I spent a day last week at MASS MoCA, touring Sol LeWitt: A Wall Drawing Retrospective. (It was finally profiled in the New York Times this morning, and NPR reported it yesterday.) The exhibit takes up an entire building, wall after wall installed for the (re)creation of LeWitt’s work. LeWitt did not want his work to be limited to a single canvas; he created careful records of each of his drawings so they could be produced on any wall by himself or other artists. He compared this to architecture and music; it can be reproduced and will vary depending upon the people and spaces involved in each production. He planned this exhibit well before his death last year.

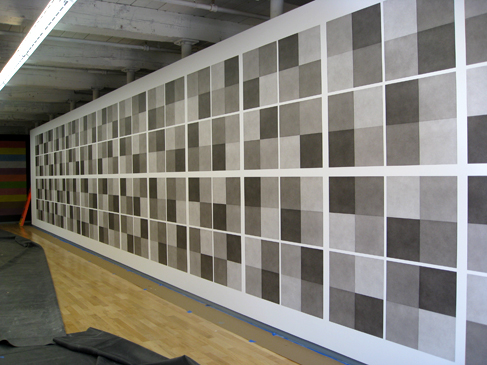

For the retrospective, MASS MoCA commissioned sixty-odd students and artists, among them Adrian Piper and Jerry Orter, to produce the wall drawings. Thousands of crayons, graphite pencils, colored pencils, and gallons of acrylic paint later, Building 7 was transformed into a celebration of LeWitt’s career.

Walking through the building is like walking through LeWitt’s brain: you can see his earliest experiments and echoes of these in his later work. These pieces are presented in a way that is varied and spectacular in the exhibit; I am going to present them below in a much more linear format, but you have to go visit to get the full effect. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos in this entry belong to MASS MoCA.)

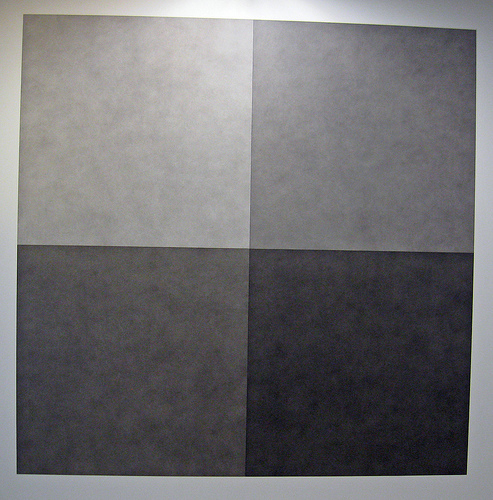

He begins with simple lines, and advances to levels of shading.

