Observe these gorgeous Rorshach mold blots blooming their way across the pages of old books. A video by Ben Hemmendinger, found on Vimeo.

The piece is titled “Edelfäule,” which a little Googling reveals to be German for “noble rot” -? “referring to BOTRYTIS CINEREA, the beneficial mold responsible for the TROCKENBEERENAUSLESE wines.” (Epicurious Wine Dictionary).

Thanks Alex for the link!

Category Archives: books

penguin enlists amazon reviewers to sift fiction slush pile

In an interesting mashup of online social filtering and old-fashioned publishing, Penguin, Amazon and Hewlett Packard have joined forces to present a new online literary contest, the Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award. From the NY Times:

From today through Nov. 5, contestants from 20 countries can submit unpublished manuscripts of English-language novels to Amazon, which will assign a small group of its top-rated online reviewers to evaluate 5,000-word excerpts and narrow the field to 1,000. The full manuscripts of those semifinalists will be submitted to Publishers Weekly, which will assign reviewers to each. Amazon will post the reviews, along with excerpts, online, where customers can make comments. Using those comments and the magazine’s reviews, Penguin will winnow the field to 100 finalists who will get two readings by Penguin editors. When a final 10 manuscripts are selected, a panel including Elizabeth Gilbert, the author of the current nonfiction paperback best seller “Eat, Pray, Love,” and John Freeman, the president of the National Book Critics Circle, will read and post comments on the novels at Amazon. Readers can then vote on the winner, who will receive a publishing contract and a $25,000 advance from Penguin.

eeeeeeeeeee…..eeeeeeee…eeeee

Moby Dick Chapter 55 or 9200 times E”, 2004, graphite on hemp paper, 11 x 9″

In one of those odd, blogospheric delayed reactions, I just came across (via Information Aesthetics, via Kottke) a fabulous exhibit that took place this past March by an artist named Justin Quinn, who does beautiful, mysterious work with text. Quinn’s Moby-Dick series is made up of obsessively detailed prints and graphite drawings composed entirely of the letter E. Each E corresponds to a letter in a chapter of Melville’s book, so each piece is composed of literally thousands of characters. The effect is almost that of a mosaic or a concrete poem. This series was shown at MMGalleries in San Francisco and has since moved elsewhere (Miami possibly?), but there are still a number of images online (also here). Quinn explains his obsession with E:

The distance between reading and seeing has been an ongoing interest for me. Since 1998 I have been exploring this space through the use of letterforms, and have used the letter E as my primary starting point for the last two years. Since E is often found at the top of vision charts, I questioned what I saw as a familiar hierarchy. Was this letter more important than other letters? E is, after all, the most commonly used letter in the English language, it denotes a natural number (2.71828), and has a visual presence that interests me greatly. In my research E has become a surrogate for all letters in the alphabet. It now replaces the other letters and becomes a universal letter (or Letter), and a string of Es now becomes a generic language (or Language). This substitution denies written words their use as legible signifiers, allowing language to become a vacant parallel Language -? a basis for visual manufacture.

After months of compiling Es into abstract compositions through various systemic arrangements, I started recognizing my studio time as a quasi-monastic experience. There was something sublime about both the compositions that I was making and the solitude in which they were made. It was as if I were translating some great text like a subliterate medieval scribe would have years ago – ?with no direct understanding of the source material. The next logical step was to find a source. Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick, a story rich in theology, philosophy, and psychosis provides me with a roadmap for my work, but also with a series of underlying narratives. My drawings, prints, and collages continue to speak of language and the transferal of information, but now as a conduit to Melville’s sublime narratives.

