If you’re in the New York area, don’t miss this. Friday, March 21, 2008, 7-9pm – ?New York, NY – ?125 Maiden Lane, 2nd Floor.

FOR ONE NIGHT ONLY: Step inside three books, drink free beer and wine, and experience the future of the book:

Mark Batty Publisher, Hotel St. George Press, the Institute for the Future of the Book, and the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council‘s Workspace Writers Residency program offer a night of multi-media readings that invite attendees to step inside books, celebrating how new media and traditional publishing fuse to create innovative projects that are more than “just books.” On this night, authors Garth Risk Hallberg, Alex Rose, and Alex Itin demonstrate how their stories rely on more than just words.

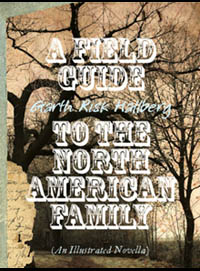

Hallberg’s illustrated novella, A Field Guide to the North American Family, documents two fictional families through 63 entries accompanied by evocative photographs contributed by some of today’s freshest photographic talents, as culled from the book’s ongoing companion website, afieldguide.com. Read from start to finish or in a “choose your own adventure” style, Hallberg’s attention to narrative detail makes clear why he was included in the 2008 Harcourt Best New American Voices anthology, and why Print called A Field Guide to the North American Family “a modern illuminated manuscript.” Hallberg will project photographs from the book.

The interwoven, post-modern folktales that comprise The Musical Illusionist by Alex Rose muse upon historical arcana, tethered together by music and topography. Drawing on his experience as a director whose films, videos, and animations have appeared on HBO, MTV, Comedy Central, Showtime, and the BBC, Rose conjures, in the words of the Village Voice, “the playful parables of Jorge Luis Borges . . . exotic maps and exquisite prints further suggest a volume passed down from an epoch much more enthralled with mystery than our own.” Rose will read from the title story of his collection, accompanied by a surround-sound score composed by David Little and recorded by the Formalist Quartet.

As an artist-in-residence at Brooklyn’s Institute for the Future of the Book, Alex Itin uses text, original illustrations and animations, and music to encourage readers to reconsider the definition of a book. Take for example Itin’s Orson Whales: Melville’s Moby Dick meets Orson Welles, and Led Zeppelin. Itin’s multi-media books will be screened.

The LMCC is the leading voice for arts and culture in downtown New York City, producing cultural events and promoting the arts through grants, services, advocacy, and cultural development programs.