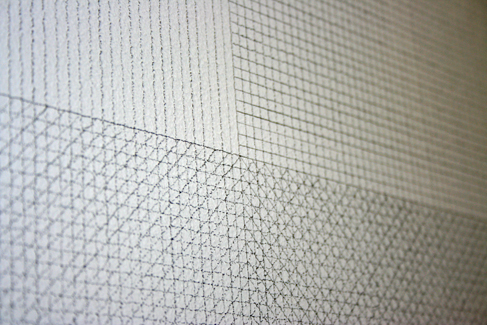

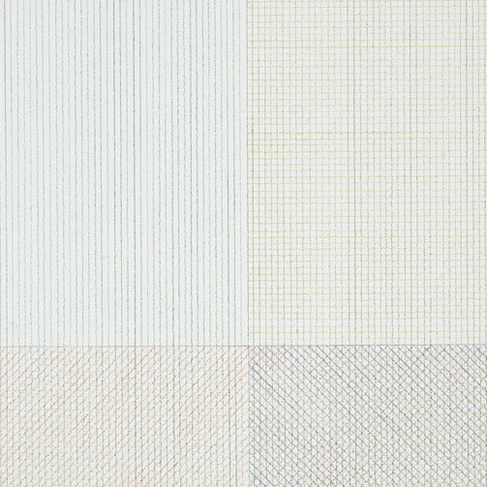

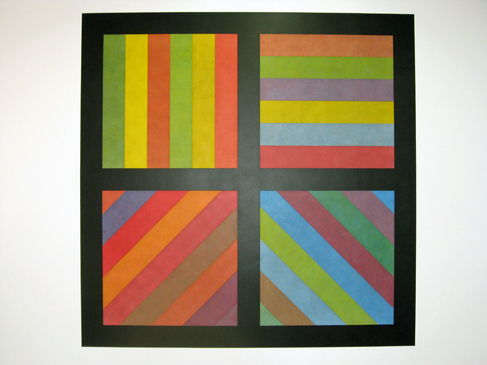

You can see his first foray into the world of color, then what seems to be his signature (four blocks) emerge from these. LeWitt doesn’t blend colors, he layers one color on top of another. He often uses diagonal lines coming from several directions in primary colors, in the following pattern: vertical, horizontal, diagonal left, and diagonal right. He superimposes these lines to create gradations in colors (or greys).

He places the blocks together like a quilt pattern that can span an enormous amount of space.

He (or rather, his talented production team) then blends color by carefully layering primary colors directly on the wall. The result is something like this:

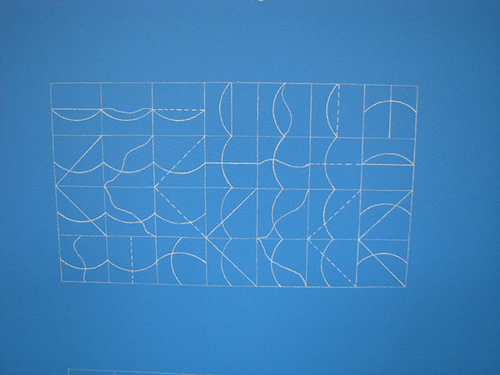

If you look carefully, you see the grids beneath his work. One piece, produced originally on white walls with blue lines, and produced in this retrospective on blue walls with white lines, is a clear demonstration of his lexicon. LeWitt uses music terms to explain how his work is produced. I must resort to linguistic terms to describe it – even the brochure slips into a description of his shapes as though they are language. This blue piece is the largest in the exhibit, showing each of the forms LeWitt used at the time, and presenting them all together on a grid. The grid is still visible in the finished product, and piece feels like a blueprint as well as a finished product. LeWitt worked with an architect for a time, and it’s hard not to compare his work to architecture, geometry, or even early computer programming (which was going on as some of his work was being created).

I’m including the second photo with people in it so you can imagine how your relationship with this piece will change when you see in on four walls that tower above you. A piece like this completely immerses the museum-goer the language of his compositions. As you explore, you can learn the syntax of each color, each painting technique, and each pattern. Once you understand the rules, the artist can break them. On the third floor, LeWitt throws walls at you like this:

That’s Wall Drawing 958, with the description “Splat.” LeWitt subverts his own vocabulary. He leaves behind the “Splat” plan on a sheet for an overhead projector – perhaps he grew less interested in the variation borne of multiple production teams and many different spaces. (If he had been a composer, this would be the point in his life where he records himself playing all the parts of a piece instead of leaving it up to interpretation.)

One of his later pieces that I especially like is below. Everyone who walked by seemed to comment upon its resemblance to a board game. The instructions LeWitt wrote say specifically that none of the same colors can touch, and no matter how carefully the draftsmen planned, they inevitably had to touch it up to make sure this order was preserved.

Sol Lewitt Wall Drawing #1112 & #1152 from jackadam on Vimeo.

His final pieces seem to wait quietly to the side while his brightest walls parade around the third floor. These quiet, distant pieces are scribble drawings made with graphite that bring a new level of depth to his work. Color bars have nothing on a spiral piece that appears to spin as it catches the light. NPR used the word “trippy” to describe the work on the third floor – it’s in motion, and it’s coming toward you.