Gazing at these for a while (digital reproductions of course… and on my browser… and brought to my attention through technology blogs), I couldn’t help but start to draw some connections between Quinn’s work and computers. There’s plenty of digital artwork and visualization programs that render text into complex visual formations, sometimes with the intention of discovering new meanings and relationships, other times purely to play with form. Every now and then, someone manages to achieve both. This is a detail from Brad Paley’s rendering of Gamer Theory through his program Text Arc:

Others can be beautiful to handle, but are ultimately opaque, like Ben Fry’s “Valence”:

These two images are from another work submitted to our Gamer Theory visualization gallery, a map of nouns and verbs in Wark’s text (first is full, second is a detail). It’s pretty, but basically meaningless.

Quinn’s work is also difficult to penetrate, but something about it holds my attention. I’m not sure how aware Quinn is of the digital work being done today, but viewing his pieces against the contemporary technological backdrop, and his own self-described feeling of being the “subliterate medieval scribe” as he makes his minute articulations, my mind runs off in a number of directions. Seeing that his work is in a way “pixelated” – ?his Es a “basis for visual manufacture” – ?I imagine him as a sort of human computer – ?a monastic machine – ?processing (or intuiting) the text by infintessimal degrees through his own inner algorithm.

After all, a computer’s work is “subliterate.” Algorithms must be designed with intelligence, but the actual running of the program is physical, mindless. Viewed this way, Quinn’s work is like a dive into the mania of operations usually carried out with blazing speed by microprocessors. This is not to diminish it, or to call it cold and mechanical. Rather I’m pondering whether there is perhaps a spiritual dimension to the repetitive, sub-rational activities of our machines, which, if transposed to human scale, can become a sort of devotional exercise, like the routines of Buddhist monks, endlessly painting and carving Chinese characters in order to empty their minds (other links between monks and computers here and here).

What’s particularly evocative to me about the work, however, is how it treads the line between that meditative quality and the obsessive. There is something frightening about them (or about any kind of fanatically detailed artwork, or about computers for that matter), like the reams of psychotic babble typed out ceaselessly by Jack Nicholson in “The Shining.” Or is it Ahab’s vengeance algorithm we’re seeing, running on overdrive until the machine (or ship) crashes?

In the end, Quinn’s images are mysterious, his algorithm inscrutable, although my mind immediately goes to work trying to link up Melville’s themes and images to those endless strings of Es.

Here’s that first image again with a quote from the source text that seemed to me to connect. Chapter 55, “Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales”:

Moby Dick Chapter 55 or 9200 times E”, 2004, graphite on hemp paper, 11 x 9″

But these manifold mistakes in depicting the whale are not so very surprising after all. Consider! Most of the scientific drawings have been taken from the stranded fish; and these are about as correct as a drawing of a wrecked ship, with broken back, would correctly represent the noble animal itself in all its undashed pride of hull and spars. Though elephants have stood for their full-lengths, the living Leviathan has never yet fairly floated himself for his portrait. The living whale, in his full majesty and significance, is only to be seen at sea in unfathomable waters; and afloat the vast bulk of him is out of sight, like a launched line-of-battle ship; and out of that element it is a thing eternally impossible for mortal man to hoist him bodily into the air, so as to preserve all his mighty swells and undulations.

This one is of chapter 71, “The Jeroboam’s Story” (I spoke briefly on the phone with one of the curators who told me that Quinn had explained this as an inverted halo, reflecting the anti-Christ-like character described in the chapter – ?I almost see an aerial view of a whale cutting through water):

Moby Dick Chapter 71 or 9,814 times E”, 2006, mixed media, 11 x 15″

…but straightway upon the ship’s getting out of sight of land, his insanity broke out in a freshet. He announced himself as the archangel Gabriel, and commanded the captain to jump overboard. He published his manifesto, whereby he set himself forth as the deliverer of the isles of the sea and vicar-general of all Oceanica. The unflinching earnestness with which he declared these things; – the dark, daring play of his sleepless, excited imagination, and all the preternatural terrors of real delirium, united to invest this Gabriel in the minds of the majority of the ignorant crew, with an atmosphere of sacredness. Moreover, they were afraid of him. As such a man, however, was not of much practical use in the ship, especially as he refused to work except when he pleased, the incredulous captain would fain have been rid of him; but apprised that that individual’s intention was to land him in the first convenient port, the archangel forthwith opened all his seals and vials – devoting the ship and all hands to unconditional perdition, in case this intention was carried out. So strongly did he work upon his disciples among the crew, that at last in a body they went to the captain and told him if Gabriel was sent from the ship, not a man of them would remain.

