In his recent article “Why We Need a Corporation for Public Gaming,” David Rejeski proposes the creation of a government funded entity for gaming to be modeled after the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). He compares the early days of television to the early days of video gaming. 20 years after the birth of commercial broadcast television, he notes that the Lyndon Johnson administration created CPB to combat to the “vast wasteland of television.” CPB started with an initial $15 million budget (which has since grown to $300 million). Rejeski propose a similar initial budget for a Corporation for Public Gaming (CPG). For Rejeski, video games are no longer sequestered to the bedroom of teenage boys, and are as an important medium in our culture as is television. He notes “that the average gamer is 30 years old, that over 40 percent are female, and that most adult gamers have been playing games for 12 years.” He also cites examples of how a small but growing movement of “serious games” are being used towards education and humanitarian ends. By claiming that a diversity of video games is important for the public good, and therefore important for the government to fund, he implies that these serious games are good for democracy.

In his recent article “Why We Need a Corporation for Public Gaming,” David Rejeski proposes the creation of a government funded entity for gaming to be modeled after the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). He compares the early days of television to the early days of video gaming. 20 years after the birth of commercial broadcast television, he notes that the Lyndon Johnson administration created CPB to combat to the “vast wasteland of television.” CPB started with an initial $15 million budget (which has since grown to $300 million). Rejeski propose a similar initial budget for a Corporation for Public Gaming (CPG). For Rejeski, video games are no longer sequestered to the bedroom of teenage boys, and are as an important medium in our culture as is television. He notes “that the average gamer is 30 years old, that over 40 percent are female, and that most adult gamers have been playing games for 12 years.” He also cites examples of how a small but growing movement of “serious games” are being used towards education and humanitarian ends. By claiming that a diversity of video games is important for the public good, and therefore important for the government to fund, he implies that these serious games are good for democracy.

Rejeski raises an important idea (which I agree with), that gaming has more potential activities than saving princesses or shooting everything in sight. Fortunately, he acknowledges that government funded game development will not cure all the ill effects he describes. In that, CPB funded television programs did not fix television programming and has its own biases. Rejeski admits that ultimately “serious games, like serious TV, are likely to remain a sidebar in the history of mass media.” My main contention with Rejeski’s call is his focus on the final product or content, in this case, comparing a video game with a television program. His analogy fails to recognize the equally important components of the medium, production and distribution. If we look at video games in terms of production, distribution as well as content, the allocation of government resources envision a different outcome. In this analysis, a more efficient use of funds would be geared towards creating tools to create games, insuring fair and open access to the network, and less emphasis funded towards the creation of actual games.

1. Production:

Perhaps, rather than television, a better analogy would be to look at the creation of the Internet, which supports many to many communication and production. What started as a military project under DARPA, Internet protocols and networks became a tool which people used for academic, commercial, and individual purposes. A similar argument could be made for the creation of a freely distributed game development environment. Although the costs associated with computation and communication are decreasing, high-end game development budgets for titles such as the Sims Online and Halo 2 are estimated to run in the tens of millions of dollars. The level of support are required to create sophisticated 3D and AI game engines.

Educators have been modding games of this caliber. For example, the Education Arcade’s game, Revolution, teaches American History. The game was created using the Neverwinter Nights game engine. However, problems often arise because the actions of characters are often geared towards the violent, and male and female models are not representative of real people. Therefore, rather than focusing on the funding of games, creating a game engine and other game production tools to be made open source and freely distributed would provide an important resource for the non-commerical gaming community.

There are funders who support the creation of non-commerical games, however as with most non-commerical ventures, resources are scare. Thus, a game development environment, released under a GPL-type licensing agreement, would allow serious game developers to use their resources for design and game play, and potentially address issues that may be too controversial for the government to fund. Issues of government funding over controversial content, be it television or games, will be addressed further in this analysis.

2.Distribution:

In Rejecki’s analogy of television, he focuses on the content of the one to many broadcast model. One result of this focus is the lack of discussion on the equally important use of CPB funds to support the Public Broadcast Services (PBS) that air CPB funded programs. By supporting PBS, an additional voice was added to the three television networks which in theory is good for a functioning democracy. The one to many model also discounts the power of the many to many model that is enabled by a fairly accessible network.

In the analogy of television and games, air waves and cables are tightly controlled through spectrum allocation and private ownership of cable wires. Individual production of television programming is limited to public access cable. The costs of producing and distributing on-air television content is extremely expensive, and does not decreasingly scale. That is, a two minute on-air television clip is still expensive to produce and air. Where as, small scale games can be created and distributed with limited resources. In the many to many production model, supporting issues as network neutrality or municipal broadband (along with new tools) would allow serious games to increase in sophistication, especially as games increasingly rely on the network for not only distribution, but game play as well. Corporation for Public Gaming does not need to pay for municipal broadband networks. However, legislative backers of a CPG need to recognize that an open network are equally linked to non-commerical content, as the CPB and PBS are. Again, keeping the network open will allow more resources to go toward content.

