On my way to that rather long discussion of ARGs the other day, I fielded something Pat Kane said to me a while back about the growing importance of live gigs to the income of musicians.

So I was tickled when Paul Miller pointed me to a piece Chris Anderson blogged yesterday about the same thing. Increasingly, musicians are giving their music away for free in order to drive gig attendance – and it’s driving music reproduction companies crazy. And yet, what can they do? “The one thing that you can’t digitize and distribute with full fidelity is a live show”.

A minor synchronicity; but then I stop by here and find Gary Frost and bowerbird vigorously debating the likeliness of the digitisation of everything, and of the death of ‘the original’ as even a concept, in the context of Ben’s piece about the National Archives sellout. And then I remember that, the day before, someone sent me a spoof web page telling me to get a First Life. And I start to wonder if there’s some kind of post-digital backlash taking shape.

OK, Anderson is talking about music; it’s hard to speculate about how the manifest ‘authentic’ appeal of a time-bound, ephemeral ‘gig’ experience translates literally to the field of physical books without falling back into diaphanous stuff about tactility and marginalia and so on. But, in the light of people’s manifest willingness to pay ridiculous sums to see the ‘real’ Madonna in real time and space, is it really feasible to talk, as bowerbird does, about the coming digitisation of everything?

As far as I can see, as more digitisation progresses, authenticity is becoming big business. I think it’s worth exploring the possibilities of a split between ‘book’ as pure content, and book as ‘authentic’ object. In particular, I think it’s worth exploring the possible economics of this: the difference in approach, genesis, theory, self-justification, style and paycheque of content created for digital reproduction, and text created for tangible books. And finally, I think whoever manages to sus both has probably got it made.

Category Archives: books

the sea change is coming…

Eons ago, when the institute was just starting out, Ben and I attended a web design conference in Amsterdam where we had the good fortune to chat with Steven Pemberton about the future of the book. Pemberton’s prediction, that “the book is doomed,” was based on the assumption that screen technologies would develop as printer technologies had. When the clunky dot-matrix gave way to the high-quality laser printer, desk top publishing was born and an entire industry changed form almost overnight.

“The book, Pemberton contends, will experience a similar sea-change the moment screen technology improves enough to compete with the printed page.”

This seemed like a logical conclusion. It seemed like the screen technology innovations we were waiting for had to do with resolution and legibility. Over the last two years if:book has reported on digital ink and other innovations that seemed promising. But the fact that we were looking out for a screen technology that could “compete with the printed page,” made it difficult for us to see that the real contender was not page-like at all.

It’s interesting that we made the same assumptions about the structure of the ebook itself. Early ebook systems tried to compete with the book by duplicating conventions like the Table of Contents navigational strategy, and discreet “pages,” that have to be “turned” with the click of a mouse. (And, I’m sorry to report, most contemporary ebooks continue to cling to print book structure). We now understand that networked technologies can interface with book content to create entirely new and revolutionary delivery systems. The experiments the institute has conducted: “Gam3r Th30ry” and the “Iraq Quagmire Project” prove beyond question that the book is evolving and adapting to networked culture.

What kind of screen technology will support this new kind of book? It appears that touch-screen hardware paired with zooming interface software will be the tipping point Pemberton was anticipating. There are many examples of this emerging technology. In particular, I like Jeff Han’s experimental work (his TED presentation is below): Jeff demonstrates an “interface free” touch screen that responds to gesture and lets users navigate through a simulated 3D environment. This technology might allow very small surfaces (like the touchpads on hand-held devices) to act as portals into limitless deep space.

And that brings me around to the real reason the touchscreen zooming interface is the key to the next generation of “books.” It allows users to move into 3D networked space easily and fluently and it gets us beyond the linearity that is the hallmark and the limitation of the paper book. To come into its own, the networked book is going to require three-dimensional visualizations for both content and navigation. Here’s an example of how it might work, imagine the institute’s Iraq Study Group Report in 3D. Main authors would have nodes or “homesites” close to the book with threads connecting them to sections they authored. Co-authors/commentors might have thinner threads that extend out to their, more remotely located, sites. The 3D depiction would allow readers to see “threads” that extend out from each author to everything they have created in digital space. In other words, their entire network would be made visible. Readers could know an author’s body of work in a new way and they could begin to see how collaborative works have been understood and shaped by each contributor. It would be ultimate transparency. It would be absolutely fascinating to see a 3D visualization of other works and deeds by the Iraq Study Groups’ authors, and to “see” the interwoven network spun by Washington’s policy authors. Readers could zoom out to get a sense of each author’s connections. Imagine being able to follow various threads into territories you never would have found via other, more conventional routes. This makes me really curious about what the institute will do in Second Life. I wonder if you can make avatars that act as the nodes for all their threads? Perhaps they could go about like spiders, connecting strands to everything they touch? Hmmm.