the googlization of everything: a public writing begins

We’re very excited to announce that Siva’s new Google book site, produced and hosted by the Institute, is now live! In addition to being the seed of what will likely be a very important book, I’ll bet that over time this will become one of the best Google-focused blogs on the Web.

The Googlization of Everything: How One Company is Disrupting Culture, Commerce, and Community… and Why We Should Worry.

The book:

…a critical interpretation of the actions and intentions behind the cultural behemoth that is Google, Inc. The book will answer three key questions: What does the world look like through the lens of Google?; How is Google’s ubiquity affecting the production and dissemination of knowledge?; and how has the corporation altered the rules and practices that govern other companies, institutions, and states?

I have never tried to write a book this way. Few have. Writing has been a lonely, selfish pursuit for my so far. I tend to wall myself off from the world (and my loved ones) for days at a time in fits and spurts when I get into a writing groove. I don’t shave. I order pizza. I grumble. I ignore emails from my mother.

I tend to comb through and revise every sentence five or six times (although I am not sure that actually shows up in the quality of my prose). Only when I am sure that I have not embarrassed myself (or when the editor calls to threaten me with a cancelled contract – whichever comes first) do I show anyone what I have written. Now, this is not an uncommon process. Closed composition is the default among writers. We go to great lengths to develop trusted networks of readers and other writers with whom we can workshop – or as I prefer to call it because it’s what the jazz musicians do, woodshed our work.

Well, I am going to do my best to woodshed in public. As I compose bits and pieces of work, I will post them here. They might be very brief bits. They might never make it into the manuscript. But they will be up here for you to rip up or smooth over.

That’s the thing. For a number of years now I have made my bones in the intellectual world trumpeting the virtues of openness and the values of connectivity. I was an early proponent of applying “open source” models to scholarship, journalism, and lots of other things.

And, more to the point: One of my key concerns with Google is that it is a black box. Something that means so much to us reveals so little of itself.

So I would be a hypocrite if I wrote this book any other way. This book will not be a black box.

from booktrust to books of the future

I’m delighted to be joining the team at the Institute. I’m not an academic but a deviser and manager of projects to promote creative reading, so thinking and doing go together for me. As Director of Booktrust for seven years and of the Poetry Society before that, I’ve been particularly interested in finding new ways to bring readers and writers together. At the Poetry Society we ran a scheme that put poets to work in community settings, opening up access to their work but also providing each writer with new networks of communication, communities of readers and sources of inspiration. Booktrust runs the amazing Bookstart scheme which gives books to babies and small children, seeding a love of words and pictures before literacy blooms. The web has become a vital tool in promoting all kinds of reading and one Booktrust site well worth exploring is STORY, the campaign to keep short fiction alive and thriving; it’s an ideal form to read online.

But I’ve been struck recently by how so much reading promotion cuts literature off from other media, as if anyone still lives solely in a ‘world of books’. We all exist in a multiculture now, and there’s a need to look much harder at how we connect ideas gleaned from tv, websites, books and real life conversations to patch together our personal stances and narratives.

Conventional publishers and their authors wonder how they’ll survive as industries converge and users generate. Working with if:book I’m keen to look hard at different means to bring quality writing – and in particular fiction – to new audiences, so that writers can afford to eat and readers can savour genuinely compelling writing on-line.