3. Content:

The problem with government funded content, whether it be television programs or video games, is that the content will always been under the influence of the mainstream cultural shifts. It may be hard to challenge the purpose of creating games to teach people about children diabetics glucose level management or balancing state budgets. However, games to teach people about HIV/AIDS education, evolution or religion are harder for the government to fund. Or better yet, take Rejeski’s example of the United Nation World Food Program game on resource allocation for disaster relief. What happens with this simulation gets expanded to include issues like religious conflicts, population control, and international favoritism?

Further, looking at the CPB example, it is important to acknowledge the commercial interests in CPB funded programs. Programs broadcast on PBS receive funding from CPB, private foundations, and corporate sponsorship, often from all three for one program. It becomes increasingly hard to defend children’s television as “non-commerical,” when one considers the proliferation of products based on CPB funded children’s educational shows, such as Sesame Street’s “Tickle me Emo” dolls. Therefore, we need to be careful, when we discuss the CPB and PBS programs as “non-commercial.”

Therefore, commercial interests are involved in the production of “public television,” and will be effected by commerical interests, even if it is to a lesser degree than commercial network programming. Investment in fair distribution and access to the network , as well as the development of accessible tools for gaming production would allow more opportunity for the democratization of game development that Rejeski is suggesting.

Currently, many of the serious games being created are niche games, with a very specific, at times, small audience. Digital technologies excel in this many to many model. As opposed to the one to many communication model of television, the many to many production of DYI game design allows for many more voices. Some segment of federal grants to support these games will fall prey to criticism, if the content strays too far from the current mainstream. The vital question than, is how do we support the diversity of voices to maintain a democracy in the gaming world given the scare resource of federal funding. Allocating resources towards tools and access may then be more effective overall in supporting the creation of serious games. Although I agree with Rejeski’s intentions, I suggest the idea of government funded video games needs to expand to include production and distribution, along with limited support of content for serious games.

Author Archives: ray cha

another round: britannica versus wikipedia

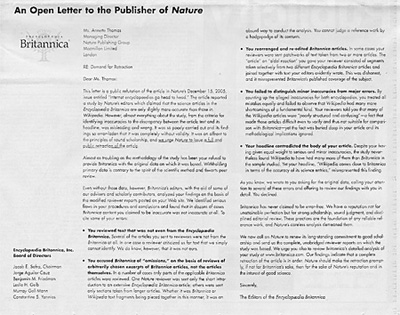

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

Several interesting things are going on here. Because Britannica chose to place an ad in the Times, it shifted the argument and debate away from the peer review / editorial context into one of rhetoric and public relations. Further, their conscious move to take the argument to the “public” or the “masses” with an open letter is ironic because the New York TImes does not display its print ads online, therefore access of the letter is limited to the Time’s print readership. (Not to mention, the letter is addressed to the Nature Publishing Group located in London. If anyone knows that a similar letter was printed in the UK, please let us know.) Readers here can click on the thumbnail image to read the entire text of the letter. Ben raised an interesting question here today, asking where one might post a similar open letter on the Internet.

Britannica cites many important criticisms of Nature’s article, including: using text not from Britannica, using excerpts out of context, giving equal weight to minor and major errors, and writing a misleading headline. If their accusations are true, then Nature should redo the study. However, to harp upon Nature’s methods is to miss the point. Britannica cannot do anything to stop Wikipedia, except to try to discredit to this study. Disproving Nature’s methodology will have a limited effect on the growth of Wikipedia. People do not mind that Wikipedia is not perfect. The JKF assassination / Seigenthaler episode showed that. Britannica’s efforts will only lead to more studies, which will inevitably will show errors in both encyclopedias. They acknowledge in today’s letter that, “Britannica has never claimed to be error-free.” Therefore, they are undermining their own authority, as people who never thought about the accuracy of Britannica are doing just that now. Perhaps, people will not mind that Britannica contains errors as well. In their determination to show the world that of the two encyclopedias which both content flaws, they are also advertising that of the two, the free one has some-what more errors.

