Bob will be appearing online at the Chronicle of Higher Education site for a live chat with readers about our recent cover story. The topic: “conversational scholarship.” 12 noon E.S.T.

UPDATE: you can now read a transcript of the chat here (same as the live link).

Category Archives: academic

MediaCommons 2: renewed publics, revised pedagogies

What a week it has been since Kathleen first posted about the MediaCommons project we are developing at the Institute for the Future of the Book. The responses we’ve received so far have mostly been both exciting and constructive and they clearly point to a community out there hungry for a digital scholarly network providing new opportunities for interaction and new modes of scholarship, pedagogy and community building.

As a co-creator with Christopher Lucas of Flow: A critical forum on television and media culture, an online journal intended to foster accessible and relevant conversations amongst media scholars and non-academic communities, I have seen first-hand the positive impact that more fluid exchanges of ideas can have on media studies scholarship. Flow’s mission is to provide a space where researchers, teachers, students, and the public can read about and discuss the changing landscape of contemporary media at the speed that media moves. Flow is organized around short, topical columns written by respected media scholars on a bi-weekly schedule. These columns invite response from the critical community by asking provocative questions that are significant to the study and experience of media.

The journal has been put to use in various classroom environments as well, with students either responding to pieces online or the inclusion of various columns in course packets, though this aspect of Flow’s mission has never achieved it’s fullest potential. Moreover, while the journal has been a phenomenal success amongst media studies scholars, it has largely failed to attract other constituencies on a consistent basis or engage them in critical conversations about media. My involvement with MediaCommons emerges out of a desire to make these scholarly conversations relevant to other constituencies — whether they be media producers, legislators, lobbyists, activists, students, or informed consumers — re-establishing the role of the academic as public intellectual and steward or critical conversations.

Today, I am going to write a little bit more about the pedagogical and community outreach goals of the site. These ideas are still being developed and we are hopeful that readers will chime in with other possibilities and suggestions as well. While I will discuss each of these subjects separately, one of the exciting opportunities with MediaCommons would be the integration of scholarly discourse, pedagogy, and community outreach in symbiotic ways.

cover story in chronicle of higher ed.

Which focuses primarily on GAM3R 7H30RY and MediaCommons, and implications for the future of scholarly discourse. There are substantial interview sections with McKenzie Wark and Kathleen Fitzpatrick. We’re excited.

Check it out:

– Chronicle subscribers

– Open URL

initial responses to MediaCommons

…have been quite encouraging. In addition to a very active and thought-provoking thread here on if:book, much has been blogged around the web over the past 48 hours. I’m glad to see that most of the responses around the web have zeroed in on the most crucial elements of our proposal, namely the reconfiguration of scholarly publishing into an open, process-oriented model, a fundamental re-thinking of peer review, and the goal of forging stronger communication between the academy and the publics it claims to serve. To a great extent, this can be credited to Kathleen’s elegant and lucid presentation the various pieces of this complex network we hope to create (several of which will be fleshed out in a post by Avi Santo this coming Monday). Following are selections from some of the particularly thoughtful and/or challenging posts.

Many are excited/intrigued by how MediaCommons will challenge what is traditionally accepted as scholarship:

In Ars Technica, “Breaking paper’s stranglehold on the academy“:

…what’s interesting about MediaCommons is the creators’ plan to make the site “count” among other academics. Peer review will be incorporated into most of the projects with the goal of giving the site the same cachet that print journals currently enjoy.

[…]

While many MediaCommons projects replicate existing academic models, others break new ground. Will contributing to a wiki someday secure a lifetime Harvard professorship? Stranger things have happened. The humanities has been wedded to an individualist research model for centuries; even working on collaborative projects often means going off and working alone on particular sections. Giving credit for collaboratively-constructed wikis, no matter how good they are, might be tricky when there are hundreds of authors. How would a tenure committee judge a person’s contributions?

And here’s librarian blogger Kris Grice, “Blogging for tenure?“:

…the more interesting thrust of the article, in my opinion, is the quite excellent point that open access systems won’t work unless the people who might be contributing have some sort of motivation to spend vast amounts of time and energy on publishing to the Web. To this end, the author suggests pushing to have participation in wikis, blogs, and forums count for tenure.

[…]

If you’re out there writing a blog or adding to a library wiki or doing volunteer reference through IRC or chat or IM, I’d strongly suggest you note URLs and take screenshots of your work. I am of the firm opinion that these activities count as “service to the profession” as much as attending conferences do– especially if you blog the conferences!

A bunch of articles characterize MediaCommons as a scholarly take on Wikipedia, which is interesting/cool/a little scary:

The Chronicle of Higher Education’s Wired Campus Blog, “Academics Start Their Own Wikipedia For Media Studies“:

MediaCommons will try a variety of new ideas to shake up scholarly publishing. One of them is essentially a mini-Wikipedia about aspects of the discipline.

And in ZD Net Education:

The model is somewhat like a Wikipedia for scholars. The hope is that contributions would be made by members which would eventually lead to tenure and promotion lending the project solid academic scholarship.

