Somebody interviewed Bob for a documentary a few months ago. I don’t remember who this was, because I was in the other room busy with something else, but I was half-listening to what was being discussed: how the book is changing, what precisely the Institute does, in short, what we discuss from day to day on this blog. One statement captured my ear: Bob offhandedly declared that “we don’t really know how to read Wikipedia yet”. I made a note of it at the time; since then I’ve been periodically pulling his statement out at idle moments and rolling it over and over in my mind like a pebble in my pocket, trying to decide exactly what it could mean.

Somebody interviewed Bob for a documentary a few months ago. I don’t remember who this was, because I was in the other room busy with something else, but I was half-listening to what was being discussed: how the book is changing, what precisely the Institute does, in short, what we discuss from day to day on this blog. One statement captured my ear: Bob offhandedly declared that “we don’t really know how to read Wikipedia yet”. I made a note of it at the time; since then I’ve been periodically pulling his statement out at idle moments and rolling it over and over in my mind like a pebble in my pocket, trying to decide exactly what it could mean.

There’s something appealing to me about the flatness of the statement: “We don’t really know how to read Wikipedia yet.” It’s obvious but revelatory: the reason that we find the Wikipedia frustrating is that we need to learn how to read it. (By we I mean the reading public as a whole. Perhaps you have; judging from the arguments that fly back and forth, it would seem that the majority of us haven’t.) The problem is, of course, that so few people actually bother to state this sort of thing directly and then to unpack the repercussions of it.

What’s there to learn in reading the Wikipedia? Let’s start with a sample sentence from the entry on Marcel Proust:

In addition to the grief that attended his mother’s death, Proust’s life changed due to a very large inheritance (in today’s terms, a principal of about $6 million, with a monthly income of about $15,000).

Criticizing the Wikipedia for being poorly written is like shooting fish in a barrel, but bear with my lack of sportsmanship for a second. Imagine that you found the above sentence in a printed reference work. A printed reference book that seems to be written in the voice of a sixth grade student deeply interested in matters financial might worry you. It would worry me. It’s worried many critics of the Wikipedia, who point out that this clearly isn’t the sort of manicured prose we’re used to reading in books and magazines.

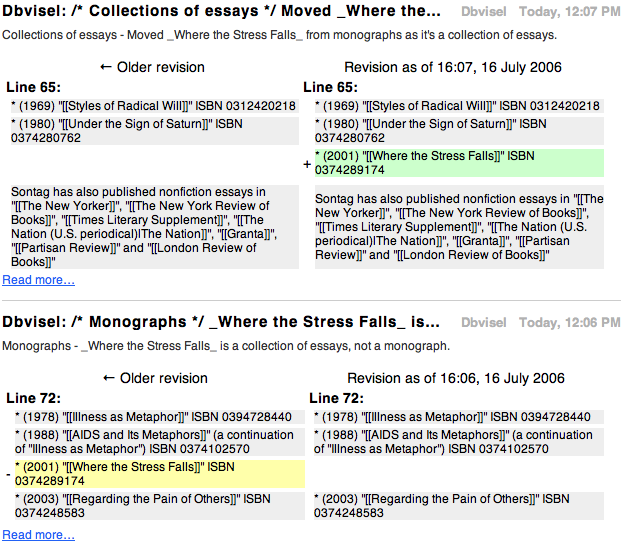

But this prose is also conceptually different. A Wikipedia article is not constructed in the same way that a magazine article is written. Nor is the content of a Wikipedia article at one particular instant in time – content that has probably been different, and might certainly change – analogous to the content of a print magazine article, which is always, from the moment of printing, exactly the same. If we are to keep using the Wikipedia, we’ll have to get used to the solecisms endemic there; we’ll also need to readjust they way we give credence to media. (Right now I’m going to tiptoe around the issue of text and authority, which is of course an enormous can of worms that I’d prefer not to open right now.) But there’s a reason that the above quotation shouldn’t be that worrying: it’s entirely possible, and increasingly probable as time goes on, that when you click the link above, you won’t be able to find the sentence I quoted.

This faith in the long run isn’t an easy thing, however. When we read Wikipedia we tend to apply to it the standards of judgment that we would apply to a book or magazine, and it often fails by these standards, as might be expected. When we’re judging Wikipedia this way, we presuppose that we know what it is formally: that it’s the same sort of thing as the texts we know. This seems arrogant: why should we assume that we already know how to read something that clearly behaves differently from the text we’re used to? We shouldn’t, though we do: it’s a human response to compare something new to something we already know, but often when we do this, we miss major formal differences.

