One of the most interesting things about the emerging online forms of discourse is how they manage to tear open all our old assumptions. Even if new media hasn’t yet managed to definitively change the rules, it has put them into contention. Here’s one, presented as a rhetorical question: why do we bother to finish things?

The importance of process is something that’s come up again and again over the past two years at the Institute. Process, that is, rather than the finished work. Can Wikipedia ever be finished? Can a blog be finished? They could, of course, but that’s not interesting: what’s fascinating about a blog is its emulation of conversation, it’s back-and-forth nature. Even the unit of conversation – a post on a blog, say – may never really be finished: the author can go back and change it, so that the post you viewed at six o’clock is not the post you viewed at four o’clock. This is deeply frustrating to new readers of blogs; but in time, it becomes normal.

* * * * *

But before talking about new media, let’s look at old media. How important is finishing things historically? If we look, there’s a whole tradition of things refusing to be finished. We can go back to Tristram Shandy, of course, at the very start of the English novel: while Samuel Richardson started everything off by rigorously trapping plots in fixed arcs made of letters, Laurence Sterne’s novel, ostensibly the autobiography of the narrator, gets sidetracked in cock and bull stories and disasters with windows, failing to trace his life past his first year. A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy, Sterne’s other major work of fiction, takes the tendency even further: the narrative has barely made it into France, to say nothing of Italy, before it collapses in the middle of a sentence at a particularly ticklish point.

There’s something unspoken here: in Sterne’s refusal to finish his novels in any conventional way is a refusal to confront the mortality implicit in plot. An autobiography can never be finished; a biography must end with its subject’s death. If Tristram never grows up, he can never die: we can imagine Sterne’s Parson Yorrick forever on the point of grabbing the fille de chambre‘s ———.

Henry James on the problem in a famous passage from The Art of the Novel:

Really, universally, relations stop nowhere, and the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally but to draw, by a geometry of his own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so. He is in the perpetual predicament that the continuity of things is the whole matter, for him, of comedy or tragedy; that this continuity is never, by the space of an instant or an inch, broken, or that, to do anything at all, he has at once intensely to consult and intensely to ignore it. All of which will perhaps pass but for a supersubtle way of pointing the plain moral that a young embroiderer of the canvas of life soon began to work in terror, fairly, of the vast expanse of that surface.

But James himself refused to let his novels – masterpieces of plot, it doesn’t need to be said – be finished. In 1906, a decade before his death, James started work on his New York Edition, a uniform selection of his work for posterity. James couldn’t resist the urge to re-edit his work from the way it was originally published; thus, there are two different editions of many of his novels, and readers and scholars continue to argue about the merits of the two, just as cinephiles argue about the merits of the regular release and the director’s cut.

This isn’t an uncommon issue in literature. One notices in the later volumes of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu that there are more and more loose ends, details that aren’t quite right. While Proust lived to finish his novel, he hadn’t finished correcting the last volumes before his death. Nor is death necessarily always the agent of the unfinished: consider Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. David M. Levy, in Scrolling Forward: Making Sense of Documents in the Digital Age, points out the problems with trying to assemble a definitive online version of Whitman’s collection of poetry: there were a number of differing editions of Whitman’s collection of poems even during his life, a problem compounded after his death. The Whitman Archive, created after Levy wrote his book, can help to sort out the mess, but it can’t quite work at the root of the problem: we say we know Leaves of Grass, but there’s not so much a single book by that title as a small library.

The great unfinished novel of the twentieth century is Robert Musil’s The Man without Qualities, an Austrian novel that might have rivaled Joyce and Proust had it not come crashing to a halt when Musil, in exile in Switzerland in 1942, died from too much weightlifting. It’s a lovely book, one that deserves more readers than it gets; probably most are scared off by its unfinished state. Musil’s novel takes place in Vienna in the early 1910s: he sets his characters tracing out intrigues over a thousand finished pages. Another eight hundred pages of notes suggest possible futures before the historical inevitability of World War I must bring their way of life to an utter and complete close. What’s interesting about Musil’s notes are that they reveal that he hadn’t figured out how to end his novel: most of the sequences he follows for hundreds of pages are mutually exclusive. There’s no real clue how it could be ended: perhaps Musil knew that he would die before he could finish his work.

* * * * *

The visual arts in the twentieth century present another way of looking at the problem of finishing things. Most people know that Marcel Duchamp gave up art for chess; not everyone realizes that when he was giving up art, he was giving up working on one specific piece, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. Duchamp actually made two things by this name: the first was a large painting on glass which stands today in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Duchamp gave up working on the glass in 1923, though he kept working on the second Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, a “book” published in 1934: a green box that contained facsimiles of his working notes for his large glass.