But anyway, in my humble opinion the sea change is coming. It’s going to be three-pronged: screen technology, networked content, and 3D visualization. And it’s going to be very, very cool.

atomization

During three different conversations during the holidays people told me “i’m reading more now, not less.” referring not to books, but rather time spent surfing the net and reading email. Given my interest in the “future of the book” i think people say this sort of thing to me somewhat guiltily, trying to cover for the unstated concern that all reading might not be equal. I’m not even close to wanting to make a value judgement in this regard, but the following quote from yesterday’s NY Times article suggests that for those of us living in the world of near infinite media choice, the social role of the (print) book has undergone a dramatic transformation.

PRINCETON, N.J., Dec. 29 — Logan Fox can’t quite pinpoint the moment when movies and television shows replaced books as the cultural topics people liked to talk about over dinner, at cocktail parties, at work. He does know that at Micawber Books, his 26-year-old independent bookstore here that is to close for good in March, his own employees prefer to come in every morning and gossip about “Survivor” or “that fashion reality show” whose title he can’t quite place.

BUT HAS IT? My guess is that this change started more than 75 years ago with the ascendancy of broadcast media, movies, radio and tv, rather than with the rise of the net. My further guess is that if he had listened carefully 26 years ago when he opened the store, Logan Fox would have overheard discussions about movies and tv-shows in perhaps the same proportions as today. If anything is different today, I think it’s the atomization of choice. When i talk with friends, most of whom swim in the vast media ocean, we often have trouble finding something that all of us have watched, listened to or read. This seems to be the more signficant shift with potentially profound implications for society going forward.

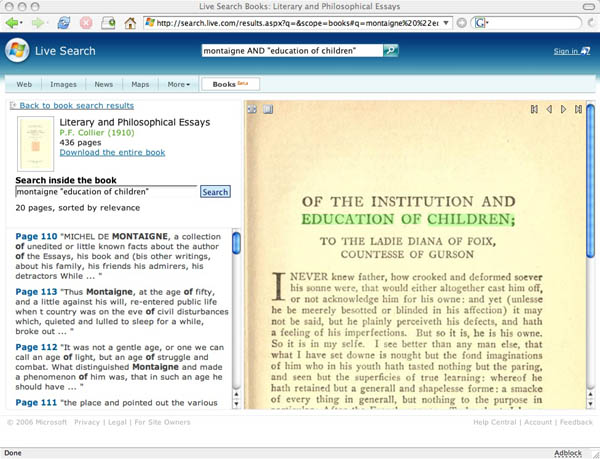

microsoft launches live search books

Windows Live Search Books, Microsoft’s answer to Google Book Search, is officially up and running and looks and feels pretty much the same as its nemesis. Being a Microsoft product, the interface is clunkier, and they have a bit of catching up to do in terms of navigation and search options. The one substantive difference is that Live Search is mostly limited to out-of-copyright books — i.e. pre-19231927 editions of public domain works. So the little they do have in there is fully accessible, with PDFs available for download. Like Google’s public domain books, however, the scans are of pretty poor quality, and not searchable. Readers point out that Microsoft, unlike Google, does in fact include a layer of low-quality but entirely searchable OCR text in its public domain downloads.

readers dead?

From a new Bookforum interview, this is Gore Vidal’s rather grim take on the place of the novel — or novelist — in public life:

BOOKFORUM: You write in Point to Point Navigation that you were once a “famous novelist,” by which you don’t mean you’ve stopped writing novels. You say, “To speak today of a famous novelist is like speaking of a famous cabinetmaker or speedboat designer.”

GORE VIDAL: Yes. There’s no such thing as a famous novelist.

BF: But what about a writer like Salman Rushdie?

GV: He’s moderately well known, but he’s not read by a large public. He’s very good, but “famous” has nothing to do with being good or bad.

BF: A few critics have declared the American novel dead.

GV: I don’t think the novel is dead. I think the readers are dead. The novel doesn’t interest anybody, and that’s largely because there are no famous novelists. Fame means that you are touching everybody or potentially touching everybody with what you’ve done–that they like to think about it and talk about it and exchange views on it.

It’s interesting to consider that that particular kind of 1950s fame that Vidal the novelist (he wears many hats) so enjoyed may have had less to do with the novel as a form and more to do with the celebrity culture of television, where, at that time, a serious literary writer could rank among the gods. Perhaps what Vidal, fallen from Olympus, really is lamenting is the passing of a brief but charmed period of media convergence where books were strangely served, rather than undermined (the conventional narrative), by television.

