If you’re in the New York area, this Wednesday I’ll be giving a talk at an event organized by the Brooklyn College Library called “It’s All About the Book.” Also speaking will be Jason Epstein, one of the all-time great innovators in print publishing, and founder most recently of On Demand Books. Talks will be followed by a tour of “books as art” installations by a number of local artists, curators and librarians. It promises to be an interesting event, well worth the trek to Flatbush.

Category Archives: books

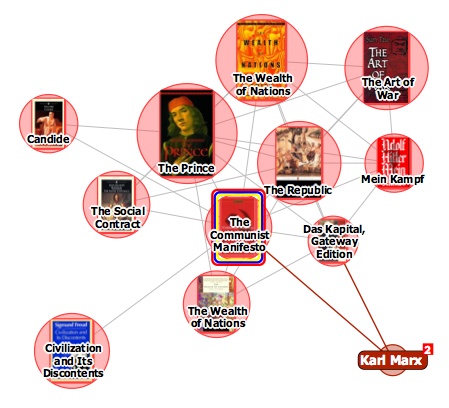

visual amazon browser

The interface design firm TouchGraph recently released a free visual browsing tool for Amazon’s books, movies, music and electronics inventories. My first thought was, aha, here’s a tool that can generate an image of Bob’s thought experiment, which reimagines The Communist Manifesto as a networked book, connected digitally to all the writings it has influenced and all the commentaries that have been written about it. Alas no.

It turns out that relations between items in the TouchGraph clusters are based not on citations across texts but purely on customer purchase patterns, the data that generates the “customers who bought this item also bought” links on Amazon pages. The results, consequently, are a tad shallow. Above you see The Communist Manifesto situated in a small web of political philosophy heavyweights, an image that reveals more about Amazon’s algorithmically derived recommendations than any actual networks of discourse.

TouchGraph has built a nice tool, and I’m sure with further investigation it might reveal interesting patterns in Amazon reading (and buying) behaviors (in the electronics category, it could also come in handy for comparison shopping). But I’d like to see a new verion that factors in citation indexes for books – data that Amazon already provides for many of its titles anyway. They could also look at user-supplied tags, Listmania lists, references from reader reviews etc. And perhaps with the option to view clusters across media types, not simply broken down into book, movie and music categories.

the people’s card catalog (a thought)

New partners and new features. Google has been busy lately building up Book Search. On the institutional end, Ghent, Lausanne and Mysore are among the most recent universities to hitch their wagons to the Google library project. On the user end, the GBS feature set continues to expand, with new discovery tools and more extensive “about” pages gathering a range of contextual resources for each individual volume.

Recently, they extended this coverage to books that haven’t yet been digitized, substantially increasing the findability, if not yet the searchability, of thousands of new titles. The about pages are similar to Amazon’s, which supply book browsers with things like concordances, “statistically improbably phrases” (tags generated automatically from distinct phrasings in a text), textual statistics, and, best of all, hot-linked lists of references to and from other titles in the catalog: a rich bibliographic network of interconnected texts (Bob wrote about this fairly recently). Google’s pages do much the same thing but add other valuable links to retailers, library catalogues, reviews, blogs, scholarly resources, Wikipedia entries, and other relevant sites around the net (an example). Again, many of these books are not yet full-text searchable, but collecting these resources in one place is highly useful.

It makes me think, though, how sorely an open source alternative to this is needed. Wikipedia already has reasonably extensive articles about various works of literature. Library Thing has built a terrific social architecture for sharing books. There are a great number of other freely accessible resources around the web, scholarly database projects, public domain e-libraries, CC-licensed collections, library catalogs.

Could this be stitched together into a public, non-proprietary book directory, a People’s Card Catalog? A web page for every book, perhaps in wiki format, wtih detailed bibliographic profiles, history, links, citation indices, social tools, visualizations, and ideally a smart graphical interface for browsing it. In a network of books, each title ought to have a stable node to which resources can be attached and from which discussions can branch. So far Google is leading the way in building this modern bibliographic system, and stands to turn the card catalogue of the future into a major advertising cash nexus. Let them do it. But couldn’t we build something better?

promiscuous materials

This began as a quick follow-up to my post last week on Jonathan Lethem’s recent activities in the area of copyright activism. But after a couple glasses of sake and some insomnia it mutated into something a bit bigger.

