On Thursday October 9th, National Poetry Day in the UK, 2008 if:book london is launching an exciting experiment in reading and writing, supported by Arts Council England. Over the next six months I will be working with artist and web designer Toni Lebusque, project manager and film maker Sasha Hoare and a team of inspired people to create an illuminated book online, containing the poetry of William Blake, new writing, art and song inspired by Blake’s work, and the voices of many readers as they debate some of Blake’s key concerns and their relevance in the digital age.

Why Blake? Well, just imagine what William Blake’s blog would look like. Think what this radical, visionary maker and publisher of multimedia books would have made of the web.

I came across Songs of Innocence & Experience as a teenager, before teachers could convince me he was difficult. My great grandfather was a Blake scholar, and I found reproductions of the illuminated books on my grandmother’s shelves; they soon inspired me to churn out epic poems of mythical worlds, to write them out neat in an exercise book and embellish them with crayons and felt tip pens. ‘This is a world of Imagination & Vision’ he wrote, which I took to mean, ‘Go for it!’

Blake has been an inspiration to generations of real artists too, from Allen Ginsberg to Jah Wobble, a source of Imagination and Vision to all kinds of readers, yet he’s also been colonized by the academics, judged obscure on one hand, nuts on the other.

Blake railed against the treatment of Chimney Sweepers and working Londoners locked in the mind forg’d manacles of man; he conjured up vivid images of nature enhanced by symbolism and transformed by imagination; he celebrated the importance of freedom in play for children. How would he react to London now, to the digital printshop, the sweatshop and call centre, the lack of spaces for kids to roam except online? What would Blake build in Second Life’s green and pleasant land? And what digital tools might he use to make what kind of books?

