we announced the launch of Flight Paths, a “networked novel” that is currently being written by Kate Pullinger and Chris Joseph with feedback and contributions from readers. At that point, the Web presence for the project was a simple CommentPress blog where readers could post stories, images, multimedia and links, and weigh in on the drafting of terms and conditions for participation. Since then, Kate and Chris have been working on setting up a more flexible curatorial environment, and just this week they unveiled a lovely new Flight Paths site made in Netvibes.

Netvibes is a web-based application (still in beta) that allows you to build personalized start pages composed of widgets and modules which funnel in content from various data sources around the net (think My Yahoo! or iGoogle but with much more ability to customize). This is a great tool to try out for a project that is being composed partly out of threads and media fragments from around the Web. The blog is still embedded as a central element, and is still the primary place for reader-collaborators to contribute, but there are now several new galleries where reader-submitted works can be featured and explored. It’s a great new platform and an inventive solution to one of CommentPress’s present problems: that it’s good at gathering content but not terribly good at presenting it. Take a look, and please participate if you feel inspired.

Multimedia gallery on the new Flight Paths site

Category Archives: commentpress

developing books in networked communities: a conversation with don waters

Two weeks ago, when the blog-based peer review of Noah Wardrip-Fruin’s Expressive Processing began on Grand Text Auto, Bob sent a note about the project to Don Waters, the program officer for scholarly communications at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation -? someone very much at the forefront of developments in the digital publishing arena. He wrote back intrigued but slightly puzzled as to the goals, scope and definitions of the experiment. We forwarded the note to Noah and to Doug Sery, Noah’s editor at MIT Press, and decided each to write some clarifying responses from our different perspectives: book author/blogger (Noah), book editor (Doug), and web editor (myself). The result is an interesting exchange about networked publishing and useful meta-document about the project. As our various responses, and Don’s subsequent reply, help to articulate, playing with new forms of peer review is only one aspect of this experiment, and maybe not even the most interesting one. The exchange is reproduced below (a couple of names mentioned have been made anonymous).

Don Waters (Mellon Foundation):

Thanks, Bob. This is a very interesting idea. In reading through the materials, however, I did not really understand how, if at all, this “experiment” would affect MIT Press behavior. What are the hypotheses being tested in that regard? I can see, from one perspective, that this “experiment” would result purely in more work for everyone. The author would get the benefit of the “crowd” commenting on his work, and revise accordingly, and then the Press would still send the final product out for peer review and copy editing prior to final publication.

Don

Ben Vershbow (Institute for the Future of the Book):

There are a number of things we set out to learn here. First, can an open, Web-based review process make a book better? Given the inherently inter-disciplinary nature of Noah’s book, and the diversity of the Grand Text Auto readership, it seems fairly likely that exposing the manuscript to a broader range of critical first-responders will bring new things to light and help Noah to hone his argument. As can be seen in his recap of discussions around the first chapter, there have already been a number of incisive critiques that will almost certainly impact subsequent revisions.

Second, how can we use available web technologies to build community around a book, or to bring existing communities into a book’s orbit? “Books are social vectors, but publishers have been slow to see it,” writes Ursula K. Le Guin in a provocative essay in the latest issue of Harper’s. For the past three years, the Institute for the Future of the Book’s mission has been to push beyond the comfort zone of traditional publishers, exploring the potential of networked technologies to enlarge the social dimensions of books. By building a highly interactive Web component to a text, where the author and his closest peers are present and actively engaged, and where the entire text is accessible with mechanisms for feedback and discussion, we believe the book will occupy a more lively and relevant place in the intellectual ecology of the Internet and probably do better overall in the offline arena as well.

The print book may have some life left in it yet, but it now functions within a larger networked commons. To deny this could prove fatal for publishers in the long run. Print books today need dynamic windows into the Web and publishers need to start experimenting with the different forms those windows could take or else retreat further into marginality. Having direct contact with the author -? being part of the making of the book -? is a compelling prospect for the book’s core audience and their enthusiasm is likely to spread. Certainly, it’s too early to make a definitive assessment about the efficacy of this Web outreach strategy, but initial indicators are very positive. Looked at one way, it certainly does create more work for everyone, but this is work that has to be done. At the bare minimum, we are building marketing networks and generating general excitement about the book. Already, the book has received a great deal of attention around the blogosphere, not just because of its novelty as a publishing experiment, but out of genuine interest in the subject matter and author. I would say that this is effort well spent.