Back in March, Lethem announced that he planned to give away a free option on the film rights of his latest novel, You Don’t Love Me Yet. Interested filmmakers were invited to submit a proposal outlining their creative and financial strategies for the project, provided that they agreed to cede a small cut of proceeds if the film ends up getting distributed. To secure the option, an artist also had to agree up front to release ancillary rights to their film (and Lethem, likewise, his book) after a period of five years in order to allow others to build on the initial body of work. Many proposals were submitted and on Monday Lethem granted the project to Greg Marcks, whose work includes the feature “11:14.”

What this experiment does, and quite self-consciously, is demonstrate the curious power of the gift economy. Gift giving is fundamentally a ritual of exchange. It’s not a one-way flow (I give you this), but a rearrangement of social capital that leads, whether immediately or over time, to some sort of reciprocation (I give you this and you give me something in return). Gifts facilitate social equilibrium, creating occasions for human contact not abstracted by legal systems or contractual language. In the case of an artistic or scholarly exchange, the essence of the gift is collaboration. Or if not a direct giving from one artist to another, a matter of influence. Citations, references and shout-outs are the acknowledgment of intellectual gifts given.

By giving away the film rights, but doing it through a proposal process which brought him into conversation with other artists, Lethem purchased greater influence over the cinematic translation of his book than he would have had he simply let it go, through his publisher or agent, to the highest bidder. It’s not as if novelists and directors haven’t collaborated on film adaptations before (and through more typical legal arrangements) but this is a significant case of copyright being put to the side in order to open up artistic channels, changing what is often a business transaction — and one not necessarily even involving the author — into a passing of the creative torch.

Another Lethem experiment with gift economics is The Promiscuous Materials Project, a selection of his stories made available, for a symbolic dollar apiece, to filmmakers and dramatists to adapt or otherwise repurpose.

One point, not so much a criticism as an observation, is how experiments such as these — and you could compare Lethem’s with Cory Doctorow’s, Yochai Benkler’s or McKenzie Wark’s — are still novel (and rare) enough to serve doubly as publicity stunts. Surveying Lethem’s recent free culture experiments it’s hard not to catch a faint whiff of self-congratulation in it all. It’s oh so hip these days to align one’s self with the Creative Commons and open source culture, and with his recent foray into that arena Lethem, in his own idiosyncratic way, joins the ranks of writers shrewdly riding the wave of the Web to reinforce and even expand their old media practice. But this may be a tad cynical. I tend to think that the value of these projects as advocacy, and in a genuine sense, gifts, outweighs the self-promotion factor. And the more I read Lethem’s explanations for doing this, the more I believe in his basic integrity.

It does make me wonder, though, what it would mean for “free culture” to be the rule in our civilization and not the exception touted by a small ecstatic sect of digerati, some savvy marketers and a few dabbling converts from the literary establishment. What would it be like without the oppositional attitude and the utopian narratives, without (somewhat paradoxically when you consider the rhetoric) something to gain?

In the end, Lethem’s open materials are, as he says, promiscuities. High-concept stunts designed to throw the commodification of art into relief. Flirtations with a paradigm of culture as old as the Greek epics but also too radically new to be fully incorporated into the modern legal-literary system. Again, this is not meant as criticism. Why should Lethem throw away his livelihood when he can prosper as a traditional novelist but still fiddle at the edges of the gift economy? And doesn’t the free optioning of his novel raise the stakes to a degree that most authors wouldn’t dare risk? But it raises hypotheticals for the digital age that have come up repeatedly on this blog: what does it mean to be a writer in the infinitely reproducible non-commodifiable Web? what is the writer after intellectual property?

gamer theory 2.0

…is officially live! Check it out. Spread the word.

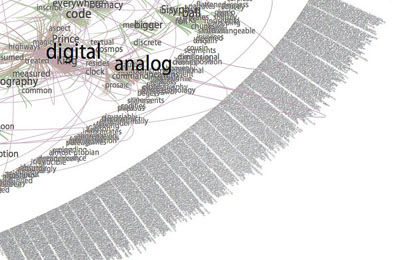

I want to draw special attention to the Gamer Theory TextArc in the visualization gallery – a graphical rendering of the book that reveals (quite beautifully) some of the text’s underlying structures.