BF: Novelists used to work the nightly talk-show circuit. It’s hard to believe that there was a time in this country when writers were regarded as celebrities.

GV: I started all of that. I was the first novelist to go on television back in the ’50s, on The Jack Paar Show and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

At that time, the power of television was concentrated in a tiny handful of big networks. People shared a small constellation of cultural reference points in a mass media market. Then came cable, the internet, YouTube, the long tail. Is today’s reading public really dead or just more atomized? Have our ways of reading become fragmented to the point that we can no longer be touched all at once by a single creative vision — or visionary?

But wait — couldn’t Oprah, if she chose, launch a book into the center of a national discussion? And what about the web? What can it do?

networked books and more at forbes

Get yourselves on over to Forbes.com and check out this lovely set of essays that editors Michael Maiello and Michael Noer have collected on the future (and present) of the book, including a piece by yours truly on the networked book. Bob is also quoted at length in this piece on the need to rethink copyright.

From the editors’ intro:

Are books in danger?

The conventional wisdom would say yes. After all, more and more media–the Internet, cable television, satellite radio, videogames–compete for our time. And the Web in particular, with its emphasis on textual snippets, skimming and collaborative creation, seems ill-suited to nurture the sustained, authoritative transmission of complex ideas that has been the historical purview of the printed page.

But surprise–the conventional wisdom is wrong. Our special report on books and the future of publishing is brim-full of reasons to be optimistic. People are reading more, not less. The Internet is fueling literacy. Giving books away online increases off-line readership. New forms of expression–wikis, networked books–are blossoming in a digital hothouse.

People still burn books. But that only means that books are still dangerous enough to destroy. And if people want to destroy them, they are valuable enough that they will endure.

on today’s publications

On November 27 the Pulitzer Prize Board announced that “newspapers may now submit a full array of online material-such as databases, interactive graphics, and streaming video-in nearly all of its journalism categories,” while the closest The New York Times’ 100 Notable Books of the Year came to documenting any changes in the publishing world is one graphic memoir (Fun Home by Alison Bechdel.)

On November 27 the Pulitzer Prize Board announced that “newspapers may now submit a full array of online material-such as databases, interactive graphics, and streaming video-in nearly all of its journalism categories,” while the closest The New York Times’ 100 Notable Books of the Year came to documenting any changes in the publishing world is one graphic memoir (Fun Home by Alison Bechdel.)

Only last year the Pulitzer Prize Board allowed for the first time some online content, but now, it will permit a broader, and much more current assortment of online elements, according to the different Pulitzer categories. The seemingly obvious restrictions are for photography, which permit still images only. They have decided to catch up with the times: “This board believes that its much fuller embrace of online journalism reflects the direction of newspapers in a rapidly changing media world,” said Sig Gissler, administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes. With its new rules for online submissions, the Pulitzer Board acknowledges that online elements such as a database, blog, interactive graphic, slide show, or video presentation count as items in the total number of elements, print or online, that can be considered worth a prize.

Even though the use of multimedia and computer technology has become ubiquitous not only in the media world but also in the performing arts, the book world seems absorbed in its own universe. The notion of “digital book” continues to mean digital copies of books and the consequent battle among those who want the lion’s share of the market (see “Yahoo Rebuffs Google on Digital Books”). And, when we talk about ebooks we mean devices for reading digital copies of books. Interestingly, most of the books published today are written, composed and set using electronic technology. So much of what we read online is full of distracting, sometimes quite interesting, advertising. On Black Friday, lots of people following the American tradition of shopping on that day did it online. It would seem that we are more than ready for real ebooks. I wonder how long it would take for one of them to hit the top lists of the year.

dotReader is out

dotReader, “an open source, cross-platform content reader/management system with an extensible, plug-in architecture,” is available now in beta for Windows and Linux, and should be out for Mac any day now. For now, dotReader is just for reading but a content creation tool is promised for the very near future.

dotReader, “an open source, cross-platform content reader/management system with an extensible, plug-in architecture,” is available now in beta for Windows and Linux, and should be out for Mac any day now. For now, dotReader is just for reading but a content creation tool is promised for the very near future.

The reader has some nice features like shared bookmarks and annotations, a tab system for moving between multiple texts and an embedded web browser. In many ways it feels like a web browser that’s been customized for books. I can definitely see it someday becoming a fully web-based app. The recently released Firefox 2 has a bunch of new features like live bookmarks (live feed headlines in drop-down menus on your bookmarks toolbar) and a really nice embedded RSS reader. It’s a pretty good bet that online office suites, web browsers and standalone reading programs are all on the road to convergence.

