Despite numerous books and accolades, Douglas Rushkoff is pursuing a PhD at Utrecht University, and has recently begun work on his dissertation, which will argue that the media forms of the network age are biased toward collaborative production. As proof of concept, Rushkoff is contemplating doing what he calls an “open source dissertation.” This would entail either a wikified outline to be fleshed out by volunteers, or some kind of additive approach wherein Rushkoff’s original content would become nested within layers of material contributed by collaborators. The latter tactic was employed in Rushkoff’s 2002 novel, “Exit Strategy,” which is posed as a manuscript from the dot.com days unearthed 200 years into the future. Before publishing, Rushkoff invited readers to participate in a public annotation process, in which they could play the role of literary excavator and submit their own marginalia for inclusion in the book. One hundred of these reader-contributed “future” annotations (mostly elucidations of late-90s slang) eventually appeared in the final print edition.

Despite numerous books and accolades, Douglas Rushkoff is pursuing a PhD at Utrecht University, and has recently begun work on his dissertation, which will argue that the media forms of the network age are biased toward collaborative production. As proof of concept, Rushkoff is contemplating doing what he calls an “open source dissertation.” This would entail either a wikified outline to be fleshed out by volunteers, or some kind of additive approach wherein Rushkoff’s original content would become nested within layers of material contributed by collaborators. The latter tactic was employed in Rushkoff’s 2002 novel, “Exit Strategy,” which is posed as a manuscript from the dot.com days unearthed 200 years into the future. Before publishing, Rushkoff invited readers to participate in a public annotation process, in which they could play the role of literary excavator and submit their own marginalia for inclusion in the book. One hundred of these reader-contributed “future” annotations (mostly elucidations of late-90s slang) eventually appeared in the final print edition.

Writing a novel this way is one thing, but a doctoral thesis will likely not be granted as much license. While I suspect the Dutch are more amenable to new forms, only two born-digital dissertations have ever been accepted by American universities: the first, a hypertext work on the online fan culture of “Xena: Warrior Princess,” which was submitted by Christine Boese to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1998; the second, approved just this past year at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, was a thesis by Virginia Kuhn on multimedia literacy and pedagogy that involved substantial amounts of video and audio and was assembled in TK3. For well over a year, the Institute advocated for Virginia in the face of enormous institutional resistance. The eventual hard-won victory occasioned a big story (subscription required) in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

In these cases, the bone of contention was form (though legal concerns about the use of video and audio certainly contributed in Kuhn’s case): it’s still inordinately difficult to convince thesis review committees to accept anything that cannot be read, archived and pointed to on paper. A dissertation that requires a digital environment, whether to employ unconventional structures (e.g. hypertext) or to incorporate multiple media forms, in most cases will not even be considered unless you wish to turn your thesis defense into a full-blown crusade. Yet, as pitched as these battles have been, what Rushkoff is suggesting will undoubtedly be far more unsettling to even the most progressive of academic administrations. We’re no longer simply talking about the leveraging of new rhetorical forms and a gradual disentanglement of printed pulp from institutional warrants, we’re talking about a fundamental reorientation of authorship.

When Rushkoff tossed out the idea of a wikified dissertation on his blog last week, readers came back with some interesting comments. One asked, “So do all of the contributors get a PhD?”, which raises the tricky question of how to evaluate and accredit collaborative work. “Not that professors at real grad schools don’t have scores of uncredited students doing their work for them,” Rushkoff replied. “they do. But that’s accepted as the way the institution works. To practice this out in the open is an entirely different thing.”

Category Archives: academic

nature re-jiggers peer review

Nature, one of the most esteemed arbiters of scientific research, has initiated a major experiment that could, if successful, fundamentally alter the way it handles peer review, and, in the long run, redefine what it means to be a scholarly journal. From the editors:

…like any process, peer review requires occasional scrutiny and assessement. Has the Internet bought new opportunities for journals to manage peer review more imaginatively or by different means? Are there any systematic flaws in the process? Should the process be transparent or confidential? Is the journal even necessary, or could scientists manage the peer review process themselves?

Nature’s peer review process has been maintained, unchanged, for decades. We, the editors, believe that the process functions well, by and large. But, in the spirit of being open to considering alternative approaches, we are taking two initiatives: a web debate and a trial of a particular type of open peer review.

The trial will not displace Nature’s traditional confidential peer review process, but will complement it. From 5 June 2006, authors may opt to have their submitted manuscripts posted publicly for comment.

