It’s mainly the literary world that assumes fictional work to be best when the creation of only one person. Most TV shows, movies, games and comics are created by teams. But though creativity here is not bound by the Romantic conception of the individual Artist, neither is it free for all. Fan fiction notwithstanding, as the property of publisher, broadcast company or studio, fictional universes are strictly controlled.

In the comics world, there are a handful of characters that could be described as explicitly ‘open-source’. Mythic characters are no-one’s property. Michael Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius was created with the intention that he be available for use as an open character. And Octobriana, a kind of socialist Barbarella, is Communist in both origin and legal status. Allegedly – though the story is somewhat murky – the creation of a 1960s Soviet underground group, her genesis outside Western comics publishing has meant that Octobriana has always existed in the public domain, and she has appeared in numerous different universes.

Inspired partly by Octobriana, in 2001 Barbelith founder and Web commentator Tom Coates and comic artist Steven Wintle led a community discussion about open-source narrative figures. As a result of these discussions, the group decided to create their own: in discussions over the next few months, Jenny Everywhere, aka ‘The Shifter’ was born.

Wintle’s original sketch for Jenny (Source: The Shifter Archive)

Jenny has certain core characteristics. She is a multidimensional person able to appear anywhere, in any universe, at any time. She can be in more than one place at a time. Her favorite food is toast, she wears goggles on her forehead, she is usually depicted with short dark hair and comfortable clothing. (The discussion threads where these characteristics were agreed make intriguing reading). But though she as some distinguishing features, she is explicitly available for any artist to use, providing the following text (first associated with Jenny in 2002) appears alongside:

The character of Jenny Everywhere is available for use by anyone, with only one condition. This paragraph must be included in any publication involving Jenny Everywhere, in order that others may use this property as they wish. All rights reversed.

I wasn’t part of Jenny’s genesis. I came across her only recently, while hunting for something else, and was fascinated. An explicitly open-source character: neither a proprietary figure repurposed on the fringes of legality by fan communities, nor a mythic and hence uncopyrightable figure, nor one whose copyright has simply lapsed, but a set of narrative opportunities co-created and available for everyone to use. As much a political gesture as an artistic framework. I wanted evidence that she’d grown beyond that initial idea.

A bit of Web archaeology turned up a cluster of excitement and creative activity between 2001 and 2003 centering on the Barbelith community. She made appearances in numerous webcomics, turned up on blogs, popped up on Boing Boing. But then it all went quiet again.

I’d had hopes that Jenny might be, as the NYT article suggested, a herald of cultures to come. And there’s nothing more dispiriting than to read past predictions for phenomena that never came to be. But websites become flavor of the month so swiftly, and fade just as swiftly: it seemed that Jenny Everywhere just a transient moment in the hyperaccelerated maelstrom of geek subcultures.

But it seems I was wrong. Jenny is making a comeback. A 2007 Jenny competition on Stripfight saw a rash of new appearances; around the same time The Shifter Archive was launched, a new attempt by US comic artist David ‘Fesworks’ Leyk (to whom I’m hugely indebted for the information in this article) to collate and make available all extant Jenny Everywhere work. And new comics are beginning to appear.

A common pattern of relatively self-organizing co-creation sees a notionally ‘flat’ structure in fact driven by a self-selecting ‘core’ that gives the whole collective focus and drives creative energy. When this core steps back, the entire project often falters. I’ve found myself speculating: did Jenny’s initial core creators find their open-source character, unprotected by the corporate interests of a publisher or distributor, mutating to a point where she ceased to interest them? Or was it just a case of people moving on to new projects?

Either way, it points to the fact that for an open-source idea to reproduce, it must be able to outgrow its pioneers. After the initial enthusiasm died down, Jenny is still going strong: not harbored and protected by a close group in the bosom of a web community, but at large and self-reproducing. As ‘Fesworks’ puts it:

“There is no “official” site for Jenny Everywhere. Since she is Public Domain, and open-source […], technically every single Jenny Everywhere comic and story out there is “Fan Fiction”. They only connect to other people’s stories and comic if they choose to connect them.”