Now here’s Chuck Tryon, at The Chutry Experiment, on connecting scholars to a broader public:

I think I’m most enthusiastic about this project…because it focuses on the possibilities of allowing academics to write for audiences of non-academics and strives to use the network model to connect scholars who might otherwise read each other in isolation.

[…]

My initial enthusiasm for blogging grew out of a desire to write for audiences wider than my academic colleagues, and I think this is one of many arenas where MediaCommons can provide a valuable service. In addition to writing for this wider audience, I have met a number of media studies scholars, filmmakers, and other friends, and my thinking about film and media has been shaped by our conversations.

(As I’ve mentioned before, MediaCommons grew out of an initial inquiry into academic blogging as an emergent form of public intellectualism.)

A little more jaded, but still enthusiastic, is Anne Galloway at purse lip square jaw:

I think this is a great idea, although I confess to wishing we were finally beyond the point where we feel compelled to place the burden on academics to prove our worthiness. Don’t get me wrong – I believe that academic elitism is problematic and I think that traditional academic publishing is crippled by all sorts of internal and external constraints. I also think that something like MediaCommons offers a brilliant complement and challenge to both these practices. But if we are truly committed to greater reciprocity, then we also need to pay close attention to what is being given and taken. I started blogging in 2001 so that I could participate in exactly these kinds of scholarly/non-scholarly networks, and one of the things I’ve learned is that the give-and-take has never been equal, and only sometimes has it been equitable. I doubt that this or any other technologically-mediated network will put an end to anti-intellectualism from the right or the left, but I’m all for seeing what kinds of new connections we can forge together.

A few warn of the difficulties of building intellectual communities on the web:

Noah Wardrip-Fruin at Grand Text Auto (and also in a comment here on if:book):

I think the real trick here is going to be how they build the network. I suspect a dedicated community needs to be built before the first ambitious new project starts, and that this community is probably best constructed out of people who already have online scholarly lives to which they’re dedicated. Such people are less likely to flake, it seems to me, if they commit. But will they want to experiment with MediaCommons, given they’re already happy with their current activity? Or, can their current activity, aggregated, become the foundation of MediaCommons in a way that’s both relatively painless and clearly shows benefit? It’s an exciting and daunting road the Institute folks have mapped out for themselves, and I’m rooting for their success.

And Charlie Lowe at Kairosnews:

From a theoretical standpoint, this is an exciting collection of ideas for a new scholarly community, and I wish if:book the best in building and promoting MediaCommons.

From a pragmatic standpoint, however, I would offer the following advice…. The “If We Build It, They Will Come” strategy of web community development is laudable, but often doomed to failure. There are many projects around the web which are inspired by great ideas, yet they fail. Installing and configuring a content management system website is the easy part. Creating content for the site and building a community of people who use it is much harder. I feel it is typically better to limit the scope of a project early on and create a smaller community space in which the project can grow, then add more to serve the community’s needs over time.

My personal favorite. Jeff Rice (of Wayne State) just posted a lovely little meditation on reading Richard Lanham’s The Economics of Attention, which weaves in MediaCommons toward the end. This makes me ask myself: are we trying to bring about a revolution in publishing, or are we trying to catalyze what Lanham calls “a revolution in expressive logic”?

My reading attention, indeed, has been drifting: through blogs and websites, through current events, through ideas for dinner, through reading: through Lanham, Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis, through Wood’s The Power of Maps, through Clark’s Natural Born Cyborgs, and now even through a novel, Perdido Street Station. I move in and out of these places with ease (hmmmm….interesting) and with difficulty (am I obligated to finish this book??). I move through the texts.

Which is how I am imagining my new project on Detroit – a movement through spaces. Which also could stand for a type of writing model akin to the MediaCommons idea (or within such an idea); a need for something other (not in place of) stand alone writings among academics (i.e. uploaded papers). I’m not attracted to the idea of another clearing house of papers put online – or put online faster than a print publication would allow for. I’d like a space to drift within, adding, reading, thinking about, commenting on as I move through the writings, as I read some and not others, as I sample and frament my way along. “We have been thinking about human communication in an incomplete and inadequate way,” Lanham writes. The question is not that we should replicate already existing apparatuses, but invent (or try to invent) new structures based on new logics.

There are also some indications that the MediaCommons concept could prove contagious in other humanities disciplines, specifically history:

Manan Ahmed in Cliopatria:

I cannot, of course, hide my enthusiasm for such a project but I would really urge those who care about academic futures to stop by if:book, read the post, the comments and share your thoughts. Don’t be alarmed by the media studies label – it will work just as well for historians.

