Circulating briskly last week around the blogosphere was an interesting trio of posts (part 1, part 2, part 3) by the thriller writer Barry Eisler pondering how various roles in the present-day publishing ecosystem might evolve – ?or go extinct – ?in the coming decades. He envisions a world (an America at least) where mega-chains and big box retailers have taken over most of the distribution functions of publishers. Each store powers a squadron of on-demand printers (like the Espresso Book Machine), churning out paperbacks from a limitless digital backlist – ?think of a Kinkos and a Starbucks fused together with a small browsing area in between. Direct dealings with authors, including editing, copyediting and packaging, have largely become the work of agents, who broker distribution with various on and offline retailers. Authors themselves have become the brands. In some cases retailers ink deals to run exclusive authorial product lines – ?like Tom Clancy’s “Op Center” or James Patterson’s various co-authored spinoffs – ?in their stores. Lesser known writers can make a living writing for these franchises, riding the coattails of tomorrow’s Dan Browns and Sue Graftons.

In a flat distribution world, retailers will need publishers less, perhaps, eventually, not at all (or rather, retailers will become publishers themselves). But they’ll still need someone to help them cut through the clutter. And someone will still need to represent authors to buyers. I expect agents will start selling directly to retailers, and that their business won’t be nearly as affected by flattening distribution as will publishers’.

Eisler is really talking primarily about blockbusters here, and within that limited scope his predictions seem sound (though I think he seriously underestimates the extent to which reading will go entirely digital). Authors in the “short head” of the curve are already essentially brands and it’s only a matter of time before they realize that their publishers’ services are no longer required and that they can keep a much bigger cut of the proceeds by going it alone. Eisler points to the situation in the music biz and Madonna and Radiohead – ?superstars who bucked their record labels in favor of independent distribution and have been wildly successful. But what does this prove? Blockbuster acts with legacy brands and massive fanbases can easily establish their own media empires – ?Stephen King toyed with the idea with his 2000 serial e-novel The Plant, which he sold directly to readers with modest success.

The point is that these examples shed little light on the future except for those few who are already at the top of the heap – ?that tiny heap which has become so disproportionately favored by an over-consolidated, bottom line-driven industry. Rather than heralding a new age of self-determination by artists, the Madonnas and Stephen Kings are the exceptions that prove the rule that, while distribution may have been radically flattened by the net, attention and audience are as hard (if not harder) to come by as ever. How the vast majority of writers will make a living, and how they might have to adapt their craft to do so, is far less clear (the R.U. Sirius piece I linked to earlier this month, which interviews ten serious midlist writers who have done a fairly good job of setting up online, “branded,” presences, is a good barometer of current anxieties).

Eisler’s right, though, that publishers need to start thinking hard about what they have to offer beyond distribution or else go the way of the dodo. But it won’t just be the agents that replace them but a melange of evolved Web impresarios: bloggers, curators, list-server editors, social bookmarkers and other online tastemakers. But writers too will have to change to survive. The digital medium will provide more maneuverability and more potential reach, but less shelter and less of the hand-holding, buffering and insulation from their public that publishers traditionally provided when once upon a time they managed the production and distribution chain. In many cases, writers will have to work harder at being impresarios, developing public personae and maintaining a more direct communication with readers. They’ll have to learn how to write all over again.

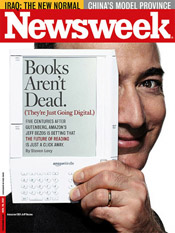

Steven Levy’s Newsweek cover story, “The Future of Reading,” is pegged to the much anticipated release of the Kindle, Amazon’s new e-book reader. While covering a lot of ground, from publishing industry anxieties, to mass digitization, Google, and speculations on longer-term changes to the nature of reading and writing (including a few remarks from us), the bulk of the article is spent pondering the implications of this latest entrant to the charred battlefield of ill-conceived gadgetry which has tried and failed for more than a decade to beat the paper book at its own game. The Kindle has a few very significant new things going for it, mainly an Internet connection and integration with the world’s largest online bookseller, and Jeff Bezos is betting that it might finally strike the balance required to attract larger numbers of readers: doing a respectable job of recreating the print experience while opening up a wide range of digital affordances.

Steven Levy’s Newsweek cover story, “The Future of Reading,” is pegged to the much anticipated release of the Kindle, Amazon’s new e-book reader. While covering a lot of ground, from publishing industry anxieties, to mass digitization, Google, and speculations on longer-term changes to the nature of reading and writing (including a few remarks from us), the bulk of the article is spent pondering the implications of this latest entrant to the charred battlefield of ill-conceived gadgetry which has tried and failed for more than a decade to beat the paper book at its own game. The Kindle has a few very significant new things going for it, mainly an Internet connection and integration with the world’s largest online bookseller, and Jeff Bezos is betting that it might finally strike the balance required to attract larger numbers of readers: doing a respectable job of recreating the print experience while opening up a wide range of digital affordances.