In the end, I agree with Ben’s previous post that the Nature article in question has a marginal relevance to the bigger picture. The main point is that Wikipedia works amazingly well and contains articles that Britannica never will. It is a revolutionary way to collaboratively share knowledge. That we should give consideration to the source of our information we encounter, be it the Encyclopedia Britannica, Wikipedia, Nature or the New York Time, is nothing new.

next text: new media in history teaching and scholarship

The next text project came forth from the realization that twenty-five years into the application of new media to teaching and learning, textbooks have not fully tapped the potential of new media technology. As part of this project, we have invited leading scholars and practitioners of educational technology from specific disciplines to attend meetings with their peers and the institute. Yesterday, we were fortunate to spend the day talking to a group of American History teachers and scholars, some of whom created seminal works in history and new media. Over the course of the day, we discussed their teaching, their scholarship, the creation and use of textbooks, new media, and how to encourage the birth of the next generation born digital textbook. By of the end of the day, the next text project started to take a concrete form. We began to envision the concept of accessing the vast array of digitized primary documents of American History that would allow teachers to formulate their own curricula or use guides that were created and vetted by established historians.

Attendees included:

David Jaffe, City University of New York

Gary Kornblith, Oberlin College

John McClymer, Assumption College

Chad Noyes, Pierrepont School

Jan Reiff, University of California, Los Angeles

Carl Smith, Northwestern University

Jim Sparrow, University of Chicago

Roy Rosenzweig, George Mason University

Kate Wittenberg, EPIC, Columbia University

The group contributed to influential works in the field of History and New Media, including Who Built America, The Great Chicago Fire and The Web of Memory, The Encyclopedia of Chicago, the Blackout History Project, the Visual Knowledge Project, History Matters,the Journal of American History Textbook and Teaching Section, and the American History Association Guide to Teaching and Learning with New Media.

Almost immediately, we found that their excellence in their historical scholarship was equally matched in their teaching. Often their introductions to new media came from their own research. Online and digital copies of historical documents radically changed the way they performed their scholarship. It then fueled the realization that these same tools afforded the opportunity for students to interact with primary documents in a new way which was closer to how historians work. Often, our conversations gravitated back to teaching and students, rather than purely technical concerns. Their teaching led them to the forefront of developing and promoting active learning and constructionist pedagogies, by encouraging an environment of inquiry-based learning, rather than rote memorization of facts, through the use of technology. In these new models, students are guided to multiple paths of self-discovery in their learning and understanding of history.

We spoke at length on the phrase coined by attendee John McClymer, “the pedagogy of abundance.” With access to rich archives of primary documents of American history as well as narratives, they are not faced with the problems of

The discussion also included issues of resistance, which were particularly interesting to us. Many meeting participants mentioned student resistance to new methods of learning including both new forms of presentation and inquiry-based pedagogies. In that, traditional textbooks are portable and offer an established way to learn. They noted an institutional tradition of the teacher as the authoritative interpreter in lecture-based teaching, which is challenged by active learning strategies. Further, we discussed the status (or lack of) of the group’s new media endeavors in both their scholarship and teaching. Depending upon their institution, using new media in their scholarship had varying degrees of importance in their tenure and compensation reviews from none to substantial. Quality of teaching had no influence in these reviews. Therefore, these projects were often done, not in lieu of, but in addition to their traditional publishing and academic professional requirements.

The combination of an abundance of primary documents (particulary true for American history) and a range of teaching goals and skills led to the idea of adding layers on top of existing digital archives. Varying layers could be placed on top of these resources to provide structure for both teachers and students. Teachers who wanted to maintain the traditional march through the course would still be able to do so through guides created by the more creative teacher. Further, all teachers would be able to control the vast breadth of material to avoid overwhelming students and provide scaffolding for their learning experience. We are very excited by this notion, and will further refine the meeting’s groundwork to strategize how this new learning environment might get created.

We are still working through everything that was discussed, however, we left the meeting with a much clearer idea of the landscape of the higher education history teacher / scholar, as well as, possible directions that the born digital history textbook could take.

copyright debates continues, now as a comic book

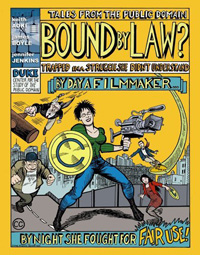

Keith Aoki, James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins have produced a comic book entitled, “Bound By Law? Trapped in a Sturggle She Didn’t Understand” which portrays a fictional documentary filmmaker who learns about intellectual property, copyright and more importantly her rights to use material under fair use. We picked up a copy during the recent conference on “Cultural Environmentalism at 10” at Stanford. This work was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the same people who funded “Will Fair Use Survive?” from the Free Expression Policy Project of the Brennan Center at the NYU Law School, which was discussed here upon its release. The comic book also relies on the analysis that Larry Lessig covered in “Free Culture.” However, these two works go into much more detail and have quite different goals and audiences. With that said, “Bound By Law” deftly takes advantage of the medium and boldly uses repurposed media iconic imagery to convey what is permissible and to explain the current chilling effect that artists face even when they have a strong claim of fair use.

