Email killed the practice of letter-writing so suddenly that we haven’t a chance to think about the consequences. The Times Book Review ran an essay this weekend on the problem this poses for literary historians, biographers and archivists, who long have relied on collected letters and papers to fill in the gaps between a writer’s published work. In the same review, the Times covers a new biography of the legendary critic Edmund Wilson largely based on his correspondences, and last week covered a new collection of the letters of poet James Wright. Letters are often treated as literature in themselves.

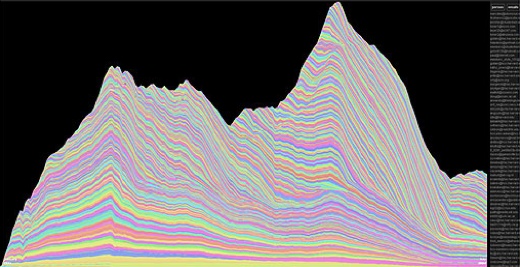

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

But a crop of writers is working now whose papers are not in order. The email is rotting away on the network, unorganized, not backed-up, and, to a great extent, simply being lost for good. I actually mused about this in a post last month about an email archive visualization tool by Fernanda Viégas at M.I.T.’s Sociable Media Group that shows years of electronic correspondence as sedimentary levels in a mountain-like mass. And a mountain it is. One novelist I know in Washington has her office stacked high with milk crates containing printouts of each and every email she sends and receives, no matter how trivial. There has to be a better way.

There isn’t necessarily anything less rich about email correspondence. It excels at capturing a vibrant volley of words with great immediacy, whereas paper letters permit deeper communiques, fewer and father between. But in some cases, these characterizations do not hold up. With reliable postal service, letters can fly back and forth quite rapidly. And just because an email suddenly appears in your box does not mean that it will be immediately read, let alone replied to. Sometimes we write long email letters, expecting that the receiver is busy and will take time to reply. These differences, true and false, are worth evaluating.

But if collected emails are to become a literary tool, there is no question that we will need more reliable ways of archiving and preserving digital correspondence. We will also need new editorial approaches for collecting and publishing them. A printed volume, or series of volumes, might be insufficient for presenting a massive 4 gigabyte email archive by Dave Eggers (No one wants to read the phone book from cover to cover). And according to the Times piece, Eggers’ agent Andrew Wylie is mulling over such a project. What would make more sense is an electronic edition that is essentially a selected or complete annotated Eggers Outbox, with folders and tags provided for categorization, a powerful search function, and the ability to organize according to your own interests. There would also be browsing and skimming tools that would allow a reader to move rapidly across vast tracts of correspondence and still find what they are looking for. And maybe, a way to email the author yourself and become a part of the living archive.

Category Archives: books

the blog as a record of reading

An excellent essay in last month’s Common-Place, “Blogging in the Early Republic” by W. Caleb McDaniel, examines the historical antecedents of the present blogging craze, looking not to the usual suspects – world shakers like Martin Luther and Thomas Paine – but to an obscure 19th century abolitionist named Henry Clarke Wright. Wright was a prolific writer and tireless lecturer on a variety of liberal causes. He was also “an inveterate journal keeper,” filling over a hundred diaries through the course of his life. And on top of that, he was an avid reader, the diaries serving as a record of his voluminous consumption. McDaniel writes:

While private, the journals were also public. Wright mailed pages and even whole volumes to his friends or read them excerpts from the diaries, and many pages were later published in his numerous books. Thus, as his biographer Lewis Perry notes, in the case of Wright, “distinctions between private and public, between diaries and published writings, meant little.”

Wright’s journaling habit is interesting not for any noticeable impact it had on the politics or public discourse of his day; nor (at least for our purposes) for anything particularly memorable he may have written. Nor is it interesting for the fact that he was an active journal-keeper, since the practice was widespread in his time. Wright’s case is worth revisiting because it is typical — typical not just of his time, but of ours. It tells a strikingly familiar story: the story of a reader awash in a flood of information.

Wright, in his lifetime, experienced an incredible proliferation of printed materials, especially newspapers. The print revolution begun in Germany 400 years before had suddenly gone into overdrive.