Congrats to the OSoft team and to David Rothman of Teleread, who has worked with them on implementing the Open Reader standard in dotReader.

russian ideas, british delivery

This weekend I watched a performance of Voyage, the first part of Tom Stoppard’s new trilogy, The Coast of Utopia. It’s pure Stoppard: erudition delivered in a crossfire of dialogue and movement, skipping through time like a smartly thrown stone.

It is the story of young Russian intellectuals—Michael Bakunin, Nickolai Stankevich, Vissarion Belinsky, Alexander Herzen, Ivan Turgenev, Nicholas Ogarev—discovering foreign philosophy during the time of Tsar Nicholas I (a particularly conservative government). The young men, driven by Bakunin (played by Ethan Hawke), investigate the philosophies of Kant, Schelling, Goethe, Fichte, and Hegel. Bakunin ferociously pursues each philosopher and sprays his new knowledge at everyone he knows—most significantly his four sisters. By sharing books, writing letters, and expounding during summer visits to the family home he becomes the main vector of change in their lives. This first play is as much about the sisters’ struggle to withstand the shifting currents of MIchael’s idealism as it is about the early days of Russian intellectualism, or the last days of slavery in Russia, or the collision between ideas and reality.

Stoppard weaves these different themes together so deftly you can hardly tell where one ends and another begins. More importantly, it’s difficult to see how you could have one absent the others. The first act of the play is set at Premukhino, the Bakunin family estate, over the course of seven years. A phalanx of ragged bodies is set in the background, behind a sheer scrim representing the serfs. Their presence is constant, menacing, but generally unobtrusive to the Bakunin family, as they go about their own tumults brought on by one thing or another that Michael has done. At times you forget the serfs are there, and then, suddenly, you’ll look up and see the staggered rows of ragged bodies and a sense of foreboding descends.

The second act is set in Moscow, during the same seven years. Stoppard rewinds time to show us how events in the city led to the disruptions at Premukhino. The action in the city is invested with a sense of urgency, where the young men verbally joust as they try to define their latest position with regard to the newest book they’ve read. Moscow is a hotbed of anti-tsarist sentiment and foreign idealism. The political tension is high, the sensation of fear and revolt bubbles just below the surface. But Moscow is also an incubator for love, and it is there we witness the first real contact between humans, not just the meeting of like minds.

The play is a tour of European philosophy in the 1800’s, and it is highly ambitious (something you could say about any 9-hour trilogy, I suppose). But it is, nevertheless, gripping stuff. Billy Crudup does an amazing turn as Belinsky, completely inhabiting the character and committing to the moment. Ethan Hawke was fine as Bakunin, though his insouciance had a Reality Bites mopiness that seemed out of place in a young man who was struggling to bring Mother Russia into the modern era. The performance in the second act was more balanced and more powerful.

Prior to seeing the play I was concerned that the first act of a trilogy would have a sense of being open in the way a cliffhanger is open. I was watching it with two visitors from out of town, and it is unlikely they’ll be able to return to see Shipwrecked or Salvage. I didn’t want them to leave with a sense of the work being unfinished. While the action is indeed open-ended, there is a very strong sense of closure at the end of the second act. It is more portentous than unfinished: there is war and exile and a nobleman at the end of his life, contemplating the loss of his son and the dissolution of his estate. It is a nod to the great Russian novels, but with the unfussy delivery that I recognize from other Stoppard plays.

One of the things I kept noticing during the performance was the presence of books. When Stankevich passed a book to Bakunin, I felt the transfer of knowledge. The play expresses ideal of what we think about at the Institute: books as vehicles for big ideas. There is a treatise waiting to be written about the view of literature defining a nation (explosively presented in a monologue from Belinsky). And there is, throughout, a very powerful sense that the printed word is vastly important. But there is also that sense of impending loss, which makes us question where we are today. Do we live in a world where idealism is lost, and where the gilt-edged books filled with new philosophies are no longer valued? Or is it the opposite? Do we live in a world where the book is doing better than ever, and idealism takes so many forms that it is unrecognizable?

terrain as browsing mechanism

Ben’s post last week, book as terrain, about converting any image to an interactive map with hotspots contained a link to a blog which collects info about all sorts of google map mashups. Ben’s post was about using book pages as geographic jumping-off points. However, as i read the endlessly fascinating list of other sorts of mashups it occurred to me that in addition to “book as terrain” we could also look at the idea of “Google map mashups” as a genuinely new form of expression. As I read through the wonderfully annotated list I realized that they cover the full gamut of subjects you would find in a bookstore . . . . Fiction, Non-Fiction, Travel, History, Sports, Games, Religion, Personal Growth, and Crime.

It’s interesting to realize that as our experience moves relentlessly into the virtual domain, that geography, which in the past was firmly rooted in the “real,” increasingly becomes the mechanism for organizing our activiites in virtual space.