Keith Aoki, James Boyle and Jennifer Jenkins have produced a comic book entitled, “Bound By Law? Trapped in a Sturggle She Didn’t Understand” which portrays a fictional documentary filmmaker who learns about intellectual property, copyright and more importantly her rights to use material under fair use. We picked up a copy during the recent conference on “Cultural Environmentalism at 10” at Stanford. This work was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the same people who funded “Will Fair Use Survive?” from the Free Expression Policy Project of the Brennan Center at the NYU Law School, which was discussed here upon its release. The comic book also relies on the analysis that Larry Lessig covered in “Free Culture.” However, these two works go into much more detail and have quite different goals and audiences. With that said, “Bound By Law” deftly takes advantage of the medium and boldly uses repurposed media iconic imagery to convey what is permissible and to explain the current chilling effect that artists face even when they have a strong claim of fair use.

Part of Boyle’s original call ten years ago for a Cultural Environmentalism Movement was to shift the discourse of IP into the general national dialogue, rather than remain in the more narrow domain of legal scholars. To that end, the logic behind capitalizing on a popular culture form is strategically wise. In producing a comic book, the authors intend to increase awareness among the general public as well as inform filmmakers of their rights and the current landscape of copyright. Using the case study of documentary film, they cite many now classic copyright examples (for example the attempt to use footage of a television in the background playing the”Simpsons” in a documentary about opera stagehands.) “Bound By Law” also leverages the form to take advantage of compelling and repurposed imagery (from Mickey Mouse to Mohammed Ali) to convey what is permissible and the current chilling effect that artists face in attempting to deal with copyright issues. It is unclear if and how this work will be received in the general public. However, I can easily see this book being assigned to students of filmmaking. Although, the discussion does not forge new ground, its form will hopefully reach a broader audience. The comic book form may still be somewhat fringe for the mainstream populus and I hope for more experiments in even more accesible forms. Perhaps the next foray into the popular culture will an episode of CSI or Law & Order, or a Michael Crichton thriller.

if:book-back mountain: emergent deconstruction

It’s Oscar weekend, and everyone seems to be thinking and talking about movies, including myself. At the institute we often talk about the discourse afforded by changes in technology, and it seems to be apropos to take a look at new forms of discourse in area of movies. A month or so ago, I was sent the viral Internet link of the week. Someone made a parody of the Brokeback Mountain trailer by taking its soundtrack and tag lines and remixng them with scenes from the flight school action movie, Top Gun. Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer are recast as gay lovers, misunderstood in the world of air to air combat. The technique of remixing a new trailer first appeared in 2005, with clips from the Shining recut as a romantic comedy to hilarious effect. With spot-on voiceover and Peter Gabriel’s “Solsbury Hill” as music, it similarly circulated the Internet, while consuming office bandwidth. The first Brokeback parody is uncertain, however, it inspired the p2p/ mashup (although some purists question whether these trailers are true mashup) community to create dozens of trailers. Virginia Heffernan in the New York Times gives a very good overview of the phenomenon, including the depictions of Fight Club, Heat, Lord of the Rings, and Stars War as a gay love story.

Some spoofs work better than others. The more successful trailers establish the parallels between the loner hero archetype of film and the outsider qualities of gay life. For example, as noted by Heffernana, Brokeback Heat, with limited extra editing, transforms Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro from a detective and criminal into lovers, who wax philosophically on the intrinsic nature of their lives and their lack of desire to live another way. Or in Top Gun 2: Brokeback Squadron, Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer exist in their own hyper-masculine reality outside of the understanding of others, in particular their female romantic counterparts. In Back to the Future, the relationship of mentor and hero is reinterpreted as a cross generational romance. Lord of the Rings: Brokeback Mount Doom successfully captures the analogy between the perilous journey of the hero and the experience of the disenfranchised. Here, the quest of Sam and Frodo is inverted into the quest to find the love that dares not speak its name. The p2p/ mashup community had come to the same conclusion (to, at times, great comic effect) that the gay community arrived at long ago, that male bonding (and its Hollywood representation) has a homoerotic subtext.

The loner heros found in the the Brokeback Mountain remixes are of particular interest. Over time, the successful parodies deconstruct the Hollywood imagery of the hero, and subsequently distill the archetypes of cinema. This process of distillation identifies key elements of the male hero. The common traits of the hero being that he lies outside the mainstream, cannot fight his rebel “nature”, often uses the guidance of a mentor and must travel a perilous journey of self discovery all rise to the surface of these new media texts. The irony plays out, when their hyper-masculinity are juxtaposed next to identical references of the supposed taboo gay experience.