Gamer Arc detail

TextArc was created by Brad Paley, a brilliant interaction designer based in New York. A few weeks ago, he and Ken Wark came over to the Institute to play around with the Gamer Theory in TextArc on a wall display:

Ken jotted down some of his thoughts on the experience: “Brad put it up on the screen and it was like seeing a diagram of my own writing brain…” Read more here (then scroll down partway).

starting bottom-left, counter-clockwise: Ken, Brad, Eddie, Bob

More thoughts about all of this to come. I’ve spent the past two days running around like a madman at the Digital Library Federation Spring Forum in Pasadena, presenting our work (MediaCommons in particular), ducking in and out of sessions, chatting with interesting folks, and pounding away at the Gamer site — inserting footnote links, writing copy, generally polishing. I’m looking forward to regrouping in New York and processing all of this.

Thanks, Florian Brody for the photos.

Oh, and here is the “official” press/blogosphere release. Circulate freely:

The Institute for the Future of the Book is pleased to announce a new edition of the “networked book” Gamer Theory by McKenzie Wark. Last year, the Institute published a draft of Wark’s path-breaking critical study of video games in an experimental web format designed to bring readers into conversation around a work in progress. In the months that followed, hundreds of comments poured in from gamers, students, scholars, artists and the generally curious, at times turning into a full-blown conversation in the manuscript’s margins. Based on the many thoughtful contributions he received, Wark revised the book and has now published a print edition through Harvard University Press, which contains an edited selection of comments from the original website. In conjunction with the Harvard release, the Institute for the Future of the Book has launched a new Creative Commons-licensed, social web edition of Gamer Theory, along with a gallery of data visualizations of the text submitted by leading interaction designers, artists and hackers. This constellation of formats — read, read/write, visualize — offers the reader multiple ways of discovering and building upon Gamer Theory. A multi-mediated approach to the book in the digital age.

http://web.futureofthebook.org/mckenziewark/

More about the book:

Ever get the feeling that life’s a game with changing rules and no clear sides, one you are compelled to play yet cannot win? Welcome to gamespace. Gamespace is where and how we live today. It is everywhere and nowhere: the main chance, the best shot, the big leagues, the only game in town. In a world thus configured, McKenzie Wark contends, digital computer games are the emergent cultural form of the times. Where others argue obsessively over violence in games, Wark approaches them as a utopian version of the world in which we actually live. Playing against the machine on a game console, we enjoy the only truly level playing field–where we get ahead on our strengths or not at all.

Gamer Theory uncovers the significance of games in the gap between the near-perfection of actual games and the highly imperfect gamespace of everyday life in the rat race of free-market society. The book depicts a world becoming an inescapable series of less and less perfect games. This world gives rise to a new persona. In place of the subject or citizen stands the gamer. As all previous such personae had their breviaries and manuals, Gamer Theory seeks to offer guidance for thinking within this new character. Neither a strategy guide nor a cheat sheet for improving one’s score or skills, the book is instead a primer in thinking about a world made over as a gamespace, recast as an imperfect copy of the game.

——————-

The Institute for the Future of the Book is a small New York-based think tank dedicated to inventing new forms of discourse for the network age. Other recent publishing experiments include an annotated online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report (with Lapham’s Quarterly), Without Gods: Toward a History of Disbelief (with Mitchell Stephens, NYU), and MediaCommons, a digital scholarly network in media studies. Read the Institute’s blog, if:book. Inquiries: curator [at] futureofthebook [dot] org

McKenzie Wark teaches media and cultural studies at the New School for Social Research and Eugene Lang College in New York City. He is the author of several books, most recently A Hacker Manifesto (Harvard University Press) and Dispositions (Salt Publishing).

gamer theory update

Gamer Theory 2.0 is nearly there, we’re just taking a few extra few days to apply the finishing touches and to get a few last visualizations mounted in the gallery. The print edition from Harvard is available now.

For those of you in the city, there’s a great Gamer Theory event planned for tonight at the New School followed by drinks in Brooklyn at Barcade — a bar (as the name suggests) fitted out as a retro video game arcade (have a pint and play a round of Rampage, Gauntlet or Frogger). Here’s more info:

what: McKenzie Wark will present, and lead a discussion of his new book Gamer Theory (Harvard University Press). Jaeho Kang (Sociology, The New School for Social Reseach) will act as the respondent.