Jenny is a tantalizing glimpse of how collaborative, open creativity can be accelerated by the Web. Compared to her print prototype Octobriana, her spread in just seven years is phenomenal. But she raises many questions. For one thing, it is hard to see how a character not possessing quantum superpowers could survive the narrative vicissitudes of starring in the creations of multiple writers without disintegrating to meaninglessness – which in turn may mean that Jenny is a one-off. Then, her genesis and (still short) history is an intriguing case study of the difficulties of balancing creative vision with open collaboration – a problem, arguably, that also faced the Million Penguins wiki-novel and is at the core of the complicated relationship between artists and the Web.

And finally, it’s also about archiving, the fragility of Web history and – Wayback Machine notwithstanding – the rapid decay of old digital artefacts. 2003 is not a long time ago, but many of the old Jenny links are broken. Without the efforts of ‘Fes’, Jenny might be little more than a memory by now. Does any of this matter? If the Web is to become a meaningful locus for creative work, then these are indeed questions to take seriously.

Category Archives: comics

networked comics

Last week in Columbus, OH, I saw Scott McCloud give a fantastic presentation about creativity and storytelling using sequential art. I got two books signed, and since I was the last person on line, I started a little conversation about networked comics.

First off, it’s not every day that you get to meet one of your idols. He’s influenced the way that I think about storytelling and sequential art, which manages to have everyday repercussions in my work in interaction design and wireframing. Understanding Comics is right at the top of my practical reading guide with the Polar Bear book and Visual Displays of Quantitative Information.

Secondly, in Reinventing Comcis he covers a lot of territory with regard to the form that web comics can take and the method by which they can support themselves. But, as he notes in his presentation, while he was focused on the new openness of a boundless screen, webcomics recapitulated traditional forms and appeared like toadstools after a spring rain. As he said, “Tens of thousands—literally, tens of thousands of webcomics are out there today.” They are easy to find, but they’re guided by the goals of traditional comics, and made with many of the same choices in framing and pacing, even if their story lines are wildly varied.

In a previous post I said “The next step for online comics is to enhance their networked and collaborative aspect while preserving the essential nature of comics as sequential art.” I still think there’s something there, so I posed that questiont to Scott. He politely redirected, saying the form of a networked comic is completely unknown and that the discussion would last for many hours. Offhand, he knew of only a few experiments. He did say, “The process will be more interesting than the final product.” This is something that we say here with regards to Wikipedia, but even more so with collaborative fiction as in 1mil Penguins. So without further guidance, I ventured into the web myself, searching for examples of what I would call networked comics.

One nascent form of collaborative art has been the (relatively) popular practice of putting up one half of the equation—the art only, or the words only—and getting someone else to do the other half. If you said that sounds like regular comix, you’d be right. It’s normal practice in the sequential art world to have a writer and an artist collaborate on a story. But the novelty here is having multiple writers work with the same panels, with an artist who doesn’t know what she is drawing for. Words, infinitely malleable, are shaped to fit the images, sometimes with implausible but funny results. Here’s an example that Kristopher Straub and Scott Kurtz have started on Halfpixel.com. They call it “Web You.0 (beta),” with the tagline “Infinite possible punchlines!” You take an image, put new words in the balloons, and resubmit the comic. The result: user-generated comics. Not necessarily good comics, but that’s not quite the point.

But that’s about it. There isn’t much in the way of a discussion going on about networked comics. This is understandable: making images is hard. Making images that are tied to a text is harder. This is the art and science of comics, and it’s difficult to see how they can be pried apart to create room for growth without completely disrupting the narrative structures inherent to the medium. When I look for something that takes a form that is fundamentally reliant on the network, I come up short. Maybe it would look like a hyper-extended comic ‘jams’, with panels by different artists on an evolving storyline. Maybe the form of a networked comic is something like a wiki with drawing tools. Or better yet, an instruction to the crowd that results in something like Sheep Market or swarmsketch. It’s interesting to see what “art from the mob” looks like, and seems to have the greatest potential for group-directed authorship. Maybe it will be something like magnetic word art (those word magnets you find on your friend’s fridge and use to write non-sensical and slightly naughty phrases with), combined with some sort of automatic image search. Obviously there are a lot of possibilities if you are willing to cede a little of the artistic control that tends to be so tightly wound up in the traditional method of making comics. I hate to end my posts with “we need more experiments!” but given the current state of the discussion, that’s just what I have to do.

