Near future science fiction is a reflexive art: the present embellished to the point of transformation that, in turn, influences how we envision, and eventually create our future. It is not accurate—far from it—but there is power in determining the vocabulary we use to discuss a future that seems possible, or even probable. I read Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash in 2000 and thought it was a great read back then. I was twenty-five, the internet was tanking, but the online games were going strong and the Metaverse seemed so close. The Metaverse is an avatar inhabited digital world—the Internet on ‘roids—with extremely high levels of interactivity enabled by the combination of vast computing power, 3-D tracking gloves (think Minority Report), directional headphones, and wraparound goggles that project a fully immersive experience in front of your eyes. This is the technophilic dream: a place where physicality matters less than the ability to manipulate the code. If you control the code, you can make your avatar do just about anything.

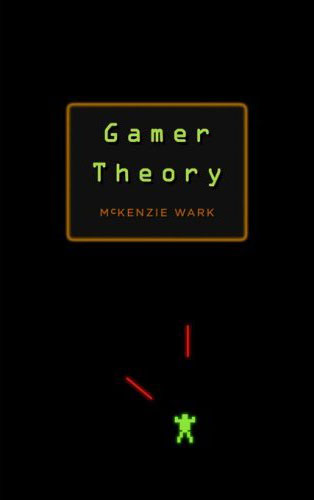

Now, five years later, I’ve reread Snow Crash. It continues to be relevant. The depiction of a fractured, corporatized society and of the gulf between rich and poor are more true now than they were five years ago. But there is a special resonance with one idea in particular: the Metaverse. The Metaverse is what many people dream the Internet will eventually become. The Metaverse is, as much as anything, a place to hang out. It’s also a place to buy ‘space’ to build a house, a place for ads to be thrown at you while you are ‘goggled in,’ a place for people to trade information. In 2000, in reality, you would have a blog and chat with your friends on AIM. It didn’t have the same presence as an avatar in the Metaverse, where facial features can communicate as much information as the voice transmission. Even games, like Everquest, didn’t have the same culture as the Metaverse, because they were games, with goals and advancement based on game rules. But now we have Second Life. Second Life isn’t about that—it is a social place. No goals. See and be seen. Make your avatar look the way you want. Buy and build. Sell and produce your own digital culture. Share pictures. Share your life. This is closer to the Metaverse than ever, but I hope that doesn’t mean we’ll get corporate franchise burbclaves as well. Well, at least any more than there already are.

I also reread The Diamond Age. This is a story about society in the age of nanotech and the power of traditional values in an environment of post-materialism. When everything is possible through nanotech, humanity retreats to fortresses of bygone tradition to give life structure and meaning. In the post-nation-state society described in the book, humans live in “phyles,” groups of people with like thoughts and values bound together by will and rules of society. Phyles are separated from each other by geography, wealth, and status; phyle borders are vigorously protected by visible and invisible defenders. This separation of groups by ideology seems especially pertinent in light of the continuing divergence of political affiliation in the US. We live in a politically bifurcated society; it is not difficult to draw parallels between the Red state/Blue state distinction, and the phyles of New Atlantis, Hindustani, and the Celestial Kingdom.