And this brilliant comment to the above-linked Chronicle blog from Adrian Lopez Denis, a PhD candidate in Latin American history at UCLA, who outlines a highly innovative strategy for student essay-writing assignments, serving up much food for thought w/r/t the pedagogical elements of MediaCommons:

Small teams of students should be the main producers of course material and every class should operate as a workshop for the collective assemblage of copyright-free instructional tools. […] Each assignment would generate a handful of multimedia modular units that could be used as building blocks to assemble larger teaching resources. Under this principle, each cohort of students would inherit some course material from their predecessors and contribute to it by adding new units or perfecting what is already there. Courses could evolve, expand, or even branch out. Although centered on the modular production of textbooks and anthologies, this concept could be extended to the creation of syllabi, handouts, slideshows, quizzes, webcasts, and much more. Educators would be involved in helping students to improve their writing rather than simply using the essays to gauge their individual performance. Students would be encouraged to collaborate rather than to compete, and could learn valuable lessons regarding the real nature and ultimate purpose of academic writing and scholarly research.

(Networked pedagogies are only briefly alluded to in Kathleen’s introductory essay. This, and community outreach, will be the focus of Avi’s post on Monday. Stay tuned.)

Other nice mentions from Teleread, Galleycat and I Am Dan.

introducing MediaCommons

UPDATE: Avi Santo’s follow-up post, “Renewed Publics, Revised Pedagogies”, is now up.

I’ve got the somewhat daunting pleasure of introducing the readers of if:book to one of the Institute’s projects-in-progress, MediaCommons.

As has been mentioned several times here, the Institute for the Future of the Book has spent much of 2006 exploring the future of electronic scholarly publishing and its many implications, including the development of alternate modes of peer-review and the possibilities for networked interaction amongst authors and texts. Over the course of the spring, we brainstormed, wrote a bunch of manifestos, and planned a meeting at which a group of primarily humanities-based scholars discussed the possibilities for a new model of academic publishing. Since that meeting, we’ve been working on a draft proposal for what we’re now thinking of as a wide-ranging scholarly network — an ecosystem, if you can bear that metaphor — in which folks working in media studies can write, publish, review, and discuss, in forms ranging from the blog to the monograph, from the purely textual to the multi-mediated, with all manner of degrees inbetween.

We decided to focus our efforts on the field of media studies for a number of reasons, some intellectual and some structural. On the intellectual side, scholars in media studies explore the very tools that a network such as the one we’re proposing will use, thus allowing for a productive self-reflexivity, leaving the network itself open to continual analysis and critique. Moreover, publishing within such a network seems increasingly crucial to media scholars, who need the ability to quote from the multi-mediated materials they write about, and for whom form needs to be able to follow content, allowing not just for writing about mediation but writing in a mediated environment. This connects to one of the key structural reasons for our choice: we’re convinced that media studies scholars will need to lead the way in convincing tenure and promotion committees that new modes of publishing like this network are not simply valid but important. As media scholars can make the “form must follow content” argument convincingly, and as tenure qualifications in media studies often include work done in media other than print already, we hope that media studies will provide a key point of entry for a broader reshaping of publishing in the humanities.

Our shift from thinking about an “electronic press” to thinking about a “scholarly network” came about gradually; the more we thought about the purposes behind electronic scholarly publishing, the more we became focused on the need not simply to provide better access to discrete scholarly texts but rather to reinvigorate intellectual discourse, and thus connections, amongst peers (and, not incidentally, discourse between the academy and the wider intellectual public). This need has grown for any number of systemic reasons, including the substantive and often debilitating time-lags between the completion of a piece of scholarly writing and its publication, as well as the subsequent delays between publication of the primary text and publication of any reviews or responses to that text. These time-lags have been worsened by the increasing economic difficulties threatening many university presses and libraries, which each year face new administrative and financial obstacles to producing, distributing, and making available the full range of publishable texts and ideas in development in any given field. The combination of such structural problems in academic publishing has resulted in an increasing disconnection among scholars, whose work requires a give-and-take with peers, and yet is produced in greater and greater isolation.

Such isolation is highlighted, of course, in thinking about the relationship between the academy and the rest of contemporary society. The financial crisis in scholarly publishing is of course not unrelated to the failure of most academic writing to find any audience outside the academy. While we wouldn’t want to suggest that all scholarly production ought to be accessible to non-specialists — there’s certainly a need for the kinds of communication amongst peers that wouldn’t be of interest to most mainstream readers — we do nonetheless believe that the lack of communication between the academy and the wider reading public points to a need to rethink the role of the academic in public intellectual life.

Most universities provide fairly structured definitions of the academic’s role, both as part of the institution’s mission and as informing the criteria under which faculty are hired and reviewed: the academic’s function is to conduct and communicate the products of research through publication, to disseminate knowledge through teaching, and to perform various kinds of service to communities ranging from the institution to the professional society to the wider public. Traditional modes of scholarly life tend to make these goals appear discrete, and they often take place in three very different discursive registers. Despite often being defined as a public good, in fact, much academic discourse remains inaccessible and impenetrable to the publics it seeks to serve.