The growth of the empire of newspapers had two related effects on the practices of American readers. First, the new surplus of print meant that there was more to read. Whereas readers in the colonial period had been intensive readers of selected texts like the Bible and devotional literature, by 1850 they were extensive readers, who could browse and choose from a staggering array of reading choices. Second, the shift from deference to democratization encouraged individual readers to indulge their own preferences for particular kinds of reading, preferences that were exploited and targeted by antebellum publishers. In short, readers had more printed materials to choose from, more freedom to choose, and more printed materials that were tailored to their choices.

Wright’s journaling was his way of metabolizing this deluge of print, and his story draws attention to a key aspect of blogging that is often overshadowed by the more popular narrative – that of the latter-day pamphleteer, the lone political blogger chipping away at mainstream media hegemony. The fact is that most blogs are not political. The star pundits that have risen to prominence in recent years are by no means representative of the world’s roughly 15 million bloggers. Yet there is one crucial characteristic that is shared by all of them – by the knitting bloggers, the dog bloggers, the macrobiotic cooking bloggers, along with the Instapundits and Daily Koses: they are all records of reading.

The blog provides a means of processing and selecting from an overwhelming abundance of written matter, and of publishing that record, with commentary, for anyone who cares to read it. In some cases, these “readings” become influential in themselves, and multiple readers engage in conversations across blogs. But treating blogging first as a reading practice, and second as its own genre of writing, political or otherwise, is useful in forming a more complete picture of this new/old phenomenon. To be sure, today’s abundance makes the surge in 18th century printing look like a light sprinkle. But the fundamental problem for readers is no different. Fortunately, blogs provide us with that much more power to record and annotate our readings in a way that can be shared with others. We return to Bob’s observation that something profound is happening to our media consumption patterns.

As McDaniel puts it:

…readers, in a culture of abundant reading material, regularly seek out other readers, either by becoming writers themselves or by sharing their records of reading with others. That process, of course, requires cultural conditions that value democratic rather than deferential ideals of authority. But to explain how new habits of reading and writing develop, those cultural conditions matter as much–perhaps more–than economic or technological innovations. As Tocqueville knew, the explosion of newspapers in America was not just a result of their cheapness or their means of production, any more than the explosion of blogging is just a result of the fact that free and user-friendly software like Blogger is available. Perhaps, instead, blogging is the literate person’s new outlet for an old need. In Wright’s words, it is the need “to see more of what is going on around me.” And in print cultures where there is more to see, it takes reading, writing, and association in order to see more.

(image: “old men reading” by nobody, via Flickr)

the light of the disk is endless

“The cover of the book was rubbed with a patina made from lamp black, Yakskin glue, and brains. It was burnished to a gloss and inscribed with an ink made from crushed pearls and silver.” That is a description of the one of the Tibetan monastic manuscripts, or pothi, that Jim Canary discussed in his recent presentation, “The Tibetan Book: From Pothi to Pixels and Back Again,” at The Changing Book Conference (University of Iowa). Pothi were originally made of palm leaves. They are up to four feet in length and thin in shape; consisting of loose leaves in cloth covers pressed between wooden boards. They are sometimes housed in wooden boxes that resemble child-sized coffins. The Tibetan pothi are stored in long, narrow pigeon holes built into the walls surrounding the chanting area of the temple. Jim showed us a picture of these impressive libraries, with ceilings so high, the walls, and their overstuffed catacombs, disappear into darkness.

Jim Canary has over sixty of hours of video, taken during his trips to Tibet, documenting the monastic printing process. He plans to edit and publish the video as a CD Rom in tandem with a print book. He showed us some selections, which I do not have, so I will do my best to describe them. Video #1: a man sits on the stone steps outside the temple. There are two tall stacks of paper next to him and a bowl of water in front of him. He is preparing the paper for printing, taking one sheet from the top of the pile, passing it through a pan of water and placing it on top of the other pile. He has hundreds of sheets to dampen, so he is working in a brisk rhythmic manner. When he’s finished, the stack will be pressed between two wooden blocks. Video #2: printing takes place in a building across from the temple. The printing is done in teams of two. One man holds the hand-carved wooden block and prepares it with ink. His partner places each damp sheet on the wooden block for burnishing, then removes it and sets it aside to dry. The men work quickly in tandem, surrounded by the music of monks chanting in the temple next door. The tone and rhythm of the chant matches the rhythm of their work. It is designed to correspond with the heart beat, and it works to knit all participants together into a single, metaphorical “body” which is, in turn, joined to all humanity through the meditation. The result of all this unity is a book, shaped like a body, which will be housed, along with hundreds of others, in the temple walls.

