Talking of cinematic readings, I just came across LA artist Sandow Birk‘s visually stunning cinematic update of Dante’s Inferno. The film was made by laboriously creating a paper ‘toy theater’ and then shooting in live film, making for another complex contemporary interplay of paper with digital media.

Author Archives: sebastian mary

10 types of publication

In my other life, in the world of web startups, I often have to contend with people who are steadfastly convinced that everyone lives in the technical future. In this world, everyone blogs, knows what an RSS feed does, has an opinion on Yahoo! Pipes, and will be able to tell me why this list of characterizations of ‘the technical future’ is already obsolete. And yet Chris, in his introductory post as if:book’s co-director, remarks on ‘how so much reading promotion cuts literature off from other media, as if anyone still lives solely in a ‘world of books’.

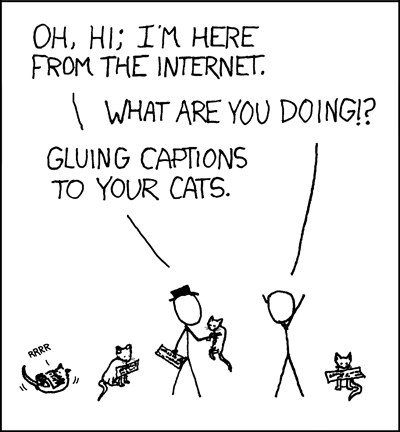

This strange inability of two worlds to acknowledge one another reminds me of a classic geek joke:

As Chris pointed out, we all exist in a world of multiple media outlets, which cross-fertilise vigoriously. But what have analog and digital to say about one another? At the first if:book:group meeting in London, Kate Pullinger remarked on how despite writing both print and digital fiction, her last print novel barely even mentioned the internet. Noga Applebaum pointed out how she’s devoted an entire PhD thesis to the overwhelmingly negative portrayals of technology in children’s fiction. Digital technology seems to appear in analog media only in cursory, fantastical or critical portrayals. Meanwhile, the ‘content’ of analog media is absorbed (digitized) into this brave new world, whose capacity for infinite reproducibility creates exciting new opportunities to see text in motion while causing a kerfuffle with its touted potential irreversibly to disrupt the established modus vivendi.

The relation between the worlds appears strangely asymmetrical. Print is at best a source of ‘content’, a sweet and outmoded ‘original’, sometimes a fetish. Even the lexicon reinforces this.

In a recent meeting, someone spotted me doodling, captured some doodle with his ‘analog to digital converter’ (ie a camera phone), and mailed it around. But what is it called if this image, thus digitized, is rendered in paper again? Is there a word for that? ‘Analogized’ doesn’t sound right (though I’m going to stick with it for the moment, faute de mieux).

The lack of a functioning concept of ‘analogization’ implies that we don’t need one, that there are 10 ways of publishing: those exploring, or eventually destined for digitization, and those destined for the scrap heap – or at best an obscure warehouse on the outskirts of asprawling megalopolis.

But is this true?

Geeks have a solid history of taking internet references back out into meatspace (pleasingly, the title of the above graphic, from the wonderful xkcd.com, is ‘in_ur_reality.png’). But it takes truly mass adoption of the internet to turn re-analogization of internet culture from being a nerdy in-joke to something you might see at Hallowe’en on the New York subway:

Rebecca Lossin, in a thoughtful comment on Chris’ recent post about Blake, remarks on “…something that while acknowledged by champions of electronic formats, is not dealt with very thoroughly. Books still seem more important than blogs. Big books seem even more important than little books.” Books, especially big books, are still associated with authority, thanks – she continues – to “…an extremely important aspect of reading: the acculturated reader.”

“The acculturated reader” sums succinctly what I was gesturing at when I posted about a messageboardful of average internet users debating the cultural significance of bookshelves. These readers, acculturated to the nexus of significations traditionally ascribed to physical books, navigate these significations in daily life but are additionally literate in internet discourse. Unlike many commentators on the apparent binary in play here, they see no competition or contradiction at all.