It’s important to note that, despite CHE’s lovely but slightly sensational coverage of this experiment as a kind of mortal combat between traditional blind peer review and the new blog-based approach, we view the two review processes as complementary, not competitive. At the end, we plan to compare the different sorts of feedback the two processes generate. Our instinct is that it will suggest hybrid models rather than a wholesale replacement of one system with another.

That being said, our instincts tell us that open blog-based review (or other related forms) will become increasingly common practice among the next generation of academic writers in the humanities. The question for publishers is how best to engage with, and ideally incorporate, these new practices. Already, we see a thriving culture of pre-publication peer review in the sciences, and major publishers such as Nature are beginning to build robust online community infrastructures so as to host these kinds of interactions within their own virtual walls. Humanities publishers should be thinking along the same lines, and partnerships with respected blogging communities like GTxA are a good way to start experimenting. In a way, the MIT-GTxA collab represents an interface not just of two ideas of peer review but between two kinds of publishing imprints. Both have built a trusted name and become known for a particular editorial vision in their respective (and overlapping) communities. Each excels in a different sort of publishing, one print-based, the other online community-based. Together they are greater than the sum of their parts and suggest a new idea of publishing that treats books as extended processes rather than products. MIT may regard this as an interesting but not terribly significant side project for now, but it could end up having a greater impact on the press (and hopefully on other presses) than they expect.

All the best,

Ben

Noah Wardrip-Fruin (author, UC San Diego):

Hi Bob –

Yesterday I went to meet some people at a game company. There’s a lot of expertise there – and actually quite a bit of reflection on what they’re doing, how to think about it, and so on. But they don’t participate in academic peer review. They don’t even read academic books. But they do read blogs, and sometimes comment on them, and I was pleased to hear that there are some Grand Text Auto readers there.

If they comment on the Expressive Processing manuscript, it will create more work for me in one sense. I’ll have to think about what they say, perhaps respond, and perhaps have to revise my text. But, from my perspective, this work is far outweighed by the potential benefits: making a better book, deepening my thinking, and broadening the group that feels academic writing and publishing is potentially relevant to them.

What makes this an experiment, from my point of view, is the opportunity to also compare what I learn from the blog-based peer review to what I learn from the traditional peer review. However, this will only be one data point. We’ll need to do a number of these, all using blogs that are already read by the audience we hope will participate in the peer review. When we have enough data points perhaps we’ll start to be able to answer some interesting questions. For example, is this form of review more useful in some cases than others? Is the feedback from the two types of review generally overlapping or divergent? Hopefully we’ll learn some lessons that presses like MITP can put into practice – suggesting blog-based review when it is most appropriate, for example. With those lessons learned, it will be time to design the next experiment.

Best,

Noah

Doug Sery (MIT Press):

Hi Bob,

I know Don’s work in digital libraries and preservation, so I’m not surprised at the questions. While I don’t know the breadth of the discussions Noah and Ben had around this project, I do know that Noah and I approached this in a very casual manner. Noah has expressed his interest in “open communication” any number of times and when he mentioned that he’d like to “crowd-source” “Expressive Processing” on Grand Text Auto I agreed to it with little hesitation, so I’m not sure I’d call it an experiment. There are no metrics in place to determine whether this will affect sales or produce a better book. I don’t see this affecting the way The MIT Press will approach his book or publishing in general, at least for the time being.

This is not competing with the traditional academic press peer-review, although the CHE article would lead the reader to believe otherwise (Jeff obviously knows how to generate interest in a topic, which is fine, but even a games studies scholar, in a conversation I had with him today, laughingly called the headline “tabloidesque.”) . While Noah is posting chapters on his blog, I’m having the first draft peer-reviewed. After the peer-reviews come in, Noah and I will sit down to discuss them to see if any revisions to the manuscript need to be made. I don’t plan on going over the GTxA comments with Noah, unless I happen to see something that piques my interest, so I don’t see any additional work having to be done on the part of MITP. It’s a nice way for Noah to engage with the potential audience for his ideas, which I think is his primary goal for all of this. So, I’m thinking of this more as an exercise to see what kind of interest people have in these new tools and/or mechanisms. Hopefully, it will be a learning experience that MITP can use as we explore new models of publishing.