We believe, however, that the goals of scholarship, teaching, and service are deeply intertwined, and that a reimagining of the scholarly press through the affordances of contemporary network technologies will enable us not simply to build a better publishing process but also to forge better relationships among colleagues, and between the academy and the public. The move from the discrete, proprietary, market-driven press to an open access scholarly network became in our conversations both a logical way of meeting the multiple mandates that academics operate within and a necessary intervention for the academy, allowing it to forge a more inclusive community of scholars who challenge opaque forms of traditional scholarship by foregrounding process and emphasizing critical dialogue. Such dialogue will foster new scholarship that operates in modes that are collaborative, interactive, multimediated, networked, nonlinear, and multi-accented. In the process, an open access scholarly network will also build bridges with diverse non-academic communities, allowing the academy to regain its credibility with these constituencies who have come to equate scholarly critical discourse with ivory tower elitism.

With that as preamble, let me attempt to describe what we’re currently imagining. Much of what follows is speculative; no doubt we’ll get into the development process and discover that some of our desires can’t immediately be met. We’ll also no doubt be inspired to add new resources that we can’t currently imagine. This indeterminacy is not a drawback, however, but instead one of the most tangible benefits of working within a digitally networked environment, which allows for a malleability and growth that makes such evolution not just possible but desirable.

At the moment, we imagine MediaCommons as a wide-ranging network with a relatively static point of entry that brings the participant into the MediaCommons community and makes apparent the wealth of different resources at his or her disposal. On this front page will be different modules highlighting what’s happening in various nodes (“today in the blogs”; active forum topics; “just posted” texts from journals; featured projects). One module on this front page might be made customizable (“My MediaCommons”), such that participants can in some fashion design their own interfaces with the network, tracking the conversations and texts in which they are most interested.

The various nodes in this network will support the publication and discussion of a wide variety of forms of scholarly writing. Those nodes may include:

— electronic “monographs” (Mackenzie Wark’s GAM3R 7H30RY is a key model here), which will allow editors and authors to work together in the development of ideas that surface in blogs and other discussions, as well as in the design, production, publicizing, and review of individual and collaborative projects;

— electronic “casebooks,” which will bring together writing by many authors on a single subject — a single television program, for instance — along with pedagogical and other materials, allowing the casebooks to serve as continually evolving textbooks;

— electronic “journals,” in which editors bring together article-length texts on a range of subjects that are somehow interrelated;

— electronic reference works, in which a community collectively produces, in a mode analogous to current wiki projects, authoritative resources for research in the field;

— electronic forums, including both threaded discussions and a wealth of blogs, through which a wide range of media scholars, practitioners, policy makers, and users are able to discuss media events and texts can be discussed in real time. These nodes will promote ongoing discourse and interconnection among readers and writers, and will allow for the germination and exploration of the ideas and arguments of more sustained pieces of scholarly writing.

Many other such possibilities are imaginable. The key elements that they share, made possible by digital technologies, are their interconnections and their openness for discussion and revision. These potentials will help scholars energize their lives as writers, as teachers, and as public intellectuals.

Such openness and interconnection will also allow us to make the process of scholarly work just as visible and valuable as its product; readers will be able to follow the development of an idea from its germination in a blog, though its drafting as an article, to its revisions, and authors will be able to work in dialogue with those readers, generating discussion and obtaining feedback on work-in-progress at many different stages. Because such discussions will take place in the open, and because the enormous time lags of the current modes of academic publishing will be greatly lessened, this ongoing discourse among authors and readers will no doubt result in the generation of many new ideas, leading to more exciting new work.

Moreover, because participants in the network will come from many different perspectives — not just faculty, but also students, independent scholars, media makers, journalists, critics, activists, and interested members of the broader public — MediaCommons will promote the integration of research, teaching, and service. The network will contain nodes that are specifically designed for the development of pedagogical materials, and for the interactions of faculty and students; the network will also promote community engagement by inviting the participation of grass-roots media activists and by fostering dialogue among authors and readers from many different constituencies. We’ll be posting in more depth about these pedagogical and community-outreach functions very soon.

We’re of course still in the process of designing how MediaCommons will function on a day-to-day basis. MediaCommons will be a membership-driven network; membership will be open to anyone interested, including writers and readers both within and outside the academy, and that membership have a great deal of influence over the directions in which the network develops. At the moment, we imagine that the network’s operations will be led by an editorial board composed of two senior/coordinating editors, who will have oversight over the network as a whole, and a number of area editors, who will have oversight over different nodes on the network (such as long-form projects, community-building, design, etc), helping to shepherd discussion and develop projects. The editorial board will have the responsibility for setting and implementing network policy, but will do so in dialogue with the general membership.

In addition to the editorial board, MediaCommons will also recruit a range of on-the-ground editors, who will for relatively brief periods of time take charge of various aspects of or projects on the network, doing work such as copyediting and design, fostering conversation, and participating actively in the network’s many discussion spaces.

MediaCommons will also, crucially, serve as a profound intervention into the processes of scholarly peer review, processes which (as I’ve gone on at length about on other occasions) are of enormous importance to the warranting and credentialing needs of the contemporary academy but which are, we feel, of only marginal value to scholars themselves. Our plan is to develop and employ a process of “peer-to-peer review,” in which texts are discussed and, in some sense, “ranked” by a committed community of readers. This new process will shift the purpose of such review from a gatekeeping function, determining whether or not a manuscript should be published, to one that instead determines how a text should be received. Peer-to-peer review will also focus on the development of authors and the deepening of ideas, rather than simply an up-or-down vote on any particular text.