On the other hand, the Arrested Development version contains titles thanking the cast and producers of the cancelled series, clips of Jason Bateman’s television family suggesting his latent homosexuality, and the Brokeback Mountain theme music. The disparate pieces make less sense, rendering it ultimately less interesting as a whole. Likewise, Brokeback Ranger, a riff on Chuck Norris in the Walker, Texas Ranger television series, is a collection of clips of the Norris fighting and solving crimes, with the prerequisite music, and titles that describe Norris ironic superhuman abilities including dividing by zero. Again, the references are not of the hero archetype and the piece, although mildly humorous, has limited depth.

A potentially new form of discourse is being created, in which the archetypes of media text emerge from their repeated deconstruction and subsequent reconstruction. From these works, an understanding of the media text appears through an emergent deconstruction. In that, the individual efforts need not be conscious or even intended. Rather, the funniest and most compelling examples are the remixes which correctly identify and utilize the traditional conventions in the media text. Therefore, their success is directly correlated to their ability to correctly identify the archetype.

The users may not have prior knowledge of the ideas of the hero described by Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Nor are they required to have read Umberto Eco’s deconstruction of James Bond, or Leslie Fiedler’s work on the homosexual subtext found in the novel. Further, each individual remix author does not need to set out to define the specific archetypes. What is most extraordinary is that their aggregate efforts gravitate towards the distilled archetype, in this case, the male bonding rituals of the hero in cinema. Some examples will miss the themes, which is inherent in all emergent systems. By the definition and nature of archetypes, the work that most resonate are the ones which most convincingly identify, reference, (and in this case, parody) the archetype. These analyses can be discovered by an individual, as Campbell, Eco, Jung and Fiedler did. Since their groundbreaking works, there is an abundance of deconstructing media text from the last fifty years. Here, the lack of intention, and the emergence of the archetypes through the aggregate is new. An important aspect of these aggregate analyses is that they could only come about through the wide availability of both access to the network and to digital video editing software.

At the institute, we expect that the dissemination of authoring tools and access to the network will lead to new forms of discourse and we look for occurrences of them. Emergent deconstruction is still in its early stages. I am excited by its prospects, but how far it can meaningfully grow is unclear. However, I do know that after watching thirty some versions of the Brokeback Mountain remixed trailers, I do not need to hear its moody theme music any more, but I suppose that is part of the process of emergent forms.

the email tax: an internet myth soon to become true

After years as an Internet urban myth, the email tax appears to be close at hand. The New York TImes reports that AOL and Yahoo have partnered with startup Goodmail to start offering guaranteed delivery of mass email to organizations for a fee. Organizations with large email lists can pay to have their email go directly to AOL and Yahoo customers’ inboxes, bypassing spam filters. Goodmail claims that they will offer discounts to non-profits.

Moveon.org and the Electronic Frontier Foundation have joined together to create an alliance of nonprofit and public interest organizations to protest AOL’s plans. They argue that this two-tiered system will create an economic incentive to decrease investment into AOL’s spam filtering in order to encourage mass emailers to use the pay-to-deliver service. They have created an online petition called dearaol.com for people to request that AOL stop these plans. A similar protest to Yahoo who intends to launch this service after AOL is being planned as well. The alliance has created unusual bedfellows, including Gun Owners of America, AFL-CIO, Humane Society of United States and Human Rights Campaign, who are resisting the pressure to use this service.

Part of the leveling power of email is that the marginal cost of another email is effectively zero. By perverting this feature of email, smaller businesses, non-profits, and individuals will once again be put at a disadvantage to large affluent firms. Further, this service will do nothing to reduce spam, rather it is designed to help mass emailers. An AOL spokesman, Nicholas Graham is quoted as saying AOL will earn revenue akin to a “lemonade stand” which further questions by AOL would pursue this plan in the first place. Although the only affected parties will initially be AOL and Yahoo users, it sets a very dangerous precedent that goes against the democratizing spirit of the Internet and digital information.

blu-ray, amazon, and our mediated technology dependent lives

A couple of recent technology news items got me thinking about media and proprietary hardware. One was the New York Times report of Sony’s problems with its HD-DVD technology, Blu-Ray, which is causing them to delay the release of their next gaming system, the PS3. The other item was Amazon’s intention of entering the music subscription business in the Wall Street Journal.