Hope this helps and that all’s well.

Best,

Doug

Don Waters:

Thanks, Bob (and friends) for this helpful and informative feedback.

As I understand the explanations, there is a sense in which the experiment is not aimed at “peer review” at all in the sense that peer review assesses the qualities of a work to help the publisher determine whether or not to publish it. What the exposure of the work-in-progress to the community does, besides the extremely useful community-building activity, is provide a mechanism for a function that is now all but lost in scholarly publishing, namely “developmental editing.” It is a side benefit of current peer review practice that an author gets some feedback on the work that might improve it, but what really helps an author is close, careful reading by friends who offer substantive criticism and editorial comments. Most accomplished authors seek out such feedback in a variety of informal ways, such as sending out manuscripts in various stages of completion to their colleagues and friends. The software that facilitates annotation and the use of the network, as demonstrated in this experiment, promise to extend this informal practice to authors more generally. I may have the distinction between peer review and developmental editing wrong, or you all may view the distinction as mere quibbling, but I think it helps explain why CHE got it so wrong in reporting the experiment as struggle between peer review and the blog-based approach. Two very different functions are being served, and as you all point out, these are complementary rather than competing functions.

I am very intrigued by the suggestions that scholarly presses need to engage in this approach more generally, and am eagerly learning from this and related experiments, such as those at Nature and elsewhere, more about the potential benefits of this kind of approach.

Great work and many thanks for the wonderful (and kind) responses.

Best,

Don

expressive processing: an experiment in blog-based peer review

An exciting new experiment begins today, one which ties together many of the threads begun in our earlier “networked book” projects, from Without Gods to Gamer Theory to CommentPress. It involves a community, a manuscript, and an open peer review process -? and, very significantly, the blessing of a leading academic press. (The Chronicle of Higher Education also reports.)

The community in question is Grand Text Auto, a popular multi-author blog about all things relating to digital narrative, games and new media, which for many readers here, probably needs no further introduction. The author, Noah Wardrip-Fruin, a professor of communication at UC San Diego, a writer/maker of digital fictions, and, of course, a blogger at GTxA. His book, which starting today will be posted in small chunks, open to reader feedback, every weekday over a ten-week period, is called Expressive Processing: Digital Fictions, Computer Games, and Software Studies. It probes the fundamental nature of digital media, looking specifically at the technical aspects of creation -? the machines and software we use, the systems and processes we must learn end employ in order to make media -? and how this changes how and what we create. It’s an appropriate guinea pig, when you think about it, for an open review experiment that implicitly asks, how does this new technology (and the new social arrangements it makes possible) change how a book is made?

The community in question is Grand Text Auto, a popular multi-author blog about all things relating to digital narrative, games and new media, which for many readers here, probably needs no further introduction. The author, Noah Wardrip-Fruin, a professor of communication at UC San Diego, a writer/maker of digital fictions, and, of course, a blogger at GTxA. His book, which starting today will be posted in small chunks, open to reader feedback, every weekday over a ten-week period, is called Expressive Processing: Digital Fictions, Computer Games, and Software Studies. It probes the fundamental nature of digital media, looking specifically at the technical aspects of creation -? the machines and software we use, the systems and processes we must learn end employ in order to make media -? and how this changes how and what we create. It’s an appropriate guinea pig, when you think about it, for an open review experiment that implicitly asks, how does this new technology (and the new social arrangements it makes possible) change how a book is made?

The press that has given the green light to all of this is none other than MIT, with whom Noah has published several important, vibrantly inter-disciplinary anthologies of new media writing. Expressive Processing his first solo-authored work with the press, will come out some time next year but now is the time when the manuscript gets sent out for review by a small group of handpicked academic peers. Doug Sery, the editor at MIT, asked Noah who would be the ideal readers for this book. To Noah, the answer was obvious: the Grand Text Auto community, which encompasses not only many of Noah’s leading peers in the new media field, but also a slew of non-academic experts -? writers, digital media makers, artists, gamers, game designers etc. -? who provide crucial alternative perspectives and valuable hands-on knowledge that can’t be gotten through more formal channels. Noah:

Blogging has already changed how I work as a scholar and creator of digital media. Reading blogs started out as a way to keep up with the field between conferences — and I soon realized that blogs also contain raw research, early results, and other useful information that never gets presented at conferences. But, of course, that’s just the beginning. We founded Grand Text Auto, in 2003, for an even more important reason: blogs can create community. And the communities around blogs can be much more open and welcoming than those at conferences and festivals, drawing in people from industry, universities, the arts, and the general public. Interdisciplinary conversations happen on blogs that are more diverse and sustained than any I’ve seen in person.

