CustomFlix, Amazon’s on-demand DVD distribution service, has just been rebranded as CreateSpace, and will now serve up self-published media of all types. Getting a title into the system is free and relatively simple. Books must be a minimum of 24 pages and have to be submitted as a PDF. Seven trim sizes are available for color interiors, five for black and white. Each title automatically receives an ISBN and is displayed to shoppers as “in stock,” available for shipping immediately. You set the list price on your media, Amazon sets the selling price. CreateSpace is listed as the publisher of the book unless you provide your own ISBN, in which case you can appear under your own imprint.

CreateSpace titles apparently are eligible for the SearchInside browsing program (I wonder what the threshhold, or price, for entry is). I assume they will also be open for reader reviews, ratings and such. One thing I’d be very curious to know, however, is whether, or to what extent, CreateSpace titles will get factored into the social filtering and recommendation engines that power Amazon’s browsing experience. In some ways, that would be the best indicator of how much this move will blur the lines – ?in the perceptions of readers – ?between traditional publishing and the new, less authoritative POD channels.

Obviously, this presents a major challenge to other on-demand services like iUniverse, Xlibris and Lulu. It will be interesting to observe how the publishing cultures on these sites will differ. Lulu.com seems to hold the most potential for the emergence of a new ecosystem of independent imprints and publishing storefronts, with the Lulu brand receding into a more infrastructural role. iUniverse and Xlibris still feel more like good old-fashioned vanity presses. Amazon theoretically offers good exposure for self-published authors, but again, as I queried above w/r/t social filtering, will CreateSpace titles be ghetto-ized in an Amazon sub-space or fully integrated into the world of books?

Category Archives: books

welcome siva vaidhyanathan, our first fellow

We are proud to announce that the brilliant media scholar and critic Siva Vaidhyanathan will be establishing a virtual residency here as the Institute’s first fellow. Siva is in the process of moving from NYU to the University of Virginia, where he’ll be teaching media studies and law. While we’re sad to be losing him in New York, we’re thrilled that this new relationship will bring our work into closer, more dynamic proximity. Precisely what “fellowship” entails will develop over time but for now it means that the Institute is the new digital home of SIVACRACY.NET, Siva’s popular weblog. It also means that next month we will be a launching a new website devoted to Siva’s latest book project, The Googlization of Everything, an examination of Google’s disruptive effects on culture, commerce and community.

We are proud to announce that the brilliant media scholar and critic Siva Vaidhyanathan will be establishing a virtual residency here as the Institute’s first fellow. Siva is in the process of moving from NYU to the University of Virginia, where he’ll be teaching media studies and law. While we’re sad to be losing him in New York, we’re thrilled that this new relationship will bring our work into closer, more dynamic proximity. Precisely what “fellowship” entails will develop over time but for now it means that the Institute is the new digital home of SIVACRACY.NET, Siva’s popular weblog. It also means that next month we will be a launching a new website devoted to Siva’s latest book project, The Googlization of Everything, an examination of Google’s disruptive effects on culture, commerce and community.

Siva is one of just a handful of writers to have leveled a consistent and coherent critique of Google’s expansionist policies, arguing not from the usual kneejerk copyright conservatism that has dominated the debate but from a broader cultural and historical perspective: what does it mean for one company to control so much of the world’s knowledge? Siva recently gave a keynote talk at the New Network Theory conference in Amsterdam where he explored some of these ideas, which you can read about here. Clearly Siva’s views on these issues are sympathetic to our own so we’re very glad to be involved in the development of this important book. Stay tuned for more details.

Welcome aboard, Siva.

of shelves and selves

William Drenttel has a lovely post over on Design Observer about the exquisite information of bookshelves, a meditation spurred by 60 photographs of the library of renowned San Francisco designer, typographer, printer and founder of Greenwood Press Jack Stauffacher. Each image (they were taken by Dennis Letbetter) gives a detailed view of one section of Stauffacher’s shelves, a rare glimpse of one individual’s bibliographic DNA, made browseable as a slideshow (unfortunately, the images are not reassembled at the end to give a full view of the collection).

