- In Mute, Tony D. Sampson reviews FLOSS+ART and Software Studies: A Lexicon, two books on software studies and digital art.

- At the Poetry Foundation, Stephanie Strickland a manifesto for e-poetry, which nicely defines how e-poetry might differ from traditional poetry. Examples are provided, though most aren’t very compelling.

- Richard Kostelanetz, who has a long history in visual poetry, has some Flash-based e-poetry in Little Red Leaves. He’s also part of a concert put on by the Electronic Music Foundation at Judson Church in New York on February 27.

- The current issue of Episteme focuses on the “epistemology of mass collaboration”; Larry Sanger, formerly of Wikipedia and currently of Citizendium, has an article about Wikipedia and expertise, one of the chief causes of his falling out with Wikipedia.

Author Archives: dan visel

announcement: itin film on sunday

Alex Itin, the Institute’s artist-in-residence, currently has a show up in Frost Space in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. If you’re around this Sunday afternoon, he’s screening his films and giving an artist’s talk. I’m not sure exactly what he’ll be up to – Alex is nothing if not unpredictable – but it will certainly be interesting and entertaining.

wikipedia before wikipedia

I’ve been reading Tom McArthur’s Worlds of Reference: lexicography, learning and language from the clay tablet to the computer, a history of dictionaries, encyclopedias and reference materials published in 1986. The last section, titled “Tomorrow’s World” is interesting in hindsight: having looked at the major shifts that have occurred in how cultures have used lexicography, McArthur is aware that things change in unimaginable ways. He shies away from making detailed predictions about how the computer will change the dictionary or the encyclopedia; but he does find an interesting model for how the collaborative creation of knowledge might work in the future. Because I haven’t seen this mentioned online, I’ll quote this at length:

. . . I am considering something much more radically interesting: turning students on occasion into once-in-a-lifetime Sam Johnsons and Noah Websters.

At least one remarkable precedent exists for this idea: a project undertaken between 1978 and 1982 on the lower East Side of New York City which produced a “Trictionary” without a single really-truly lexicographer being involved.

The Trictionary is a 400-page trilingual English/Spanish/Chinese wordbook, covering a base vocabulary of some 3,000 items per language. Much of the basic cost was covered by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the bulk of the work was done on the premises of the Chatham Square branch of the New York Public Library, on East Broadway. The librarian there, Virginia Swift, was glad to provide the accommodation, while the original idea was developed by Jane Shapiro, a teacher of English as a Second Language at Junior High School 65, helped through all the stages the work by Mary Scherbatoskoy of ARTS (Art Resources for Teachers and Students). They organized the work, but they were not the compilers as such.

The compilation was done, as The New Yorker reports (10 May 1982) “by the spare-time energy of some 150 young people from the neighborhood”, aged between 10 and 15, two afternoons a week over three years. New York is the multilingual city par excellence, in which, as the report points out, “some of its citizens live in a kind of linguistic isolation, islanded in their languages”. The Trictionary was an effort to do something about that kind of isolation and separateness. One method used in the project was getting together a group of youngsters variously skilled in English, Spanish and Chinese and “brainstorming” over, say, the word ANIMALS written on an otherwise empty blackboard. They would think of animals and considered how they were labelled in each language, putting their triples on the board and arguing about the legitimacy of particular terms. Another method was the review session, a more sophisticated activity where a stack of blue cards with English words on them was used to create equivalent stacks in pink for Spanish and yellow for Chinese. It was out of this kind of interactive effort that the Trictionary developed, until in its final form it had a blue section with English first, a second section that was yellow and Chinese, and a third section that was pink and Spanish. Each part had three columns per page, with each language appropriately presented. In all three sections, the material was punctuated here and there by line drawings done by the youngsters themselves.

Jane Shapiro told The New Yorker that when she first went to work in the area she had had no idea what the language situation was like. The neighbourhood is about 80% Chinese and 20% Spanish-speaking, and in class she had often found herself in the position of comparing all three languages. Out of that “small United Nations” came the idea for the book, because she had often wished for such a book, but of course no right-minded publisher had ever thought of that particular combination as commercially viable or academically interesting. Additionally, and damningly, Shapiro felt that what dictionaries were available “were either too stiff or out of date or written on a linguistic level far different from that of the students”. In other words, because formal lexicography had nothing to offer, grass-roots lexicography had to serve instead.

As with Vaugelas, neighbourhood usage was the authority, and as work progressed the women and their charges actually kept away from published dictionaries so as to be sure that the words came from the youngsters themselves. Reality also prevailed, in that there is a fair quantity of legal and medical terms in the book. These were included because the children often served as interpreters between their elders and lawyers and doctors. Motivation was high, despite a shifting population of helpers, evidently because the children could see the practical utility of what they were doing. One youngster engaged in the work was Iris Chu, born in Venezuela of Chinese parents and brought to New York about five years earlier. She told The New Yorker that she made a lot of friends while working on the Trictionary (the opposite to what often happens to lexicographers), adding: “It’s funny to see it as a book now – before, it was just something we did every week. I’m really sorry it’s over. For us, it was a whole lot of fun.”

It was also a prototype for a whole new kind of educational lexicography (with or without the additional advantage, where available, of electronic and other aids). The ancient Sumerians and the medieval Scholastics would have understood the general idea of the Trictionary very well, and Comenius would certainly have approved of it. I approve of it whole-heartedly because it simply broke the mould of conventional thinking. Additionally, we can see in the brain-storming sessions and the use of the cards the two modes of lexicography creatively at work side by side: themes and word relationships on one side, alphabetic order on the other. The women of the lower East Side certainly discovered a formula for getting the taxonomic urge working in ways that are just as spectacular as any instrument that beeps, blinks and hums.

(pp. 181–183.) There doesn’t seem to be much trace of the Trictionary online; a cursory search finds the New Yorker article that McArthur refers to (behind their paywall). The New York Center for Urban Folk Culture seems to be selling copies for $5; their page for the project gives it a minimal description and has images of some of the pages.

judging a book by its contents

There’s a post at the Harper Studio blog about Stephen King’s recent denigration of Stephenie Meyer’s talents as a writer. Meyer is, of course, the author of the Twilight books, a chaste vampire saga. The post asks:

Can a book be deemed “good” or “bad” based solely of the quality of its writing?

I haven’t read the Twilight books so I can’t weigh in on King’s assessment. But it seems to me that Stephenie Meyer has activated something profound in people- mostly teenage girls – and the ability to do that may be as rare as the literary gifts of a writer like… Stephen King. Put another way: In terms of literary merit, Twilight may not be “good,” but that doesn’t mean it’s not great.

I have not read these books, though people whose taste in writing I trust more than Stephen King’s have assured me that the writing is abysmal. I have been repeatedly entertained by having what goes on in these books described to me; I have also seen the movie based upon the first of them, which I found quite thoroughly astonishing. From my perspective, it seems clear that these books are a Jesse Helms-level assault on American morality. It’s tempting to pull out Theodor Adorno, bête noire of the blogosphere: should you need a fix, his miniature essay “Morality and Style”, from Minima Moralia, will do the trick nicely.