In a way, Nature’s peer review trial is nothing new. Since the early days of the Internet, the scientific community has been finding ways to share research outside of the official publishing channels — the World Wide Web was created at a particle physics lab in Switzerland for the purpose of facilitating exchange among scientists. Of more direct concern to journal editors are initiatives like PLoS (Public Library of Science), a nonprofit, open-access publishing network founded expressly to undercut the hegemony of subscription-only journals in the medical sciences. More relevant to the issue of peer review is a project like arXiv.org, a “preprint” server hosted at Cornell, where for a decade scientists have circulated working papers in physics, mathematics, computer science and quantitative biology. Increasingly, scientists are posting to arXiv before submitting to journals, either to get some feedback, or, out of a competitive impulse, to quickly attach their names to a hot idea while waiting for the much slower and non-transparent review process at the journals to unfold. Even journalists covering the sciences are turning more and more to these preprint sites to scoop the latest breakthroughs.

Nature has taken the arXiv model and situated it within a more traditional editorial structure. Abstracts of papers submitted into Nature’s open peer review are immediately posted in a blog, from which anyone can download a full copy. Comments may then be submitted by any scientist in a relevant field, provided that they submit their name and an institutional email address. Once approved by the editors, comments are posted on the site, with RSS feeds available for individual comment streams. This all takes place alongside Nature’s established peer review process, which, when completed for a particular paper, will mean a freeze on that paper’s comments in the open review. At the end of the three-month trial, Nature will evaluate the public comments and publish its conclusions about the experiment.

A watershed moment in the evolution of academic publishing or simply a token gesture in the face of unstoppable change? We’ll have to wait and see. Obviously, Nature’s editors have read the writing on the wall: grasped that the locus of scientific discourse is shifting from the pages of journals to a broader online conversation. In attempting this experiment, Nature is saying that it would like to host that conversation, and at the same time suggesting that there’s still a crucial role to be played by the editor, even if that role increasingly (as we’ve found with GAM3R 7H30RY) is that of moderator. The experiment’s success will ultimately hinge on how much the scientific community buys into this kind of moderated semi-openness, and on how much control Nature is really willing to cede to the community. As of this writing, there are only a few comments on the open papers.

Accompanying the peer review trial, Nature is hosting a “web debate” (actually, more of an essay series) that brings together prominent scientists and editors to publicly examine the various dimensions of peer review: what works, what doesn’t, and what might be changed to better harness new communication technologies. It’s sort of a peer review of peer review. Hopefully this will occasion some serious discussion, not just in the sciences, but across academia, of how the peer review process might be re-thought in the context of networks to better serve scholars and the public.

(This is particularly exciting news for the Institute, since we are currently working to effect similar change in the humanities. We’ll talk more about that soon.)

academic library explores tagging

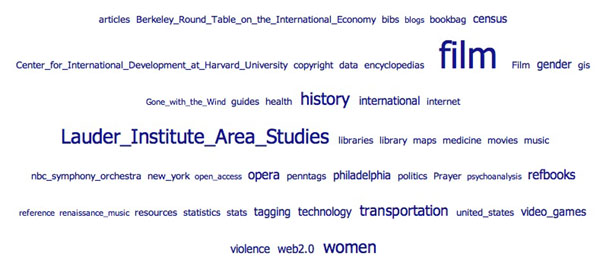

The ever-innovative University of Pennsylvania library is piloting a new social bookmarking system (like del.icio.us or CiteULike), in which the Penn community can tag resources and catalog items within its library system, as well as general sites from around the web. There’s also the option of grouping links thematically into “projects,” which reminds me of Amazon’s “listmania,” where readers compile public book lists on specific topics to guide other customers. It’s very exciting to see a library experimenting with folksonomies: exploring how top-down classification systems can productively collide with grassroots organization.

more evidence of academic publishing being broken

Stay Free! Daily reprints an article from the Wall Street Journal on how the editors of scientific journals published by Thomson Scientific are coercing authors to include more citations to articles published by Thomson Scientific:

Dr. West, the Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Physiology at the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, is one of the world’s leading authorities on respiratory physiology and was a member of Sir Edmund Hillary’s 1960 expedition to the Himalayas. After he submitted a paper on the design of the human lung to the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, an editor emailed him that the paper was basically fine. There was just one thing: Dr. West should cite more studies that had appeared in the respiratory journal.

If that seems like a surprising request, in the world of scientific publishing it no longer is. Scientists and editors say scientific journals increasingly are manipulating rankings — called “impact factors” — that are based on how often papers they publish are cited by other researchers.

“I was appalled,” says Dr. West of the request. “This was a clear abuse of the system because they were trying to rig their impact factor.”

