A few weeks back though the auspices of TED, I paid a visit to a private library. The owner doesn’t want publicity, and I won’t reveal details, but it was a staggeringly beautiful (if idiosyncratic) collection, and I can’t imagine that there are many collections in private hands that rival it in value in the United States. Just about every lavish book imaginable was present: an elephant folio of Audobon along with a full set of John Gould‘s more sumptuous prints of birds; a Kelmscott Chaucer; a page from a Gutenberg Bible; a first edition of Johnson’s Dictionary; countless antique atlases of anatomy and cosmography; the Arion Press edition of Ulysses illustrated by Robert Motherwell; hand-illuminated Books of Hours. There were exquisite jeweled bindings, books woven entirely from silk, and doubtless many more things that couldn’t be seen in a three-hour tour. The collector mentioned in passing that he was thinking of buying a Wyclif Bible for around $600,000 because he didn’t have one yet.

Being no stranger to libraries, I’d seen many of these books before. Generally they’re the sort of books you see in the context of a museum or library, occasionally for sale in a gallery. They’re the sort of books that are generally found safely behind glass, books that one wears white gloves to touch. This was not such a collection: it’s not open to the public at all, only to the collector’s friends. A librarian would also be astonished that this collection of 30,000 books has no catalogue – the owner shelves all the books himself (by height, for which there’s historical precedent) and claims that he remembers where he put things. But what was most striking to me about my visit was how freely the books were handled by the owner, and how freely he allowed his guests to handle his books – not in a cavalier way, but in the way one touches a book one owns. The librarian in me suppressed a gasp when the owner explained how in the summer he opens the bay windows of the library and lets the breeze in. I’m sure that’s not how the Morgan Library works.

The collector can afford to let his visitors touch his books. In a way, the books in his collection are functioning as they are intended to function: as objects to be read and appreciated. They’re also functioning as signifiers of luxury. His collection is a repository of wealth in a way less metaphorical than we usually talk about library as repositories. No library, private or public, exists entirely outside of this economic system; it’s an integral part of the way we consider books.

Walking north on Laguardia Place last week, I was struck by how monolithic NYU’s Bobst Library appears from the south: it’s a hulking red-brick edifice that admits no entrance:

From inside it’s all windows and light, open stacks to be browsed. But: there’s the matter of getting inside, as admission is reserved to those with an NYU ID card. Those without cards are excluded. This is a necessary condition for the library to function: long ago on this blog I bemoaned the condition of the Brooklyn Library, where it’s almost impossible to find any book you’re looking for, though there’s still the pleasure of browsing. The quality of a collection seems to be inversely related to the number of people kept out. Keeping the books in and the world out is demonstrated elegantly by the thin marble windows of Yale’s Beinecke library which admit a small amount of light but not the viewer’s gaze:

What’s inside and outside – who’s inside and outside – are completely separated. The poet Susan Howe inspects this separation in her book The Midnight, a volume which takes as one of its primary subjects interleaves, the sheets of tissue paper that publishers once put next to plates in books “in order to prevent illustration and text from rubbing together.” Howe’s work tends to be archivally based: she looks at how manuscripts are read or misread, and consequently has spent a lot of time in libraries. In this prose passage from the book, part of a section entitled “Scare Quotes II”, she looks at the way one enters Houghton, Harvard’s analogue to the Beinecke:

1991. Entering Houghton Library: Harvard Yard, 9:00 a.m., a fine June summer morning. At the entrance to the red-brick building designed by Robert C. Dean of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn in 1940, two single wooden doors with hinges, concealing two modernist plate glass doors without frames, have been swung into recesses to the left and right so as to be barely visible during open hours. The only metal fitting in each glass consists of a polished horizontal bar at waist height a visitor must pull to open. I enter an oval vestibule, about 10 feet wide and 5–6 feet deep, before me double doors again; again plate glass.

Passing through this first vestibule I find myself in an oval reception antechamber about 35 feet wide and 20 feet deep under what appears to be a ceiling with a dome at its apex. I think I see sunlight but closer inspection reveals electric light concealed under a slightly dropped form, also oval, illuminating the ceiling above. This first false skylight resembles a human eye and the central oval disc its ‘pupil.’ Maybe ghosts exist as spatiotemporal coordinates, even if they themselves do not occupy space, even if you’ve never seen one, so what? If the design of the antechamber can be read in terms of power and regimes of library control, and if ghosts ‘presently’ ‘occupy’ papers, you need to understand the present tense of ‘occupy.’

To enter this neo-Georgian building (a few Modernist touches added) with its state of the art technology for air filtration, security and controlled temperature and humidity for the preservation of materials, is to turn away from contemporary city life with all its follies and parasites in search of a second coming for dry bones. When the soul of a scholar has an inward bent and bias for an author in the Kingdom of Houghton, it is never at rest, until here. Perversely, nothing in Houghton awakens security sooner than curiosity.