Duchamp, despite his protestations to the contrary, hadn’t actually given up art. The notes in the Green Box are, in the end, much more interesting – both to Duchamp and art historians – than the Large Glass itself, which he eventually declared “definitively unfinished”. Among a great many other things, Duchamp’s readymades are conceived in the notes. Duchamp’s notes, which he would continue to publish until his death in 1968, function as an embodiment of the idea that the process of thinking something through can be more worthwhile than the finished product. His notes are why Duchamp is important; his notes kickstarted most of the significant artistic movements of the second half of the twentieth century.

Duchamp’s ideas found fruit in the Fluxus movement in New York from the early 1960s. There’s not a lot of Fluxus work in museums: a good deal of Fluxus resisted the idea of art as commodity in preference to the idea of art as process or experience. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece is perhaps the most well known Fluxus work and perhaps exemplary: a performer sits still while the audience is invited to cut pieces of cloth from her (or his) clothes. While there was an emphasis on music and performance – a number of the members studied composition with John Cage – Fluxus cut across media: there were Fluxus films, boxes, and dinners. (There’s currently a Fluxus podcast, which contains just about everything.) Along the way, they also managed to set the stage for the gentrification of SoHo.

There was a particularly rigorous Fluxus publishing program; Dick Higgins helmed the Something Else Press, which published seminal volumes of concrete poetry and artists’ books, while George Maciunas, the leader of Fluxus inasmuch as it had one, worked as a graphic designer, cranking out manifestos, charts of art movements, newsletters, and ideas for future projects. Particularly ideas for future projects: John Hendricks’s Fluxus Codex, an attempt to catalogue the work of the movement, lists far more proposed projects than completed ones. Owen Smith, in Fluxus: The History of an Attitude, describes a particularly interesting idea, an unending book:

This concept developed out of Maciunas’ discussions with George Brecht and what Maciunas refers to in several letters as a “Soviet Encyclopedia.” Sometime in the fall of 1962, Brecht wrote to Maciunas about the general plans for the “complete works” series and about his own ideas for projects. In this letter Brecht mentions that he was “interested in assembling an ‘endless’ book, which consists mainly of a set of cards which are added to from time to time . . . [and] has extensions outside itself so that its beginning and end are indeterminate.” Although the date on this letter is not certain, it was sent after Newsletter No. 4 and prior to the middle of December when Maciunas responded to it.} This idea for a expandable box is later mentioned by Maciunas as being related to “that of Soviet encyclopedia – which means not a static box or encyclopedia but a constantly renewable – dynamic box.”

Maciunas and Brecht never got around to making their Soviet encyclopedia, but it’s an idea that might resonate more now than in did in 1962. What they were imagining is something that’s strikingly akin to a blog. Blogs do start somewhere, but most readers of blogs don’t start from the beginning: they plunge it at random and keep reading as the blog grows and grows.

* * * * *

One Fluxus-related project that did see publication was An Anecdoted Topography of Chance, a book credited to Daniel Spoerri, a Romanian-born artist who might be best explained as a European Robert Rauschenberg if Rauschenberg were more interested in food than paint. The basis of the book is admirably simple: Spoerri decided to make a list of everything that was on his rather messy kitchen table one morning in 1961. He made a map of all the objects on his not-quite rectangular table, numbered them, and, with the help of his friend Robert Filliou, set about describing (or “anecdoting”) them. From this simple procedure springs the magic of the book: while most of the objects are extremely mundane (burnt matches, wine stoppers, an egg cup), telling how even the most simple object came to be on the table requires bringing in most of Spoerri’s friends & much of his life.

Having finished this first version of the book (in French), Spoerri’s friend Emmett Williams translated into English. Williams is more intrusive than most translators: even before he began his translation, he appeared in a lot of the stories told. As is the case with any story, Williams had his own, slightly different version of many of the events described, and in his translation Williams added these notes, clarifying and otherwise, to Spoerri’s text. A fourth friend, Dieter Roth, translated the book into German, kept Williams’s notes and added his own, some as footnotes of footnotes, generally not very clarifying, but full of somewhat related stories and wordplay. Spoerri’s book was becoming their book as well. Somewhere along the line, Spoerri added his own notes. As subsequent editions have been printed, more and more notes accrete; in the English version of 1995, some of them are now eight levels deep. A German translation has been made since then, and a new French edition is in the works, which will be the twelfth edition of the book. The text has grown bigger and bigger like a snowball rolling downhill. In addition to footnotes, the book has also gained several introductions, sketches of the objects by Roland Topor, a few explanatory appendices, and an annotated index of the hundreds of people mentioned in the book.