Read the full article here.

post-doc fellowships available for work with the institute

The Institute for the Future of the Book is based at the Annenberg Center for Communication at USC. Jonathan Aronson, the executive director of the center, has just sent out a call for eight post-docs and one visiting scholar for next year. if you know of anyone who would like to apply, particularly people who would like to work with us at the institute, please pass this on. the institute’s activities at the center are described as follows:

Shifting Forms of Intellectual Discourse in a Networked Culture

For the past several hundred years intellectual discourse has been shaped by the rhythms and hierarchies inherent in the nature of print. As discourse shifts from page to screen, and more significantly to a networked environment, the old definitions and relations are undergoing unimagined changes. The shift in our world view from individual to network holds the promise of a radical reconfiguration in culture. Notions of authority are being challenged. The roles of author and reader are morphing and blurring. Publishing, methods of distribution, peer review and copyright — every crucial aspect of the way we move ideas around — is up for grabs. The new digital technologies afford vastly different outcomes ranging from oppressive to liberating. How we make this shift has critical long term implications for human society.

Research interests include: how reading and writing change in a networked culture; the changing role of copyright and fair use, the form and economics of open-source content, the shifting relationship of medium to message (or form to content).

if you have any questions, please feel free to email bob stein

blogging and the true spirit of peer review

Slate goes to college this week with a series of articles on higher education in America, among them a good piece by Robert S. Boynton that makes the case for academic blogging:

“…academic blogging represents the fruition, not a betrayal, of the university’s ideals. One might argue that blogging is in fact the very embodiment of what the political philosopher Michael Oakshott once called “The Conversation of Mankind”–an endless, thoroughly democratic dialogue about the best ideas and artifacts of our culture.

…might blogging be subversive precisely because it makes real the very vision of intellectual life that the university has never managed to achieve?”

The idea of blogging as a kind of service or outreach is just beginning (maybe) to gain traction. But what about blogging as scholarship? Most professor-bloggers I’ve spoken with consider blogging an invaluable tool for working through ideas, for facilitating exchange within and across disciplines. Some go so far as to say that it’s redefined their lives as academics. But don’t count on tenure committees to feel the same. Blogging is vaporous, they’ll inevitably point out. Not edited, mixing the personal and the professional. How can you maintain standards and the appropriate barriers to entry? Traditionally, peer review has served this gatekeeping function, but can there be a peer review system for blogs? And if so, would we want one?

Boynton has a few ideas about how something like this could work (we’re also wrestling with these questions on our back porch blog, Sidebar, with the eventual aim of making some sort of formal proposal). Whatever the technicalities, the approach should be to establish a middle path, something like peer review, but not a literal transposition. Some way to gauge and recognize the intellectual rigor of academic blogs without compromising their refreshing immediacy and individuality — without crashing the party as it were.

There’s already a sort of peer review going on among blog carnivals, the periodicals of the blogosphere. Carnivals are rotating showcases of exemplary blog writing in specific disciplines — history, philosophy, science, education, and many, many more, some quite eccentric. Like blogs, carnivals suffer from an unfortunate coinage. But even with a snootier name — blog symposiums maybe — you would never in a million years confuse them with an official-looking peer review journal. Yet the carnivals practice peer review in its most essential form: the gathering of one’s fellows (in this case academics and non-scholar enthusiasts alike) to collectively evaluate (ok, perhaps “savor” is more appropriate) a range of intellectual labors in a given area. Boynton:

In the end, peer review is just that: review by one’s peers. Any particular system should be judged by its efficiency and efficacy, and not by the perceived prestige of the publication in which the work appears.

If anything, blog-influenced practices like these might reclaim for intellectuals the true spirit of peer review, which, as Harvard University Press editor Lindsay Waters has argued, has been all but outsourced to prestigious university presses and journals. Experimenting with open-source methods of judgment–whether of straight scholarship or academic blogs–might actually revitalize academic writing.

It’s unfortunate that the accepted avenues of academic publishing — peer-reviewed journals and monographs — purchase prestige and job security usually at the expense of readership. It suggests an institutional bias in the academy against public intellectualism and in favor of kind of monastic seclusion (no doubt part of the legacy of this last great medieval institution). Nowhere is this more apparent than in the language of academic writing: opaque, convoluted, studded with jargon, its remoteness from ordinary human speech the surest sign of the author’s membership in the academic elite.

This crisis of clarity is paired with a crisis of opportunity, as severe financial pressures on university presses are reducing the number of options for professors to get published in the approved ways. What’s needed is an alternative outlet alongside traditional scholarly publishing, something between a casual, off-the-cuff web diary and a polished academic journal. Carnivals probably aren’t the solution, but something descended from them might well be.