Here – every researcher can be a perpetrator.

( pp. 120–121) While Houghton isn’t as architecturally ostentatious as the Beinecke, Howe’s scrutiny of the architecture of its entrance reveals it to be just as concerned with control. There’s a pessimistic view of human behavior embedded in library construction and the watchfulness of the sentries who guard them: if we, the public, could get at the books, we would most certainly destroy them.

There was the expectation that the barriers would be torn down with the coming of electronic libraries, that once the book’s spirit left its object, it would likewise escape its economic shackles. Certainly it makes sense: an electronic text isn’t degraded by copying in the same way that every reading is an infinitesimal destruction of a physical book. It’s unclear, however, that the media universe that’s unfolding is following this pattern: while sites like archive.org present a new model, projects like Google Books simply reconfigure the gates.

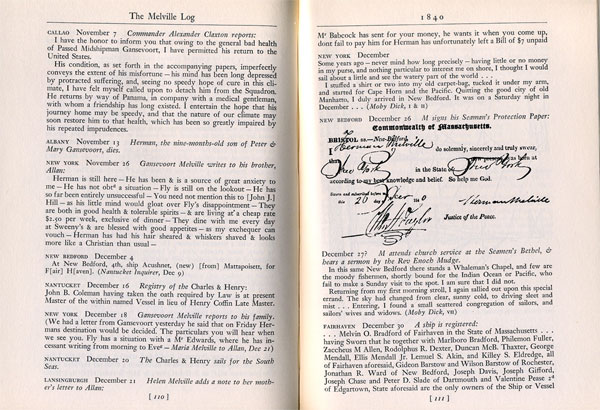

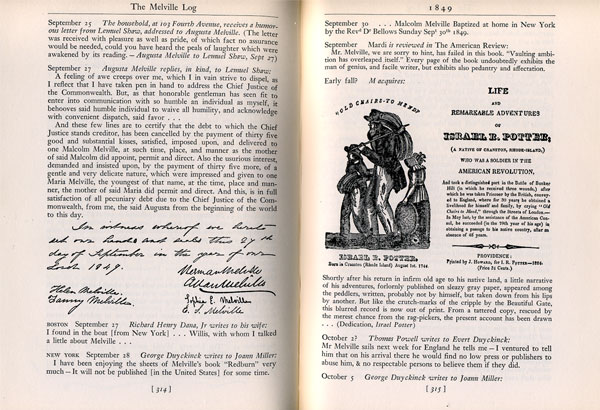

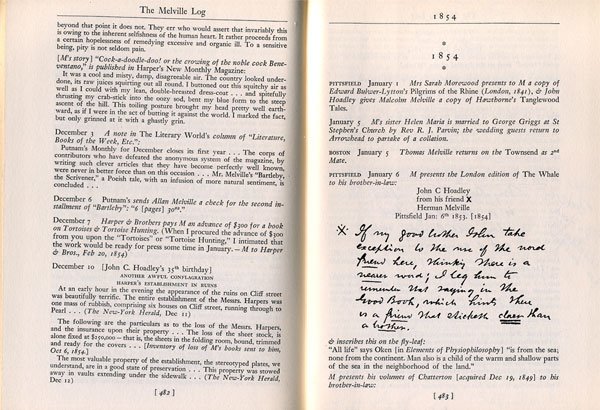

Jay Leyda, it turns out, wasn’t just a literary historian; in fact, he’s best known as a film historian, a field in which he played a foundational role. He had, it seems clear, an interesting life. Considering an career as a filmmaker, Leyda went to Moscow in the 1930s to study film with Eisenstein, the only American to do so; he seems to have worked on Bezhin Meadow as a stills photographer. Returning to the U.S., he served as an advisor to

Jay Leyda, it turns out, wasn’t just a literary historian; in fact, he’s best known as a film historian, a field in which he played a foundational role. He had, it seems clear, an interesting life. Considering an career as a filmmaker, Leyda went to Moscow in the 1930s to study film with Eisenstein, the only American to do so; he seems to have worked on Bezhin Meadow as a stills photographer. Returning to the U.S., he served as an advisor to

(

(

Then I started to think about loading in individual blog entries from the XML. I talked to my friend Mike about this for a while and in exchange for some brownies (although really only out of his extreme kindness and generosity) he constructed an XML format, sample.xml, and guided me on a way to load in the HTML of each individual entry into a small clip.

Then I started to think about loading in individual blog entries from the XML. I talked to my friend Mike about this for a while and in exchange for some brownies (although really only out of his extreme kindness and generosity) he constructed an XML format, sample.xml, and guided me on a way to load in the HTML of each individual entry into a small clip. The year-long Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit started last night at

The year-long Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit started last night at