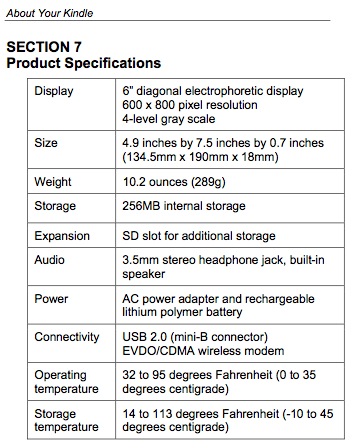

The NY Times reported yesterday that the Kindle, Amazon’s much speculated-about e-book reading device, is due out next month. No one’s seen it yet and Amazon has been tight-lipped about specs, but it presumably has an e-ink screen, a small keyboard and scroll wheel, and most significantly, wireless connectivity. This of course means that Amazon will have a direct pipeline between its store and its device, giving readers access an electronic library (and the Web) while on the go. If they’d just come down a bit on the price (the Times says it’ll run between four and five hundred bucks), I can actually see this gaining more traction than past e-book devices, though I’m still not convinced by the idea of a dedicated book reader, especially when smart phones are edging ever closer toward being a credible reading environment. A big part of the problem with e-readers to date has been the missing internet connection and the lack of a good store. The wireless capability of the Kindle, coupled with a greater range of digital titles (not to mention news and blog feeds and other Web content) and the sophisticated browsing mechanisms of the Amazon library could add up to the first more-than-abortive entry into the e-book business. But it still strikes me as transitional – ?a red herring in the larger plot.

A big minus is that the Kindle uses a proprietary file format (based on Mobipocket), meaning that readers get locked into the Amazon system, much as iPod users got shackled to iTunes (before they started moving away from DRM). Of course this means that folks who bought the cheaper (and from what I can tell, inferior) Sony Reader won’t be able to read Amazon e-books.

But blech… enough about ebook readers. The Times also reports (though does little to differentiate between the two rather dissimilar bits of news) on Google’s plans to begin selling full online access to certain titles in Book Search. Works scanned from library collections, still the bone of contention in two major lawsuits, won’t be included here. Only titles formally sanctioned through publisher deals. The implications here are rather different from the Amazon news since Google has no disclosed plans for developing its own reading hardware. The online access model seems to be geared more as a reference and research tool -? a powerful supplement to print reading.

But project forward a few years… this could develop into a huge money-maker for Google: paid access (licensed through publishers) not only on a per-title basis, but to the whole collection – ?all the world’s books. Royalties could be distributed from subscription revenues in proportion to access. Each time a book is opened, a penny could drop in the cup of that publisher or author. By then a good reading device will almost certainly exist (more likely a next generation iPhone than a Kindle) and people may actually be reading books through this system, directly on the network. Google and Amazon will then in effect be the digital infrastructure for the publishing industry, perhaps even taking on what remains of the print market through on-demand services purveyed through their digital stores. What will publishers then be? Disembodied imprints, free-floating editorial organs, publicity directors…?

Recent attempts to develop their identities online through their own websites seem hopelessly misguided. A publisher’s website is like their office building. Unless you have some direct stake in the industry, there’s little reason to bother know where it is. Readers are interested in books not publishers. They go to a bookseller, on foot or online, and they certainly don’t browse by publisher. Who really pays attention to who publishes the books they read anyway, especially in this corporatized era where the difference between imprints is increasingly cosmetic, like the range of brands, from dish soap to potato chips, under Proctor & Gamble’s aegis? The digital storefront model needs serious rethinking.

The future of distribution channels (Googlezon) is ultimately less interesting than this last question of identity. How will today’s publishers establish and maintain their authority as filterers and curators of the electronic word? Will they learn how to develop and nurture literate communities on the social Web? Will they be able to carry their distinguished imprints into a new terrain that operates under entirely different rules? So far, the legacy publishers have proved unable to grasp the way these things work in the new network culture and in the long run this could mean their downfall as nascent online communities (blog networks, webzines, political groups, activist networks, research portals, social media sites, list-servers, libraries, art collectives) emerge as the new imprints: publishing, filtering and linking in various forms and time signatures (books being only one) to highly activated, focused readerships.