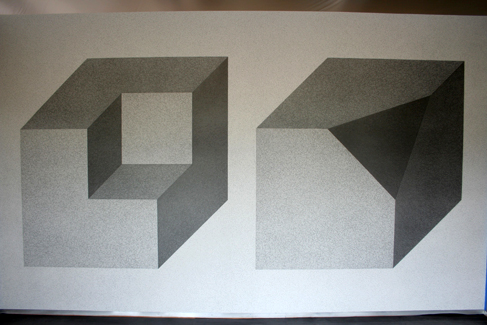

But a piece that stands out in the corner is Wall Drawing 1171. These is beside a few other graphite works that have no color, but add much dimension (this one can flip as you watch it).

The “cube without a cube” is a three-dimensional cousin of the earliest grey blocks, and in fact the earliest grey lines. It’s as though LeWitt found a favorite verb and conjugated it: grey line blocks, colored pencils block, dark acrylic wall blocks, bright acrylic wall blocks, graphite shapes block. I block, you block, we block.

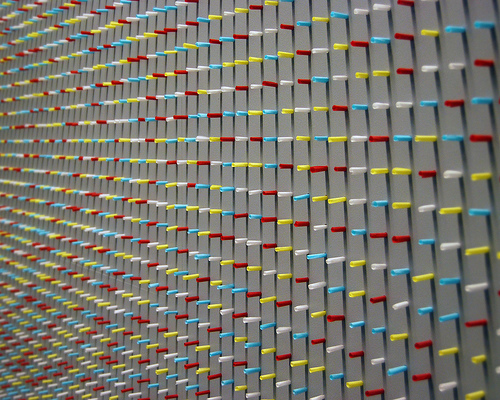

I hadn’t realized I had soaked in LeWitt’s language until I browsed the website and stumbled upon the caption below Wall Drawing 38. This is an unusual piece, employing a pegboard wall to hold thousands of tiny rolls of colored tissue paper. These pieces were supposed to be put in at random, but anyone can imagine how difficult it is to generate a random pattern that appears random – surely the draftsmen had to touch it up, the way they touched up Wall Drawing 1121 (in the video above).

Additionally, this piece is set on three walls: the first wall has yellow and white paper, the second has white, yellow and red, and the third has white, yellow, red, and blue.

The website reveals that this piece was designed for four walls. The first wall had only white tissue. This is a piece that conjugates the block formation with a fresh medium, and a three-dimensional one at that.

In this case, LeWitt wants you to be inside the blocks (on the second floor) before he removes a cube from a cube (on the third floor, at the end of his life). He makes use of the wall space to trap you, to make you more directly involved with his experiments in color and space. I like this play upon the theme.

LeWitt wrote, “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” This exhibit was created by anything but machine. It takes real chopsticks to get those pieces of tissue paper in the peg holes. You the viewer are invited to simultaneously study the artist’s plan, and also the interpretation of each plan within the architectural space, the interpretation and choices of the artists LeWitt knew, and finally the labor of the people who put these pieces together. It’s a very active form of taking in art. You often hear people dismiss modern art because they feel they could have done a piece themselves. In this exhibit, it’s true, and LeWitt wants you to. Let me know if you have the time and energy to create a wall like this in your house. Really, I’d love to see it.

There is a nice piece in The Believer about following LeWitt’s instructions, and a photo essay of the pieces going up.

We were discussing in the Who Built America meeting the way that academics, historians, and writers – many people in the humanities – prefer to keep their work isolated prior to publication. It is supposed to have had some sort of immaculate conception; one cannot reveal the mistakes or the rough edges prior to the moment other scholars see it.

MASS MoCA does an extraordinarily good job of revealing the process behind the exhibit. You can see LeWitt’s transparencies as you enter the exhibit, you can watch videos of some of the pieces going up. You can view the whole exhibit online, by grid or by floorplan, or listen to the audio tour. You can begin to synthesize the work for yourself.

A quite note to point out that LACMA has

A quite note to point out that LACMA has