It will be to the benefit of society if blogging can be claimed, sharpened and leveraged as a recognized scholarly practice, a way to merge the academy with the traffic of the real world. The university shouldn’t keep its talents locked up within a faltering publishing system that narrows rather than expands their scope. That’s not to say professors shouldn’t keep writing papers, books and monographs, shouldn’t continue to deepen the well of knowledge. On the contrary, blogging should be viewed only as a complement to research and teaching, not a replacement. But as such, it has the potential to breathe new life into the scholarly enterprise as a whole, just as Boynton describes.

Things move quickly — too quickly — in the media-saturated society. To remain vital, the academy needs to stick its neck out into the current, with the confidence that it won’t be swept away. What’s theory, after all, without practice? It’s always been publish or perish inside the academy, but these days on the outside, it’s more about self-publish. A small but growing group of academics have grasped this and are now in the process of inventing the future of their profession.

writing in the open

Mitch Stephens, NYU professor, was here for lunch today. when Ben and I met with him about a month ago about the academic bloggers/public intellectuals project, Mitch mentioned he had just signed a contract with Carroll & Graf to write a book on the history of atheism. today’s lunch was to follow up a suggestion we made that he might consider starting a blog to parallel the research and writing of the book. i’m delighted to report that Mitch has enthusiastically taken up the idea. sometime in the next few weeks we’ll launch a new blog, tentatively called Only Sky (shortened from the lyric of john lennon’s Imagine “. . . Above us only sky”). it will be an experiment to see whether blogging can be useful to the process of writing a book. i expect Mitch will be thinking out loud and asking all sorts of interesting questions. i also think that readers will likely provide important insight as well as ask their own fascinating questions which will in turn suggest fruitful directions of inquiry. stay tuned.

chicago law faculty starts blogging

Law professors at the University of Chicago have launched an experimental faculty blog to connect with students, the legal community, and the world at large. They’ve chosen a good moment to jump into the public sphere, when the Supreme Court is in flux. I wouldn’t be surprised if this spurred similar developments at other universities.

The University of Chicago School of Law has always been a place about ideas. We love talking about them, writing about them, and refining them through open, often lively conversation. This blog is just a natural extension of that tradition. Our hope is to use the blog as a forum in which to exchange nascent ideas with each other and also a wider audience, and to hear feedback about which ideas are compelling and which could use some re-tooling.

Though a growing number of scholars have embraced blogging, the academy as a whole has been loathe to take treat it as anything more than a dalliance. But a few more high profile moves like the one in Chicago and university boards may start clamoring to jump in. Perhaps then there can begin a serious discussion about legitimizing blogging as a form of scholarly production, and even as a kind of peer review. It’s not that all academics should be expected (or should want) to become high-profile public intellectuals. Fundamentally, academic blogging should be considered as an extension of “office hours,” a way to extend the dialogue with students and other faculty.

But there’s a definite benefit for the public when authoritative voices start blogging about what they know best. It’s refreshing to read sober, deeply informed reflections on the Miers nomination and surrounding questions of judicial philosophy written by people who know what they’re talking about. It helps us to parse the news and to tune out some of the more worthless punditry that goes on, both in mainstream media and in the blogosphere. Less noise, more signal.

Of course, experts can get noisy too. I was thrilled when Paul Krugman began writing his column for the NY Times — here was someone with a deep grasp of economics and a talent for explaining it in a political context. But as Krugman’s audience has grown, so has his propensity to blow off partisan steam. To me at least, his value as a public intellect has waned.

the blog carnival

The Chronicle of Higher Education ran a good piece last week by Henry Farrell — “The Blogosphere As A Carnival of Ideas” — looking at the small but growing minority of scholars who have become bloggers. Farrell is a poli sci professor at George Washington, and a contributor to the popular group blog Crooked Timber. He argues from experience how blogs have invigorated scholarly exchange within and across fields, allowing for a more relaxed discourse, free of the jargon and stuffy manner of journals. In some cases, blogs have enabled previously obscure academics to break beyond the ivory tower to connect with a large general readership hungry for their insight and expertise.

What Farrell neglects to mention — which is surprising given the title of the piece — is the phenomenon of the “blog carnival,” an interesting subculture of the web that has been adopted in certain academic, or quasi-academic, circles. A blog carnival is like a roving journal, a rotating showcase of interesting writing from around the blogosphere within a particular discipline. Individual bloggers volunteer to host a carnival on their personal blog, acting as chief editor for that edition. It falls to them to collect noteworthy items, and to sort through suggestions from the community, many of which are direct submissions from authors. On the appointed date (carnivals generally keep to a regular schedule) the carnival gets published and the community is treated to a richly annotated feast of new writing in the field.