How exactly this peer-to-peer review process will work is open to some discussion, as yet. The editorial board will develop a set of guidelines for determining which readers will be designated “peers,” and within which nodes of MediaCommons; these “peers” will then have the ability to review the texts posted in their nodes. The authors of those texts undergoing review will be encouraged to respond to the comments and criticisms of their peers, transforming a one-way process of critique into a multi-dimensional conversation.

Because this process will take place in public, we feel that certain rules of engagement will be important, including that authors must take the first step in requesting review of their work, such that the fear of a potentially damaging critique being levied at a text-in-process can be ameliorated; that peers must comment publicly, and must take responsibility for their critiques by attaching their names to them, creating an atmosphere of honest, thoughtful debate; that authors should have the ability to request review from particular member constituencies whose readings may be of most help to them; that authors must have the ability to withdraw texts that have received negative reviews from the network, in order that they might revise and resubmit; and that authors and peers alike must commit themselves to regular participation in the processes of peer-to-peer review. Peers need not necessarily be authors, but authors should always be peers, invested in the discussion of the work of others on the network.

There’s obviously much more to be written about this project; we’ll no doubt be elaborating on many of the points briefly sketched out here in the days to come. We’d love some feedback on our thoughts thus far; in order for this network to take off, we’ll need broad buy-in right from the outset. Please let us know what you like here, what you don’t, what other features you’d like us to consider, and any other thoughts you might have about how we might really forge the scholarly discourse network of the future.

UPDATE: Avi Santo’s follow-up post, “Renewed Publics, Revised Pedagogies”, is now up.

aggregator academica

Scott McLemee has made an interesting proposal for a scholarly aggregator site that would weave together material from academic blogs and university presses. Initially, this would resemble an enhanced academic blogroll, building on existing efforts such as those at Crooked Timber and Cliopatria, but McLemee envisions it eventually growing into a full-fledged discourse network, with book reviews, symposia, a specialized search engine, and a peer voting system á la Digg.

This all bears significant resemblance to some of the ideas that emerged from a small academic blogging symposium that the Institute held last November to brainstorm ways to leverage scholarly blogging, and to encourage more professors to step out of the confines of the academy into the role of public intellectual. Some of those ideas are set down here, on a blog we used for planning the meeting. Also take a look at John Holbo’s proposal for an academic blog collective, or co-op. Also note the various blog carnivals around the web, which practice a simple but effective form of community aggregation and review. One commenter on McLemee’s article points to a science blog aggregator site called Postgenomic, which offers a similar range of services, as well as providing useful meta-analysis of trends across the science blogosphere — i.e. what are the most discussed journal papers, news stories, and topics.

For any enterprise of this kind, where the goal is to pull together an enormous number of strands into a coherent whole, the role of the editor is crucial. Yet, at a time when self-publishing is the becoming the modus operandi for anyone who would seek to maintain a piece of intellectual turf in the network culture, the editor’s task is less to solicit or vet new work, and more to moderate the vast conversation that is already occurring — to listen to what the collective is saying, and also to draw connections that the collective, in their bloggers’ trenches, may have missed.

Since that November meeting, our thinking has broadened to include not just blogging, but all forms of academic publishing. On Monday, we’ll post an introduction to a project we’re cooking up for an online scholarly network in the field of media studies. Stay tuned.

rice university press reborn digital

After lying dormant for ten years, Rice University Press has relaunched, reconstituting itself as a fully digital operation centered around Connexions, an open-access repository of learning modules, course guides and authoring tools.  Connexions was started at Rice in 1999 by Richard Baraniuk, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and has since grown into one of the leading sources of open educational content — also an early mover into the Creative Commons movement, building flexible licensing into its publishing platform and allowing teachers and students to produce derivative materials and customized textbooks from the array of resources available on the site.

Connexions was started at Rice in 1999 by Richard Baraniuk, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and has since grown into one of the leading sources of open educational content — also an early mover into the Creative Commons movement, building flexible licensing into its publishing platform and allowing teachers and students to produce derivative materials and customized textbooks from the array of resources available on the site.

The new ingredient in this mix is a print-on-demand option through a company called QOOP. Students can order paper or hard-bound copies of learning modules for a fraction of the cost of commercial textbooks, even used ones. There are also some inexpensive download options. Web access, however, is free to all. Moreover, Connexions authors can update and amend their modules at all times. The project is billed as “open source” but individual authorship is still the main paradigm. The print-on-demand and for-pay download schemes may even generate small royalties for some authors.

The Wall Street Journal reports. You can also read these two press releases from Rice:

“Rice University Press reborn as nation’s first fully digital academic press”

“Print deal makes Connexions leading open-source publisher”

UPDATE:

Kathleen Fitzpatrick makes the point I didn’t have time to make when I posted this:

Rice plans, however, to “solicit and edit manuscripts the old-fashioned way,” which strikes me as a very cautious maneuver, one that suggests that the change of venue involved in moving the press online may not be enough to really revolutionize academic publishing. After all, if Rice UP was crushed by its financial losses last time around, can the same basic structure–except with far shorter print runs–save it this time out?