Early evidence suggests that the impulse toward personal mapping through media won’t abate as we go deeper into the digital. Delicious Library and Library Thing are more or less direct transpositions of physical shelves to the computer environment, the latter with an added social dimension (people meeting through their virtual shelves). More generally, social networking sites from Facebook to MySpace are full of self-signification through shelves, or rather lists, of favorite books, movies and music. Social bookmarking sites too bear traces of identity in the websites people save and tag (the tags themselves are a kind of personal signature). Much of the texture and spatial language of the physical may be lost, a new social terrain has opened up, one which we’re only beginning to understand.

But it’s not as though physical bookshelves haven’t always been social. We arrange books not only for our own conceptual orientation, but to give others who venture into our space a sense of our self (or what we’d like to appear as our self), our distinct intellectual algorithm. Browsing a friend’s thoughtfully arranged shelf is like looking through a lens calibrated to their view of the world, especially when those books have played a crucial role, as in Stauffacher’s, in shaping a life’s work. Drenttel savors the idiosyncrasies that inevitably are etched into such a collection:

I have seen many great rare book libraries…. But the libraries I most enjoy are working libraries, where the books have been used and cited and annotated – first editions marred with underlining, notes throughout their pages. (I will always remember the chaos of Susan Sontag’s library, where every book had been touched, read and filled with notes and ephemera.) The organization of a working library is seldom alphabetical…but rather follows some particular mental construct of its owner. Jack Stauffacher’s shelves have some order, one knows. But it is his order, his life.

Or, in Stauffacher’s own words:

Without this working library, I would have no compass, no map, to guide me through the density of our human condition.

six blind men and an elephant

Thomas Mann, author of The Oxford Guide to Library Research, has published an interesting paper (pdf available) examining the shortcomings of search engines and the continued necessity of librarians as guides for scholarly research. It revolves around the case of a graduate student investigating tribute payments and the Peloponnesian War. A Google search turns up nearly 80,000 web pages and 700 books. An overwhelming retrieval with little in the way of conceptual organization and only the crudest of tools for measuring relevance. But, with the help of the LC Catalog and an electronic reference encyclopedia database, Mann manages to guide the student toward a manageable batch of about a dozen highly germane titles.

Summing up the problem, he recalls a charming old fable from India:

Most researchers – at any level, whether undergraduate or professional – who are moving into any new subject area experience the problem of the fabled Six Blind Men of India who were asked to describe an elephant: one grasped a leg and said “the elephant is like a tree”; one felt the side and said “the elephant is like a wall”; one grasped the tail and said “the elephant is like a rope”; and so on with the tusk (“like a spear”), the trunk (“a hose”) and the ear (“a fan”). Each of them discovered something immediately, but none perceived either the existence or the extent of the other important parts – or how they fit together.

Finding “something quickly,” in each case, proved to be seriously misleading to their overall comprehension of the subject.

In a very similar way, Google searching leaves remote scholars, outside the research library, in just the situation of the Blind Men of India: it hides the existence and the extent of relevant sources on most topics (by overlooking many relevant sources to begin with, and also by burying the good sources that it does find within massive and incomprehensible retrievals). It also does nothing to show the interconnections of the important parts (assuming that the important can be distinguished, to begin with, from the unimportant).

Mann believes that books will usually yield the highest quality returns in scholarly research. A search through a well tended library catalog (controlled vocabularies, strong conceptual categorization) will necessarily produce a smaller, and therefore less overwhelming quantity of returns than a search engine (books do not proliferate at the same rate as web pages). And those returns, pound for pound, are more likely to be of relevance to the topic:

Each of these books is substantially about the tribute payments – i.e., these are not just works that happen to have the keywords “tribute” and “Peloponnesian” somewhere near each other, as in the Google retrieval. They are essentially whole books on the desired topic, because cataloging works on the assumption of “scope-match” coverage – that is, the assigned LC headings strive to indicate the contents of the book as a whole….In focusing on these books immediately, there is no need to wade through hundreds of irrelevant sources that simply mention the desired keywords in passing, or in undesired contexts. The works retrieved under the LC subject heading are thus structural parts of “the elephant” – not insignificant toenails or individual hairs.