But I’m interested not so much in Twilight‘s merit but in the attitude toward books that’s on display in this post. Books can be many things, but by this argument they stand mostly as commodity: Twilight is culturally valuable not because of anything that it might be saying – or the method in which it’s said – but because it’s reached a lot of people. By this reductionist perspective, Twilight might as well be a movie or a videogame as a book. And I think it’s this sort of thinking which is causing the downfall of publishing: for big publishers, a great book is simply one that sells a lot of copies. This is an attitude which makes sense to the people in charge of the numbers at a big publishing house, but I’m not sure that it plays so well with consumers. I can’t imagine that anyone – beside their employees – would be particularly upset if Hachette (publishers of Twilight) goes under. If a book is just a vehicle for the consumer to get content as quickly as possible, another vehicle can easily be found.

correspondences

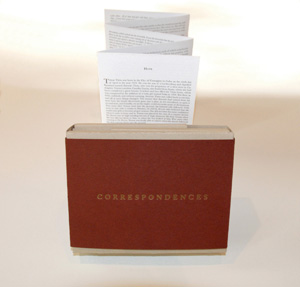

One of the most attractive books I picked up last year was a copy of Ben Greenman’s Correspondences, a collection of short stories published by Hotel St. George Press. Strictly speaking, you could argue that Correspondences isn’t a book: a maroon band surrounds an ingeniously constructed box which, when unfolded, turns out to contain three pamphlets folded accordion-style and a postcard, to which I’ll return. Each pamphlet is encircled by two stories, all of which share a theme of letter-writing. The whole thing was printed letterpress; it’s a limited edition, and each copy is signed by the author. Although it’s a relatively pricey book, I can’t imagine that the publisher’s making much money on it: clearly it cost a lot to make.

One of the most attractive books I picked up last year was a copy of Ben Greenman’s Correspondences, a collection of short stories published by Hotel St. George Press. Strictly speaking, you could argue that Correspondences isn’t a book: a maroon band surrounds an ingeniously constructed box which, when unfolded, turns out to contain three pamphlets folded accordion-style and a postcard, to which I’ll return. Each pamphlet is encircled by two stories, all of which share a theme of letter-writing. The whole thing was printed letterpress; it’s a limited edition, and each copy is signed by the author. Although it’s a relatively pricey book, I can’t imagine that the publisher’s making much money on it: clearly it cost a lot to make.

As a print book, Correspondences is very much of the present moment, inauspicious as it might be for print publishers. Hotel St. George hasn’t bothered with distribution in bookstores; the primary mode of distribution is HSG’s website. Ben Greenman has enough of a following that they’ll probably do well this way. The extraordinary form of the book is a recognition that in an age when content has become almost infinitely cheap an object needs to stand out to be bought. (One might analogously consider the CDs of Raster-Noton or Touch.) Appealing to the collector’s market makes sense for print publishing: all of Hotel St. George’s books are beautifully produced, but Correspondences takes their work to another level.

What’s most interesting to me about Ben Greenman’s book, however, is the postcard. As the box is opened, a seventh story, titled “What He’s Poised to Do,” is disclosed, printed on the box itself. A note from the author describes it as

the tale of a man who walks out on his marriage and reconsiders it from a distance. The man is staying in a hotel. While he is there, he writes ad receives a number of postcards. Some carry messages of love, others messages of regret, others still are confessions or rationalizations. There are nine postcard messages in all, not a single one of which is actually reprinted in the text of the story.

At nine points in the story there are bracketed numbers, indicating the points in the story where a postcard is read or sent; the reader is invited to take the postcard include and to compose a message to be a part of the story, and possibly part of future editions of the book. There’s a lovely tension here between the intent of the author and the wishes of the collector: filling out the postcard and dropping it in the mail destroys the unity of the book. The Mail Room at Hotel St. George’s website might convince the wary book-owner: on display are some postcards that have already been sent back. (One does note that a few of the postcard writers seem to have shied away from using the postcard that came with the book.)

The copy of Correspondences that I own – postcard still tucked in its flap – is precisely situated in time: it’s a book that prefigures its own destruction and, in a way, its own obsolescence. While this book is very firmly an object, it’s also aware of itself as a process: while the writing and the printing of the book has already happened, the reader’s response may yet happen. It’s a book that wouldn’t have existed in this form if the web hadn’t changed our understanding of how books work.

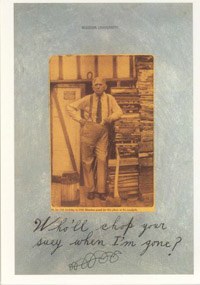

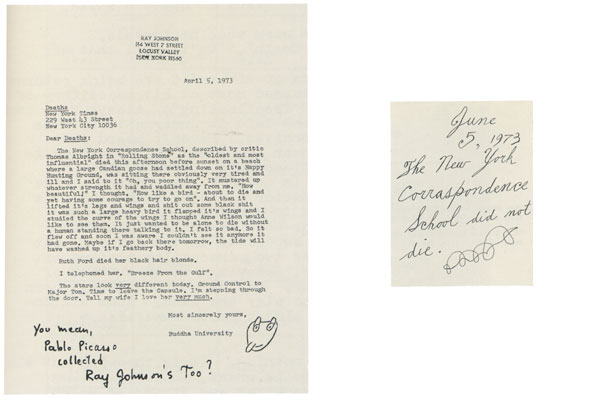

Ben Greenman’s postcard project might be seen as a recapitulation of themes present in the mail art of Ray Johnson. Trained at Black Mountain College as a painter, Johnson began making collages, which he sent to friends through the mail in the early 1950s; his use of the postal service quickly became a major focus of his art. Others followed his example; the movement he started was termed “mail art,” and it continues to this day. Although Johnson was well known and admired in the New York art world, much of his work operated outside the normal channels of the art world and he’s still surprisingly unknown to the general public. How to Draw a Bunny, John Walter’s 2002 documentary, is perhaps the easiest way in to the artist’s work. Interviews with Johnson’s friends and associates focus on the nature of their interactions with him; these interactions, it becomes clear, were as much a part of Johnson’s work as the work itself.

Ben Greenman’s postcard project might be seen as a recapitulation of themes present in the mail art of Ray Johnson. Trained at Black Mountain College as a painter, Johnson began making collages, which he sent to friends through the mail in the early 1950s; his use of the postal service quickly became a major focus of his art. Others followed his example; the movement he started was termed “mail art,” and it continues to this day. Although Johnson was well known and admired in the New York art world, much of his work operated outside the normal channels of the art world and he’s still surprisingly unknown to the general public. How to Draw a Bunny, John Walter’s 2002 documentary, is perhaps the easiest way in to the artist’s work. Interviews with Johnson’s friends and associates focus on the nature of their interactions with him; these interactions, it becomes clear, were as much a part of Johnson’s work as the work itself.

The mail was a primary method of communication for Johnson, particularly after he left New York City for Long Island in 1968; his death in 1995 came just at the cusp of broad use of the Internet to communicate. Mail art, he told James Rosenquist, was an extension of Cubism: he put things in the mail and they got spread all over the place. It was also an attempt to take art out of the commercial sphere, setting up a gift-based economy in its stead. The critic Ina Blom describes it in The Name of the Game: Ray Johnson’s Postal Performance as being

one of several art movements that tried to create an alternative space for art – a space that would be radically social and interactive, intermedial and performative. Mail art seemed to focus explicitly on the communicational aspects of both art production and reception, creating a huge network of correspondent who could communicate and exchange objects and messages through the postal system

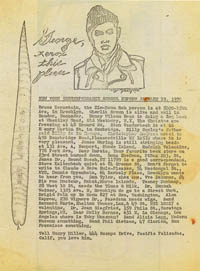

(p. 6.) Johnson ran what he called the New York Correspondence School; he used the word correspondence not simply for its reference to communication but for the way he made associations with words and graphic elements in his collages. Mailings were sent out, like this New York Correspondence School Report from January 19, 1970. William S. Wilson, in an essay entitled With Ray: The Art of Friendship, gives a sample of his working method:

(p. 6.) Johnson ran what he called the New York Correspondence School; he used the word correspondence not simply for its reference to communication but for the way he made associations with words and graphic elements in his collages. Mailings were sent out, like this New York Correspondence School Report from January 19, 1970. William S. Wilson, in an essay entitled With Ray: The Art of Friendship, gives a sample of his working method:

Walking on the Lower East Side Ray frequently saw a Ukrainian sign advertising a dance in letters which looked to him like “3-A-BABY”. He then equated “dance” with “three”, so that when three babies were involved with his life, he put the dance of three into the word “correspondence”, thereafter usually writing New York Correspondance School. Because Ray wanted to respond to accidents with spontaneities, he needed accidents to produce something more and other than he had planned to produce. In that spirit I showed him how he had happened to construct the French word,

correspondance, and gave him a copy of Baudelaire’s poem “Les Correspondances”. Later he improvised “corraspongence” and other permutations.