where: Wolff Conference Room, 2nd floor, 65 5th avenue (between 14th and 13th streets)

when: 6-8PM, Wednesday 18th April 2007

then: drinks & games at Barcade, 388 Union Ave Williamsburg (L train to Lorrimer st, take Union exit)

samizdat express

In his latest NY Times column, Edward Rothstein meditates on the vastness of the public domain and the pleasures of skimming it in simple digital editions prepared by B+R Samizdat Express. Since 1993 B+R, run by Barbara and Richard Seltzer of West Roxbury, Massachusetts, has been selling bundles of plain text (ASCII) digital literature scooped from Project Gutenberg and arranged by theme, genre or period into anthologies — first on floppy disc, and now on CD-ROM and DVD. It’s all stuff you can get for free by grazing the web’s various public domain repositories, but B+R have done the work of harvesting and sorting and they’ll ship these multi-shelf-spanning chunks to you for the price of a single print volume. Browse through nearly 200 book collections they’ve assembled so far and you’ll find packages ranging from “Anthropology and Myth” ($19), “Works of Guy de Maupassant” ($12), or “The American Revolution and Early Republic as witnessed by Mercy Warren and Others” ($19). Some works are provided in audio through text-to-voice conversion software.

As Rothstein notes, the bare-bones formatting and sheer volume of the anthologies makes these works hard to digest, but there’s no doubt B+R provides a valuable service, especially for people in places where books are scarce and net access unreliable. All in all, it’s an e-book advocate’s playground but more of a hallucinogenic head trip for the average reader — a way to sample vastness. It does make one’s wheels start to turn, though, on what other elucidating layers could be built on top of the vast murk of the digital library.

noonebelongsheremorethanyou

josh portway sent a note today saying “i have found the future of the book” which included a link to a delightfully charming site made by Miranda July to tout her new book of short stories. It’s interesting to note how the low-tech mode of expression works so brilliantly in the high tech context of the browser.

already born digital

Joan Acocella has an interesting review in The New Yorker of Darren Wershler-Henry’s recent book The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting (previously discussed here on if:book). It’s worth a look just for all the juicy backstory it delivers on the typewriter as well as accounts of various writers’ intense, sometimes haunted, relationships with their machines. But Acocella also delves into an important area that apparently gets only passing consideration in the book — the way writing has changed since the advent of computers. Reading this makes you remember that with word processors we’ve all been writing “born digital” texts for quite some time:

Joan Acocella has an interesting review in The New Yorker of Darren Wershler-Henry’s recent book The Iron Whim: A Fragmented History of Typewriting (previously discussed here on if:book). It’s worth a look just for all the juicy backstory it delivers on the typewriter as well as accounts of various writers’ intense, sometimes haunted, relationships with their machines. But Acocella also delves into an important area that apparently gets only passing consideration in the book — the way writing has changed since the advent of computers. Reading this makes you remember that with word processors we’ve all been writing “born digital” texts for quite some time:

Mallarmé spoke of the uncertainty with which we face a clean sheet of paper and try, in vain, to record our thoughts on it with some precision. As long as we were feeding paper into a typewriter, this anxiety was still present to our minds, and was revealed in the pointillism of Wite-Out, or even in the dapple of letters that were darker, pressed in confidence, as opposed to the lighter ones, pressed more hesitantly. A page produced on a manual typewriter was like a record of the torture of thought. With the P.C., the situation is altogether different. The screen, a kind of indeterminate space, does not seem violable in the same way as the page. And, because what we write on it is so effortlessly and undetectably erasable, the final text buries the evidence of our struggle, asserting that what we said was what we thought all along. Wershler-Henry suggests that the P.C.–with some help from Derrida and Baudrillard–ushered us into a world in which the difference between true and false is no longer cause for doubt or grief; falsity is taken for granted. I don’t know if he was thinking about the spurious perfection of the computer-generated page, but it would be a useful example.

Something else to think about is the effect that the computer, with its astonishing capabilities, has had on us as writers. Take just one example: the ease of moving a block of text. Highlight, hit control X, move cursor, hit control V, and, presto, that paragraph is in a new place. Of course, we were able to move things in typewritten text, too, but all that business with the scissors and the tape made us think twice, and maybe it was wise for us to hesitate before changing the order in which our brains produced our thoughts. In recent years, I have read a lot of writings that seemed to say, “This paragraph is here because it seemed an O.K. place to shove it in.” Furthermore, by allowing us to move text easily, computers influence us to write in movable units. In the novel that won Britain’s Booker Prize last year, Kiran Desai’s “The Inheritance of Loss,” there is a line space, indicating a break of thought, every three pages or so.