My introductory post on this blog was about how, as an aspiring (print) writer, I fell accidentally in love with the internet. As I explored the medium, my interest in print publication waned, and my suspicion grew that for a writer who wants her writing to change the world, there are more effective, instant-gratification – and digital – media out there that scratch the verbal itch without requiring the writer to receive 1,005,678 rejection letters and starve in obscurity for decades first (well, not the rejection letters anyway).

But since cocking that snook at the slow-moving world of print, I’ve spent the year pondering the relation between analog and digital writing. And I’ve concluded that there are more than 10 ways of publishing; that they are not in opposition to one another; and that a new generation of ‘acculturated readers’ is emerging that takes on board both the cultural significance of books and also the affordances of the internet, uses each tactically according to the kinds of writing/reading each facilitates best, and is beginning to explore the movement of content not just from analog to digital but also back to analog again.

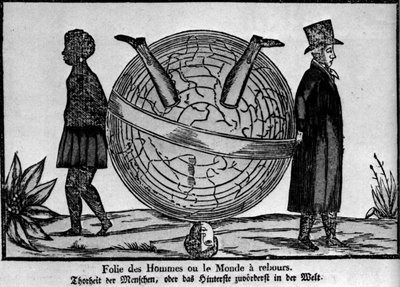

So here’s a beautiful example of a symbiosis of print and digital media, come full circle. BibliOdyssey is a gloriously eccentric blog dedicated to obscure, intriguing, unusual or visually stunning print art. Today I learned that the pick of BibliOdyssey is to be published as a physical book.

This trajectory – books that originate in blogs – pulls away from the narrative of ineluctable digitization that preoccupies much of the debate around the relation between print and the internet. Of course, it’s not new (remember Jessica Cutler?). But the BibliOdyssey book narrative is especially delicious (should that be del.icio.us?), as the material in the book consists of print images that were digitized, uploaded into scores of obscure online archives, collected by the mysterious PK on the BibliOdyssey blog and then re-analogized as a book. It’s an anthology of content that has come on a strange journey from print, through digitization and back to print again. So it’s possible to observe these images in multiple cultural contexts and investigate the response of ‘the acculturated reader’ in each. The question is: what does the material gain or lose in which medium?

The post-bit atom fascination of an ‘original’, a rare object, is powerful. But once digitized and uploaded into public-access archives (however byzantine, in practice, these are to navigate) this layer of interest is stripped, and value must be found elsewhere. Quirkiness; novelty; art-historical interest; the fleeting delight of stumbling upon something visually stunning whilst idly browsing. But the infinite reproducibility of the image means that it’s only of transactional value in a momentary, conversational sense: I send you that link to an amusing engraving, and our relationship is strengthened if you grasp why I sent that particular one and respond in kind.

The overall value of the blog, then, is in its function as dense repository of links that can be used thus. So what is the value of the images again once re-analogized? In the case of BibliOdyssey, it’s a beautiful coffee-table book, delightful in itself and that archly foregrounds its status as hip-to-the-internets.

Perhaps, a century down the line, when climate change has killed off the internet and we’re all living in candlelit huts, it’ll be a scarce and precious resource hinting at times gone by. But however the future pans out, right now it’s both evidence of the dialogic relation of analog and digital media, and also a palimpsest offering glimpses of the shifting signification of cultural content when published in different forms. Texts, images or collections of such aren’t just sitting there waiting to be digitized: once digitized, they take on new life, and increasingly creep back out into the analog world to glue captions to your cats.

ephemera

I had dinner last night with an elderly and eminent print collector and art historian. He specialises in the eighteenth century – the period when the quantity of text being produced last exploded by an order of magnitude – and embodies many of the assumptions of that period. The printed word is always meaningful; all printed matter is precious; even the minutiae of history are worth preserving.

So when not writing authoritative texts on engravings of Stubbs, he collects ephemera. To the uninitiated, that’s postcards, leaflets, adverts – basically anything printed, however trivial it might seem – and delivers great sacks of the stuff to the Bodleian Library at intervals to be sifted and, if deemed important, archived.

I tried to imagine what it would be like attempting to keep up with modern-day ephemera. I asked him: in an era of mass desktop self-publishing, is it even conceivable or possible to try and keep up? How can one collect and archive such stuff? He said they usually only take stuff from periods up to around the ’50s or ’60s as a rule. But somewhat to my surprise, he insisted that ephemera was more important today than ever, precisely because of computers: “Sooner or later anything on a computer gets erased. If we don’t collect some print how will anyone know what happened?”.