Given that ours is a field in which major expertise is located outside the academy (like many other fields, from 1950s cinema to Civil War history) the Grand Text Auto community has been invaluable for my work. In fact, while writing the manuscript for Expressive Processing I found myself regularly citing blog posts and comments, both from Grand Text Auto and elsewhere….I immediately realized that the peer review I most wanted was from the community around Grand Text Auto.

Sery was enthusiastic about the idea (although he insisted that the traditional blind review process proceed alongside it) and so Noah contacted me about working together to adapt CommentPress to the task at hand.

The challenge technically was to integrate CommentPress into an existing blog template, applying its functionality selectively -? in other words, to make it work for a specific group of posts rather than for all content in the site. We could have made a standalone web site dedicated to the book, but the idea was to literally weave sections of the manuscript into the daily traffic of the blog. From the beginning, Noah was very clear that this was the way it needed to work, insisting that the social and technical integration of the review process were inseparable. I’ve since come to appreciate how crucial this choice was for making a larger point about the value of blog-based communities in scholarly production, and moreover how elegantly it chimes with the central notions of Noah’s book: that form and content, process and output, can never truly be separated.

The challenge technically was to integrate CommentPress into an existing blog template, applying its functionality selectively -? in other words, to make it work for a specific group of posts rather than for all content in the site. We could have made a standalone web site dedicated to the book, but the idea was to literally weave sections of the manuscript into the daily traffic of the blog. From the beginning, Noah was very clear that this was the way it needed to work, insisting that the social and technical integration of the review process were inseparable. I’ve since come to appreciate how crucial this choice was for making a larger point about the value of blog-based communities in scholarly production, and moreover how elegantly it chimes with the central notions of Noah’s book: that form and content, process and output, can never truly be separated.

Up to this point, CommentPress has been an all or nothing deal. You can either have a whole site working with paragraph-level commenting, or not at all. In the technical terms of WordPress, its platform, CommentPress is a theme: a template for restructuring an entire blog to work with the CommentPress interface. What we’ve done -? with the help of a talented WordPress developer named Mark Edwards, and invaluable guidance and insight from Jeremy Douglass of the Software Studies project at UC San Diego (and the Writer Response Theory blog) -? is made CommentPress into a plugin: a program that enables a specific function on demand within a larger program or site. This is an important step for CommentPress, giving it a new flexibility that it has sorely lacked and acknowledging that it is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

Just to be clear, these changes are not yet packaged into the general CommentPress codebase, although they will be before too long. A good test run is still needed to refine the new model, and important decisions have to be made about the overall direction of CommentPress: whether from here it definitively becomes a plugin, or perhaps forks into two paths (theme and plugin), or somehow combines both options within a single package. If you have opinions on this matter, we’re all ears…

But the potential impact of this project goes well beyond the technical.

It represents a bold step by a scholarly press -? one of the most distinguished and most innovative in the world -? toward developing new procedures for vetting material and assuring excellence, and more specifically, toward meaningful collaboration with existing online scholarly communities to develop and promote new scholarship.

It seems to me that the presses that will survive the present upheaval will be those that learn to productively interact with grassroots publishing communities in the wild of the Web and to adopt the forms and methods they generate. I don’t think this will be a simple story of the blogosphere and other emerging media ecologies overthrowing the old order. Some of the older order will die off to be sure, but other parts of it will adapt and combine with the new in interesting ways. What’s particularly compelling about this present experiment is that it has the potential to be (perhaps now or perhaps only in retrospect, further down the line) one of these important hybrid moments -? a genuine, if slightly tentative, interface between two publishing cultures.

Whether the MIT folks realize it or not (their attitude at the outset seems to be respectful but skeptical), this small experiment may contain the seeds of larger shifts that will redefine their trade. The most obvious changes leveled on publishing by the Internet, and the ones that get by far the most attention, are in the area of distribution and economic models. The net flattens distribution, making everyone a publisher, and radically undercuts the heretofore profitable construct of copyright and the whole system of information commodities. The effects are less clear, however, in those hardest to pin down yet most essential areas of publishing -? the territory of editorial instinct, reputation, identity, trust, taste, community… These are things that the best print publishers still do quite well, even as their accounting departments and managing directors descend into panic about the great digital undoing. And these are things that bloggers and bookmarkers and other web curators, archivists and filterers are also learning to do well -? to sift through the information deluge, to chart a path of quality and relevance through the incredible, unprecedented din.