If nothing else, this is a good illustration of how libraries, if used properly, can still be much more powerful than search engines. But it’s also interesting as a librarian’s perspective on what makes the book uniquely suited for advanced research. That is: a book is substantial enough to be a “structural part” of a body of knowledge. This idea of “whole books” as rungs on a ladder toward knowing something. Books are a kind of conceptual architecture that, until recently, has been distinctly absent on the Web (though from the beginning certain people and services have endeavored to organize the Web meaningfully). Mann’s study captures the anxiety felt at the prospect of the book’s decline (the great coming blindness), and also the librarian’s understandable dread at having to totally reorganize his/her way of organizing things.

It’s possible, however, to agree with the diagnosis and not the prescription. True, librarians have gotten very good at organizing books over time, but that’s not necessarily how scholarship will be produced in the future. David Weinberg ponders this:

As an argument for maintaining human expertise in manually assembling information into meaningful relationships, this paper is convincing. But it rests on supposing that books will continue to be the locus of worthwhile scholarly information. Suppose more and more scholars move onto the Web and do their thinking in public, in conversation with other scholars? Suppose the Web enables scholarship to outstrip the librarians? Manual assemblages of knowledge would retain their value, but they would no longer provide the authoritative guide. Then we will have either of two results: We will have to rely on “‘lowest common denominator'”and ‘one search box/one size fits all’ searching that positively undermines the requirements of scholarly research”…or we will have to innovate to address the distinct needs of scholars….My money is on the latter.

As I think is mine. Although I would not rule out the possibility of scholars actually participating in the manual assemblage of knowledge. Communities like MediaCommons could to some extent become their own libraries, vetting and tagging a wide array of electronic resources, developing their own customized search frameworks.

There’s much more in this paper than I’ve discussed, including a lengthy treatment of folksonomies (Mann sees them as a valuable supplement but not a substitute for controlled taxonomies). Generally speaking, his articulation of the big challenges facing scholarly search and librarianship in the digital age are well worth the read, although I would argue with some of the conclusions.

the paper e-book

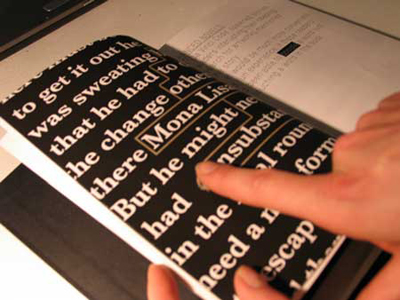

Manolis Kelaidis, a designer at the Royal College of Art in London, has found a way to make printed pages digitally interactive. His “blueBook” prototype is a paper book with circuits embedded in each page and with text printed with conductive ink. When you touch a “linked” word on the page and your finger completes a circuit, sending a signal to a processor in the back cover which communicates by Bluetooth with a nearby computer, bringing up information on the screen.

(image from booktwo.org)

I’ve heard from a number of people that Kelaidis brought down the house last week at O’Reilly’s “Tools of Change for Publishing” conference in San Jose. Andrea Laue, who blogs at jusTaText, did a nice write-up:

He asked the audience if, upon encountering an obscure reference or foreign word on the page of a book, we would appreciate the option of touching the word on the page and being taken (on our PC) to an online resource that would identify or define the unfamiliar word. Then he made it happen. Standing O.

Yes, he had a printed and bound book which communicated with his laptop. He simply touched the page, and the laptop reacted. It brought up pictures of the Mona Lisa. It translated Chinese. It played a piece of music. Kelaidis suggested that a library of such books might cross-refer, i.e. touching a section in one book might change the colors of the spines of related books on your shelves. Imagine.

So there you have it. A networked book – in print. Amazing.