The prospect of atomization here (a million publishing tribes and sub-tribes) is no doubt troubling, but the thought of renewed diversity in publishing after decades of shrinking horizons through corporate consolidation is just as, if not more, exciting. But the question of a mass audience does linger, and perhaps this is how certain of today’s publishers will survive, as the purveyors of mass market fare. But with digital distribution and print on demand, the economies of scale rationale for big publishers’ existence takes a big hit, and with self-publishing services like Amazon CreateSpace and Lulu.com, and the emergence of more accessible authoring tools like Sophie (still a ways away, but coming along), traditional publishers’ services (designing, packaging, distributing) are suddenly less special. What will really be important in a chaotic jumble of niche publishers are the critics, filterers and the context-generating communities that reliably draw attention to the things of value and link them meaningfully to the rest of the network. These can be big companies or light-weight garage operations that work on the back of third-party infrastructure like Google, Amazon, YouTube or whatever else. These will be the new publishers, or perhaps its more accurate to say, since publishing is now so trivial an act, the new editors.

Of course social filtering and tastemaking is what’s been happening on the Web for years, but over time it could actually supplant the publishing establishment as we currently know it, and not just the distribution channels, but the real heart of things: the imprimaturs, the filtering, the building of community. And I would guess that even as the digital business models sort themselves out (and it’s worth keeping an eye on interesting experiments like Content Syndicate, covered here yesterday, and on subscription and ad-based models), that there will be a great deal of free content flying around, publishers having finally come to realize (or having gone extinct with their old conceits) that controlling content is a lost cause and out of synch with the way info naturally circulates on the net. Increasingly it will be the filtering, curating, archiving, linking, commenting and community-building -? in other words, the network around the content -? that will be the thing of value. Expect Amazon and Google (Google, btw, having recently rolled out a bunch of impressive new social tools for Book Search, about which more soon) to move into this area in a big way.

Category Archives: amazon

national archives/amazon agreement released

From Rick Prelinger:

In a rapid FOIA response, NARA has released the partnership agreement between them and Amazon’s CustomFlix (now CreateSpace) subsidiary. It’s downloadable here (I’m responsible for the poorly derived PDF). I’ll be reading and analyzing it soon.

amazon on demand

CustomFlix, Amazon’s on-demand DVD distribution service, has just been rebranded as CreateSpace, and will now serve up self-published media of all types. Getting a title into the system is free and relatively simple. Books must be a minimum of 24 pages and have to be submitted as a PDF. Seven trim sizes are available for color interiors, five for black and white. Each title automatically receives an ISBN and is displayed to shoppers as “in stock,” available for shipping immediately. You set the list price on your media, Amazon sets the selling price. CreateSpace is listed as the publisher of the book unless you provide your own ISBN, in which case you can appear under your own imprint.

CreateSpace titles apparently are eligible for the SearchInside browsing program (I wonder what the threshhold, or price, for entry is). I assume they will also be open for reader reviews, ratings and such. One thing I’d be very curious to know, however, is whether, or to what extent, CreateSpace titles will get factored into the social filtering and recommendation engines that power Amazon’s browsing experience. In some ways, that would be the best indicator of how much this move will blur the lines – ?in the perceptions of readers – ?between traditional publishing and the new, less authoritative POD channels.

Obviously, this presents a major challenge to other on-demand services like iUniverse, Xlibris and Lulu. It will be interesting to observe how the publishing cultures on these sites will differ. Lulu.com seems to hold the most potential for the emergence of a new ecosystem of independent imprints and publishing storefronts, with the Lulu brand receding into a more infrastructural role. iUniverse and Xlibris still feel more like good old-fashioned vanity presses. Amazon theoretically offers good exposure for self-published authors, but again, as I queried above w/r/t social filtering, will CreateSpace titles be ghetto-ized in an Amazon sub-space or fully integrated into the world of books?

privatizing public goods (our tax dollars at work)

The National Archives is at it again. After announcing in January its exclusive agreement with Footnote.com to digitize and offer priced access to millions of public domain historical records, NARA (National Archives and Records Administration) has now inked a deal with Amazon to distribute significant parts of its vast archival films collection commercially on DVD and online.

As reported by the Cumberland Times News:

The arrangement allows Amazon – and a subsidiary, CustomFlix Labs Inc. – to copy National Archives films and video onto DVDs, and sell them to the public via the Internet.

The Archives will initially make available its collection of Universal Newsreels, dating from 1920 to 1967. Thousands of other public-domain and government films will be made available later.

Included in the initial offerings are events as diverse as the famous 1959 “Kitchen Debate” between then-Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, and footage of a youthful Fidel Castro after the communist revolution in Cuba. Newsreels that will become available later include coverage of the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the end of World War II, and the royal wedding of Princess Margaret.

National Archives officials said the arrangement will greatly expand the availability of the collection. Previously, such films could only be viewed and recorded at the Archives facility in College Park.