digital comics

If you want to learn how to draw comics you can go to the art section of any bookstore and pick up books that will tell you how to draw the marvel way, how to draw manga, how to draw cutting edge comics, how to draw villains, women, horror, military, etc. But drawing characters is different than making comics. Will Eisner was the generator of the term ‘sequential art’ and the first popular theory of comics. Scott McCloud is his recent successor. Eisner created the vocabulary of sequential art in his long-running course at the School of Visual Arts in NYC. McCloud helped a generation of comic book readers grasp that vocabulary in Understanding Comics, by creating a graphic novel that employed comic art to explain comic theory. But both Eisner and McCloud wrote about a time when comic delivery was bound to newspapers and twenty-two page glossy, stapled pages.

Whither the network? McCloud treats the possibilities of the Internet in his second book, Reinventing Comics, but mostly as a distribution mechanism. We shouldn’t overlook the powerful affect the ‘net has had on individual producers who, in the past, would have created small runs of photocopied books to distribute locally. Now, of course, they can put their panels on the web and have a potential audience of millions. Some even make a jump from the web into print. Most web comics are sufficiently happy to ride the network to a wider audience without exploring the ‘net as vehicle to transform comics into uniquely non-print artifacts with motion, interactivity, sound.

But how might comics mutate on the web? At the recent ITP Spring show I saw a digital comics project from Tracy Ann White’s class. The class asks the question: “What happens when comics evolve from print to screen? How does presentation change to suit this shift?” Sounds like familiar territory. White, a teacher at ITP, has been a long time web comic artist (one of the first on the web, and certainly one of the first to incorporate comments and forums as part of the product.

When I did a little research on her, I found an amazing article on Webcomics Review discussing the history of web comics. (There’s also more from White there.) There has been some brilliant work done, making use of scrolling as part of the “infinite canvas,” but more importantly, work that could have no print analog due the incorporation of sound and motion. The discussion in Webcomics Review covers all of the transformative effects of online publishing that we talk about here at the Institute: interlinking, motion, sound, and more profoundly, the immediacy and participative aspects of the network. As an example, James Kochalka, well known for his Monkey vs. Robot comics and a simplistic cartoon style, publishes An American Elf. The four panel personal vignette is published daily-blogging with comics.

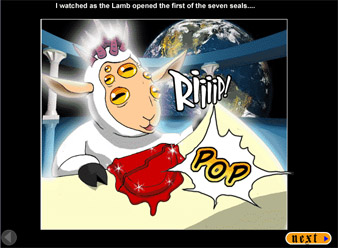

Other ground breaking work: Nowhere Girl by Justine Shaw, a long form graphic novel that proved that people will read lengthy comics online. Apocamon by Patrick Farley, is a mash up of Pokemon and The Book of Revelations. There is a well known series of bible stories in comic strip format – this raises that tradition to the level of heavenly farce (with anime). Apocamon judiciously uses sound and minor animation effects to create a rich reading experience, but relies on pages—a mode immediately familiar to comic book readers. The comics on Magic Inkwell (Cayetano Garza) use music and motion graphics in a more experimental way. And in Broken Saints we find an example where comic conventions (words in a comic style font, speech bubbles, and sequential images) fade into cinema.

As new technology enables stylistic enhancements to web comics, the boundaries between comics and other media will become more blurred. White says, “In terms of pushing interactive storytelling online games are at the forefront.” This is true, but online games dispense with important conventions that make comics comics. The next step for online comics is to enhance their networked and collaborative aspect while preserving the essential nature of comics as sequential art.