Mr. Canary’s presentation was also about the future of these mystical books, which are being cataloged, preserved, reproduced and distributed using digital technology. Some monks are now working on laptops, transcribing text and burning DVDs. Here is an excerpt from a poem written by one of the monks in praise of digital materials, which, in his eyes, are as exquiste as a patina made from lamp black, Yakskin glue, and brains, burnished to a gloss and inscribed with an ink made from crushed pearls and silver are to me.

…The light of the disk is endless

like the light of the disks in the sky, sun and moon.

With a single push of our finger on a button

We pull up the shining gems of text…

-Gelek Rinpoche

light reading

“The Book as Object and Performance exhibition (through January 22 @ Gigantic Art Space in New York, curated by Sara Reisman) presents work by over 20 artists, each using the book as a point of departure to explore the physical, sensual or conceptual dimension of reading and the written word.

“The Book as Object and Performance exhibition (through January 22 @ Gigantic Art Space in New York, curated by Sara Reisman) presents work by over 20 artists, each using the book as a point of departure to explore the physical, sensual or conceptual dimension of reading and the written word.

But despite lofty ambitions, the exhibit provides little more than light reading. Though several works are visually arresting, few do more than glide over the potentially bottomless themes at hand. Most stick to playful reorganization of materials: a pile of wooden hoops culling newspaper headlines from around the globe; a precarious tower of books with a gaping acid-chewed hole at the top; a doorway filled with crumpled sheets of paper; a dictionary with words dislocated from their definitions. A collection of small, easily forgotten pleasures.

An exception to this is a mysterious piece titled “Perseverance” by Jenny Perlin consisting of a small, worn book in a glass case, above which plays a strange film of man battling anxiety, chewing his nails to the quick. Also memorable was a one-night-only “reading” of the ten commandments by Polish-born artist Maciej Toporowicz, a piece first performed in communist Poland in 1980, and part of small program of live explorations last night, filling out the “performance” part of the equation. The gallery lights are extinguished and Toporowicz takes his place in front of an illuminated glass bowl of water, perched atop an open Bible. He places his face in the water, as though reading through the aqueous medium, and remains there long enough for the audience to start imagining.. what? That he is drowning in this sacred, much-abused text? That he is drawing impossible sustenance from its power? He begins to twitch and tremble. Finally his head rips up out of the water, gasping.

The photo above shows bottles containing philosophical texts that have been literally chewed up and spit out. Click below to see more pictures from the exhibition…

Children and Books: Forming a World-View

When I think about the part books played (and still play) in forming my world-view, I have to think about them as tethered to a set of circumstances. It is impossible to say, for example, whether it was Gardner’s Art Through the Ages that awakened my passion for visual art, or my teacher Gretchen Whitman, who introduced the book to me and led me through it.

The book is part of a matrix that is difficult to parse. How is one’s world-view formed? Certainly books are a part of the process, but maybe they function more as “tools” then as “beings.” Insofar as they are extensions of the people or circumstances that drove us to them. With this in mind, it’s not surprising that very few of these lists are the same.

It’s interesting that nobody confesses that children’s books formed their world-view. I was profoundly influenced by the books I read when I was a child. The Little House on the Prairie series, and the Wizard of Oz still resonate with me. Dorothy and Laura Ingalls were pioneers–girl scouts, who were always prepared and never complained. They were independent, pragmatic survivors. I’m not saying this is the best collection of virtues one could strive for, but, nevertheless I recognize them in myself and think they were engendered, to some extent, by those books. Also, I must mention the fantastic strangeness of Dr. Seuss (who prepared me for surrealism), Maurice Sendack, Shel Silverstein, The Giving Tree, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Hans Christian Anderson.

Children’s books are there at the beginning, digging into our consciousness. The fact that children must, initially, be read to, illuminates something about how the book functions for humans. My son is 14 months old and he loves books. That is because his grandmother sat down with him when he was six months old and patiently read to him. She is a kindergarten teacher, so she is skilled at reading to children. She can do funny voices and such. My son doesn’t know how to read, he barely has a notion of what story is, but his grandmother taught him that when you open a book and turn its pages, something magical happens–characters, voices, colors–I think this has given him a vague sense of how meaning is constructed. My son understands books as objects printed with symbols that can be translated and brought to life by a skilled reader. He likes to sit and turn the pages of his books and study the images. He has a relationship with books, but he wouldn’t have that if someone hadn’t taught him. My point is, even after you learn to read, the book is still part of a complex system of relationships. It is almost a matter of chance, in some ways, which books are introduced to you and opened to you by someone.