This is the part of publishing that is most important, that transcends technological upheaval -? you might say the human part. And there is great potential for productive alliances between print publishers and editors and the digital upstarts. By delegating half of the review process to an existing blog-based peer community, effectively plugging a node of his press into the Web-based communications circuit, Doug Sery is trying out a new kind of editorial relationship and exercising a new kind of editorial choice. Over time, we may see MIT evolve to take on some of the functions that blog communities currently serve, to start providing technical and social infrastructure for authors and scholarly collectives, and to play the valuable (and time-consuming) roles of facilitator, moderator and curator within these vast overlapping conversations. Fostering, organizing, designing those conversations may well become the main work of publishing and of editors.

I could go on, but better to hold off on further speculation and to just watch how it unfolds. The Expressive Processing peer review experiment begins today (the first actual manuscript section is here) and will run for approximately ten weeks and 100 thousand words on Grand Text Auto, with a new post every weekday during that period. At the end, comments will be sorted, selected and incorporated and the whole thing bundled together into some sort of package for MIT. We’re still figuring out how that part will work. Please go over and take a look and if a thought is provoked, join the discussion.

new commentpress version available: plays well with latest wordpress!

We’ve finally squashed the bug that made CommentPress incompatible with the latest version of WordPress (2.3), so anyone out there with a CP installation can finally go ahead and upgrade:

CommentPress 1.4.1 »

Other than the compatibility fix, 1.4.1 is exactly the same as 1.4. Of course, there are numerous improvements we’d still like to make, and plans for that are underway. Stay tuned.

Also: tomorrow I’m going to be announcing an exciting new CommentPress publishing experiment that will suggest possible future directions for the tool’s development.

anatomy of a debate

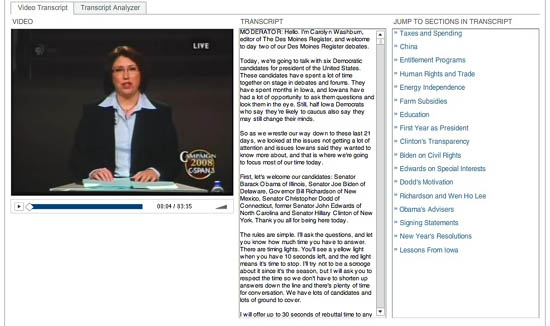

The New York Times continues to do quality interactive work online. Take a look at this recent feature that allows you to delve through video and transcript from the final Democratic presidential candidate debate in Iowa (Dec. 13, ’07). It begins with a lovely navigation tool that allows you to jump through the video topic by topic. Clicking text in the transcript (center column) or a topic from the list (right column) jumps you directly to the corresponding place in the video.

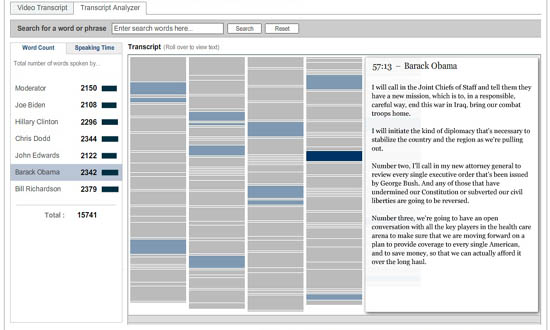

The second part is a “transcript analyzer,” which gives a visual overview of the debate. The text is laid out in miniature in a simple, clean schematic, navigable by speaker. Click a name in the left column and the speaker’s remarks are highlighted on the schematic. Hover over any block of text and that detail of the transcript pops up for you to read. You can also search the debate by keyword and see word counts and speaking times for each candidate.