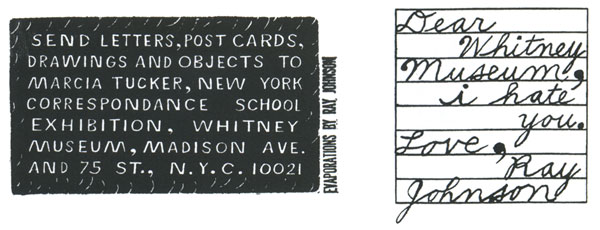

(p. 34) Membership was seemingly capricious and full of contradictions: members included institutions and the dead; the school committed suicide publicly at least once; and it was at best the most constant member of a baffling parade of clubs and organizations that Johnson ran, including, at random, Buddha University, the Deadpan Club, the Odilon Redon Fan Club, the Nancy Sinatra Fan Club. The Whitney Museum organized a show of the Correspondence School’s work, entitled Ray Johnson: New York Correspondance School in 1970; the museum exhibited everything Johnson’s network of collaborators mailed to it.

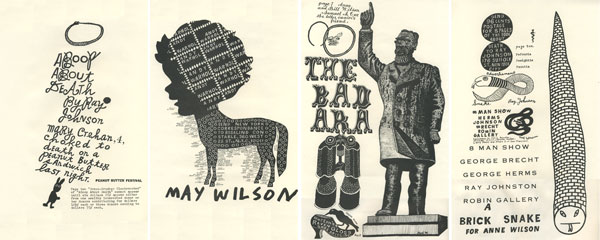

“The whole idea of the Correspondence School,” Johnson told Richard Bernstein in an interview with Andy Warhol’s Interview in August, 1972 “is to receive and dispense with these bits of information, because they all refer to something else. It’s just a way of having a conversation or exchange, a kind of social intercourse.” Emblematic of Johnson’s work might be his Book about Death, begun in 1963, which consisted of thirteen printed pages of collaged images and text, which were mailed individually to Clive Phillpot, chief librarian at the Museum of Modern Art, and others. (A few pages are reproduced below.) The Book about Death was discorporate, as befits a book about death; more than being unbound, Johnson made sure that none of his readers received a complete set of the pages of the book. The book could only be assembled and read in toto by the correspondents working in concert: it was a book that demanded active participation in its reading. The content as well as the form of the Book about Death request active participation: the names of his correspondents feature prominently in it, but understanding of what Johnson was doing with those names requires some knowledge of the people who had those names.

Much of Johnson’s work is interesting because it’s so dependent upon its audience. It’s not something that can exist under glass: rather, it’s a work that’s based upon personal relationships. Henry Martin writes about Ray Johnson’s work in a way that makes it sound like he’s talking about a social networking platform:

To me, Ray Johnson’s Correspondence School seems simply an attempt to establish as many significantly human relationships with as many individual people as possible. All of the relationships of which the School is made are personal relationship: relationships with a tendency towards intimacy: relationships where true experiences are truly shared and where what makes an experience true is its real participation in a secret libidinal charge. And the relationships that the artist values so highly are something he attempts to pass on to others. The classical exhortation in a Ray Johnson is “please send to . . . .” Person A will receive an object or an image and be asked to pass it on to person B, and the image will probably be appropriate to these two different people in two entirely different ways, or in terms of two entirely different chains of association. It thus becomes a kind of totem that can connect them, and whatever latent relationship may possibly exist between person A and person B becomes a little less latent and a little more real. It’s a beginning of an uncommon sense of community, and this sense of community grows as persons A and B send something back through Ray to each other, or through each other back to Ray.

(p. 186 in Ray Johnson: Correspondences.) Johnson’s work was about connection, the “art of friendship” as the title of Wilson’s essay has it. Work about personal connection has a necessarily uneasy relationship with the idea of art as a commodity; a great deal of Johnson’s work (including some of the pages of the Book about Death above) references money and remuneration in some way. Looked at through the lens of 2009, Johnson’s work seems remarkably prescient in its recognition of the importance of the network and the problems still inherent in it.

Who, if I cried out, would hear me? asks Rainer Maria Rilke at the start of the first Duino Elegy. It’s a rhetorical question that might be worth consideration: who does Rilke – or his speaker – think will hear him? Completing the line provides a superficial answer: “who” becomes someone “among the angels’ hierarchies”. But if the cry of Rilke’s speaker is directed at the angels, it’s heard by us, the readers of the poem: as a published work, the Duino Elegies function as a cry from a poet who desires to be heard. Rilke dedicated his poems to the Princess Marie von Thurn and Taxis-Hohenlohe, who brought him to Duino; she is perhaps the most proximate reader that Rilke expected. We are not the audience that Rilke envisioned; by now, everyone that Rilke might have reasonably expected to read his poem is dead.

Such authorial intent, if it existed, can’t stand in the way of the reader’s response. While reading is often a solitary act, a sense of connection can be engendered: a grieving reader might read Rilke’s poem and feel a sense of empathy, a commonality of experience. This is anticipated by Rilke’s poem (here in Stephen Mitchell’s translation):

Ah, whom can we ever turn to

in our need? Not angels, not humans,

and already the knowing animals are aware

that we are not really at home in

our interpreted world.

Rilke isn’t presumptuous enough to propose his own work as the answer to his question, though plenty of his readers would be happy to do just that. This empathy between the author and the reader is not empathy as empathy is generally understood to exist between two people: Rilke is of course dead and does not know the reader or the suffering that the reader might be undergoing. The reader may not even speak the same language as the author. Rilke is not your friend and almost certainly would not cheer you up if he were. But this is immaterial, the feeling still exists: the reader knows Rilke even if Rilke does not know the reader. To move from the specific to the overly general, this sort of response is perhaps why people describe themselves as having a visceral connection with books: our terror of print being dead isn’t so much for the books themselves but for the associations inherent in those physical objects, the sense of connection with the author even if that connection is unreciprocated.

The question of the audience of a book, and the connection of the audience to the author, is one that’s currently in a state of flux. Historically authors were something like mother sea turtles; publishing a book was something like laying eggs on a beach to hatch as they might: a reader might find a book, or a reader might not. An author could conceivably write a book for a single reader, but this doesn’t happen very often. A reader could, in the days before the Internet, find the author’s contract information from the publisher and write a letter to the author, but that happened comparatively rarely. The relationship between readers and authors is different now: after reading Greenman’s book I emailed him wondering if he’d been influenced by Ray Johnson’s work – no, he said – a behavior I find myself indulging in more and more lately. Greenman’s work, like that of Johnson’s before him, anticipates a new kind of relation between the author and the reader. The reworking of this relationship in increasingly varied ways will be the most significant aspect of the way our reading changes as it moves from the printed page to the networked screen.

a step forward for creative commons

Peter Brantley points out what’s now at http://www.whitehouse.gov/copyright/:

Pursuant to federal law, government-produced materials appearing on this site are not copyright protected. The United States Government may receive and hold copyrights transferred to it by assignment, bequest, or otherwise.

Except where otherwise noted, third-party content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Visitors to this website agree to grant a non-exclusive, irrevocable, royalty-free license to the rest of the world for their submissions to Whitehouse.gov under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Congratulations to Creative Commons: change may yet come for copyright.

media commons returns!