The New York Times gives a good overview on the up coming battle of hardware formats for the next generation of high definition DVD players. It is the Betamax VHS war from the 80s all over again. This time around Sony’s more expensive / more capacity standard is pitted against Toshiba’s cheaper but limited HD-DVD standard. It is hard to predict an obvious winner, as Blu-Ray’s front runner position has been weaken by the release delays (implying some technical challenges) and the recent backing of Toshiba’s standard by Microsoft (and with them, ally Intel follows.) Last time around, Sony also bet on the similarly better but more expensive Betamax technology and lost as consumers preferred the cheaper, lesser quality of VHS. Sony is investing a lot in their Blu-Ray technology, as the PS3 will be founded upon Blu-Ray. The standards battle in the move from VHS to DVD was avoided because Sony and Philips decided to scrap their individual plans of releasing a DVD standard and they agreed to share in the revenue of licensing of the Toshiba / Warner Brothers standard. However, Sony feels that creating format standards is an area of consumer electronics where they can and should dominate. Competing standards is nothing new, and date back to at least to the decision of AC versus DC electrical current. (Edison’s preferred DC lost out to Westinghouses’ AC.) Although, it does provide confusion for consumers who must decide which technology to invest in, with the potential danger that it may become obsolete in a few years.

On another front, Amazon also recently announced their plans to release their own music player. In this sphere, Amazon is looking to compete with iTunes and Apple’s dominance in the music downloading sector. Initially, Apple surprised everyone with the foray into the music player and download market. What was even more surprising was they were able to pull it off, shown by their recent celebration of the 1 billionth downloaded song. Apple continues to command the largest market share, while warding off attempts from the likes of Walmart (the largest brick and mortar music retailer in the US.) Amazon is pursuing a subscription based model, sensing that Napster has failed to gain much traction. Because Amazon customers already pay for music, they will avoid Napster’s difficult challenge of convincing their millions of previous users to start paying for a service that they once had for free, albeit illegally. Amazon’s challenge will be to persuade people to rent their music from Amazon, rather than buy it outright. Both Real and Napster only have a fraction of Apple’s customers, however the subscription model does have higher profit margins than the pay per song of iTunes.

It is a logical step for Amazon, who sells large numbers of CDs, DVDs and portable music devices (including iPods.) As more people download music, Amazon realizes that it needs to protect its markets. In Amazon’s scheme, users can download as much music as they want, however, if they cancel their subscription, the music will no longer play on their devices. The model tests to see if people are willing to rent their music, just like they rent DVDs from Netflix or borrow books from the library. I would feel troubled if I didn’t outright own my music, however, I can see the benefits of subscribing to access music and then buying the songs that I liked. However, it appears that if you will not be able to store and play your own MP3s on the Amazon player and the iPod will certainly not be able to use Amazon’s service. Amazon and partner Samsung must create a device compelling enough for consumers drop their iPods. Because the iPod will not be compatible with Amazon’s service, Amazon may be forced to sell the players at heavy discounts or give them to subscribers for free, in a similar fashion to the cell phone business model. The subscription music download services have yet to create a player with any kind of social or technical cachet comparable to the cultural phenomenon of the iPod. Thus, the design bar has been set quite high for Amazon and Samsung. Amazon’s intentions highlight the issue of proprietary content and playback devices.

While all these companies jockey for position in the marketplace, there is little discussion on the relationship between wedding content to a particular player or reader. Print, painting, and photography do not rely on a separate device, in that the content and the displayer of the content, in other words the vessel, are the same thing. In the last century, the vessel and the content of media started to become discreet entities. With the development of transmitted media of recorded sound, film and television, content required a player and different manufacturers could produce vessels to play the content. Further, these new vessels inevitably require electricity. However, standards were formed so that a television could play any channel and the FM radio could play any FM station. Because technology is developing at a much faster rate, the battle for standards occur more frequently. Vinyl records reigned for decades where as CDs dominated for about ten years before MP3s came along. Today, a handful of new music compression formats are vying to replace MP3. Furthermore, companies from Microsoft and Adobe to Sony and Apple appear more willing to create proprietary formats which require their software or hardware to access content.

As more information and media (and in a sense, ourselves) migrate to digital forms, our reliance on often proprietary software and hardware for viewing and storage grows steadily. This fundamental shift on the ownership and control of content radically changes our relationship to media and these change receive little attention. We must be conscious of the implied and explicit contracts we agree to, as information we produce and consume is increasingly mediated through technology. Similarly, as companies develop vertical integration business models, they enter into media production, delivery, storage and playback. These business models create the temptation to start creating to their own content, and perhaps give preferential treatment to their internally produced media. (Amazon also has plans to produce and broadcast an Internet show with Bill Maher and various guests.) Both Amazon and Blu-Ray HD-DVD are just current examples content being tied to proprietary hardware. If information wants to be free, perhaps part of that freedom involves being independent from hardware and software.

quoting a quote

Bud Parr, author of the blog Chekhov’s Mistress and commenter on if:book, recently posted on a speech given by Susan Sontag, entitled “Literature is Freedom.”