I’m not sure that delivering sacks of home-printed yoga adverts and party invitations to the Bodleian Library is the answer. But it did make me pause. While pamphlets, books and other ephemera give us some clue as to what life was like three centuries ago, what provisions are we making for our own mass memory? Will this neophiliac digital culture be stored on the future equivalent of floppy drives, only to end up becoming just as swiftly obsolete and unreadable? Answers on a postcard.

would you date someone with no books on their shelves?

I’m not completely sure about the netiquette of blogging about a conversation heard around the digital watercooler, ie on a close-knit community messageboard; but I came across one such recently that made me pause.

Paraphrased, the thread started out asking about the ethics of going through other people’s stuff. But it moved on to the subject of snooping on others’ bookshelves. The question then became: if you were left alone in someone else’s house the morning after a date, would you make a judgement about their suitability for future dates from their book collection? The answer was an overwhelming yes.

There were a few dissenting voices who muttered about intellectual snobbery, performance anxiety about their bookshelves, or even setting traps for book-snobs by displaying their Stephen King collection somewhere prominent. But the common element was a sense that someone’s book collection is an intimate portrait of their interests and/or aspirations, and can have a profound effect on others’ perceptions – to the point of being a romantic deal-breaker.

Books as extensions of personality is a familiar theme. But the context of the conversation, an internet messageboard, got me thinking. The theme of the messageboard in question is sexuality, and hence the community self-selects for reasons that have nothing to do with things intellectual/literary. I reckon it’s fair to say it was a small but reasonably random sample of moderately digitally-literate UK women.

Now, a familiar narrative in the publishing industry says that print is dying: see, for example, Jeff Gomez, Penguin USA’s director of online sales and marketing, on BBC Radio 4’s Open Book last week to promote his new (print!) book Print Is Dead. This narrative pits books against the internet, as though the latter either follows the former in some ineluctable evolution, or else the latter is a predatory force out to destroy culture as we know it. But this digital watercooler conversation, conducted amongst ‘normal’ internet-using people, suggests that these apocalyptic visions have more to do with industry angst than any widespread cultural shift among everyday users of print and digital media.

Despite a relatively high common standard of net literacy, no-one said ‘I wouldn’t care about lack of books – I’d be more worried about being stuck in a house with no wifi’. There was an overwhelming consensus that books are revealing, important and an insight into a stranger’s interests. The sense was not that digital media might replace books, but that they play different roles, and are perceived as different in kind – not just at the level of how they deliver ‘content’.

Such despatches from the middle ground might seem unglamorous in comparison with the giddy high-altitude futurism of Kelly et al, or pronouncements of the death of hard copy. But they’re worth noting. The cultural currency of books should not be conflated with the economics of producing them, such that a challenge to the latter is narrated as a collapse of the former. Though this might seem obvious, it’s one of the most common elisions in the discourse of print vs. online; it does little but muddy the debate, and has even less to do with lived reality for most people.

why are screens square?

More from the archive, I’m afraid; but I’ve quoted this so often in the last year that it merits repeating.

A video of Jo Walsh, a simultaneously near-invisible and near-legendary hacker I met through the University of Openess in London, talking about FOAF, Web3.0, geospatial data, the ‘One Ring To Rule Them All’ tendency of so-called ‘social media’ and the philosophies of making tech tools.

“Why are screens square?”, she asks. What follows is less a set of theories as a meditation on what happens when you start trying to think back through the layers of toolmaking that go into a piece of paper, a pen, a screen, a keyboard – the media we use to represent ourselves, and that we agree to pretend are transparent. This then becomes the starting-point for another meditation on who owns, or might own, our digital future.

(High-quality video so takes a little while to load)

cooking the books

I’ve been digging through old episodes of Black Books, a relatively little-known comedy series from the UK’s Channel 4. The show is set in a second-hand bookshop, run by Bernard Black, a chainsmoking, alcoholic Irishman (Dylan Moran) who shuts the shop at strange hours, swears at customers and becomes enraged when people actually want to buy his books.