I’m excited to see what Rice produces, and quite hopeful that other university presses will follow in their footsteps. I still believe, however, that it’s going to take a much riskier, much more radical revisioning of what scholarly publishing is all about in order to keep such presses alive in the years to come.

GAM3R 7H30RY gets (open) peer-reviewed

Steven Shaviro (of Wayne State University) has written a terrific review of GAM3R 7H30RY on his blog, The Pinnochio Theory, enacting what can only be described as spontaneous, open peer review. This is the first major article to seriously engage with the ideas and arguments of the book itself, rather than the more general story of Wark’s experiment with open, collaborative publishing (for example, see here and here). Anyone looking for a good encapsulation of McKenzie’s ideas would do well to read this. Here, as a taste, is Shaviro’s explanation of “a world…made over as an imperfect copy of the game“:

Computer games clarify the inner logic of social control at work in the world. Games give an outline of what actually happens in much messier and less totalized ways. Thereby, however, games point up the ways in which social control is precisely directed towards creating game-like clarities and firm outlines, at the expense of our freedoms.

Now, I think it’s worth pointing out the one gap in this otherwise exceptional piece. That is that, while exhibiting acute insight into the book’s theoretical dimensions, Shaviro does not discuss the form in which these theories are delivered, apart from brief mention of the numbered paragraph scheme and the alphabetically ordered chapter titles. Though he does link to the website, at no point does he mention the open web format and the reader discussion areas, nor the fact that he read the book online, with the comments of readers sitting plainly in the margins. If you were to read only this review, you would assume Shaviro was referring to a vetted, published book from a university press, when actually he is discussing a networked book that is 1.1 — a.k.a. still in development. Shaviro treats the text as though it is fully cooked (naturally, this is how we are used to dealing with scholarly works). But what happens when there’s a GAM3R 7H30RY 1.2, or a 2.0? Will Shaviro’s review correspondingly update? Does an open-ended book require a more open-ended critique? This is not so much a criticism of Shaviro as an observation of a tricky problem yet to be solved.

Regardless, this a valuable contribution to the surrounding literature. It’s very exciting to see leading scholars building a discourse outside the conventional publishing channels: Wark, through his pre-publication with the Institute, and Shaviro with his unsolicited blog review. This is an excellent sign.

dark waters? scholarly presses tread along…

Recently in New Orleans, I was working at AAUP‘s annual meeting of university presses. At the opening banquet, Times-Picayune editor Jim Amoss brought a large audience of publishing folk through a blow-by-blow of New Orleans’ storm last fall. What I found particularly resonant in his recount, beyond his staff’s stamina in the face of “the big one”, was the Big Bang phenomena that occured in tandem with the flooding, instantly expanding the relationship between their print and internet editions.

Their print infrastructure wrecked, The Times-Picayune immediately turned to the internet to broadcast the crisis that was flooding in around them. Even the more troglodytic staffers familiarized themselves with blogging and online publishing. By the time some of their print had arrived from offsite and reporters were using it as currency to get through military checkpoints, their staff had adapted to web publishing technologies and now, Amoss told me, they all use it on a daily basis.

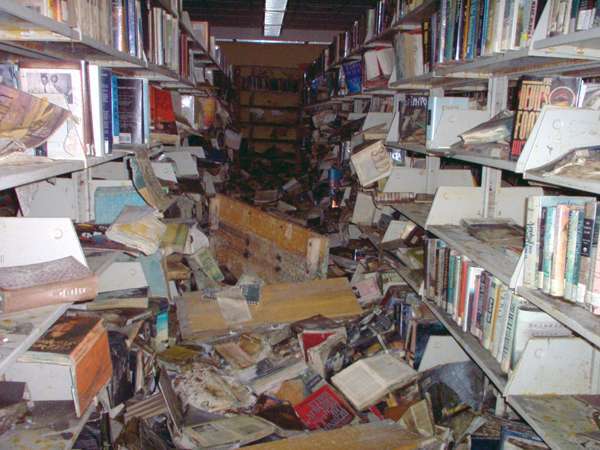

Martin Luther King Branch

If the Times-Picayune, a daily publication of considerable city-paper bulk, can adapt within a week to the web, what is taking university presses so long? Surely, we shouldn’t wait for a crisis of Noah’s Ark proportions to push academe to leap into the future present. What I think Amoss’s talk subtly arrived at was a reassessment of *crisis* for the constituency of scholarly publishing that sat before him.

“Part of the problem is that much of this new technology wasn’t developed within the publishing houses,” a director mentioned to me in response to my wonderings. “So there’s a general feeling of this technology pushing in on the presses from the outside.”

East New Orleans Regional Branch

But “general feeling” belies what were substantially disparate opinions among attendees. Frustration emanated from the more tech-adventurous on the failure of traditional and un-tech’d folks to “get with the program,” whereas those unschooled on wikis and Web 2.0 tried to wrap their brains around the publishing “crisis” as they saw it: outdating their business models, scrambling their workflow charts and threatening to render their print operations obsolete.