Part of the genius of Spoerri’s book is that it’s so simple. Anyone could do it: most of us have tables, and a good number of those tables are messy enough that we could anecdote them, and most of us have friends that we could cajole into anecdoting our anecdotes. The book is essentially making something out of nothing: Spoerri self-deprecatingly refers to the book as a sort of “human garbage can”, collecting histories that would be discarded. But the value of of the Topography isn’t rooted in the objects themselves, it’s in the relations they engender: between people and objects, between objects and memory, between people and other people, and between people and themselves across time. In Emmett Williams’s notes on Spoerri’s eggshells, we see not just eggshells but the relationship between the two friends. A network of relationships is created through commenting.

George LeGrady seized on the hypertextual nature of the book and produced, in 1993, his own Anecdoted Archive of the Cold War. (He also reproduced a tiny piece of the book online, which gives something of a feel for its structure.) But what’s most interesting to me isn’t how this book is internally hypertextual: plenty of printed books are hypertextual if you look at them through the right lens. What’s interesting is how its internal structure is mirrored by the external structure of its history as a book, differing editions across time and language. The notes are helpfully dated; this matters when you, the reader, approach the text with thirty-odd years of notes to sort through, notes which can’t help being a very slow, public conversation. There’s more than a hint of Wikipedia in the process that underlies the book, which seems to form a private encyclopedia of the lives of the authors.

And what’s ultimately interesting about the Topography is that it’s unfinished. My particular copy will remain an autobiography rather than a biography, trapped in a particular moment in time: though it registers the death of Robert Filliou, those of Dieter Roth and Roland Topor haven’t yet happened. Publishing has frozen the text, creating something that’s temporarily finished.

* * * * *

We’re moving towards an era in which publishing – the inevitable finishing stroke in most of the examples above – might not be quite so inevitable. Publishing might be more of an ongoing process than an event: projects like the Topography, which exists as a succession of differing editions, might become the norm. When you’re publishing a book online, like we did with Gamer Theory, the boundaries of publishing become porous: there’s nothing to stop you from making changes for as long as you can.

Jorge Luis Borges tells the story of “Funes, the Memorious,” a man from Uruguay who, after an accident, finds himself blessed with perfect memory. Ireneo Funes remembers everything that he encounters; he can forget nothing that he’s seen or heard, no matter how minor. As one might expect, this blessing turns out to be a curse: overwhelmed by his impressions of the world, Funes can’t leave his darkened room. Worse, he can’t make sense of the vast volume of his impressions by classifying them. Funes’s world is made up entirely of hapax legomena. He has no general concepts:

Jorge Luis Borges tells the story of “Funes, the Memorious,” a man from Uruguay who, after an accident, finds himself blessed with perfect memory. Ireneo Funes remembers everything that he encounters; he can forget nothing that he’s seen or heard, no matter how minor. As one might expect, this blessing turns out to be a curse: overwhelmed by his impressions of the world, Funes can’t leave his darkened room. Worse, he can’t make sense of the vast volume of his impressions by classifying them. Funes’s world is made up entirely of hapax legomena. He has no general concepts: (p. 136 in Andrew Hurley’s translation of Collected Fictions.) Funes dies prematurely, alone and unrecognized by the world; while we are told that he died of “pulmonary congestion,” it’s clear that Funes has drowned in his memories. While there are advantages to remembering everything, Borges’s narrator realizes his superiority to Funes:

(p. 136 in Andrew Hurley’s translation of Collected Fictions.) Funes dies prematurely, alone and unrecognized by the world; while we are told that he died of “pulmonary congestion,” it’s clear that Funes has drowned in his memories. While there are advantages to remembering everything, Borges’s narrator realizes his superiority to Funes: (p. 137) Borges’s story isn’t really about memory as much as it is about how we make sense of the world. It’s important to forget things, to ignore the minor differences between similar objects. We recognize that the dog the Funes sees at three-fourteen and the dog that he sees at three-fifteen are the same; Funes does not. Funes dies insane; we, hopefully, do not.

(p. 137) Borges’s story isn’t really about memory as much as it is about how we make sense of the world. It’s important to forget things, to ignore the minor differences between similar objects. We recognize that the dog the Funes sees at three-fourteen and the dog that he sees at three-fifteen are the same; Funes does not. Funes dies insane; we, hopefully, do not. I won’t pretend to be the first to see in the Internet parallels to the all-remembering mind of Funes; a book could be written, if it hasn’t already been, on how Borges invented the Internet. It’s interesting, however, to see that the problems of Funes are increasingly everyone’s problems. As humans, we forget by default; maybe it’s the greatest sign of the Internet’s inhumanity that it remembers. With time things become more obscure on the Internet; you might need to plumb the Wayback Machine at archive.org rather than Google to find a website from 1997. History becomes obscure, but it only very rarely disappears entirely on the Internet.