It started me thinking about something Nick Currie said at the second Really Modern Library meeting. We were talking about mass digitization and the apparently growing appeal of ‘the original’, the ‘real thing’. The feel of a printed page; the smell of a first edition and so on. He mentioned a previous riff of his about ‘the post-bit atom’ – the one last piece of any analog cultural object that can’t be digitized – and which, in an age of mass digitisation, becomes fetishized to precisely the degree that the digitized object becomes a commodity.

So Black Books struck me as (besides being horribly funny) strangely poignant. While acerbic, in many ways it’s full of nostalgia for a kind of independent bookshop that’s rapidly disappearing. Bernard Black would be considerably less endearing if he was my only chance of getting the book I wanted; but that in the age of Amazon and Waterstone’s, he represents a post-bit atom of bibliophilia, and as such is ripe for fetishization.

anmoku no ryokai

A nice piece in this month’s Wired about “the manga industrial complex” in Japan, and the complex structure of tacitly-permitted copyright violation that powers the participatory fan culture around commercially-produced manga. Though the countless fan publications that take existing, copyrighted characters and repurpose them in new, surreal or pornographic environments are in explicit violation of copyright, the industry maintains an anmoku no ryokai (‘unspoken, implicit agreement’) to allow this culture to flourish – as it benefits everyone:

Taking care of customers. Finding new talent. Getting free market research. That’s a pretty potent trio of advantages for any business. Trouble is, to derive these advantages the manga industry must ignore the law. And this is where it gets weird. Unlike, say, an industrial company that might increase profits if it skirts environmental regulations imposed to safeguard the public interest, the manga industrial complex is ignoring a law designed to protect its own commercial interests.

This odd situation exposes the conflict between what Stanford law professor (and Wired contributor) Lawrence Lessig calls the “read only” culture and the “read/write” culture. Intellectual property laws were crafted for a read-only culture. They prohibit me from running an issue of Captain America through a Xerox DocuColor machine and selling copies on the street. The moral and business logic of this sort of restriction is unassailable. By merely photocopying someone else’s work, I’m not creating anything new. And my cheap reproductions would be unfairly harming the commercial interests of Marvel Comics.

But as Lessig and others have argued, and as the dojinshi markets amply confirm, that same copyright regime can be inadequate, and even detrimental, in a read/write culture. Amateur manga remixers aren’t merely replicating someone else’s work. They’re creating something original. And in doing so, they may well be helping, not hindering, the commercial interests of the copyright holders.

It’s interesting to speculate on whether J K Rowling’s publishers have the same attitude to the legions of fan writers busy generating Harry Potter slashfic; whether fanfic and slashfic is considered a meaningful contribution to the industries it riffs off, the way fan publications are recognised as such in the manga industry; and whether the idea of an anmoku no ryokai might be a useful addition to existing practice around copyright in a ‘read/write’ culture.

books and the man, part III: the new patronage

In the first ‘Books and the man’ post I took the example of Alexander Pope to argue that the idea of ‘high’ literature is inseparable from economic conditions that enable a writer to turn himself into a brand and sell copyrighted material to his readership. In this post I want to look at what happens to creative work in a medium whose very nature militates against copyright.

The internet encourages artists to give stuff away for free, and to capitalise (somehow) on abundance and reproducibility. Ben’s recent roundup of copyright-related readings quotes Jeff Jarvis to this effect: “It has taken 13 years of internet history for media companies to learn that, to give up the idea that they control something scarce they can charge consumers for.” So the answer, says Jay Rosen, is advertising: “Advertising tied to search means open gates for all users”. But while this works just fine for regularly-updated information-type content, how are works of imagination to be funded? As media professor Tim Jackson pointed out some years ago in Towards A New Media Aesthetic, the infinite reproducibility of content on the web threatens the livelihood of artists and writers to a degree that critics such as Keen believe will bring about the collapse of civilization as we know it.