After an autumn spent retooling, MediaCommons has returned in new and better form. Check out the blog for details. Over at the much improved In Media Res it’s sports week. Congratulations to editors Kathleen FitzPatrick and Avi Santo for a job well done.

social networking in reverse

A quick note to point out LittleSis, an “involuntary Facebook of powerful Americans,” a project of the Public Accountability Initiative funded by the Sunlight Foundation. It’s something like a networked telephone book of the rich and powerful: LittleSis aggregates publicly available information about America’s officials, both public and private. If you go to, for example, John McCain’s page, you can see information about the positions he’s served in, political fundraising committees that have raised money for him, and individuals who have given him money. Clicking on the names of any of those organizations will go to the LittleSis page about them, so one can see, for example, with whom McCain sits on the Readiness and Management Support Subcommittee. All of this information has been automatically gathered, but links to sources are given on all pages – the McCain information, for example, comes from GovTrack.us, watchdog.net, Project Vote Smart, the Congressional Biographical Directory, and FEC Disclosure Reports. Nor is it limited to politicians: one can learn that Steve Jobs was a Friend of Rahm Emanuel in 2004.

LittleSis is reminiscent of They Rule, a website from a couple of years ago that mapped out relationships between the members of corporate boards – maybe They Rule is Friendster to LittleSis’s Facebook, having taken as a lesson what’s happened on the web in the past few years with the rise of social networking. LittleSis is much more open-ended: one can spend a lot of time browsing LittleSis. There’s also a wiki component: as the information is automatically gathered, not all of it makes sense yet – Bob Packwood, for example, turns up as both “Bob Packwood” (lobbyist) and “Robert William Packwood” (former Senator). More data sources are still being added; it’s important that the sources of the data can be accounted for. It’s an interesting project, and worth tracking.

One of the developers of LittleSis is Institute alum Eddie Tejeda; though he’s moved to San Francisco, he’s currently working with us to develop and new and improved version of CommentPress, which should be coming soon.

the economics of video games

We don’t talk about games here as much as we have in the past, but this John Lanchester essay is worth a look on your way to the New Year. One paragraph stands out to me, a brief consideration of the economics of creation:

It seems clear to me that by the time my children are adults, video gaming will be a medium whose importance and cultural ubiquity are at least as great as that of film or television. Whether it will be an artistic medium of equivalent importance is less clear. One of the problems is that the new consoles are difficult and expensive to create games for: no one can create a game for the PS3 or Xbox 360 without access to significant amounts of capital. The next generation of consoles is a long way away, and this will likely be even more the case by the time they’ve grown up. As the tools of filmmaking have got cheaper, those for game making have got more expensive; this might mean that the game industry never gets to move on from the need to create blockbuster equivalents. Already the industry suffers from an excessive proliferation of sequels – always a sign that the moneymen are in charge. Games do a good job of competing with blockbusters, but it would be a pity if that was the summit of their artistic development.

The interesting thing about the Internet, for better or for worse, is that it’s generally leveled the field of cultural creation: anyone can create a blog, upload photos, put videos on YouTube. Games – in Lanchester’s admittedly limited view – seem to be marching in the other direction.

an interview with helen dewitt

Helen DeWitt is a novelist who lives in Berlin. Her first novel, The Last Samurai, was published in 2002 to not inconsiderable acclaim, though it suffered, in this country at least, from having the same title as a Tom Cruise movie and a big red Talk Miramax label across the spine. Recently she’s released Your Name Here (her second novel, co-authored with Ilya Gridneff) as a PDF which is for sale on her website. Despite not having a print release, Your Name Here garnered a review in the London Review of Books by Jenny Turner; it’s been excerpted in print in n + 1 and Oxford Poetry.

Helen DeWitt is a novelist who lives in Berlin. Her first novel, The Last Samurai, was published in 2002 to not inconsiderable acclaim, though it suffered, in this country at least, from having the same title as a Tom Cruise movie and a big red Talk Miramax label across the spine. Recently she’s released Your Name Here (her second novel, co-authored with Ilya Gridneff) as a PDF which is for sale on her website. Despite not having a print release, Your Name Here garnered a review in the London Review of Books by Jenny Turner; it’s been excerpted in print in n + 1 and Oxford Poetry.

Reading Your Name Here is an interesting experience: though it’s nearly 600 8.5” x 11” pages long, I found it surprisingly legible on the screen. I never had the impulse to print it out, which is still my default impulse when I get a long PDF. DeWitt’s book works on screen, I think, because knowledge of how we read on screen informed the language of the book: when DeWitt uses emails in her book, for example, the language is exactly the same as the emails in your inbox: not cleaned-up literary language, nor forced use of slang. There are the misspellings, arbitrary capitalization, and transliterations by text encodings that have become a sort of demotic style of the present. Your Name Here is a book that feels profoundly of-the-moment: it documents how we read online in the early years of the twenty-first century. Bertrand Russell praised Stefan Themerson’s novel Bayamus as being “nearly as mad as the world,” which feels entirely apropos to Your Name Here, nearly as mad as the Internet.

DeWitt keeps a blog called Paperpools, where she posts frequently on an entertainingly vast variety of subjects. After reading Your Name Here, I sent her an email asking if she’d be willing to be interviewed about her writing and the sort of issues that interest if:book: she graciously agreed. Since she’s in Berlin and I’m in New York, this interview was conducted over email; it’s long, but I think it’s a worthwhile read. I’ve italicized my questions to set them off, but we start with Helen’s words.

Dear Dan

These are interesting questions, but crazymaking. I’ve put five attempts at a reply in the Drafts folder. Poor crazy head.

So. Take 6. From the top. My idea this time is to set this first in historical context, and then answer specific questions referring back as appropriate.

1. Writers’ bodies are contemporaneous, obviously, with those of other humans (among them writers) animate within the same brief band of time. So writers have sex, for instance, with sexual partners 100% of whom are drawn from a pool born within a century of the writer’s own date of birth – and in most cases it’s more like 50 years, or even 25.

2. The writer’s intellectual formation, on the other hand, draws on textual relations with humans who may have lived any time in the last several millennia. Fitzgerald and Hemingway were contemporaries of my grandparents, Pound, Eliot, Joyce, Beckett, Woolf were contemporaries of (hm) well, of the grandmother who eloped at the age of 16 – and family members just a couple of generations back feel very distant. But I can have an intellectual descent from Homer as direct as that of Pound or Joyce.

3. It’s not simply that temporal distance is contracted by texts. I can be influenced as an artist by all kinds of people I have very little chance of meeting – Kurosawa’s death has no relevance to his influence on my work, the fact that Scorsese and Mel Brooks are still on the planet has equally little relevance. As a writer you pick your company, and you can go anywhere you want. The limits are your willingness to grapple with other languages, your willingness to engage with other art forms. Intellectual promiscuity is at the heart of whatever it is that you do.

4. This is fundamentally at odds not only with the way texts get published and so reach the public, but also with the way these texts are ‘improved’ to what is seen as legitimacy.

5. I went to Oxford in 1979 to study classics and philosophy; I wanted the kind of formation that lunatic Pound had had, I also wanted to be able to tell a good argument from bad. So I spent an unconscionable amount of time reading the whole of Homer in Greek, the whole of Virgil in Latin (among many others); I decided at one point that I could not know anything about Greek tragedy unless I had read all extant texts, so I read the whole of Greek tragedy one summer. I didn’t have much money; I didn’t have much of a social life.

The editor who would ultimately publish my first book, Jonathan Burnham, was an Oxford contemporary whom I never met. Unsurprisingly. He was notionally studying French and Italian literature; in his first two years he did no work. He came out; he had an exciting social life in which he ran around with a lot of rich people; he was finally sent down for doing no work. We weren’t the kind of people who would meet. Another editor who wanted to publish the book went to Somerville and left after one week: she heard someone crying down the corridor over an essay on the weekend, and decided she didn’t want to be in a place where people were that obsessed with work. We weren’t the kind of people who would meet.

An agent saw a couple of chapters of The Seventh Samurai in 1996; she didn’t send it to JB, and I didn’t know to suggest this because this was someone I didn’t know. So the book reached him 20 years after we might have met if I’d been a workshy socialite. That was 2 years after I’d stopped working on the book, having been told no one would publish it; I was working on other books, all killed stone dead because Samurai suddenly had an offer of publication and had to be seen into print.