dismantling the book

Peter Brantley relates the frustrating experience of trying to hunt down a particular passage in a book and his subsequent painful collision with the cold economic realities of publishing. The story involves a $58 paperback, a moment of outrage, and a venting session with an anonymous friend in publishing. As it happens, the venting turned into some pretty fascinating speculative musing on the future of books, some of which Peter has reproduced on his blog. Well worth a read.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

Amazon already provides a by-the-page or by-the-chapter option for certain titles through its “Pages” program. Google presumably will hammer out some deals with publishers and offer a similar service before too long. Peter Osnos’ Caravan Project includes individual chapter downloads and print-on-demand as part of the five-prong distribution standard it is promoting throughout the industry. If this catches on, it will open up a plethora of options for readers but it might also unvravel the very notion of what a book is. Could we be headed for a replay of the mp3’s assault on the album?

The wholeness of the book has to some extent always been illusory, and reading far more fragmentary than we tend to admit. A number of things have clouded our view: the economic imperative to publish whole volumes (it’s more cost-effective to produce good aggregations of content than to publish lots of individual options, or to allow readers to build their own); romantic notions of deep, cover-to-cover reading; and more recently, the guilty conscience of the harried book consumer (when we buy a book we like to think that we’ll read the whole thing, yet our shelves are packed with unfinished adventures).

But think of all the books that you value just for a few particular nuggets, or the books that could have been longish essays but were puffed up and padded to qualify as $24.95 commodities (so many!). Any academic will tell you that it is not only appropriate but vital to a researcher’s survival to hone in on the parts of a book one needs and not waste time on the rest (I’ve received several tutorials from professors and graduate students on the fine art of fileting a monograph). Not all thoughts are book-sized and not all reading goes in a straight line. Selective reading is probably as old as reading itself.

Unbundling the book has the potential to allow various forms of knowledge to find the shapes and sizes that fit them best. And when all the pieces are interconnected in the network, and subject to social discovery tools like tagging, RSS and APIs, readers could begin to assume a role traditionally played by publishers, editors and librarians — the role of piecing things together. Here’s the bit of Peter’s conversation that goes into this:

Peter: …the Google- empowered vision of the “network of books” which is itself partially a romantic, academic notion that might actually be a distinctly net minus for publishers. Potentially great for academics and readers, but potentially deadly for publishers (not to mention librarians). As opposed to the simple first order advantage of having the books discoverable in the first place – but the extent to which books are mined and then inter-connected – that is an interesting and very difficult challenge for publishers.

Am I missing something…?

Friend: If you mean, are book publishers as we know them doomed? Then the answer is “probably yes.” But it isn’t Google’s connecting everything together that’s doing it. If people still want books, all this promotion of discovery will obviously help. But if they want nuggets of information, it won’t. Obviously, a big part of the consumer market that book publishers have owned for 200 years want the nuggets, not a narrative. They’re going, going, gone. The skills of a “publisher” — developing content and connecting it to markets — will have to be applied in different ways.

Peter: I agree that it is not the mechanical act of interconnection that is to blame but the demand side preference for chunks of texts. And the demand is probably extremely high, I agree.

The challenge you describe for publishers – analogous in its own way to that for libraries – is so fundamentally huge as to mystify the mind. In my own library domain, I find it hard to imagine profoundly differently enough to capture a glimpse of this future. We tinker with fabrics and dyes and stitches but have not yet imagined a whole new manner of clothing.

Friend: Well, the aggregation and then parceling out of printed information has evolved since Gutenberg and is now quite sophisticated. Every aspect of how it is organized is pretty much entirely an anachronism. There’s a lot of inertia to preserve current forms: most people aren’t of a frame of mind to start assembling their own reading material and the tools aren’t really there for it anyway.

Peter: They will be there. Arguably, when you look at things like RSS and Yahoo Pipes and things like that – it’s getting closer to what people need.

And really, it is not always about assembling pieces from many different places. I might just want the pieces, not the assemblage. That’s the big difference, it seems to me. That’s what breaks the current picture.

Friend: Yes, but those who DO want an assemblage will be able to create their own. And the other thing I think we’re pointed at, but haven’t arrived at yet, is the ability of any people to simply collect by themselves with whatever they like best in all available media. You like the Civil War? Well, by 2020, you’ll have battle reenactments in virtual reality along with an unlimited number of bios of every character tied to the movies etc. etc. etc. I see a big intellectual change; a balkanization of society along lines of interest. A continuation of the breakdown of the 3-television network (CBS, NBC, ABC) social consensus.