That said, cutting through this noise were some promising talks on developments. A handful of presses have established e-publishing initiatives, many of which were conceived of with their university libraries. By piggybacking on the techno-knowledge and skill of librarians who are already digitizing their collections and acquiring digital titles (librarians whose acquisitions budgets far surpass those of many university presses,) presses have brought forth inventive virtual nodes of scholarship. Interestingly, these joint digital endeavors often explore disciplines that now have difficulty making their way to print.

Some projects to look at:

MITH (Maryland); NINES (scholar driven open-access project); Martha Nell Smith’s Dickinson Electronic Archives Project; Rotunda (Virginia); DART (Columbia); Anthrosource (California: Their member portal has communities of interest establishing in various fields, which may evolve into new journals.)

East New Orleans Regional Branch

While the marriage of the university library and press serves to reify their shared mandate to disseminate scholarship, compatibility issues arise in the accessibility and custody of projects. Libraries would like content to be open, and university presses prefer to focus on revenue generating subscribership.

One Digital Publishing session shed light on more theoretical concerns of presses. As MLA reviews the tenure system, partly in response to the decline of monograph publication opportunities, some argued that the nature of the monograph (sustained argument and narrative) doesn’t lend itself well to online reading. But, as the monograph will stay, how do presses publish them economically?

Nora Navra Branch

On the peer review front, another concern critiqued the web’s predominantly fact-based interaction: “The web seems to be pushing us back from an emphasis on ideas and synthesis/analysis to focus on facts.”

Access to facts opens up opportunities for creative presentation of information, but scholarly presses are struggling with how interpretive work can be built on that digitally. A UVA respondant noted, “Librarians say people are looking for info on the web, but then moving to print for the interpretation; at Rotunda, the experience is that you have to put up the mass of information allowing the user to find the raw information, but what to do next is lacking online.”

Promising comments came from Peter Brantley (California Digital Library) on the journal side: peer review isn’t everything and avenues already exist to evaluate content and comment on work (linkages, citation analysis, etc.) To my relief, he suggested folks look at the Institute for the Future of the Book, who are exploring new forms of narrative and participatory material, and Nature’s experiments in peer review.

Sure, at this point, there lacks a concrete theoretical underpinning of how the Internet should provide information, and which kinds. But most of us view this flux as its strength. For university presses, crises arise when what scholar Martha Nell Smith dubs the “priestly voice” of scholarship and authoritative texts, is challenged. Fortifying against the evolution and burgeoning pluralism won’t work. Unstifled, collaborative exploration amongst a range of key players will reveal the possiblities of the terrain, and ease the press out of rising waters.

Robert E. Smith Regional Branch

All images from New Orleans Public Library

on the future of peer review in electronic scholarly publishing

Over the last several months, as I’ve met with the folks from if:book and with the quite impressive group of academics we pulled together to discuss the possibility of starting an all-electronic scholarly press, I’ve spent an awful lot of time thinking and talking about peer review — how it currently functions, why we need it, and how it might be improved. Peer review is extremely important — I want to acknowledge that right up front — but it threatens to become the axle around which all conversations about the future of publishing get wrapped, like Isadora Duncan’s scarf, strangling any possible innovations in scholarly communication before they can get launched. In order to move forward with any kind of innovative publishing process, we must solve the peer review problem, but in order to do so, we first have to separate the structure of peer review from the purposes it serves — and we need to be a bit brutally honest with ourselves about those purposes, distinguishing between those purposes we’d ideally like peer review to serve and those functions it actually winds up fulfilling.

The issue of peer review has of course been brought back to the front of my consciousness by the experiment with open peer review currently being undertaken by the journal Nature, as well as by the debate about the future of peer review that the journal is currently hosting (both introduced last week here on if:book). The experiment is fairly simple: the editors of Nature have created an online open review system that will run parallel to its traditional anonymous review process.

From 5 June 2006, authors may opt to have their submitted manuscripts posted publicly for comment.

Any scientist may then post comments, provided they identify themselves. Once the usual confidential peer review process is complete, the public ‘open peer review’ process will be closed. Editors will then read all comments on the manuscript and invite authors to respond. At the end of the process, as part of the trial, editors will assess the value of the public comments.

As several entries in the web debate that is running alongside this trial make clear, though, this is not exactly a groundbreaking model; the editors of several other scientific journals that already use open review systems to varying extents have posted brief comments about their processes. Electronic Transactions in Artificial Intelligence, for instance, has a two-stage process, a three-month open review stage, followed by a speedy up-or-down refereeing stage (with some time for revisions, if desired, inbetween). This process, the editors acknowledge, has produced some complications in the notion of “publication,” as the texts in the open review stage are already freely available online; in some sense, the journal itself has become a vehicle for re-publishing selected articles.