6. The person with whom I’ve discussed my work most is my ex-husband David S. Levene, also a former Oxford classicist/philosopher. DSL introduced me to all kinds of things that have turned out to be extraordinarily important (not just for projects that have been published): to bridge, to Sergio Leone, to Kurosawa, to Mel Brooks’ The Producers, to poker, to statistics, to Orhan Pamuk. DSL read Samurai in January 1997 at a single sitting and thought it was wonderful; he read Lightning Rods (Mel Brooksian satire) in 1999 at a single sitting and thought it was wonderful; he read Your Name Here in autumn 2006 at a single sitting and thought it was wonderful. If DSL were my publisher, as Leonard was Virginia Woolf’s, all these books would have been published immediately upon completion. Instead years are swallowed up trawling around the publishing industry, derailing countless other books, going crazy.

7. Jonathan Burnham saw Lightning Rods in 1999, when it had just been finished, and didn’t want it. His offer for Samurai gave him an option on another book; he did not want to give up his right to LR (despite the earlier pass), so it could not be sent to other publishers. In 2001 he decided he wanted it after all, but the deal fell apart; in 2003 he acquired it as part of a larger deal, in 2004 he decided he didn’t want it after all. Rights have recently reverted; if it ever gets published, it will happen 10 years (minimum) after the book was finished. YNH existed as a complete manuscript by the end of 2006; there’s no way of knowing whether it will ever be published.

8. JB had never seen Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai when he offered to publish The Seventh Samurai (now The Last Samurai). Somewhat unsurprisingly, his editorial comments had little of value compared to those of David Levene, who had introduced the author to the film in the first place. Needless to say, this did not mean that he did not feel entitled to hold up the author’s work on other books for 2 months waiting for these comments.

9. Zadie Smith offered last year to read YNH and put me in touch with editors who were fans of my work; “almost everyone is, you know.” Smith disliked YNH and could not be persuaded to share the names of editors who had liked The Last Samurai. An agent recently said that people in the American publishing industry speak of the book as the sort of thing that makes publishing worthwhile; he too stopped short of saying who these people were. So none of my unpublished work can be shown to these editors; knowing who they are is itself contingent on knowing the right people.

10. So we really have no chance of being contemporaries of our own contemporaries, even if we want to – if we stick with the conventional publishing model. Books I wrote or started last year, five years ago, 10 years ago, might get into the public domain in 2012, 2022, or never. The determining factor is not the quality of the books; it’s the extent to which Helen DeWitt can marshal the social skills, the obstinacy, the willingness to suspend writing indefinitely to wheel and deal, to get the fuckers into print.

11. Let’s not go into 11.

Big and dumb and obvious: do you see Your Name Here as being finished?

I don’t see it as unfinished.

As it stands, YNH works on its own terms. But there are other substantially different versions of YNH that also work on their own terms. Substantial changes were made at various points to try to respond to difficulties experienced by readers; in reverse chronological order, images were introduced to clarify structure and themes; many more chapters of Lotteryland were included; second-person narrators were included to make clear that Lotteryland was a book-within-a-book; Rachel’s early Oxford story was moved from a straightforward chronological position to flashbacks, allowing the Rachel-Ilya story to begin in medias res. Since all these changes seem to have made the book more difficult, the current version might not be best to publish.

Time already seems encoded in this book more than is usual – there are an inordinate number of dates, some of which are from this year; there’s a long sequence of correspondence from 2005 to 2006 which made me feel like I’d just missed something. The PDF that I downloaded is the version where many of the images have been removed for copyright reasons; instead of images, there are URLs where the images can be seen. Of course I plugged the URLs into my browser and immediately discovered that some of the URLs have broken, which is what happens on the web. A new version is called for; the notice pointing out that the images have been removed speaks of my PDF’s provisionality. It’s not hard to fix broken links, of course, and I assume that if your book appeared in print, you would probably be forced to make some revisions; a publisher would invariably suggest that two-colored printing is too expensive, etc.

This is what comes of not having Everything is Illuminated as one’s first book.

But one of the interesting things about working outside of the technological and economic structures of print publishing, something I find myself coming back to from time to time, is that books don’t necessarily need to bend to the old rules – if making a new edition of a book is as easy as generating a new PDF from Mellel [an Arabic word processor for Mac OS X used to produce the book], it’s not hard to imagine endlessly revising the same book. Where does it stop for you? Do you just abandon the book after a certain time?

My own feeling is that this gets ass-backwards the revolutionary opportunity offered by the Internet.

When you work on a book the final product is often nothing like what you set out to write. You see it coming. You can stop working on the book and start something new that is full of potential, or you can grit your teeth and soldier on till you’ve got a text that works on its own terms. You loathe the book with every fibre of your being, but you force yourself to cross the finish line. Then you turn to something you’re actually excited about.

The machinery of the publishing industry means that there’s a very long gap between the point where the author crossed the finish line, moved on to other books, and starting working on something new and exciting, and the point where the book is acquired by an editor and starts the long journey into print. So if you publish a book you have to go back and eat your own vomit. Then the physical object is available for sale, you’re expected to give interviews and go out and tell everyone how nice it tastes. Which means the book(s) you’re actually excited about are ripped out of your head; you go back to the fragments on paper, and you see that this looked like a great book, but the person who could have finished it no longer exists, so you feel pretty sick.

Publishing online is more like taking a book to Kinko’s. If I take a MS to Kinko’s to copy, I don’t need to know anything about the intellectual strengths of the repro op: the copy will have only the mistakes that were there when I walked in. That’s not to say it won’t have any mistakes – but there’s no way in the world that hundreds of alterations will creep into the text behind my back. So I can copy it and give it to friends and forget about it; this doesn’t get in the way of thinking about other books. There’s absolutely no reason why the occasional trip to Kinko’s should stop me from writing 10 books a year.

The difference becomes really obvious when you have a book that’s technically difficult. Suppose I’ve written a book in Mellel, which is good for Arabic. The designer and typesetter are unlikely to have Mellel. The text will have to be imported to Quark or InDesign. Could I typeset the book myself to ensure that it’s done by someone who can tell whether the text is right or wrong? In your dreams. Could I at least deal directly with the technical people, could we actually meet, so we can sort out possible problems? The fact that an editor has never heard of Quark, the fact that he stammers and turns pale if asked for a screenshot, does not mean that he will not want all discussions of the text to go through him. So the thought of just saving a document straight to PDF and disseminating it in that form is unbelievably seductive.

There’s an incontrovertible reason for going back to a book you finished years ago, to putting books you’re excited about on hold, to spending months defending a text from mad copy-editors and linguistically challenged typesetters: money. If you get an advance, that might buy time one day to concentrate on other books without interruption. (If you’re unlucky, of course, you’ll go insane, so the money won’t help.)

So I would have thought you made a trade-off, publishing online: you don’t get much in the way of money, but the text is in the public domain without destroying all your other work. If you go on endlessly revising, it seems to me you’ve thrown away the best reason for publishing online in the first place.

I’m curious about how your blog, Paperpools, might have functioned as part of the book-writing process.

What happened was this: I had sent YNH to Warren Frazier, who represents Mark Danielewski, in early 2007, and he claimed to be very enthusiastic about it but to need time to reread it to see how best to present it to publishers. He said we would discuss it ‘by the middle of next week at the latest’, which to me means ‘no later than next Wednesday’. He then kept postponing the discussion at the last minute, needing another week, for four weeks in a row. I was going insane, because this was time I could have spent on my Guggenheim project. We had long inconclusive phone conversations, after each of which I would send off a long detailed explanation of the artistic universe of the book. Nothing helped. From time to time he would say he wished he knew me. I don’t know that I thought a blog would help this or any other agent to know me, but at least it would be a forum where it would be possible to talk about ways of looking at texts that made sense to me.

If you’ve read the blog Language Log, you’ll have seen that they have many posts on the misconceptions governing much copy-editorial practice. The fact that the LL discussion is in the public domain offers writers the chance to justify their practice by appeal to an authority – something that counts for a lot with both editors and copy-editors. It seemed possible that having a discussion in the public domain of the kinds of things a text could be might also be helpful, if not for me then for other writers.