When I’ve told colleagues about my move from Booktrust to exploring the future of the book, I’ve had howls of outrage and alarm from some unexpected sources. People who spend their days at a computer and evenings watching TV screens are horrified that I might be out to deprive them of the pleasure of their paperbacks. Readers cling on tight to their tomes as if literature and stationary were inseparable; meanwhile the digital world has stretched the definition of book to include laptops and social networks. So in the era of MacBooks and FaceBook, what does the (paper)book represent to people? It’s a constant in the flux of change; something worth concentrating on and keeping afterwards. Of course plenty of fiction and non-fiction published is transient crap, but research shows that people find it hard to throw away a piece of print if it’s perfect bound.

So a future book should be using all the opportunities that new media affords, but without breathlessness. The kind of pointless interactivity that the BBC’s Jeremy Paxman complained about at this year’s Edinburgh TV Festival really isn’t good enough. Whether we consume it via an e-reader, a mobile, laptop or a document printed on demand, a future book will need to be worth sticking with, the product of some serious thought and time, a carefully constructed whole. It will be rendered using the extended palette of multimedia possibilities open to makers, may be a team effort or the work of a solo author, may incorporate space for reader response and links to other sites, may use a range of delivery methods, be porous and evolving, but if it doesn’t have the integrity and quality we expect from literature then something far more important than the nostalgic musty smell of old paperbacks will have been lost.

Where do literature and stories fit in our lives? That’s the question I’ve always been most interested in. The answer changes all the time, and that’s why the work of the Institute for the Future of the Book seems to me so important.

altered states

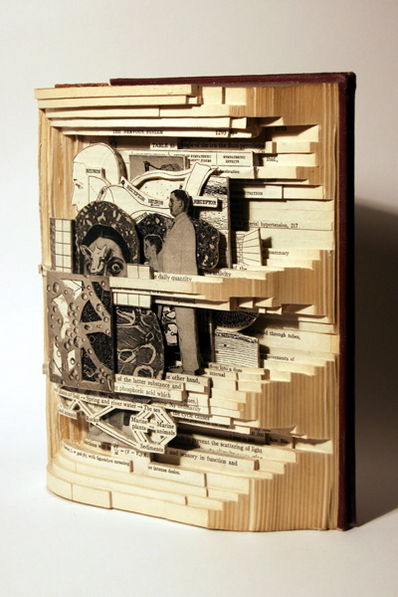

“The Physiological Basis of Medical Practice, 2006”, Altered book, 9 x 7-1/2 x 3-1/4 inches.

By Brian Dettmer at Haydee Rovirosa Gallery, New York.

(via Ron Silliman)

shock treatment

I’ve never been a fan of book trailers, but this disturbing six-minute agitprop piece promoting Naomi Klein’s new book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism is genre-transcending. It doesn’t hurt that Klein teamed up with Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón, who made what was for my money the best major release picture of last year, “Children of Men.” Here, Klein and Cuarón are co-writers, Cuarón’s son Jonás directs and edits, and Klein provides narration over a melange of chilling footage and animation that sets up her central thesis and metaphor: that free market capitalist reforms are generally advanced, undemocratically, through breaches in the social psyche created by political, economic, environmental or military shocks. It’s a shocking little video. Make you wanna read the book?