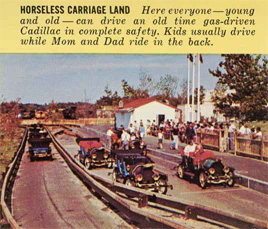

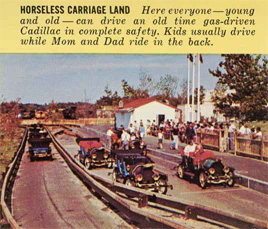

This isn’t the best way to read something new. It’s akin to the “horseless carriage” analogy that Ben’s used: when you think of a car as a carriage without a horse, you miss whatever it is that makes a car special. But there’s a problem with that metaphor, in that it carries with it ideas of displacement. Evolution is often perceived as being transformative: one thing turns into, and is then replaced by, another, as the horse was replaced by the car for purposes of transportation. But it’s usually more of a splitting: there’s a new species as well as the old species from which it sprung. The old species may go extinct, or it may not. To finish that example: we still have horses.

This isn’t the best way to read something new. It’s akin to the “horseless carriage” analogy that Ben’s used: when you think of a car as a carriage without a horse, you miss whatever it is that makes a car special. But there’s a problem with that metaphor, in that it carries with it ideas of displacement. Evolution is often perceived as being transformative: one thing turns into, and is then replaced by, another, as the horse was replaced by the car for purposes of transportation. But it’s usually more of a splitting: there’s a new species as well as the old species from which it sprung. The old species may go extinct, or it may not. To finish that example: we still have horses.

Figuratively, what’s happened with the Wikipedia is that a new species of text has arisen and we’re still wondering why it won’t eat the apples we’re proffering it. The Wikipedia hasn’t replaced print encyclopedias; in all probability, the two will coexist for a while. But I don’t think we yet know how to read Wikipedia. We judge it by what we’re used to, and everyone loses. Were you to judge a car by a horse’s attributes, you wouldn’t expect to have an oil crisis in a century.

Perhaps a useful way to think about this: a few paragraphs of Proust, found on a trip through In Search of Lost Time with Bob’s statement bouncing around my head. The Guermantes Way, the third part of the book, feels like the longest: much of this volume is about failing to recognize how things really are. Proust’s hapless narrator alternately recognizes his own mistakes of judgment and makes new ones for six hundred pages, with occasional flashes of insight, like this reflection:

. . . . There was a time when people recognized things easily when they were depicted by Fromentin and failed to recognize them at all when they were painted by Renoir.

. . . . There was a time when people recognized things easily when they were depicted by Fromentin and failed to recognize them at all when they were painted by Renoir.

Today people of taste tell us that Renoir is a great eighteenth-century painter. But when they say this they forget Time, and that it took a great deal of time, even in the middle of the nineteenth century, for Renoir to be hailed as a great artist. To gain this sort of recognition, an original painter or an original writer follows the path of the occultist. His painting or his prose acts upon us like a course of treatment that is not always agreeable. When it is over, the practitioner says to us, “Now look.” And at this point the world (which was not created once and for all, but as often as an original artist is born) appears utterly different from the one we knew, but perfectly clear. Women pass in the street, different from those we used to see, because they are Renoirs, the same Renoirs we once refused to see as women. The carriages are also Renoirs, and the water, and the sky: we want to go for a walk in a forest like the one that, when we first saw it, was anything but a forest – more like a tapestry, for instance, with innumerable shades of color but lacking precisely the colors appropriate to forests. Such is the new and perishable universe that has just been created. It will last until the next geological catastrophe unleashed by a new painter or writer with an original view of the world.

(The Guermantes Way, pp.323–325, trans. Mark Treharne.) There’s an obvious comparison to be made here, which I won’t belabor. Wikipedia isn’t Renoir, and its entry for poor Eugène Fromentin, whose paintings are probably better left forgotten, is cribbed from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. But like the gallery-goers who needed to learn to look at Renoir, we need to learn to read Wikipedia, to read it as a new form that certainly inherits some traits from what we’re used to reading, but one that differs in fundamental ways. That’s a process that’s going to take time.

I’ll write up what happened on the second day of Wikimania soon – I saw a lot of talks about education – but a quick observation for now. Brewster Kahle delivered a speech after lunch entitled “Universal Access to All Knowledge”, detailing his plans to archive just about everything ever & the various issues he’s confronted along the way, not least Jack Valenti. Kahle learned from Valenti: it’s important to frame the terms of the debate. Valenti explained filesharing by declaring that it was Artists vs. Pirates, an obscuring dichotomy, but one that keeps popping up. Kahle was happy that he’d succeeded in creating a catch phrase in naming “orphan works” – a term no less loaded – before the partisans of copyright could.

I’ll write up what happened on the second day of Wikimania soon – I saw a lot of talks about education – but a quick observation for now. Brewster Kahle delivered a speech after lunch entitled “Universal Access to All Knowledge”, detailing his plans to archive just about everything ever & the various issues he’s confronted along the way, not least Jack Valenti. Kahle learned from Valenti: it’s important to frame the terms of the debate. Valenti explained filesharing by declaring that it was Artists vs. Pirates, an obscuring dichotomy, but one that keeps popping up. Kahle was happy that he’d succeeded in creating a catch phrase in naming “orphan works” – a term no less loaded – before the partisans of copyright could.