Keen’s wrong. There were artists before there was copyright, and there will be afterwards. Leaving aside my speculations about experiments such as Meta-Markets, cultural forms are starting to emerge online that make use of the internet’s mutability, endlessness, unreliability and infinitely-reproducible nature. But they’re not ‘high art’, in the sense that Pope pioneered. Rather, they hark back to an earlier period of literature when aristocratic patronage was the norm, and there was little distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art except in the sense of being calibrated to the tastes of the target audience.

I’ve written here previously about the ways in which alternate reality gaming is the first genuinely net-native storytelling form. I complained that this exciting form was emerging and was already being colonised by the advertising industry, through sponsorship and similar. Where and how, I wondered, would the ‘independent’ ARGs emerge?

I’d like to eat my words. Calling for ‘independent’ ARGs invoked the perspective of those cultural assumptions of ‘independence’ that both created and were created by the scarcity business model of copyright. In doing so, I ignored the fact that the internet doesn’t use a scarcity model – and hence that the concept of ‘independence’ doesn’t work in the same way. And internet users don’t seem to care that much about it.

I asked Perplex City creator Dan Hon whether he thought there was a bias, or any qualitative difference, between ‘independent’ and sponsored ARGs. He told me that ARG enthusiasts don’t reall care: “It’s normally the execution of the game that will have the most impact.”

So for enthusiasts of the internet’s first native storytelling form, the issue of whether corporate sponsorship is acceptable (an idea which would beanathema to anyone raised in the modernist tradition of authorship) is completely meaningless. If anything, Dan reckons ‘independence’ counts against you: “There absolutely isn’t any value-laden bias towards indie-ARGs – in fact, if anything there’s a negative bias against them. Many players […] are quite happy to give warnings that the indie args are liable to spontaneously implode just because the people behind them are “too indie”. A quick nose around the ‘ARGs with Potential’ section on the Unfiction boards turns up enough ‘This looks like a dodgy indie affair’ style remarks to back up this statement.

So while the arts world “was divided between shock and hilarity” when Fay Weldon got jewellers Bulgari to pay an undisclosed amount for frequent mentions in a 2001 novel, there are no anxieties in the ARG community about seeing advertising converge with the arts. Perhaps one could argue that ARGers are typically computer gaming enthusiasts too, and if they can cope with expensive Playstation games they can cope with Playstation-sponsored stories.

But. Take a look at Where Are The Joneses?, a collaboratively-written, professionally-filmed and Creative Commons-licenced online sitcom devised by former Channel 4 new media schemer David Bausola. Not an ARG; but a near-perfect instance of bottom-up culture. Written by its community, quality-checked by the production team, funny, absorbing, released on open licence – and an advert for Ford Motors.

If you catch him in an expansive mood, David will tell you that the marketing industry will survive only if it stops trying to influence culture and just starts making it. The flip side of that is that vested interests will, increasingly, explicitly find their way into creative works produced online. And, in my view, that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

A glance at some of the scions of the pre-eighteenth-century canon gives a hint at the role that aristocratic patronage played in the arts. To hear some of the anti-internet rearguard speak, one might think that To Penshurst was written independently of the relation between Sir Robert Sidney and Ben Jonson; one might think that the arts has always been unsullied by power; that the encroachment of the the latter (in the form of commerce) on the former is a sign of our imminent cultural disintegration.

But contrary to Keen’s assertion that the mechanisms of copyright are indispensable to cultural dynamism, the English cultural renaissance that gave us Shakespeare, Bacon, Sidney, Donne, Marvell et al was largely driven by aristocratic patronage. Copyright hadn’t been invented yet. And if the world of art and culture is to survive in a post-copyright environment, it may be time to look furthe back in the past than the eighteenth century, and re-examine previous models. Which means looking again at patronage, which in turn, today, makes a strong case for embracing the advert. With the distinctions between brand patronage and creative culture already collapsing, it may be time for artists to wake up to the power they could wield by embracing and negotiating with the vested interests of corporate sponsors. If they do, the result may yet be a digital Renaissance.

books and the man, part II (sort of)

So in my last post I compared the sentiments expressed in Pope’s Dunciad to those of Andrew Keen’s The Cult of The Amateur, and suggested some parallels between the eighteenth-century print boom and the explosion of user-generated content in web2.0. The point I wanted to make was that the model of content production championed by Keen is historically-specific and relies on an economic context where printed matter is common enough to be marketed to the general public, but still scarce enough to enable writers to make a living from selling units of content to their audiences.