And a more general question leading from that: how does blog-writing & the feedback loop inherent in it affect you & your work?

In good ways and bad ways. One good way is that if one comes across something that is absolutely amazing one has a way of showing it to people without having to ‘motivate’ it in a work of fiction.

Another: one can write with the freshness of new enthusiasm – and publish without delay. It’s depressing, yes, to get excited about something and then have a succession of industry insiders pull long faces and say no one will be interested. But if people like the idea it just means you can spend a year or so putting a book together, at the end of which you do a roadshow in which you try to simulate enthusiasm you actually felt once upon a time when the world was new. Those with personal experience of erections will probably understand the appeal of instant gratification.

Another: because most readers don’t read a blog at a single sitting, there’s no oppressive sense of length – the blog may be thousands of pages long, but it doesn’t feel that way to the reader.

Another (finally): it reminds one of how little anyone really knows about what will catch readers’ interest. One sometimes spends hours on a post which one considers to be profoundly original and important, expecting frenzied discussion to break out – only to find no one is interested. At other times one tosses out a post one had thought hardly worth publishing, and this turns out to be startlingly popular and get thousands of hits. And that, of course, happens partly because some other blogger with a large following – one other person – happened to like the post. (It’s pure chance.) And one realises something extraordinary – writing this little blog one actually has more feedback, more immediate feedback, than a publisher has any chance of. So it’s easier, a bit easier to deal with the vicissitudes of publication.

I said finally, but actually the thing that’s absolutely wonderful is that you have direct access to the judgment of your peers. There are some fabulous blogs, some with big followings, some relatively unknown; if a blog you like mentions your blog favourably you’re walking on air. Reviews of a book don’t begin to compare. A book review is commissioned by a periodical, sometimes with some string-pulling behind the scenes; the chances that the person who writes it is on your personal list of top 10 writers are slim to nil. If you follow blogs, there are people you check every single day; I love Language Log, I love Languagehat, I love Bremer Sprachblog, I loved the old Freakonomics, and when someone you follow faithfully quotes you, or tells readers you have a great blog, it’s . . .

what? Well, it’s not just that it’s a thrill; it feels very pure, because bloggers work on a purely voluntary basis. People get sent books to review for all kinds of reasons, which may have little to do with inclination or qualification. It’s a meritocracy in a way that the world of published books is not: Anatol Stefanowitsch is consistently witty and well-informed, Steve Dodson of Languagehat has an extraordinary combination of literary sensibility and linguistic acuteness, the contributors of LL probably need no introduction to an online audience, and most of what they write could never see the light of day in mainstream print publications. So if you get a favourable comment you feel uncomplicatedly happy.

Oh, and finally finally finally – it gives you the chance to point readers in the direction of specialists they might never otherwise think of reading. I feel very lucky in having e-mail correspondence with Rafe Donahue, the biostatistician (witty, well-informed, and scarily adept with R) – and a blog offers the chance to let readers in on the secret.

What’s bad? Weeeeeellllllllllllll – if you leave the blog open to comments you’ll get comments. If you get too many daft comments you start self-censoring. If you’re a writer, you know that the energy of a book comes from faith in the intelligence of the reader. So you may find you need to do original work offline and not say anything about it, you may need to be a bit protective.

A post on Paperpools, Rashomon & Robocop points to an emphasis on process rather than the finished product. Does the same sort of feedback loop happen with the book being available online – do other people buy it, read it, and then pester you with questions? Is this back & forth useful to you as a writer?

People haven’t written to me with many questions or comments. Mithridates had some clever things to say.

Your Name Here has an overt fascination with languages, not least Arabic. I remember very little from my year of Arabic in college – just enough that I could sound out your transliterations without too much trouble – in no small part because I was tripped up by the distinction between written and spoken Arabic, which is tremendously different from the way that relationship works in English or the romance languages. Reading Arabic is no guarantee of being able to speak it comprehensibly, as Lebanese Arabic sounds completely different to Yemeni Arabic, for example. There’s a parallel, maybe, to Walter Ong’s ideas about orality and literacy – he points out, quite sensibly, that oral language and literate language are two entirely different things.

I’ve always loved Queneau, who of course not only had much to say about this but wrote some brilliant books playing the two off against each other.

His idea about secondary orality has seemed more & more prescient over the past few years – there’s been no shortage of people grumbling about how the kids write on YouTube or MySpace has little relation to the tradition of literate English beyond being in the same script. One of the things that was most striking to me about Your Name Here is how that’s become a part of the book’s English: the misspellings and random capitalization, fragmented sentences, punctuation being lost to messed-up text encodings.

I loved those e-mails that came from alien keyboards, bearing the marks of the place and time of composition.

It’s part of the book’s verisimilitude. Your Name Here feels right to me as a reader in that it does capture the way we read from the screen now; I think this is why it feels right to read it as a PDF on screen, even if the PDF hasn’t been specifically designed for screen reading. I can imagine that it would work printed out on 8.5” x 11” paper & read that way. I’m not sure that it would feel quite the same were it an actual print book – putting screen language in print form seems retrograde, like making a calligraphed edition of Ulysses on papyrus, cute but somehow beside the point. Should it?

I’m not sure: the codex was originally copied out by hand just as scrolls had been, but it offered a more convenient way to read a text. Then there was a period when there was a gap between the technology of texts produced by those who wrote them (whether privately or professionally) and that of those who published. Now we’re back in a situation where writers and publishers have access to pretty much the same technology, as far as the text on the page goes, but a publisher can still offer the simplicity of double-sided printing, of text that the eye can take in at a glance.

A problem for YNH may be, though, that our perception of length when reading onscreen is quite different from that reading pages of a book. An e-mail can go on for a couple of thousand words and not feel long; one sees it printed out and is quietly appalled.

We’re in an odd time in the history of literacy – Sven Birkerts very adroitly brought up Gramsci’s line about “the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear” in the mid-90s, which still seems very apt. Where do you feel like you stand, relative to print?

I’ll try to answer this first in relation to YNH, then more generally.

When Ilya and I were working on YNH, one thing that interested me was the way that a text is the result of all sorts of discussions and constraints that normally aren’t visible. Every single published book is governed by a contract, a text readers don’t see, and it is generally the result of an enormous amount of scurrying around behind the scenes. So I thought: how can we possibly assess the texts we see when we don’t know the contractual restraints on the author? when we don’t know whether the publisher was willing to respect the contract? when we don’t know whether the author had a powerful agent or a weak one, whether the published book was substantially what the author wanted or the result of a lot of arm-twisting off-stage? Editorial comments are never made public; why not?

So I thought, not that all this material should be included in a book, but that it would be interesting if all the background correspondence and the contracts and so on where available on a CD. For that matter, why not include earlier versions of the book, or at least significant earlier versions?

I like books, actual printed books, a lot. It seems to me, though, that the culture which produces the ones we see has some misplaced anxieties. We live in a culture where standards of ‘correctness’ and consistency are applied to the printed word, so that ‘properly’ published books are expected to eliminate the traces of composition. A text is not supposed to bear the marks of the circumstances of its writing. That seems to me to be an unnecessary concern – but you don’t really need the Internet to stop fretting about it.

There are some things you can do more easily if you can draw on the resources of Hypertext. You can write a text in several languages unselfconsciously, or maybe I mean, without obtrusive consciousness of the reader. You can just have a couple of characters speaking Spanish, or Arabic, or Japanese, and readers who can read the languages can read the text, but those who can’t can click through to a translation. So you can make use of the textures of those different languages without giving the primary text a lot of extra baggage – and still make it comprehensible to readers who need more in the way of explanation. This isn’t especially relevant to YNH, but it’s the sort of thing I think could more easily be done online or in an e-book than in print-on-paper. I came across a wonderful website a while back with graphics which enabled you to drill down on results of Grand Prix racers, if one did this in a work of fiction online one could have something very stylish whereas if one tried to do it in a book it would feel not just long but cumbersome and messy.

