This is a bilingual (English/Spanish) post. Spanish version can be found lower down.

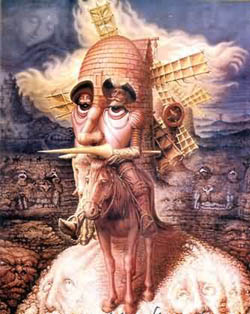

Santofile, uses “meme” to allude to creative freedom in the digital world. Meme is mimesis and is self-generating. It refers to mediation in the sense of remix and appropriation, to the mixing of works that circulate in the Internet in order to produce an original piece. Among Santofile’s projects is X_Reloaded, an interpretation of the first chapter of Don Quixote, compiled from disparate works inspired by the fourth centennial of its publication.

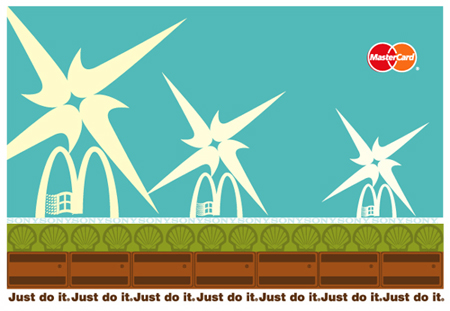

They put together such diverse creators as William Burroughs and Adbusters, whose common context is precisely the idea of busting. Busting decontextualizes a piece (work of art, advertisement, text) causing it to lose its character as a static icon by giving it a new life inside a new context.

To choose Don Quixote as the text for X_Reloaded, is an allusion to the concept of remix per excellence. Cervantes appropriated chivalry novels with the intention to subvert the genre, and his final remix, decontextualized, is a unique and original work. Printing itself in Cervantes’ times required a highly legible copy, which wasn’t necessarily the original manuscript. Thus, the “original” was a copy made by one or more amanuenses. And from this “original” corrected by the author, a sort of predecessor of proofreading, the book was put together by the typesetter, with its consequent errata. It is interesting to note that the Spanish Royal Academy’s edition of Don Quixote, that celebrates its fourth centennial, claims to be based on about a hundred editions, old and new. If this is not remix, what is?

Cervantes himself is absolutely aware of what he is doing, and of the subversive

character of his action. When Don Quixote reads, we don’t know who is the madman, him or the one who wrote this:

The reason of the unreason with which my reason is afflicted so weakens my reason that with reason I murmur at your beauty.

Don Quixote changed forever the way novels were written, and three centuries later, Borges’ “Pierre Menard, author of Don Quixote” would change forever the way one reads. Pierre Menard writes Don Quixote without ceasing to be Pierre Menard, demonstrating how it is possible to transform a text without altering a single word. Decontextualization was inaugurated.

Following that tradition, X_Loaded presents us jodi’s map, images like, Olia Lialina’s, the conceptual text of Jennny Holzer, or Rosa Llop’s windmills.

With her windmills we have to say with Don Quixote, they are indeed giants.

X_Reloaded en español.

Santofile, usa el concepto de meme para aludir a libertad de creación en el mundo digital. Meme es mimesis y es autogenerador. Se refiere a mediación, en el sentido de remix, de mezclar apropiándose de trabajos de otros, generalmente trabajo digital que circula por la red, para a la vez producir una nueva obra original. Entre sus proyectos está X_Reloaded una interpretación del capítulo primero de El Quijote, que recoge obras dispares inspiradas por el cuarto centenario de su publicación.,

Se reunen creadores tan disímiles como William Burroughs y Adbusters, cuyo contexto comun sería precisamente la idea de romper, de volver trizas, que está en el seno mismo del verbo “to bust”. Al descontextualizar lo que se quiere romper, se le roba permanencia como ícono estático y se le confiere nueva vida dentro de un nuevo contexto.

Se reunen creadores tan disímiles como William Burroughs y Adbusters, cuyo contexto comun sería precisamente la idea de romper, de volver trizas, que está en el seno mismo del verbo “to bust”. Al descontextualizar lo que se quiere romper, se le roba permanencia como ícono estático y se le confiere nueva vida dentro de un nuevo contexto.

El escoger precisamente El Quijote como texto para X_Reloaded, es aludir al remix por excelencia. Cervantes se apropia de las novelas de caballería para subvertir el génro, y su remix final, al descontextualizarlas, es una obra unica y original. La impresión misma del texto en tiempos de Cervantes, requería de una copia altamente legible, lo que no necesariamente era el manuscrito original. De ahí que el “original” eran una copia hecha por uno o más amanuenses. Y de ese “original”corregido por el autor, salía el libro, armado por el cajista, con sus consiguientes errores. Es interesante notar que la edición de la Real Academia Española, con motivo del cuarto centenario de El Quijote, es un “texto crítico de la obra constituido sobre la consulta de cerca de un centenar de ediciones antiguas y modernas”. Si esto no es remix, ¿qué es?

Cervantes mismo es absolutamente consciente de lo que está haciendo, y del carácter subversivo de su acción. Cuando Don Qujiote lee no sabemos si es él el loco, o el que escribió esto:

La razón de la sinrazón que a mi razón se hace, de tal manera mi razón enflaquece, que con razón me quejo de la vuestra fermosura

El Quijote va a cambiar para siempre la manera como se escribe y tres siglos más tarde, “Pierre Menard autor del Quijote” de Borges, va a cambiar la manera como se lee. Pierre Menard escribe El Quijote sin dejar de ser Pierre Menard, demostrando cómo se transforma un texto sin cambiarlo, inaugurando la descontextualización.

Siguiendo esta tradición, X_Loaded nos presenta el mapa de jodi, imágenes como la de, Olia Lialina’, el texto conceptual de Jennny Holzer, o los molinos de viento de Rosa Llop’. Y con ellos, tenemos que decir con Don Quijote, los molinos son en verdad gigantes. Rosa Llop. Y con ellos, tenemos que decir con Don Quijote, los molinos son en verdad gigantes.

So, we wish to be able to hear poetry. Reading alone doesn’t do it any more. Sundiata belongs to an old, illustrious tradition, so do

So, we wish to be able to hear poetry. Reading alone doesn’t do it any more. Sundiata belongs to an old, illustrious tradition, so do

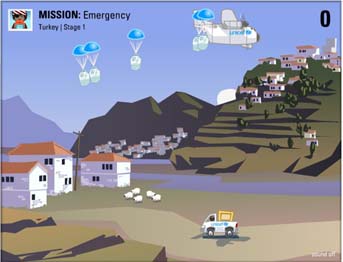

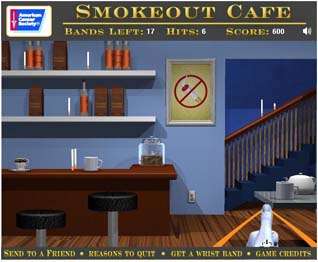

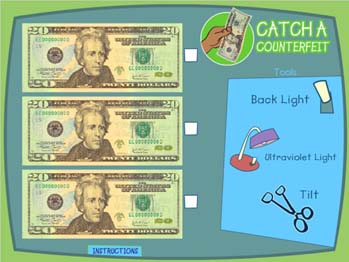

What they are doing is updating the old didactic tradition of using games to teach, they are teaching in the digital age. That brings me to my second thought, is the future of the book the domain of brainy sophisticates or is it a democratic move? In

What they are doing is updating the old didactic tradition of using games to teach, they are teaching in the digital age. That brings me to my second thought, is the future of the book the domain of brainy sophisticates or is it a democratic move? In