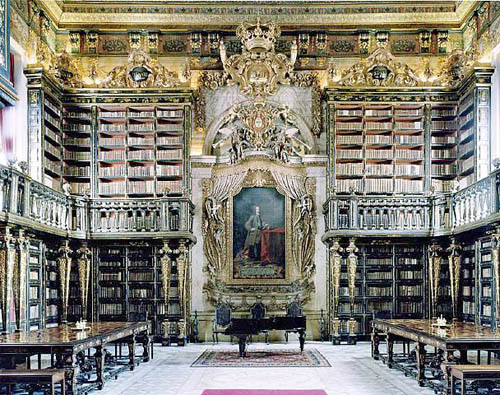

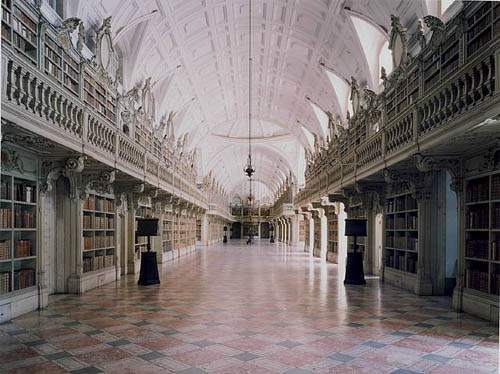

candida höfer: the library as museum

The photographs of libraries in “Portugal,” the current exhibition of Candida Höfer at Sonnabend, show libraries as venerable places where precious objects are stored.

The large format that characterizes Höfer’s photographs of public places, the absence of people, and the angle from which she composes them, invite the viewer “to enter” the rooms and observe. Photography is a silent medium and in Höfer’s libraries this is magnified, creating that feeling of “temple of learning” with which libraries have often been identified. On the other hand, the meticulous attention to detail, hand-painted porcelain markers, ornately carved bookcases, murals, stained glass windows, gilt moldings, and precious tomes are an eloquent representation of libraries as palaces of learning for the privileged. In spite of that, and ever since libraries became public spaces, anyone, in theory, has access to books and the concept of gain or monetary value rarely enters the user’s mind.

Libraries are a book lover’s paradise, a physical compilation of human knowledge in all its labyrinthine intricacy. With digitization, libraries gain storage capacity and readers gain accessibility, but they lose both silence and awe. Even though in the digital context, the basic concept of the library as a place for the preservation of memory remains, for many “enlightened” readers the realization that human memory and knowledge are handled by for-profit enterprises such as Google, produces a feeling of merchants in the temple, a sense that the public interest has fallen, one more time, into private hands.

As we well know, the truly interesting development in the shift from print to digital is the networked environment and its effects on reading and writing. If, as Umberto Eco says, books “are machines that provoke further thoughts” then the born-digital book is a step toward the open text, and the “library” that eventually will hold it, a bird of different feather.

e-book developments at amazon, google (and rambly thoughts thereon)

The NY Times reported yesterday that the Kindle, Amazon’s much speculated-about e-book reading device, is due out next month. No one’s seen it yet and Amazon has been tight-lipped about specs, but it presumably has an e-ink screen, a small keyboard and scroll wheel, and most significantly, wireless connectivity. This of course means that Amazon will have a direct pipeline between its store and its device, giving readers access an electronic library (and the Web) while on the go. If they’d just come down a bit on the price (the Times says it’ll run between four and five hundred bucks), I can actually see this gaining more traction than past e-book devices, though I’m still not convinced by the idea of a dedicated book reader, especially when smart phones are edging ever closer toward being a credible reading environment. A big part of the problem with e-readers to date has been the missing internet connection and the lack of a good store. The wireless capability of the Kindle, coupled with a greater range of digital titles (not to mention news and blog feeds and other Web content) and the sophisticated browsing mechanisms of the Amazon library could add up to the first more-than-abortive entry into the e-book business. But it still strikes me as transitional – ?a red herring in the larger plot.

A big minus is that the Kindle uses a proprietary file format (based on Mobipocket), meaning that readers get locked into the Amazon system, much as iPod users got shackled to iTunes (before they started moving away from DRM). Of course this means that folks who bought the cheaper (and from what I can tell, inferior) Sony Reader won’t be able to read Amazon e-books.

But blech… enough about ebook readers. The Times also reports (though does little to differentiate between the two rather dissimilar bits of news) on Google’s plans to begin selling full online access to certain titles in Book Search. Works scanned from library collections, still the bone of contention in two major lawsuits, won’t be included here. Only titles formally sanctioned through publisher deals. The implications here are rather different from the Amazon news since Google has no disclosed plans for developing its own reading hardware. The online access model seems to be geared more as a reference and research tool -? a powerful supplement to print reading.