I won’t pretend to be the first to see in the Internet parallels to the all-remembering mind of Funes; a book could be written, if it hasn’t already been, on how Borges invented the Internet. It’s interesting, however, to see that the problems of Funes are increasingly everyone’s problems. As humans, we forget by default; maybe it’s the greatest sign of the Internet’s inhumanity that it remembers. With time things become more obscure on the Internet; you might need to plumb the Wayback Machine at archive.org rather than Google to find a website from 1997. History becomes obscure, but it only very rarely disappears entirely on the Internet. A recent working paper by Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, recognizes the problems of the Internet’s elephantine memory. He suggests pre-emptively dealing with the issues that are sure to spring up in the future by actively building forgetting into the systems that comprise the network. Mayer-Schoenberger envisions that some of this forgetting would be legally enforced: commercial sites might be required to state how long they will keep customer’s information, for example.

A recent working paper by Viktor Mayer-Schoenberger, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, recognizes the problems of the Internet’s elephantine memory. He suggests pre-emptively dealing with the issues that are sure to spring up in the future by actively building forgetting into the systems that comprise the network. Mayer-Schoenberger envisions that some of this forgetting would be legally enforced: commercial sites might be required to state how long they will keep customer’s information, for example.  It’s an interesting proposal, if firmly in the realm of the theoretical: it’s hard to imagine that the public will be proactive enough about this issue to push the government to take issue any time soon. Give it time, though: in a decade, there will be a generation dealing with embarrassing ten-year-old MySpace photos. Maybe we’ll no longer be embarrassed about our pasts; maybe we won’t trust anything on the Internet at that point; maybe we’ll demand mandatory forgetting so that we don’t all go crazy.

It’s an interesting proposal, if firmly in the realm of the theoretical: it’s hard to imagine that the public will be proactive enough about this issue to push the government to take issue any time soon. Give it time, though: in a decade, there will be a generation dealing with embarrassing ten-year-old MySpace photos. Maybe we’ll no longer be embarrassed about our pasts; maybe we won’t trust anything on the Internet at that point; maybe we’ll demand mandatory forgetting so that we don’t all go crazy.

But a partial fulfillment for my desire to have a portable Wikipedia has come along: Matt Swann has

But a partial fulfillment for my desire to have a portable Wikipedia has come along: Matt Swann has  To my mind, browsing is one of the primary virtues of a print encyclopedia: the arbitrary logic of alphabetization makes for a serendipitous reading experience, and you often come away from a print encyclopedia having read something in a nearby article that you didn’t intend to read. This is something that’s generally lost with online reference works: links between articles are supposed to make logical sense. This is also a reflection of our reading behavior: if I search for “book” in Wikipedia, I’m probably looking for something in particular. If I’m interested in book conservation issues, I might click on the link for

To my mind, browsing is one of the primary virtues of a print encyclopedia: the arbitrary logic of alphabetization makes for a serendipitous reading experience, and you often come away from a print encyclopedia having read something in a nearby article that you didn’t intend to read. This is something that’s generally lost with online reference works: links between articles are supposed to make logical sense. This is also a reflection of our reading behavior: if I search for “book” in Wikipedia, I’m probably looking for something in particular. If I’m interested in book conservation issues, I might click on the link for  The experience of reading Wikipedia this way isn’t perfect: many links don’t work, and some articles seem to arbitrarily end, some in mid-sentence, some in mid-word. You also realize how many links in Wikipedia aren’t useful at all. If I’m interested in books as a concept, I’m probably not interested in

The experience of reading Wikipedia this way isn’t perfect: many links don’t work, and some articles seem to arbitrarily end, some in mid-sentence, some in mid-word. You also realize how many links in Wikipedia aren’t useful at all. If I’m interested in books as a concept, I’m probably not interested in

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a  A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise:

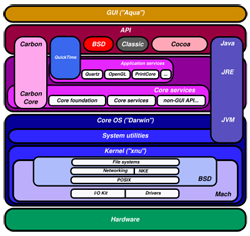

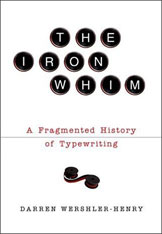

A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise:  There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.

There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.