These are fantastic tools -? if only they were more widely available. These would be amazing extensions to CommentPress.

using commentpress with adolescents, first assessment (sol gaitan)

The bulk of this post is from Sol Gaitan, a teacher of Spanish language and literature at the Dalton School in New York and an occasional writer on this blog. Over the past couple of months Sol has been using CommentPress in an assignment for one of her classes and recently took the time to reflect on how the experiment has gone. The result is a fascinating report from the front lines on the complexities and ambiguities of employing digital technologies in the classroom. From this one trial it becomes obvious that the digital divide can run through almost any place – ?even a hyper-privileged school like Dalton in the Upper East Side of Manhattan – ?and that maintaining a communal Web environment as an annex to the classroom presents tremendous benefits as well as tremendous burdens.

I am using CommentPress in my Hispanic Literature class to study Gabriel García Márquez. Instead of putting his work in to CommentPress, I decided to put in my introduction and the goals for this part of the course, what at Dalton we call “the Assignment” -? one of our pedagogical pillars. I instructed my students to comment on the assignment based on what they learned after reading his collection of short stories, Los funerales de la Mamá Grande. I also added a section of guiding questions, a section with excerpts from one of the short stories, and a few other texts. My expectation was that the students would comment on my text, but they went to the specific questions and commented there. I believe they felt more comfortable with a familiar format. We still need to read his novel El coronel no tiene quien le escriba so I have asked the class to enter comments to my introductory text as the culmination of this assignment. My rationale behind all of this is that students fully grasp what I tell them when I present an author only after they have read his/her works and not the other way around. Furthermore, CommentPress allows me to evaluate their work within the context of their whole experience as they gain knowledge and understanding along the way, something that a final paper doesn’t necessarily do. I also value enormously the fact that the classroom extends beyond its physical confines.

After about one month of using CommentPress, I decided to have my students assess their experience with this medium for communication outside the classroom. All students appreciated the advantages of sharing their literary thoughts in a forum that provides the immediacy of classroom discussions, but also allows them the time to elaborate their thoughts before expressing them. This is especially important in a class conducted entirely in a foreign language.

At an institution like Dalton where computers are an integral part of daily communications, it took me by surprise to realize that there is still a digital divide. One half of my class is comprised of affluent Manhattan kids and the other half of less privileged ones. Interestingly, the latter expressed some level of discomfort in dealing with technology. The rest, who also happen to be younger, were absolutely excited about it. For the less privileged ones, lack of fast Internet connections at home or older, slower computers are major obstacles to the use of a networked assignment. Also some complained that they cannot read/work on this assignment on the subway. This has to do with the fact that these students have long commutes while the more well to do students often live “around the corner” from the school. One student claimed that he doesn’t have four computers at home as some of his classmates do. This presents a logistical problem since some students may use this as an excuse for not posting as often as they should. Regardless, inequality is definitely an issue.

I realized that the need to post comments regularly helps students to know where they stand regarding grades because I use their posts in lieu of in-class essays and papers. This opens up the evaluation process as students are in intimate contact not only with their individual progress and production, but also with that of the whole class.

Group discussion is central to Dalton’s philosophy thanks to our small classes. Thus, students do not necessarily value conversation beyond the classroom as much as students in schools with larger classes might do. One student argued that she had already shared her thoughts in class and preferred working after school on papers in the privacy of her home. Others argued the opposite, that it’s a very useful thing to be reading at home and right then and there have the chance to share their ideas with their classmates and with me.

A frequent complaint from students who expressed uneasiness with networked assignments was that we are using their favorite tool for communication, the computer, for a school assignment. All agreed that e-mail, social networking and text messaging are their preferred ways to connect. Why is it then that they object to having this applied to their learning experience? They say they feel an academic blog demands a more “serious” approach and a certain degree of formality, and also seem annoyed at the fact that they MUST comment. We agreed that they could feel free to be less formal in their postings (though when I read them, I notice that they cannot avoid showing their intelligence and articulacy) and that they should enter a minimum of two comments per week. Also, because they are writing in Spanish, they must also enter grammatical corrections.

CommentPress has added work to my daily life because I must check student work more often, I must send them grammatical tidbits, and I must add my own comments when things need clarification. However, I can feel the pulse of the class more closely and accurately, and I don’t have a ton of papers or exams to grade all at once.

unbound reader

CommentPress, be it remembered, is a blog hack. A fairly robust one to be sure, and one which we expect to get significant near-term mileage out of, but still an adaptation of a relatively brittle publishing architecture. BookGlutton – ?a new community reading site that goes public beta next month – ?takes a shot at building social reading tools from scratch, and the first glimpses look promising. I’m still awaiting my beta tester account so it’s hard to say how well this actually works (and whether it’s Flash-based or Ajax-driven etc.), but a demo on their development blog walks through most of the social features of their browser-based “Unbound Reader.” They seem to have gotten a lot right, but I’m still curious to see how, if at all, they handle multimedia and interlinking between and within books. We’ll be watching this one closely…..Also, below the video, check out some explanatory material by BookGlutton’s creators, Aaron Miller and Travis Alber, that was forwarded to us the other day.