It’s not surprising to hear that the O’Reilly crowd, filled with anxious publishers, was ecstatic about the blueBook. Here was tangible proof that print can be meaningfully integrated with the digital world without sacrificing its essential formal qualities: the love child of the printed book and the companion CD-ROM. And since so much of the worry in publishing is really about the crumbling of business models and only secondarily about the essential nature of books or publishing, it was no doubt reassuring to imagine something like the blueBook as the digital book of the future: a physical object that can be reliably bought and sold (and which, with all those conductors, circuits and processors involved, would be exceedingly difficult to copy).

Kelaidis’ invention definitely sounds wonderful, but is it a plausible vision of things to come? I suppose electronic paper of all kinds, pulp and polymer, will inevitably get better and cheaper over time. How transient and historically contingent is our attachment to paper? There’s a compelling argument to be made (Gary Frost makes it, and we frequently debate it around the table here) that, in spite of all the new possibilities opened up by digital technologies, the paper book is a unique ergonomic fit for the human hand and mind, and, moreover, that its “bounded” nature allows for a kind of reading that people will want to keep distinct from the more fragmentary and multi-directional forms of reading we do on computers and online. (That’s certainly my personal reading strategy these days.) Perhaps, with something like the blueBook, it would be possible to have the best of both worlds.

But what about accessibility? What about trees? By the time e-paper is a practical reality, will attachment to print have definitively ebbed? Will we be used to a greater degree of interactivity (the ability not only to link text but to copy, edit and recombine it, and to mix it directly, on the “page,” with other media) than even the blueBook can provide?

Subsequent thought:A discussion about this on an email list I subscribe to reminded me of the intellectual traps that I and many others fall into when speculating about future technologies: the horse race (which technology will win?), the either/or question. What do I really think? The future of the book is not monolithic but rather a multiplicity of things – the futures of the book – and I expect (and hope) that well-crafted hyrbrid works like Kelaidis’ will be among those futures./thought

We just found out that next week Kelaidis will be spending a full day at the Institute so we’ll be able to sift through some of these questions in person.

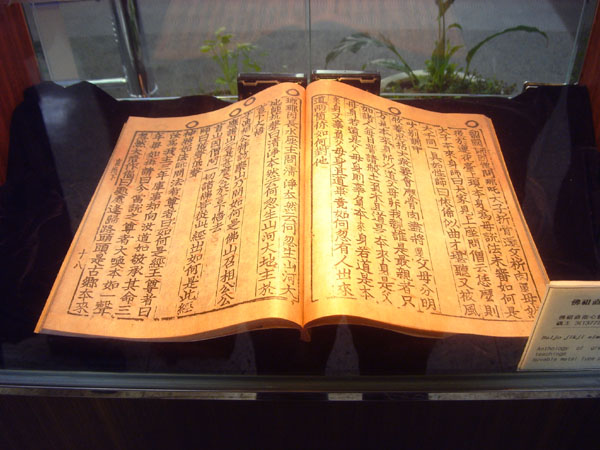

johannes who?

This is the oldest existing document in the world printed with metal movable type: an anthology of Zen teachings, Goryeo Dynasty, Korea… 1377. It’s a little known fact, at least in the West, that movable type was first developed in Korea circa 1230, over 200 years before that goldsmith from Mainz came on the scene. I saw this today in the National Library of Korea in Seoul (more on that soon). This book is actually a reproduction. The original resides in Paris and is the subject of a bitter dispute between the French and Korean governments.