But project forward a few years… this could develop into a huge money-maker for Google: paid access (licensed through publishers) not only on a per-title basis, but to the whole collection – ?all the world’s books. Royalties could be distributed from subscription revenues in proportion to access. Each time a book is opened, a penny could drop in the cup of that publisher or author. By then a good reading device will almost certainly exist (more likely a next generation iPhone than a Kindle) and people may actually be reading books through this system, directly on the network. Google and Amazon will then in effect be the digital infrastructure for the publishing industry, perhaps even taking on what remains of the print market through on-demand services purveyed through their digital stores. What will publishers then be? Disembodied imprints, free-floating editorial organs, publicity directors…?

Recent attempts to develop their identities online through their own websites seem hopelessly misguided. A publisher’s website is like their office building. Unless you have some direct stake in the industry, there’s little reason to bother know where it is. Readers are interested in books not publishers. They go to a bookseller, on foot or online, and they certainly don’t browse by publisher. Who really pays attention to who publishes the books they read anyway, especially in this corporatized era where the difference between imprints is increasingly cosmetic, like the range of brands, from dish soap to potato chips, under Proctor & Gamble’s aegis? The digital storefront model needs serious rethinking.

The future of distribution channels (Googlezon) is ultimately less interesting than this last question of identity. How will today’s publishers establish and maintain their authority as filterers and curators of the electronic word? Will they learn how to develop and nurture literate communities on the social Web? Will they be able to carry their distinguished imprints into a new terrain that operates under entirely different rules? So far, the legacy publishers have proved unable to grasp the way these things work in the new network culture and in the long run this could mean their downfall as nascent online communities (blog networks, webzines, political groups, activist networks, research portals, social media sites, list-servers, libraries, art collectives) emerge as the new imprints: publishing, filtering and linking in various forms and time signatures (books being only one) to highly activated, focused readerships.

The prospect of atomization here (a million publishing tribes and sub-tribes) is no doubt troubling, but the thought of renewed diversity in publishing after decades of shrinking horizons through corporate consolidation is just as, if not more, exciting. But the question of a mass audience does linger, and perhaps this is how certain of today’s publishers will survive, as the purveyors of mass market fare. But with digital distribution and print on demand, the economies of scale rationale for big publishers’ existence takes a big hit, and with self-publishing services like Amazon CreateSpace and Lulu.com, and the emergence of more accessible authoring tools like Sophie (still a ways away, but coming along), traditional publishers’ services (designing, packaging, distributing) are suddenly less special. What will really be important in a chaotic jumble of niche publishers are the critics, filterers and the context-generating communities that reliably draw attention to the things of value and link them meaningfully to the rest of the network. These can be big companies or light-weight garage operations that work on the back of third-party infrastructure like Google, Amazon, YouTube or whatever else. These will be the new publishers, or perhaps its more accurate to say, since publishing is now so trivial an act, the new editors.

Of course social filtering and tastemaking is what’s been happening on the Web for years, but over time it could actually supplant the publishing establishment as we currently know it, and not just the distribution channels, but the real heart of things: the imprimaturs, the filtering, the building of community. And I would guess that even as the digital business models sort themselves out (and it’s worth keeping an eye on interesting experiments like Content Syndicate, covered here yesterday, and on subscription and ad-based models), that there will be a great deal of free content flying around, publishers having finally come to realize (or having gone extinct with their old conceits) that controlling content is a lost cause and out of synch with the way info naturally circulates on the net. Increasingly it will be the filtering, curating, archiving, linking, commenting and community-building -? in other words, the network around the content -? that will be the thing of value. Expect Amazon and Google (Google, btw, having recently rolled out a bunch of impressive new social tools for Book Search, about which more soon) to move into this area in a big way.