Can we actually talk about that last question sensibly if we’re ignoring economics? A mountain of letters have been spent imagining electronic literature existing in some sort of economic tabula rasa that exists only in the minds of academics & libertarians. A good chunk of Your Name Here is about efforts for novelists and journalists to get paid, a concern echoed in The Last Samurai and the Paperpools posts about it. It’s no surprise that the majority of writers are presently ill-served by publishers. Does what you’re doing with Your Name Here feel like a way forward? How else might one proceed?

I have to say that I didn’t see selling a few copies online as a rejection of the normal method of publication; readers were badgering me to see copies of the book, and I had no idea when it would get published, so it seemed sensible to sell it to those who wanted it.

I think what I’d like is to see is something completely different. Something tells me I’m about to sound very, very crass, but here are the two points that strike me as absolutely crucial if we want to talk about that clinking clanking sound:

1. Aura and the market.

Walter Benjamin suggested that in an age of technological reproducibility the aura of the artist was lost. This looks wildly implausible if we look at the development of the modern art market: auction prices in the art world, one’s inclined to say, depend crudely on the possibility of the scarcity of certain works. In that world, there’s an obvious difference in value between a painting certified as from the hand of Uccello, a painting di bottega, a painting of doubtful provenance and so on. But it’s not as simple as contact with the artist’s hand – Hirst, Koons and others show aura persisting in the absence of execution. (What’s important is what? An object in direct line with execution of the artist’s will?)

The way we currently permit value to inhere in books throws this source of startling levels of revenue out the window. A published book, an object which makes multiple copies available at modest price to a large audience, doesn’t elevate the original to the position of singular object of value – our convention is that the processes of publication manufacture legitimacy for the replicas at the expense of the original. Di bottega is better than autograph, spam is better than ham. So when a book is published (replicated) we don’t have an exhibition at which the original, sketches, print-outs with author’s mark-ups, the laptop with all the various versions are on display and available for sale and capable of appreciation in the resale market – we have a devalued set of ‘drafts’ and the real thing. A real thing which, sadly, typically drops to a resale value of a few cents upon purchase.

This financial structure not only deprives writers of money they might otherwise earn as a matter of course from sale of original material – it also eats into the time they have to write other work. A painter is not expected to hand in a painting and then set aside a year or so to a) changing it in light of comments from the gallerist and b) waiting for the gallerist’s staff to touch it up before deciding whether all the alterations can be allowed to stand. (The painting is not thought deficient in value if untouched-up by the gallerist, the receptionist, the gallerist’s girlfriend.) A painter can paint. Do we think that any painter, regardless of ability, is automatically superior to any writer? I don’t think so, but we have a system of production that presupposes that position, and the result is one with crippling financial consequences for writers.

So, long story short, there is money to be made and no one’s making it, and this could be fixed.

2. Fundraising

I worked for about a year as fundraiser for an NGO that supported women’s projects in what we called the developing world.

Fundraisers go after money in various ways: grant applications to governments, NGOs and other institutions; development of major donors (businesses, wealthy individuals); mailshots (collect donations of varying sizes from individuals, expand the donorbase); events; management of volunteers. Each of these exercises involves different skills, and a big NGO might well have fundraising specialists for the different methods.

Generally speaking, going after donations from large numbers of individuals is expensive and time-consuming. Mailshots are worth the bother because you get information about the donors with the donation, which means you can focus future mailshots on those who were willing to donate in the past. Events are worth the bother partly because they offer a chance to cultivate individuals who may make substantial gifts somewhere down the line.

Suppose we now look at the book business. How does that work as a way of getting money for writers so they can write? Well, the way it works is, you try to sell a very large number of physical objects, collecting a dollar or two off each one for the author – from people you never contact again.

I once knew a senior partner in a Wall Street firm who loved Susan Sontag’s The Volcano Lover. He talked at length about the wonderfulness of this book, the character of the Collector, the general brilliance. He was making $1 million or so a year. Of which Andrew Wylie, Sontag’s agent, had cleverly managed to garner a couple of bucks for Sontag. There was no structure in place to encourage this ardent fan to, say, sponsor Sontag’s travel expenses, offer Sontag six months’ writing time at his vacation home in Maine, buy Sontag a new car, who knows.

This is deeply baffling. One of the problems for a fundraiser is that it’s hard to raise undedicated funds. Good fundraising copy often focuses on an individual; you excite the donor’s sympathy for Precious, who walks 10km twice a day to go to school, and then the donors all want to buy books, school uniform and a bicycle for Precious. If you’re not careful with the wording you could find yourself under a legal obligation to send half the take from the appeal to Precious. And you hauled in all this money and goodwill for someone donors had never heard of before, with a single page of copy. It takes five minutes to read, and you’re sweating blood to draft something that will get people to spend the five minutes. Whereas.

When people read a book they typically spend a minimum of a couple of hours on it. Sometimes they read it at a single sitting; sometimes they live with it for weeks. Sometimes they forget it – but sometimes it stays in the mind for years, sometimes it saves the reader from suicide, sometimes it changes the reader’s life. So it has the power to make a much stronger connection with the reader than a little read-and-toss mailshot – but the strength of this connection does not translate into extra time for the writer to write.

Writers spend a lot of time getting in each other’s way. There are a few places that offer residencies – normally, disruptively, places that have a lot of other writers and artists also in residence. But there are plenty of readers like my Wall Street lawyer, people with second and third homes they never have time to visit – and even the most highpowered agents never think of encouraging those readers to give the freedom of silence to writers they admire. Agents go after big advances – which means a writer does a roadshow to buy silence somewhere down the line. It’s done this way because this is the way it’s done. It doesn’t have to be done this way; if it were done a different way, writers would write better books in less time.

So, to revert to the role of the Internet in all this: the Internet has the power to reduce the amount of time writers have to trade for legitimacy. It has the power to change readers’ relationship to writers. If a book (or a blog, or a web comic) changed your life, why not buy its author a bicycle? Or a goat? Or a bottle of wine? Why not offer its author six off-season months in your summer cottage on the Cape?

Those look to me to be likelier ways forward than for writers to pay the rent by selling PDFs online.

Or maybe: in a post called Being Ilya Gridneff you talk about the Internet’s “strange fetishism of writing as commodity”; how do you square this with making a living?

I don’t have Internet access in this café so I can’t check this quote. It strikes me as silly to draw a distinction between wonderful prose in ‘informal’ forms such as e-mails, forms which are currently not classed as commodities and so can’t be sold, and other forms which currently happen to be classed as commodities. Most modern readers pay much more attention to Shakespeare’s plays than to The Rape of Lucrece and Venus and Adonis; the plays only got published because friends of Shakespeare’s thought it worth the trouble to see them into print. The Internet ought to make us more aware of the extraordinary resources of language and images, many of which don’t slot well into what publishers see as publishable. It’s silly to blame publishers for dealing with the market as they see it; we should look for other ways of ensuring that people capable of wonderful writing have time for it.

How do you function as part of the book? I ordered Your Name Here from your website, and fter sending some money through Paypal, I received an email from you telling me where to download a copy of the book. Soon after starting to read the book, I was surprised to discover that same email address as a recurring element in the text. It’s one thing to have a character with the same name as the author moving through a work of fiction – it’s an old trick by now & we as readers are mostly used to that. But something about this struck me as more of an insertion of the author into the project. As a reader in the age of the fictitious memoir, one needs to be cautious about this sort of thing – Coetzee, for example, has been messing with over-hasty book reviewers for his past few books. The reader of Your Name Here naturally turns to your blog & starts to wonder where Helen DeWitt in Your Name Here ends and the Helen DeWitt who blogs at Paperpools begins: the book dares the reader to do so.

Roland Barthes says “Je” ne peux parler de “moi” – there is an individual, of course, who makes use of the first-person pronoun, but not necessarily one in a privileged position to pronounce on where this line should be drawn.