The first, the main BookGlutton website, is a catalog and community where users can upload work or select a piece of public domain writing, create reading groups and tag literature. The second part of the site – its centerpiece – is the Unbound Reader. It has a web-based format where users can read and discuss the book right inside the text. The Unbound Reader uses “proximity chat,” which allows users to discuss the book with other readers close to them in the text (thus focusing discussion, and, as an added benefit, keeping people from hearing about the end). It also has shared annotations, so people can leave a comment on any paragraph and other readers can respond. By encouraging users to talk in a context-specific way about what they’re reading, Bookglutton hopes to help those who want to talk about books (or original writing) with their friends (across cities, for example), students who want to discuss classic works (perhaps for a class), or writers who want to get feedback on their own pieces. Naturally, when the conversation becomes distracting, a user can close off the discussion without exiting the Reader.

Additionally, BookGlutton is working to facilitate adoption of on-line reading. Book design is an important aspect of the reader, and it incorporates design elements, like dynamic dropcaps. Moreover, the works presented in the catalog are standards-based (BookGlutton is an early adopter of the International Digital Publishing Forum’s .epub format for ebooks), and allows users to download a copy of anything they upload in this format for use elsewhere.

commentpress and the communications circuit

So much to say about this but for the moment I only have time for a quick link. Our close friend and colleague Kathleen Fitzpatrick just published a must-read paper on MediaCommons, in conjunction with the Journal of Electronic Publishing. The paper is about CommentPress, but it’s a lot more than that. It’s a deep look at how Internet-based technologies hold the potential for a large-scale shift in scholarly communication toward a more communal model, taking CommentPress as just a small intimation of things possibly to come. What’s particularly gratifying for this reader is how Kathleen puts CommentPress in the larger context from which it was developed-?in particular, the rise of blogs and the move in some wired circles of the academy back to something resembling the coffeehouse model of scholarly conversation.

Two years ago we held an informal meeting of leading academic bloggers to discuss how this new Web-based conversation perhaps contained the seeds of broader change in scholarly publishing. Out of the ideas that were thrown about in that meeting grew our series of blog hacks that we loosely termed “networked books,” which, in turn, eventually evolved into CommentPress (not to mention MediaCommons). Kathleen’s paper brilliantly draws it all together.

Of course, CommentPress represents only the tiniest step forward. But perhaps out of Kathleen’s elegant, lucid argument we can draw the idea for the next experiment. To that end, I urge everyone to spend time on the CommentPress version (always nice when form engages so directly with content) and to continue the conversation there.

p.s. -? also feel free to look at an earlier version of this paper, which Kathleen workshopped in CommentPress.

commentpress in the chronicle

There’s a nice article about CommentPress this week in the Chronicle of Higher Education. Unfortunately, it’s subscription only. Here’s the link for those of you with access. I’m working on getting permission to offer a full PDF.

UPDATE: The Chronicle has kindly furnished us with a PDF. Help yourself.

commentpress in the classroom 2

There are a couple of nice classroom implementations of CommentPress that I wanted to share, one that we set up by request, another done independently.

1. The first is an edition of Dante’s Inferno (Longfellow translation) for a literature seminar at the Pacific Northwest College of Art, “The Seven Deadly Sins,” taught by Trevor Dodge.

2. The second is “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” a seminal text in the history of computing by J.C.R. Licklider for a Harvard History of Science course, “Introduction to the History of Software and Networks”. This was brought to my attention by the teacher, Christopher Kelty, a professor of anthropology at Rice University, who is teaching this term at Harvard.

It’s still early in the semester but you can already see a substantial amount of discussion unfolding on both sites (be sure to use the “Browse Comments” navigation on the right sidebar to get a sense of where in the document discussion is happening, and who is participating). Kelty in particular encourages other knowledgeable readers from around the Web to make use of the Licklider text.