No doubt NARA should doing everything in its power to digitize and increase access to its vaults, but locking materials down through commercial partnerships is no way to run a public trust. In a more commendable move, NARA put up a draft of another digitization/distribution agreement it has in the works, this one with the Genealogical Society of Utah (GSU), and they’ve even opened it up to public comment. They ought to do the same with the Amazon deal, and while they’re at it, offer less antiquated mechanisms for the public to make their voices heard. As it stands, comments on the GSU draft can be submitted in the following ways:

* regulations.gov

* fax

* postal mail

* hand delivery or courier

Hey, why not use CommentPress?

visual amazon browser

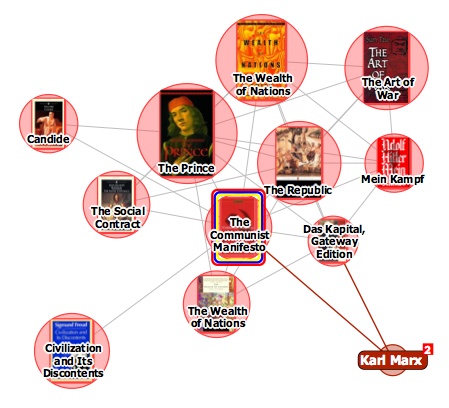

The interface design firm TouchGraph recently released a free visual browsing tool for Amazon’s books, movies, music and electronics inventories. My first thought was, aha, here’s a tool that can generate an image of Bob’s thought experiment, which reimagines The Communist Manifesto as a networked book, connected digitally to all the writings it has influenced and all the commentaries that have been written about it. Alas no.

It turns out that relations between items in the TouchGraph clusters are based not on citations across texts but purely on customer purchase patterns, the data that generates the “customers who bought this item also bought” links on Amazon pages. The results, consequently, are a tad shallow. Above you see The Communist Manifesto situated in a small web of political philosophy heavyweights, an image that reveals more about Amazon’s algorithmically derived recommendations than any actual networks of discourse.

TouchGraph has built a nice tool, and I’m sure with further investigation it might reveal interesting patterns in Amazon reading (and buying) behaviors (in the electronics category, it could also come in handy for comparison shopping). But I’d like to see a new verion that factors in citation indexes for books – data that Amazon already provides for many of its titles anyway. They could also look at user-supplied tags, Listmania lists, references from reader reviews etc. And perhaps with the option to view clusters across media types, not simply broken down into book, movie and music categories.

amazon starts to close the loop

About two and a half years ago, when the institute was first developing the idea of the “networked book,” we started a thought experiment which tries to imagine what would happen if Marx and Engels published the Communist Manifesto today and posted it to the web in a form which captured the extensive “conversation” that the essay provoked. About a year ago i made an image for a talk which cobbled together thumbnails from various books on Amazon which were related to the Communist Manifesto:

The point of the image was that these books, which are a concrete manifestation of the conversation, exist as isolated islands which at best can reference each other but which are not connected in the way we might imagine in the networked world being born.

Well, amidst all the discussion of the pluses and minuses of both Google and Microsoft book search, for the past two years Amazon has been quietly doing something exciting.

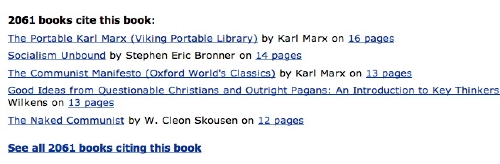

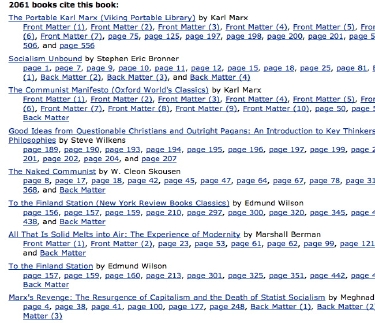

If you go to the Amazon page for an edition of the Communist Manifesto, you’ll see a reference to 2061 books in Amazon’s list which reference the Manifesto with a hot-link to each reference in each of the books.

The only big missing piece is an interactive semantic map with links between all 2061 books.

pre-order Gamer Theory on amazon!

Yes, it’s coming. The official pub date is April 15, 2007 from Harvard University Press, and the Institute will be producing a new online edition in conjunction with the print release. Pre-order now!

You’ll notice Ken’s dropped the L33T for the print title. He explains in a recent interview in RealTime:

For the website version I put the title in L33T [leet or gaming speak], partly in tribute to the early MUDs, but also to have a unique search string to put in Google or Technorati to track who was talking about it and where.