I think people who are resistant to electronic books worry that this intimacy will be lost in a non-paper format. But clearly, it’s not the object itself, it’s the meaning brought to it by and through people. The medium won’t really change that.

books behind bars – the Google library project

How useful will this service be for in-depth research when copyrighted books (which will account for a huge percentage of searchable texts) cannot be fully accessed? In such cases, a person will be able to view only a selection of pages (depending on agreements with publishers), and will find themselves bombarded with a variety of retail options. On a positive note, the search will be able to refer the user to any local libraries where the desired book is available, but still, the focus here remains squarely on digital texts as simply a means of getting to print texts.

Absent a major paradigm shift with regard to the accessibility and inherent virtue of electronic texts, this ambitious project will never achieve its full potential. For someone searching outside the public domain, the Google library project may amount to nothing more than a guided tour through a prison of incarcerated texts. I’ve found this to be true so far with Google Scholar – it turned up a lot of interesting stuff, but much of it was password protected or required purchase.

article in Filter: Google — 21st Century Dewey Decimal System (washingtonpost.com)

Live from “Scholarship in the Digital Age” Conference at USC: The New Story

Scholarship in the Digital Age

This morning’s presentations got me thinking more about the narrative of the future–the multilayered, accreted story style that John Seely Brown referred to. How is that story going to be told and received? Will the novel become the dinosaur of alphabetic literacy?

Is the new book going to be a game, conversation, multi-layered, multi-authored, highly mutable and never-ending story? Assuming that the story is a conceptual device the culture uses to deconstruct reality, to make meaning, and to create, in some cases, a kind of anthem to rally around, what happens when our traditional narrative structures are replaced? If the single author, plot-driven novel is not the form of the future, then what do you get when you ask a million gamer/authors to shape an epic on the fly? What happens to our perception of reality if our stories are unstable, mutable, and open source?

NYPL ebook collection leaves much to be desired

I just checked out two titles from the New York Public Library’s ebook catalog, only to learn, to my great astonishment, that those books are now effectively “checked out,” and cannot be downloaded again by anyone else until my copies time out.

It boggles the mind that NYPL would go to the trouble of establishing a collection of electronic titles, only to wipe out every advantage offered by digital texts. In fact, they do more than simply keep the ebooks on the level of print, they limit them further than that, since there are generally multiple copies of most print titles in the NYPL system.

The people responsible for this catalog have either entirely failed to grasp the concept of infinitely accessible, screen-based books, or they grasp it all too well and are trying to stunt it at its inception, perhaps out of fear of extinction of the print librarian. More likely, they are under heavy pressure by a paranoid copyright regime. Whatever the reason, the new ebook catalog shows a total lack of imagination and offers nearly no tangible benefit for the reader.

Beyond that, the books themselves are poorly designed and unpleasant to read. My downloaded copy of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (which, by the way, I found in the “Romance” section) evidences no more than ten minutes worth of design work, and appears to be simply a cut-and-pasted ASCII file from Gutenberg with a garish graphic slapped on the cover. My copy of Chain of Command by Seymour Hersh was a bit more respectable – more or less a pdf facsimile of the print edition.

On an amusing note, the “literary criticism” section is populated almost entirely by Cliff’s Notes.

3,000 electronic titles at new york public library

This is the third Times article this week on e-books. What’s happening?

“Libraries Reach Out, Online”

No Need to Click Here – we’re just claiming our feed at Feedster

An Exchange With Alan Kay

Hi Bob –

I’ve been asked questions like this several times in the past, and have never been able to come up with a satisfactory answer. I estimate that I’ve read between 15,000 and 20,000 books, with about 1/10th of these being really worthwhile, and perhaps another 1/10th or more really useful as “how not to think about it” that serve as a large field of comparative and contrasting ideas. I think a central answer to your question from me is that I would simply not have my world view if it weren’t for books, and not just a few books but the wealth of multiple perspectives that the printing press made possible and encouraged.