Granted, not all participating bloggers are academics. Some are students, some simply enthusiasts. Anyone with a serious interest in the given area is usually welcome. Among the more active blog carnivals are Tangled Bank, a science carnival currently in its 38th edition, the Philosophers’ Carnival, whose 20th edition was just posted this past Sunday, and the History Carnival, currently in its 17th edition.

Here’s a small taste from the most recent offering at History Carnival, hosted by The Apocalyptic Historian:

New Deal liberalism has been on the minds of politicians lately. Hiram Hover posts about the recent talk of New Deal analogies from politicians in deciding how to help the victims of Katrina in “Responding to Katrina: Is History Any Guide?” Caleb McDaniel at Mode for Caleb draws a startling historical parallel between the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Phildelphia and New Orleans after Katrina in 2005.

In a comparison of another of Bush’s crises in the making, Jim MacDonald revisits the history of the Sepoy Rebellion with comments on the current situation in Iraq. Meanwhile Sepoy contributes to a recent attempt to compile the views Westerners have about Islam at Chapati Mystery.

How many times have humans believed the world was coming to an end? Natalie Bennett reviews a recent work on the Anabaptist takeover of Münster in 1534, when the belief in the impending apocalypse sent that city into chaos.

Most carnivals have a central site that indexes links to past editions and provides a schedule of upcoming ones, but the posts themselves exist on the various blogs that comprise the community. Hence the “carnival” — a traveling festival of ideas, a party that moves from house to house. Participating blogs generally display a badge on their sidebar signaling their affiliation with a particular collective.

Though carnivals keep to a strict schedule, there is no mandated format or style. Host bloggers can organize the material however they choose, putting their own personal spin or filter on the current round — just as long as they stick to the overall topic. The latest issue of Carnivalesque, a monthly circuit on medieval and early modern history, shows how far some hosts will go — styled as a full magazine, the October issue is complete with a mock cover, a letter from the editor, and links organized by section.

Though carnivals keep to a strict schedule, there is no mandated format or style. Host bloggers can organize the material however they choose, putting their own personal spin or filter on the current round — just as long as they stick to the overall topic. The latest issue of Carnivalesque, a monthly circuit on medieval and early modern history, shows how far some hosts will go — styled as a full magazine, the October issue is complete with a mock cover, a letter from the editor, and links organized by section.

The concept of the carnival seems to have originated in 2002 with “The Carnival of the Vanities,” which for a while served as a venue for bloggers to promote their best writing — a way of fighting the swift sinking of words in a sea of rapidly updating blogs. It’s not surprising that the idea was then taken up by academic types, since the carnival model, in its essence, rather jives with the main warranting mechanism of all scholarly publication: peer review. It’s a looser, less formal peer review to be sure, but still operates according to the ethos of the self-evaluating collective.

It’s worth paying attention to how these carnivals work because they provide at least part of the answer to a larger concern about the web: how to maintain quality and authority in a flood of amateur self-publishing. In the cycle of the carnival, blogging becomes a kind of open application process where your best work is dangled in the path of roving editors. You might say all bloggers are roving editors, but these ones represent an authoritative collective, one with a self-sustaining focus.

So the idea of the carnival, refined and sharpened by academics and lifelong learners, might in fact have broader application for electronic publishing. It happily incorporates the de-centralized nature of the web, thriving through collaborative labor, and yet it retains the primacy of individual voices and editorial sensibilities. Again, you might point out that its formula is far from unique, that this is in fact the procedure of just about any blog: find interesting stuff on the web and link to it with a few original comments. But the carnival focuses this practice into a regular, more durable form, providing an authoritative context that can be counted on week after week, even year after year. Sounds sort of like a magazine doesn’t it? But its offices are constantly in flux, its editorial chair a rotating one. I’m interested to see how it evolves. If blogs in cyberspace are like the single-cell organism in the primordial porridge, might the carnival be a form of multi-cell life?

directory of open access journals

The Directory of Open Access Journals indexes free peer review research journals from any country in any discipline. The directory is funded by the Soros “Open Access Initiative” which seeks to make the fruits of academic research freely available on the internet.

We define open access journals as journals that use a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. From the BOAI, Budapest Open Access Initiative, definition of “open access” we take the right of “users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles” as mandatory for a journal to be included in the directory. The journal should offer open access to their content without delay. Free user registration online is accepted.

(via librarian.net)