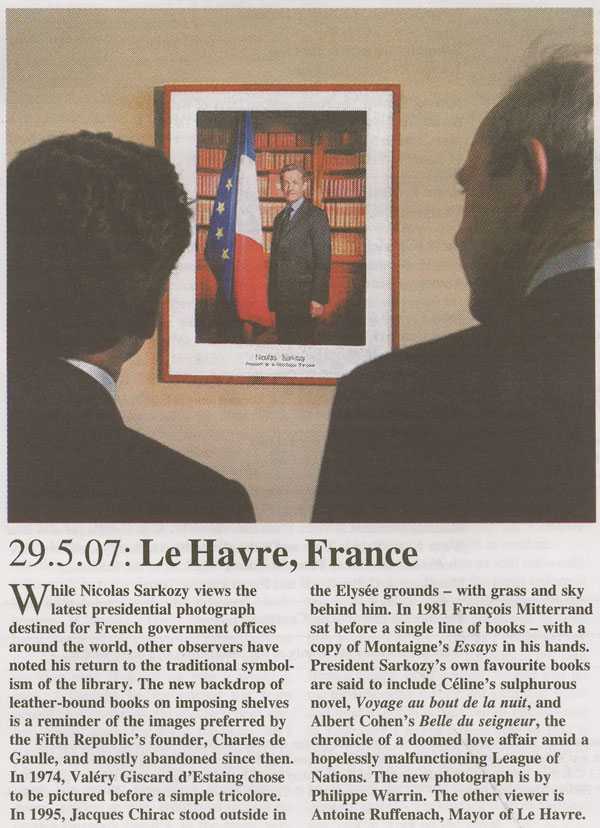

the authority of books

(from p. 3 of the June 15, 2007 edition of the Times Literary Supplement.)

chapters à la carte

O’Reilly is now offering 714 of its titles with an option to purchase individual chapters: PDFs for $3.99 a pop.

Seems an occasion to revisit this post: “Dismantling the Book.”

(Thanks, Peter Brantley, for the link.)

the institute on the millions

There is a piece about the Institute on the book/literary blog the millions, by Buzz Poole, a writer who came down to visit us for a long afternoon late last summer. Buzz takes solid a crack at describing what we do and why. He starts out by briefly sketching out the increasingly unstable ground that defines contemporary publishing, and nails one of the major problems we often lament here:

In the realm of publishing, however, especially mainstream publishing, the concerns and campaigns are geared to getting better at selling books, not to how the very nature of books is, and has been, changing for years.

Poole then describes the Institute and the intellectual and material history that we come out of, namely Voyager and similar interactive multimedia development. But then he says something that I think is really on point about us and our work:

The most influential people behind the Institute are not so much about the technology; rather they are about intellectual economies where theory and practice are equally valued. The Institute wants to do more than democratize information; it wants to reappraise the exchange of information and how it is valued.

The next section is all about our projects, our forays into the intellectual economies and our attempts to participate in the wide world of the web. (You can get a sense of our projects on our site). Poole closes with a discussion of what his text would be like if the Institute conceived of the format: how it would include reading lists and links (and probably full texts, if we really could have our way), examples of media, drafts/versioning, and the ability to interact with the author. What he doesn’t say is that this piece was originally being pitched as a magazine article, which fortuitously landed on a blog instead. We like being written up in paper, but even the most common digital form allows for a much wider range of instantaneous interaction and investigation. The fact that this piece is on a blog—and not an expanded (expandable?) format—is a testament to how much further the tools and practices of writing still need to advance before we begin to approach our vision of ‘networked book’.

cache me if you can

Over at Teleread, David Rothman has a pair of posts about Google’s new desktop RSS reader and a couple of new technologies for creating “offline web applications” (Google Gears and Adobe Apollo), tying them all together into an interesting speculation about the possibility of offline networked books. This would mean media-rich, hypertextual books that could cache some or all of their remote elements and be experienced whole (or close to whole) without a network connection, leveraging the local power of the desktop. Sophie already does this to a limited degree, caching remote movies for a brief period after unplugging.

Electronic reading is usually prey to a million distractions and digressions, but David’s idea suggests an interesting alternative: you take a chunk of the network offline with you for a more sustained, “bounded” engagement. We already do this with desktop email clients and RSS readers, which allow us to browse networked content offline. This could be expanded into a whole new way of reading (and writing) networked books. Having your own copy of a networked document. Seems this should be a basic requirement for any dedicated e-reader worth its salt, to be able to run rich web applications with an “offline” option.