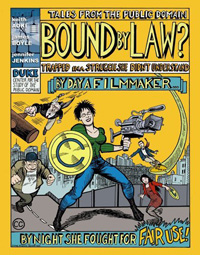

copyright debates continues, now as a comic book

Keith Aoki, James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins have produced a comic book entitled, “Bound By Law? Trapped in a Sturggle She Didn’t Understand” which portrays a fictional documentary filmmaker who learns about intellectual property, copyright and more importantly her rights to use material under fair use. We picked up a copy during the recent conference on “Cultural Environmentalism at 10” at Stanford. This work was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the same people who funded “Will Fair Use Survive?” from the Free Expression Policy Project of the Brennan Center at the NYU Law School, which was discussed here upon its release. The comic book also relies on the analysis that Larry Lessig covered in “Free Culture.” However, these two works go into much more detail and have quite different goals and audiences. With that said, “Bound By Law” deftly takes advantage of the medium and boldly uses repurposed media iconic imagery to convey what is permissible and to explain the current chilling effect that artists face even when they have a strong claim of fair use.

Keith Aoki, James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins have produced a comic book entitled, “Bound By Law? Trapped in a Sturggle She Didn’t Understand” which portrays a fictional documentary filmmaker who learns about intellectual property, copyright and more importantly her rights to use material under fair use. We picked up a copy during the recent conference on “Cultural Environmentalism at 10” at Stanford. This work was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the same people who funded “Will Fair Use Survive?” from the Free Expression Policy Project of the Brennan Center at the NYU Law School, which was discussed here upon its release. The comic book also relies on the analysis that Larry Lessig covered in “Free Culture.” However, these two works go into much more detail and have quite different goals and audiences. With that said, “Bound By Law” deftly takes advantage of the medium and boldly uses repurposed media iconic imagery to convey what is permissible and to explain the current chilling effect that artists face even when they have a strong claim of fair use.

Part of Boyle’s original call ten years ago for a Cultural Environmentalism Movement was to shift the discourse of IP into the general national dialogue, rather than remain in the more narrow domain of legal scholars. To that end, the logic behind capitalizing on a popular culture form is strategically wise. In producing a comic book, the authors intend to increase awareness among the general public as well as inform filmmakers of their rights and the current landscape of copyright. Using the case study of documentary film, they cite many now classic copyright examples (for example the attempt to use footage of a television in the background playing the”Simpsons” in a documentary about opera stagehands.) “Bound By Law” also leverages the form to take advantage of compelling and repurposed imagery (from Mickey Mouse to Mohammed Ali) to convey what is permissible and the current chilling effect that artists face in attempting to deal with copyright issues. It is unclear if and how this work will be received in the general public. However, I can easily see this book being assigned to students of filmmaking. Although, the discussion does not forge new ground, its form will hopefully reach a broader audience. The comic book form may still be somewhat fringe for the mainstream populus and I hope for more experiments in even more accesible forms. Perhaps the next foray into the popular culture will an episode of CSI or Law & Order, or a Michael Crichton thriller.

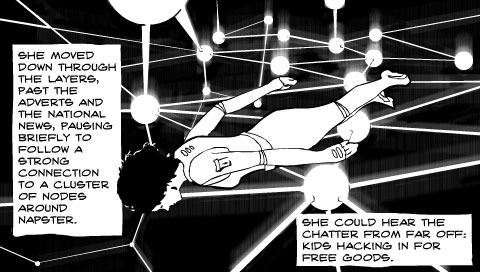

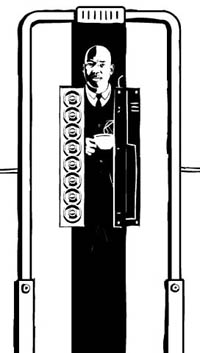

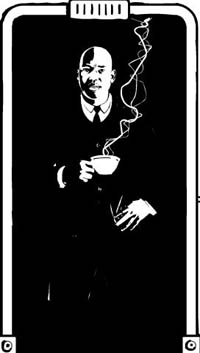

nyc2123: a graphic novel for psp

NYC2123 is a graphic novel conceived for the 480 by 272-pixel screen of the Play Station Portable video game device. It’s a post-apocalyptic tale set in a future, tsunami-ravaged New York in which the city’s wealthy have walled off the island of Manhattan against a violent river society of junkies, thieves and outlaw barges.

There are several sequences that read like a flip book, taking advantage of the single-frame interface and the fact that the reader has literally got his finger on the button. Quickly flipping through the panels creates a filmic effect, as here:

![]()

![]()

(Once again via Infocult – thanks Bryan)

Update: Someone has just developed a .pdf reader for the PSP.