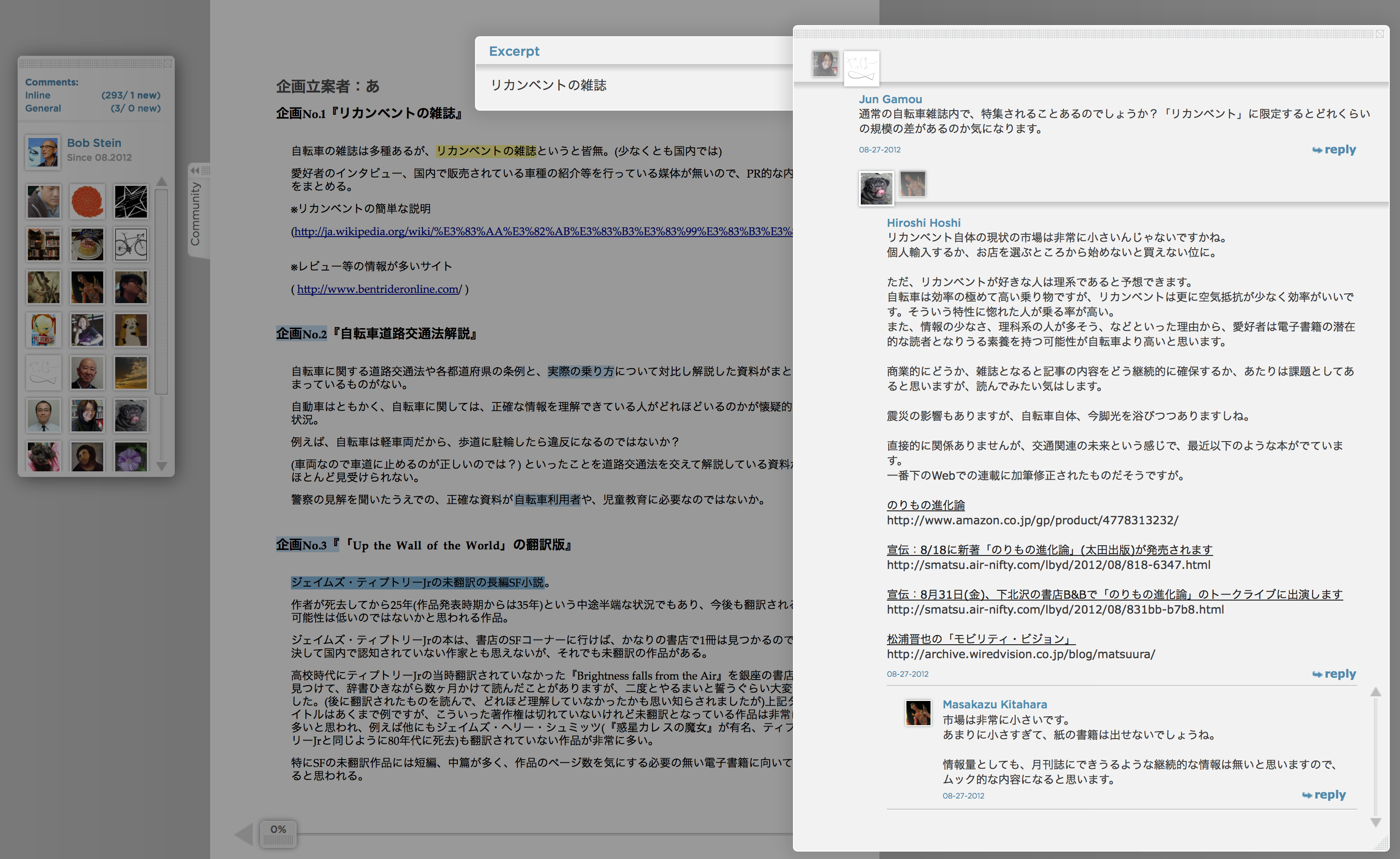

Bob Stein has talked of a new kind of curatorial role involved in the publishing of tomorrow; in his Unified Theory of Publishing he writes:

“far from becoming obsolete, publishers and editors in the networked era have a crucial role to play. The editor of the future is increasingly a producer, a role that includes signing up projects and overseeing all elements of production and distribution, and that of course includes building and nurturing communities of various demographics, size, and shape. Successful publishers will build brands around curatorial and community building know-how AND be really good at designing and developing the robust technical infrastructures that underlie a complex range of user experiences.”

I agree completely, but I’m not convinced that traditional publishing companies are best placed to take on this role. I’ve spent many years working with literature organisations like the Poetry Society and Booktrust, alongside professional workers with reader development projects in libraries and the community; our trade is the creation and execution of projects which bring writers and readers together, commissioning new work for specific settings. A good arts festival sparks conversations around the themes it explores and the events it makes happen.

The Poetry Places scheme we ran at the Poetry Society in the 1990s involved residencies, workshops, performances in all kinds of venues, and the creation of poems to be engraved into a public space, proclaimed at an event, used as signage in parks, zoos and estates…

People usually classified as ‘arts administrators’ are orchestrating interactions that are much more akin to Bob’s concept of the curator of the networked book than publishers who seem to find it hard to see much beyond a downloadable replica of their traditional product.

Songs of Imagination & Digitisation will involve working with a range of those people, commissioning new writing and art, providing incentives for new voices to submit work and for readers to give us their ideas. We will mingle film, text and image, reader response and author interviews – and once we’ve gathered enough ingredients on our blog we hope to transmute them into something that feels like a proper, substantial, networked book.

So many web projects go encyclopaedic and neverending. The book of the future will be linked to a community, open to revision and extension, but also bounded in a meaningful way, a satisfying artistic entity, porous but not pointless.

if:book kicks off this project on National Poetry Day. In the morning some of us will wander round Covent Garden and Soho, where Blake was born, and talk to people about their working lives. We’ll film them reading lines from Blake, then go and drink tea while actor Toby Jones reads us Blake poems and we respond to them in doodles, written words and conversation.

And that day the inspirational Bill Thompson will release into the wild a laptop loaded up with Blake’s work. For the next five months it will be passed from person to person, each one recording their responses, and emailing them to the Songsofimaginationanddigitisation.net blog

Over the next six month’s we’ll take a psychogeographical walk to Blake’s house in South Molton Street to discuss the city, gather at the Museum of Gardening near Hercules Buildings in Lambeth where Mr & Mrs Blake naked played Adam and Eve – allegedly. We’ll go to the Sassoon Gallery near Peckham Rye where young William saw angels in the branches of trees, and discuss the innocence and experiences of childhood then and now. We will be commissioning some writers, artists and musicians, offering eReaders and iTouches to others who contribute. We hope to build an international community of readers around our blog of the project’s progress, www.songsofimaginationanddigitisation.net, including students at all levels who have Blake as a set text. We want the Songs to be a springboard into all kinds of reading.

So – Tell us what you think of this Idea; Bookmark, RSS and Del.icio.us us; Send us your Blake related Poems, Stories, Photographs and Drawings; Together Let Us Sing Songs of Imagination & Digitisation!

The novelist Jonathan Lethem has been on a most unusual book tour, promoting and selling his latest novel and at the same time publicly questioning the copyright system that guarantees his livelihood. Intellectual property is a central theme in his new book,

The novelist Jonathan Lethem has been on a most unusual book tour, promoting and selling his latest novel and at the same time publicly questioning the copyright system that guarantees his livelihood. Intellectual property is a central theme in his new book,

Most of the prints exhibited at the UBS belong to Evans’ body of work documenting the effect of the Great Depression on rural families for the

Most of the prints exhibited at the UBS belong to Evans’ body of work documenting the effect of the Great Depression on rural families for the