Peer review is, by this model, designed to serve two different purposes — first, fostering discussion and feedback amongst scholars, with the aim of strengthening the work that they produce; second, filtering that work for quality, such that only the best is selected for final “publication.” ETAI’s dual-stage process makes this bifurcation in the purpose of peer review clear, and manages to serve both functions well. Moreover, by foregrounding the open stage of peer review — by considering an article “published” during the three months of its open review, but then only “refereed” once anonymous scientists have held their up-or-down vote, a vote that comes only after the article has been read, discussed, and revised — this kind of process seems to return the center of gravity in peer review to communication amongst peers.

I wonder, then, about the relatively conservative move that Nature has made with its open peer review trial. First, the journal is at great pains to reassure authors and readers that traditional, anonymous peer review will still take place alongside open discussion. Beyond this, however, there seems to be a relative lack of communication between those two forms of review: open review will take place at the same time as anonymous review, rather than as a preliminary phase, preventing authors from putting the public comments they receive to use in revision; and while the editors will “read” all such public comments, it appears that only the anonymous reviews will be considered in determining whether any given article is published. Is this caution about open review an attempt to avoid throwing out the baby of quality control with the bathwater of anonymity? In fact, the editors of Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics present evidence (based on their two-stage review process) that open review significantly increases the quality of articles a journal publishes:

Our statistics confirm that collaborative peer review facilitates and enhances quality assurance. The journal has a relatively low overall rejection rate of less than 20%, but only three years after its launch the ISI journal impact factor ranked Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics twelfth out of 169 journals in ‘Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences’ and ‘Environmental Sciences’.

These numbers support the idea that public peer review and interactive discussion deter authors from submitting low-quality manuscripts, and thus relieve editors and reviewers from spending too much time on deficient submissions.

By keeping anonymous review and open review separate, without allowing the open any precedence, Nature is allowing itself to avoid asking any risky questions about the purposes of its process, and is perhaps inadvertently maintaining the focus on peer review’s gatekeeping function. The result of such a focus is that scholars are less able to learn from the review process, less able to put comments on their work to use, and less able to respond to those comments in kind.

If anonymous, closed peer review processes aren’t facilitating scholarly discourse, what purposes do they serve? Gatekeeping, as I’ve suggested, is a primary one; as almost all of the folks I’ve talked with this spring have insisted, peer review is necessary to ensuring that the work published by scholarly outlets is of sufficiently high quality, and anonymity is necessary in order to allow reviewers the freedom to say that an article should not be published. In fact, this question of anonymity is quite fraught for most of the academics with whom I’ve spoken; they have repeatedly responded with various degrees of alarm to suggestions that their review comments might in fact be more productive delivered publicly, as part of an ongoing conversation with the author, rather than as a backchannel, one-way communication mediated by an editor. Such a position may be justifiable if, again, the primary purpose of peer review is quality control, and if the process is reliably scrupulous. However, as other discussants in the Nature web debate point out, blind peer review is not a perfect process, subject as it is to all kinds of failures and abuses, ranging from flawed articles that nonetheless make it through the system to ideas that are appropriated by unethical reviewers, with all manner of cronyism and professional jealousy inbetween.

So, again, if closed peer review processes aren’t serving scholars in their need for feedback and discussion, and if they can’t be wholly relied upon for their quality-control functions, what’s left? I’d argue that the primary purpose that anonymous peer review actually serves today, at least in the humanities (and that qualifier, and everything that follows from it, opens a whole other can of worms that needs further discussion — what are the different needs with respect to peer review in the different disciplines?), is that of institutional warranting, of conveying to college and university administrations that the work their employees are doing is appropriate and well-thought-of in its field, and thus that these employees are deserving of ongoing appointments, tenure, promotions, raises, and whathaveyou.

Are these the functions that we really want peer review to serve? Vast amounts of scholars’ time is poured into the peer review process each year; wouldn’t it be better to put that time into open discussions that not only improve the individual texts under review but are also, potentially, productive of new work? Isn’t it possible that scholars would all be better served by separating the question of credentialing from the publishing process, by allowing everything through the gate, by designing a post-publication peer review process that focuses on how a scholarly text should be received rather than whether it should be out there in the first place? Would the various credentialing bodies that currently rely on peer review’s gatekeeping function be satisfied if we were to say to them, “no, anonymous reviewers did not determine whether my article was worthy of publication, but if you look at the comments that my article has received, you can see that ten of the top experts in my field had really positive, constructive things to say about it”?

Nature‘s experiment is an honorable one, and a step in the right direction. It is, however, a conservative step, one that foregrounds the institutional purposes of peer review rather than the ways that such review might be made to better serve the scholarly community. We’ve been working this spring on what we imagine to be a more progressive possibility, the scholarly press reimagined not as a disseminator of discrete electronic texts, but instead as a network that brings scholars together, allowing them to publish everything from blogs to books in formats that allow for productive connections, discussions, and discoveries. I’ll be writing more about this network soon; in the meantime, however, if we really want to energize scholarly discourse through this new mode of networked publishing, we’re going to have to design, from the ground up, a productive new peer review process, one that makes more fruitful interaction among authors and readers a primary goal.