The Helen DeWitt of the book and the Helen DeWitt of the blog are both linked to texts that are available to my family. Both are subject to extensive censorship; the things that are left out are pretty much the same in both cases. So the distinction between public and private, to anticipate your next question, isn’t very helpful – they’re both public.

I should have checked with Ilya to see whether he wanted a real e-mail address published. Two of the other authors of e-mails specifically asked to have real e-mail addresses in the text.

Obviously notions of what is public and private are being rewritten for everyone right now – how are they being rewritten for the author?

I know there are writers who attach great importance to something they see as a private sphere. That doesn’t have much meaning for me.

A few years ago I attempted suicide. I sent an e-mail with instructions for dealing with the body to the lawyer who was responsible for the problems I faced. I was surprised to discover later that she had sent this on to a friend, who had sent it to my landlady, who had sent it to the police, who had sent it to the press. It got a lot of hits on Google.

I’m afraid my first thought on discovering this was that it was a fabulous piece of luck. It was the sort of thing that journalists like; if I could give some interviews it could double or triple the sales of The Last Samurai. The book’s publicist had told me, upon its launch, that no one wanted to interview me; now everyone wanted to interview me. But the reason my publishers had given me the runaround, the reason they treated my contract as a joke, was that the sales of the book had not been spectacular enough to make them anxious to please. If the book were to sell another 100,000 copies not only would my existing publishers change their tune, every other publisher in the business would be happy to talk to me.

I can’t say that this struck me as particularly outré, but it’s a position that hasn’t found much favour with people I’ve talked to. I went to talk to Jim Rutman, an agent with Sterling Lord; I asked whether it would be possible to write for Harper’s, the New Yorker, whether he could set up a press conference. Rutman (appalled): But that means throwing yourself in the media maelstrom. This summer I talked to another agent, Markus Hoffmann, who was interested in representing me and claimed to admire YNH. I mentioned that one of the useful things about having an agent was having someone who could organise a press conference if one had a highly-publicised suicide attempt. Hoffmann: If a client attempted suicide I would certainly not be thinking about a press conference, and if the client asked me to do this that would be the very reason not to do it. There is more to life than books and sales. (You’ve read YNH; I trust you find this as peculiar as I do.)

To revert to some very early comments, most of the relationships that matter to me are with dead writers. If I could have sold off a suicide attempt I would have had more time for reading Spinoza. I don’t think the Internet has any connection with this, though, and I don’t think I am in a position to speculate on the changing boundaries between public and private for other writers.

A question that follows is one of about the scale of this project. I assume that this right now this is a small-scale project, at least small enough that you can afford to still attach your email address to emails to those purchasing the book. (p. 274: “Unlike the other characters, you’re not only getting paid, you have direct access to the author. You can change the course of the book.”) How sustainable is this? I’d guess that it’s fine if 100 people have your email address and feel, as I did, free to bother you; it becomes less fine if 1000 or 10,000 people have your email address and feel free to bother you. It’s nice to hear from your audience, but at a certain point, does the audience become troublesome?

Well, for a while I was following up all the notifications of payment with an e-mail because the Buy Now button I had constructed over at PayPal seemed to be working erratically – people were not always getting put through to the download page. That was a nuisance, not because of the numbers involved, but because I felt I must always be contactable in case things went wrong. So I asked Mithridates if I could make him the designated troubleshooter, and people can now pester him if they haven’t managed to get a PDF.

I’m not sure that numbers are what make dealing with the public unmanageable. It sometimes happens that one gets drawn into a correspondence with a single reader and that this takes up a lot of time and energy. If the reader is, what’s a good term for this, a private individual (sounds comical but let’s leave it), it’s not too bad; but sometimes the reader is someone with a public presence, a hotshot. That’s awkward, because that sort of person has connections with people in the industry who are keen to foster connections with a hotshot.

And legal concerns start wandering in: at a certain point, I imagine that the Microsoft lawyers might start wondering about the ads for MSN Messenger embedded in the text and whether they should do anything about that.

I think I assumed they would be happy to have the ads reach a wider audience, though yes, I suppose one should check.

To your mind, where does an editor come in?

This is where the (I now see) horribly long preamble pays off. The Last Samurai only came about in the first place because a close personal friend introduced me to Kurosawa. DSL is now Professor of Latin at NYU. He loves Moby Dick, Faulkner, All the King’s Men, Cormac McCarthy; loves Wagner, Richard Strauss, Schoenberg; has an extensive knowledge of cinema; introduced me to bridge and poker and came up with the idea of a book showing the way mathematicians think about chance. Introduced me to Mel Brooks’ The Producers.

DSL is not a DeWitt alter ego; through him I come to work I wouldn’t otherwise have considered. If he comments on a book, I can put his comments in context; I know the writers I love that he doesn’t care for, I know the kind of thing he likes in a work of art. I also know that this is someone with an extremely powerful mind whose views carry weight.

DSL has a photographic memory and a meticulous eye for detail; I could call DSL up while revising Samurai and say: David, you remember that comma on page 283? I’m wondering whether this is really a good idea. And he’d remember the comma on page 283.

No editor can compete with DSL on his own ground. If DSL introduces me to Kurosawa, of whose work he has a photographic memory, it would be ludicrous to expect an editor with no knowledge of the films to have something useful to offer.

Is this to say that there is no point to having an editor? Surely this is simply to say that DSL is what an editor should be: someone with strong tastes which do NOT simply replicate mine. Someone with profound knowledge of material relevant to the book under consideration. DSL started out with an advantage on books written so far, for the entirely unsurprising fact that an intelligent reader with whom one has intellectual rapport will come up with suggestions that prove fruitful – whose results he is then in a privileged position to judge.

In other words, it would be perfectly possible to have an equally fruitful relationship with an editor in the publishing industry. But that would require something that agents strenuously resist, namely giving the writer a great deal of information about editors’ intellectual strengths early on, giving the writer a chance to talk to editors early on, so that an editor’s intellectual strengths were of some use to the book.

[At this point, obviously, I’m talking about the role of editor as someone who strengthens the book, rather than as someone who selects it for publication.]

A book like Your Name Here would present tremendous demands on a copy editor. (Example, more or less at random: is the Arabic on p. 147 tracked-out so the reader can distinguish between the characters or did something go wrong in Mellel?) On Paperpools, you’ve diligently documented the role of the editor and copy editor on The Last Samurai, which can’t have been an easy book for an editor to deal with, though it seems like a piece of cake next to the glorious mess of Your Name Here.

Well, it’s good to have someone catch factual mistakes. I’m not sure the problem is precisely that one can’t copyedit the real world: within a book you have different voices. It might be best to leave Ilya’s e-mails untouched, as the best way of keeping that voice true to itself, but one might want to look at some of the other voices and think about the texture that would work best. I agree, the Chicago Manual of Style would not be of much help here.

But most writers need editors: speaking as a reader, I trusted you enough to read The Last Samurai because your work had already been vetted by other editors, which is how most readers function. One feels that something should exist between the old editorial apparatus and a new world where everyone is an editor, but what?

I think you’re conflating two editorial roles. A professional editor rejects most of the MSS he sees; the reader of a published book can take it that someone whose opinion is worth respecting has selected it for publication. The other thing an editor can do is improve a MS with useful suggestions. Let’s look at this another way.

If we look at the contemporary art world, it’s strongly influenced by a few gallerists, a few collectors, many of whom have highly idiosyncratic tastes. Many years ago Charles Saatchi bought out Jenny Saville’s degree show and gave her £20,000 to paint for a year. (I think he took out some kind of option on the paintings, but I don’t remember the details all that well.)

Collectors don’t choose work in the hope that 20,000 or 100,000 or 1,000,000 million other people will like it; they spend serious money on work that they themselves like.

To some extent editors used to be in that position. An editor would see a book that s/he thought was brilliant and decide to publish it, and it was then the job of the sales force to get it sold. We hear that this has now changed; that the sales and marketing people tell editors what they are permitted to acquire.