“the bookish character of books”: how google’s romanticism falls short

Check out, if you haven’t already, Paul Duguid’s witty and incisive exposé of the pitfalls of searching for Tristram Shandy in Google Book Search, an exercise which puts many of the inadequacies of the world’s leading digitization program into relief. By Duguid’s own admission, Lawrence Sterne’s legendary experimental novel is an idiosyncratic choice, but its many typographic and structural oddities make it a particularly useful lens through which to examine the challenges of migrating books successfully to the digital domain. This follows a similar examination Duguid carried out last year with the same text in Project Gutenberg, an experience which he said revealed the limitations of peer production in generating high quality digital editions (also see Dan’s own take on this in an older if:book post). This study focuses on the problems of inheritance as a mode of quality assurance, in this case the bequeathing of large authoritative collections by elite institutions to the Google digitization enterprise. Does simply digitizing these – ?books, imprimaturs and all – ?automatically result in an authoritative bibliographic resource?

Duguid’s suggests not. The process of migrating analog works to the digital environment in a way that respects the orginals but fully integrates them into the networked world is trickier than simply scanning and dumping into a database. The Shandy study shows in detail how Google’s ambition to organizing the world’s books and making them universally accessible and useful (to slightly adapt Google’s mission statement) is being carried out in a hasty, slipshod manner, leading to a serious deficit in quality in what could eventually become, for better or worse, the world’s library. Duguid is hardly the first to point this out, but the intense focus of his case study is valuable and serves as a useful counterpoint to the technoromantic visions of Google boosters such as Kevin Kelly, who predict a new electronic book culture liberated by search engines in which readers are free to find, remix and recombine texts in various ways. While this networked bibliotopia sounds attractive, it’s conceived primarily from the standpoint of technology and not well grounded in the particulars of books. What works as snappy Web2.0 buzz doesn’t necessarily hold up in practice.

As is so often the case, the devil is in the details, and it is precisely the details that Google seems to have overlooked, or rather sprinted past. Sloppy scanning and the blithe discarding of organizational and metadata schemes meticulously devised through centuries of librarianship, might indeed make the books “universally accessible” (or close to that) but the “and useful” part of the equation could go unrealized. As we build the future, it’s worth pondering what parts of the past we want to hold on to. It’s going to have to be a slower and more painstaking a process than Google (and, ironically, the partner libraries who have rushed headlong into these deals) might be prepared to undertake. Duguid:

The Google Books Project is no doubt an important, in many ways invaluable, project. It is also, on the brief evidence given here, a highly problematic one. Relying on the power of its search tools, Google has ignored elemental metadata, such as volume numbers. The quality of its scanning (and so we may presume its searching) is at times completely inadequate. The editions offered (by search or by sale) are, at best, regrettable. Curiously, this suggests to me that it may be Google’s technicians, and not librarians, who are the great romanticisers of the book. Google Books takes books as a storehouse of wisdom to be opened up with new tools. They fail to see what librarians know: books can be obtuse, obdurate, even obnoxious things. As a group, they don’t submit equally to a standard shelf, a standard scanner, or a standard ontology. Nor are their constraints overcome by scraping the text and developing search algorithms. Such strategies can undoubtedly be helpful, but in trying to do away with fairly simple constraints (like volumes), these strategies underestimate how a book’s rigidities are often simultaneously resources deeply implicated in the ways in which authors and publishers sought to create the content, meaning, and significance that Google now seeks to liberate. Even with some of the best search and scanning technology in the world behind you, it is unwise to ignore the bookish character of books. More generally, transferring any complex communicative artifacts between generations of technology is always likely to be more problematic than automatic.

Also take a look at Peter Brantley’s thoughts on Duguid:

Ultimately, whether or not Google Book Search is a useful tool will hinge in no small part on the ability of its engineers to provoke among themselves a more thorough, and less alchemic, appreciation for the materials they are attempting to transmute from paper to gold.