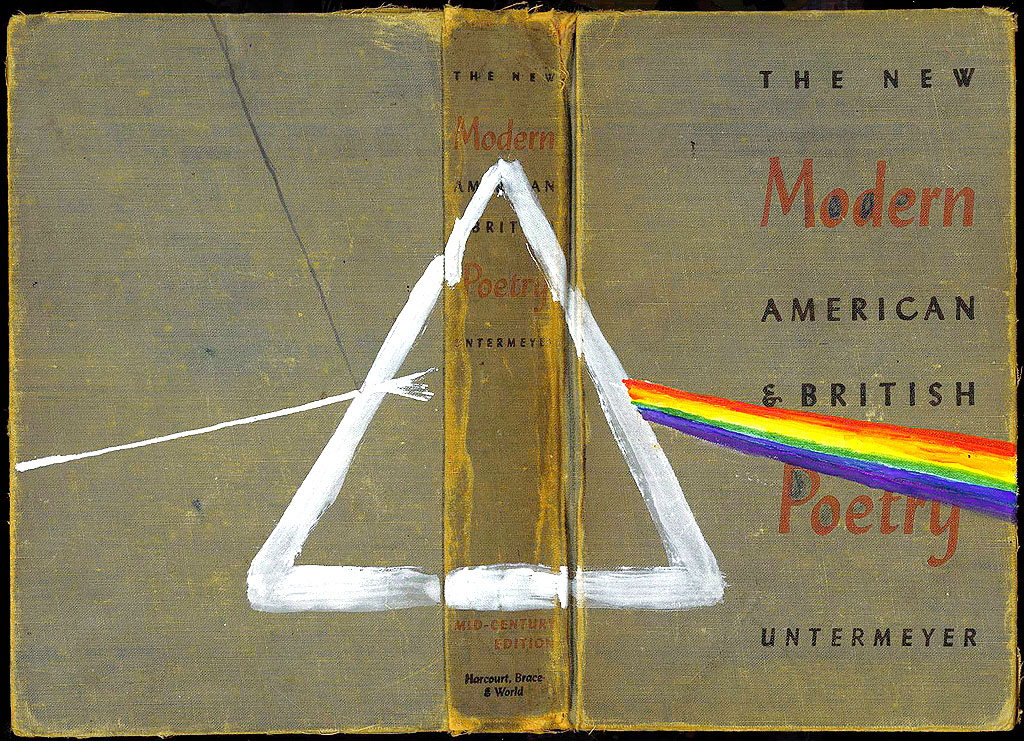

The story focuses on a girl, Nell, and her book, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. The Primer is her guide through a difficult and dangerous life. Her Primer is scientifically advanced enough that it would, if we had it today, appear to be magic. The Primer is aware of its surroundings, and aware of the girl’s position in the surroundings. It is capable of determining relationships and decorating them with the trappings of ‘story’. The Primer narrates the story using the voice of a distant actor, who is on call, connected through the media system (again, the Internet but so much more). The Primer answers any questions Nell asks, expounds and expands on any part of the story she is curious about until she fully satisfies her curiosity. It is a perpetually self-improving, self-generating networked storybook, with one important key: it requires a real human’s input to narrate the words that appear on the page. Without a human voice behind it, it doesn’t have enough emotion to hold a person’s interest. Even in a world of lighter than air buildings and nanosite generated islands, tech can’t figure out how to make a non-human voice convey delicate emotion.

There are common threads in the two novels that are crystal clear. Stephenson illluminates the near future with an ambivalent light. Society is fragile and prone to collapse. The network is likely to be monopolized and overrun with advertising. The social fabric, instead of being interwoven with multiethnic thread, will simply be a geographic patchwork of walled enclaves competing with each other. Corporations (minus governments) will be the ultimate rulers of the world—not just the economic part of it, but the cultural part as well. This is a future I don’t want to live in. And here is where Stephenson is doing us a service: by writing the narrative that leads to this future, he is giving us signs so that we can work against its development. Ultimately, his novels are about the power of human will to work through and above technology to forge meaning and relationships. And that’s a lesson that will always be relevant.

The iPod is, as skeptics initially complained, little more than a hard drive with earphones. But this is precisely its genius: the simplicity of its interface, the sleekness of its form, the radical smallness of its immense storage capacity. All these allow us to spend less time sorting through our music — lugging around stacks of albums, ejecting and inserting tapes or discs — and more time listening to it.

The iPod is, as skeptics initially complained, little more than a hard drive with earphones. But this is precisely its genius: the simplicity of its interface, the sleekness of its form, the radical smallness of its immense storage capacity. All these allow us to spend less time sorting through our music — lugging around stacks of albums, ejecting and inserting tapes or discs — and more time listening to it.