Quoting, his favorite quote:

A writer, I think, is someone who pays attention to the world. That means trying to understand, take in, connect with, what wickedness human beings are capable of; and not be corrupted – made cynical, superficial – by this understanding.

Literature can tell us what the world is like.

Literature can give us standards and pass on deep knowledge, incarnated in language, in narrative.

Literature can train, and exercise, our ability to weep for those who are not us or ours.

At the institute, we often describe the “book” as both a vessel (technology) and text (information) especially as we work on revising our mission statement. Even so, and only speaking for myself, it is still very easy to get caught up in things like networks, copyright policy, and Web 2.0, which are, of course, all important topics. Sontag’s quote is a good reminder of not just what resides in the vessel of the book, but why its contents are valuable.

an argument for net neutrality

Ten years after the initial signing of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, Congress is considering amending it. The original intention of the legislation was to increase competition by deregulating the telecommunication industry. The effects were gigantic, with a main result being that Regional Baby Operating Companies (RBOCs or Baby Bells) formed after the break up of the Ma Bell in 1984, merged into a handful of companies. Verzion nee Bell Atlantic, GTE, and NYNEX. SBC nee Southwestern Bell, PacTel, and Ameritech. Only now, these handful of companies operate with limited regulation.

On Tuesday, Congress heard arguments on the future of pricing broadband access. The question at hand is net neutrality, which is the idea that data transfer should have a single price, regardless of the provider, type or content of media being downloaded or uploaded. Variable pricing would have an effect on Internet companies as Amazon.com that use broadband networks for distributing their services as well as individuals. Cable companies and telecos such as Verizon, Comcast, Bell South, and AT&T are now planing to roll out tiered pricing. Under these new schemes, fees would be higher access to high-speed networks or certain services as downloading movies. Another intention is to charge different rates for downloading email, video, or games.

The key difference between opponents and proponents of net neutrality is their definition of innovation, and who benefits from that innovation. The broadband providers argue that other companies benefit from using their data pipes. They claim that by not being able to profit more from their networks, their incentive to innovate, that is, upgrade their systems, will decrease. While on the other side, firms as Vonage and Google argue the opposite, that uniform access spurs innovation, in terms of novel uses for the network. These kinds of innovations (video on demand) provide useful new services for the public, and in turn increase demand for the broadband providers.

First, it is crucial to point that all users are paying for access now. Sen. Byron Dorgan of North Dakota noted:

First, it is crucial to point that all users are paying for access now. Sen. Byron Dorgan of North Dakota noted:

”It is not a free lunch for any one of these content providers. Those lines and that access is being paid for by the consumer.”

Broadband providers argue that tiered pricing (whether for services or bandwidth) will increase innovation. This argument is deeply flawed. Tier-pricing will not guarntee new and useful services for users, but it will guarantee short term financial gains for the providers. These companies did not invent the Internet nor did they invent the markets for these services. Innovative users (both customers and start-ups) discovered creative ways to use the network. The market for broadband (and the subsequent network) exists because people outgrew the bandwidth capacity of dial-up, as more companies and people posted multimedia on the web. Innovation of this sort creates new demands for bandwidth and increases the customer base and revenue for the broadband providers. New innovative uses generally demand more bandwidth, as seen in p2p, video google, flickr, video ipods, and massively multiplayer online role playing games.

Use of the internet and the WWW did not explode for the mainstream consumer until ISPs as AOL moved to a flat fee pricing structure for their dial-up access. Before this period, most of the innovation of use came from the university, not only researchers, but students who had unlimited access. For these students, they ostensibly paid a flat fee what was embedded in their tuition. The low barrier of access in the early 1990s was essential in the creation of a culture of use that established the current market for Internet services that these broadband providers currently hope to restructure in price.

Prof. Eric Von Hippel of MIT’s Sloan School of Management, author of the book, Democratizing Innovation, has done extensive research on innovation. He has found that users innovation a great deal, and much of it is underreported by the industries that capitalize on these improvements to their technology. An user innovator tends to have one great innovation. Therefore, a fundamental requirement for user innovation is offering access to the largest possible audience. In this context, everyone can benefit from net neutrality.

Prof. Eric Von Hippel of MIT’s Sloan School of Management, author of the book, Democratizing Innovation, has done extensive research on innovation. He has found that users innovation a great deal, and much of it is underreported by the industries that capitalize on these improvements to their technology. An user innovator tends to have one great innovation. Therefore, a fundamental requirement for user innovation is offering access to the largest possible audience. In this context, everyone can benefit from net neutrality.