Smart. Also in that piece, a nice description of what we did:

As a critical engagement with the concepts of authorship, writing and intellectual property, GAM3R 7H30RY is a book written out of the social software fabric of blogs and wikis, Flickr, YouTube, Wikipedia and CiteULike. In other words, it represents a new writing practice that actively decentralizes the text as an object and disseminates it as an ongoing multi-channel conversation.

phony bookstore

Since it’s trash the ebooks week here at if:book, I thought I’d point out one more little item to round out our negative report card on the new Sony Reader. ![]() In a Business Week piece, amusingly titled “Gutenberg 1, Sony 0,” Stephen Wildstrom delivers another less than favorable review of Sony’s device and then really turns up the heat in his critique of their content portal, the Connect ebook store:

In a Business Week piece, amusingly titled “Gutenberg 1, Sony 0,” Stephen Wildstrom delivers another less than favorable review of Sony’s device and then really turns up the heat in his critique of their content portal, the Connect ebook store:

These deficits, however, pale compared to Sony’s Connect bookstore, which seems to be the work of someone who has never visited Amazon.com. Sony offers 10,000 titles, but that doesn’t mean you will find what you want. For example, only four of the top 10 titles on the Oct. 1 New York Times paperback best-seller list showed up. On the other hand, many books are priced below their print equivalents–most $7.99 paperbacks go for $6.39–and can be shared among any combination of three Readers or pcs, much as Apple iTunes allows multiple devices to share songs.

The worst problem is that search, the essence of an online bookstore, is broken. An author search for Dan Brown turned up 84 books, three of them by Dan Brown, the rest by people named Dan or Brown, or sometimes neither. Putting a search term in quotes should limit the results to those where the exact phrase occurs, but at the Sony store, it produced chaos. “Dan Brown” yielded 500 titles, mostly by people named neither Dan nor Brown. And the store doesn’t provide suggestions for related titles, reviews, previews–all those little extras that make Amazon great.

Remember that you can’t search texts at all on the actual Reader, though Sony does let you search books that you’ve purchased within your personal library in the Connect Store. But it’s a simple find function, bumping you from instance to instance, with nothing even approaching the sophisticated concordances and textual statistics that Amazon offers in Search Inside. You feel the whole time that you’re looking through the wrong end of the telescope. Such a total contraction of the possibilities of books. So little consideration of the complex ways readers interact with texts, or of the new directions that digital and networked interaction might open up.

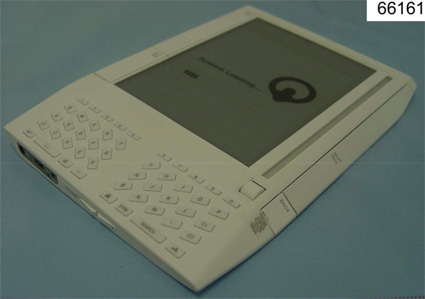

amazon looks to “kindle” appetite for ebooks with new device

Engadget has uncovered details about a soon-to-be-released upcoming/old/bogus(?) Amazon ebook reading device called the “Kindle,” which appears to have an e-ink display, and will presumably compete with the Sony Reader. From the basic specs they’ve posted, it looks like Kindle wins: it’s got more memory, it’s got a keyboard, and it can connect to the network (update: though only through the EV-DO wireless standard, which connects Blackberries and some cellphones; in other words, no basic wifi). This is all assuming that the thing actually exists, which we can’t verify.

Regardless, it seems the history of specialized ebook devices is doomed to repeat itself. Better displays (and e-ink is still a few years away from being really good) and more sophisticated content delivery won’t, in my opinion, make these machines much more successful than their discontinued forebears like the Gemstar or the eBookMan.

Ebooks, at least the kind Sony and Amazon will be selling, dwell in a no man’s land of misbegotten media forms: pale simulations of print that harness few of the possibilities of the digital (apparently, the Sony Reader won’t even have searchable text!). Add highly restrictive DRM and vendor lock-in through the proprietary formats and vendor sites made for these devices and you’ve got something truly depressing.

Publishers need to get out of this rut. The future is in networked text, multimedia and print on demand. Ebooks and their specialized hardware are a red herring.

Teleread also comments.

the future of media companies

Every day we hear more reports about how media / hardware/ distribution companies are ever more frequently expanding horizontally (going into new categories) as well as vertically (going into more parts of their production/distribution chain).

In that, Amazon launched a download video service. MySpace opens a music store to compete with Apple’s iTunes and is also considering the creation of a print magazine. HarperCollins is selling downloadable media on their website. These are just a few examples.

What will the future of media publishing look like? How close are we from having only a few multi-national companies that produce the hardware, media and distribution? What are the other options?

Could the pendulum ever swing the other way? Could the future branded media company outsource all the creative, technology, publishing and distribution in a similar way that a laptop manufacturer has its mother board, processor, batteries, memory, drive, screen and advertising come from somewhere outside the company?