The most important events in my life were learning how to read fluently before school age, and having read many books by the time I got to the constricting dogmas of school learning. This allowed me to resist and to gradually build my own mind, again largely through reading. I believe this is also an important answer to much of the good that has happened in the last 400 years. It’s hard to pick 3 books that changed the world, but there is no doubt in my mind that the combination of new kinds of argumentation and many more points of view from thousands of books broke apart a lot of the rigidity of thought that has characterized most of human existence. Sorry, best I can do …

P.S. If you had to pick one for the 17th century, it would be Newton’s Principia Mathematica. I came upon this in my late 20s or early 30s and it would be my pick for the number one “amazing book” ever written. However, my course and POV were already set by the time I actually got around to buying and reading it.

Cheers, Alan

to which Bob replied:

So . . . do you think books are playing the same role today as they did 40-50 years ago when we were growing up? My instinct is no . . . but even if i’m right, i’m not sure if it is because times are different or because the media landscape has changed so dramatically.

to which Alan replied:

No [in answer to “do you think books are playing the same role today … ] and I think that much of the new technology in the 20th and 21st centuries has been used to automate old oral forms (telephone, radio, movies, TV, voice mail, etc.) and this has taken quite a bit of day to day reading and writing out of most peoples’ lives. We are wired for oral discourse and most are happy to stay there. The larger scheme of things was greatly aided by having writing be the only long distance replicable technology around for a long time — and given that only 1% in Europe in 1400 could read, it really took the printing press to spread the hard to learn and literally mind-changing technology around sufficiently.

Also, McLuhan and Postman were pretty much right: that TV, especially, is a media form that delivers a 24 hour wall to wall environment that seems total, but lacks many important message carrying (and carrier) properties that the “written symbolic” media has. So, it’s not that TV actually tells people how to think, but, as an environment, it is what people try to learn to be fluent in and adapt to, and this makes it difficult for most people to formulate non-TV kinds of thoughts (many of which have been critical to the development of the last 400 years). And TV is much easier to “learn”. In simple: if you don’t read and think for fun, you won’t be fluent enough to read and think for purpose. This is why, when asked, I advise parents to treat TV and other similar media (including computer) like a cabinet of loaded guns or liquor. Locking it up is good, but not having in the house is probably better. But, since they are avid TV watchers and non-readers themselves, this advice has no effect. I think things are getting worse in part because TV is progressively making many more bad ideas seem normal.

Cheers, Alan

…and again, later on…

Hi Bob –Your questions got me thinking about certain books over the years. I stand by my earlier claim that it was the totality of many many books that did the job on me. But, still, there were a few, especially some very early ones that got me thinking one way and not another. For example, the first adult book I read all the way through — maybe at age 4 – was my father’s copy of Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. I originally read it because I had gotten interested in the ancient Greeks (he was quite interested). But the last part of the book contained Norse myths and these were in some cases similar to the Greek ones. This got me to realize that these were just stories and needed more than claims to back them up. This helped tremendously in resisting the Bible during later attempts to force this on me. Another early book was a long one, also my Dad’s, Breasted’s Ancient Times, maybe read at age 6 or 7. Again, I originally started reading it because I though ancient (and “lost”) civilizations were cool (and loved the different architectures, etc.). But, I started to realize that human beings are driven to similar forms under similar conditions, etc. This led me to Anthropology later on.

A Life Magazine on the Holocaust (published in 1945, but I saw in 1947 at age 7)completely horrified me, and made me afraid of adults to this day (and rightly so).This was likely one of the earliest insights and shocks that motivated my later long standing interests in helping children to think better than most adults do today. Willi Ley’s Rockets, Missiles and Space Travel around age 8 had a big effect. One memory from this book was the strange idea that you couldn’t just aim a rocket at the planet you wanted to go to, but had to create an orbit for the rocket that would cause it and the planet to meet many months in the future. I can’t quite explain why this had such a big effect on me. Science fiction, especially of Robert Heinlein, A. E. van Vogt, etc., had a huge effect, and got me to read many deeper books, like Korzybski’s Science and Sanity. To have a conversation with a professor who didn’t like grad students but did like McLuhan, I spent the better part of the summer of 67 really understanding Gutenberg Galaxy and Understanding Media. This was one of the biggest most useful shocks I got from a book. Marvin Minsky’s Computation: Finite and Infinite Machines had a great effect on getting me to think more mathematically about computing (maybe 1968), and this led to McCarthy’s meta definition of LISP in the LISP 1.5 Manual (a book of sorts), which was the key to really inventing objects “right”. And so forth …

Cheers, Alan