Tiered-pricing proponents argue that charging customers with limited download needs the same rates is unfair. This idea does not consider that the under-utilizers benefit overall from the innovations created by the over-utilizers. In a way, the under-utitlizers subsidize research for services they may use in the future. For example, the p2p community has created proven models and markets of sharing (professional or amateur) movies before the broadband providers (who also strive to become content providers.)

Maintaining democratic access will only fuel innovation, which will create new uses and users. New users translates into growing revenue for the broadband services. These new demands will also create an economic incentive to upgrade and maintain broadband providers’ networks. The key questions that Congress needs to ask itself, is who had been doing the most innovation in the last twenty years and what supported that innovation?

rethinking copyright: learning from the pro sports?

As Ben has reported, the Economics of Open Content conference spent a good deal of time discussing issues of copyright and fair use. During a presentation, David Pierce from Copyright Services noted that the major media companies are mainly concerned about protecting their most valuable assets. The obvious example is Disney’s extreme vested interest in protecting the Mickey Mouse, now 78 years old, from entering the public domain. Further, Pierce mentioned that these media companies fight to extend the copyright protection of everything they own in order to protect their most valuable assets. Finally, he stated that only a small portions of their total film libraries are available to consumers. Many people in attendance were intrigued by these ideas, including myself and Paul Courant from the University of Michigan. Earlier in the conference, Courant explained that 90-95% of UM’s library is out of print, and presumably much of that is under copyright protection.

If this situation is true, then, staggering amounts of media are being kept from the public domain or are closed from licensing for little or no reason. A little further thinking quickly leads to alternative structures of copyright that would move media into the public domain or at the least increase its availability, while appeasing the media conglomerates economic concerns.

Rules controlling the protection of assets is nothing new. For instance, in US professional sports, fairly elaborate structures are in place determine how players can be traded. Common sense dictates that teams cannot stockpile players from other teams. In the free agency era of the National Football League, teams have limited rights to control players from signing with other teams. Each NFL team can designate a single athlete as a “franchise” player, according to the current Collecting Bargaining Agreement with the player union. This designation gives them exclusive rights in retaining their player from competing offers. Similarly, in the National Basketball Association, when the league adds a new team, existing teams are allowed to protect eight players from being drafted and signed from the expansion team(s). What can we learn from these institutions? The examples show hoarding players is not good for sports, similarly hoarding assets is not in the best interest of the public good either.

The sports example has obviously limitations. In the NBA, team rosters are limited to fifteen players. On the other hand, a media company can hold an unlimited number of assets. In turn, applying this model would allow companies to seek extensions to only a portion of their copyright assets. Defining this proportion would certainly be difficult. For instance, it is still unclear to me how this might adapt to owners of one copyrighted property.

Another variant interpretation of this model would be to move the burden of responsibility back to the copyright holder. Here, copyright holders must show active economic use and value from these properties. This strategy would force media companies to make their archives available or put the media into the public domain. These copyright holders need to overcome their fears of flooding the markets and dated claims of limited shelf space, which are simply not relevant in the digital media / e-commerce age. Further, media companies would be encouraged to license their holdings for derivatives works, which would in fact lead to more profits. In that, these implementations would increase revenue by challenging the current shortsighted marketing decisions which fail to account for the long tail economic value of their holdings. Although these materials would not enter the public domain, they would be become accessible.

Would this block innovation? Creators of content will still be able to profit from their work for decades. When limited copyright did exist in its original implementation, creative innovation was certainly not hindered. Therefore, the argument that limiting protection of all of a media company’s assets in perpetuity would slow innovation is baseless. By the end of the current time copyright period, holders have ample time to extract value from those assets. In fact, infinite copyright protection slows innovation by removing incentives to create new intellectual property.

Finally, few last comments are worth noting. These models are, at best, compromises. I present them because the current state of copyright protection and extensions seems headed towards former Motion Pictures Association of America President Jack Valenti’s now infamous suggestion of extending copyright to “forever less a day.” Although these media companies have a huge financial stake in controlling these copyrights, I cannot overemphasize our Constitutional right to place these materials in the public domain. Article I, Section 8, clause 8 of the United States Constitution states:

Congress has the power to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Rights to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

Under these proposed schemes, fair use becomes even more cruical. Conceding that the extraordinary preciousness of intellectual property as Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny supersedes rights found in our Constitution implies a similarly extraordinary importance of these properties to our culture and society. Thus, democratic access to these properties for use in education and critical discourse must be equally imperative to the progress of culture and society. In the end, the choice, as a society, is ours. We do not need to concede anything.