I’ve been gnawing for some time at the question of what happens to creative writers – or artists in general – in a world where success of content is based not on its scarcity (the ‘high art’ model) but on ubiquity and infinite reproducibility. If copyright no longer exists, how can (already often cash-strapped) independent arts workers sell their work? And what will they do if they can’t?

So I was intrigued to come across Meta-Markets, an experiment by MIT media artist Burak Arikan, currently in beta. In this ‘marketplace’, users can ‘IPO’ shares in del.icio.us links, Feedburner feeds, Flickr profile views and the like. It’s pleasing in a surreal way to watch shares in ‘you’ going up and down – particularly as I’m trading from London and most of the others are based in NY, so the stocks go crazy at weird times of the day and night relative to me. But it also provokes some intriguing speculations around the potential to create an economic model for the arts online that is genuinely based on the internet’s drive toward reproducibility rather than scarcity.

One of Arikan’s stated aims with Meta-Markets is to explore ways in which creative types can leverage their immaterial labor as new kinds of ‘currency’ – in other words, to find a business model for trading cultural stuff online that isn’t dependent on price per copyrighted unit. And it starts some intriguing trains of thought. In order to ‘IPO’ a link, you have to have been the first to bookmark it, and at least 10 others have to have bookmarked it after you. So it requires both some minimal popularity, and also a ‘first claim’ ownership. I was irked to find, for example, that I couldn’t bookmark my own website and then sell stocks in it, because someone else already ‘owns’ that link.

So, I wondered, what if real money were involved? Supposing my website suddenly shot up the Alexa rankings, would I be in a position of watching someone else make a fortune on ‘ownership’ of my bookmarks? Or would the first thing to do after launching something online be to bookmark the URL so as to ensure you can trade on its popularity? Following that train of thought a little further, it’s possible to imagine some folksonomic inversion of the centralised copyright law taking the place of the existing system. This might then enable artists and writers to claim a fuzzy, emergent ‘ownership’ of creative online work and thus to find ways of making a living from it.

But I think that’s a long way off, if it ever happens at all. Meanwhile, we’re a long way from having any consistently viable independent revenue model for online artists, who find themselves between starvation, corporate sponsorship and the sometimes rather stodgy world of public/philanthropic arts funding. But again, maybe that’s not such a bad thing, of which more next time…

content syndicate

While Andrew Keen laments the decline of professionalised content production, and Publishing2.0 fuels the debate about whether there’s a distinction between ‘citizen journalism’ and the old-fashioned sort, I’ve spent the morning at Seedcamp talking with a Dubai-based entrepreur who’s blurring the distinction even further.

Content Syndicate is a distributed marketplace for buying, selling and commissioning content (By that they mean writing). Submitted content is quality-assessed first automatically and then by human editors, and can be translated by the company staff if required. They’ve grown since starting a year or so ago to 30 staff and a decent turnover.

This enterprise interests me because it picks up on some recurring themes around the the changes digitisation brings to what a writer is, and what he or she does. In some respects, this system commodifies content to an extent traditionalists will find horrifying – what writer, starting out (as many do) wanting to change the world, will feel happy having their work fed through a semiautomatic system in which they are a ‘content producer’? But while it may be helping to dismantle – in practice – the distinction between professional and amateur writers, and thus risking helping us towards Keen’s much-lamented mulch of unprofessionalised blah, but at least people are getting paid for their efforts. And you can rebut this last fear of unprofessionalised blah by saying that at least there’s some quality control going on. (The nature of the quality control is interesting too, as it’s a hybrid of automated assessment and human idiot-checking; this bears some thinking about as we consider the future of the book.)

So this enterprise points towards some ways in which we’re learning to manage, filter and also monetise this world of increasingly-pervasive ‘content everywhere’, and suggests some of the realities in which writers increasingly work. I’ll be interested to see how we adapt to this: will the erstwhile privileged position of ‘writers’ give way as these become mere grunts producing ‘content’ for the maw of the market? Or will some subtler and more nuanced bottom-up hierarchy of writing excellence emerge?