from the nouveau roman . . .

I’ve been working out of the Brooklyn Public Library lately, which has free wireless internet and an interesting collection of books. The organizing principle seems to be, as far as I can tell, that everything remotely interesting gets stolen. This means, in practice, that they have an exceptional collection of criticism of the French nouveau roman, which seems to have gathered dust on the shelves there since the early 1960s. The nouveaux romanciers were a loosely-knit group of novelists from the 1960s determined to shake the French novel out of existential doldrums through the use of new styles of narrative. Nathalie Sarraute and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s microscopic examinations of everyday life might be seen as exemplary of the movement, though the novels of Marguerite Duras are probably the most widely read today.

To me, the most interesting of them is Michel Butor, who wrote four increasingly experimental novels in the early 1960s, and then tired of writing novels altogether. Mobile, his next major production, confused the critics immensely, some of whom declared that not only was it not a novel, it wasn’t a book at all. Mobile is fantastic: it’s a travel guide to the United States presented as a collage, abandoning the author’s voice for bits of history, advertising, and found text. Following the example of Stéphane Mallarmé, the texts are spread over the pages, an analogue to the spatial journey the book describes, presenting a range of sensory (and historical) impressions of America. The French version has the text rotated 90 degrees so you have to hold the book sideways, a feature sadly not carried over into Richard Howard’s otherwise wonderful English translation (recently republished by the Dalkey Archive). While the author’s voice seems to be absent in favor of his found materials, there’s clearly a subtext: the history of racism underlying the country from it’s deep history to the present Butor found in 1964. More than a book, the effect on the reader is like that of the film-essays of Chris Marker (I’m thinking particularly of A Grin without a Cat) and Agnes Varda.

To me, the most interesting of them is Michel Butor, who wrote four increasingly experimental novels in the early 1960s, and then tired of writing novels altogether. Mobile, his next major production, confused the critics immensely, some of whom declared that not only was it not a novel, it wasn’t a book at all. Mobile is fantastic: it’s a travel guide to the United States presented as a collage, abandoning the author’s voice for bits of history, advertising, and found text. Following the example of Stéphane Mallarmé, the texts are spread over the pages, an analogue to the spatial journey the book describes, presenting a range of sensory (and historical) impressions of America. The French version has the text rotated 90 degrees so you have to hold the book sideways, a feature sadly not carried over into Richard Howard’s otherwise wonderful English translation (recently republished by the Dalkey Archive). While the author’s voice seems to be absent in favor of his found materials, there’s clearly a subtext: the history of racism underlying the country from it’s deep history to the present Butor found in 1964. More than a book, the effect on the reader is like that of the film-essays of Chris Marker (I’m thinking particularly of A Grin without a Cat) and Agnes Varda.

Butor continued to experiment with forms: he made radioplays for simultaneous voices, and has worked in collaboration with just about any sort of artist that can be imagined. Though he’s produced an enormous amount of work since the 1960s, only a tiny fraction of it has been independent work. One of the first of his collaborations was with the composer Henry Pousseur; in the late 1960s, the two of them wrote an opera called Votre Faust, “your Faust”. It was a modern retelling of the Faust story, but with a twist: at certain points during the production, the audience was asked to vote on what should happen next. Depending on how the audience voted (or failed to vote, which was also taken into account), the opera might have any of 25 different endings. After a long public gestation, it was finally produced in 1969 in Milan. It went over like a lead balloon, and subsequently largely vanished from sight, though the critics’ pre-performance excitement remains frozen in time at the Brooklyn Public Library. LPs were evidently put out at the time. I’m curious what exactly was on them – was it a full recording of all the possible music, letting home listeners construct their own personal opera, or did it only contain one version?

Butor is still happily alive and still churning out poetry and other works; at some point in the nineties, he had his own website, though he doesn’t look to have updated it in a while. His art, though, seems to have been perpetually ahead of his time: while Votre Faust didn’t work in a live setting, it might have made a fine CD-ROM or DVD. I don’t know if he’s ever written specifically for electronic media, as Chris Marker has; I’d love to see what he would do with it.

. . . to the nouveau romance

“Harlequin” has achieved brand ubiquity: a “harlequin” is a trashy, disposable romance novel, just like a “kleenex” is a tissue and a “xerox” is a copy. We don’t even bother thinking about the word any more than we usually think about romance novels. Do the romance novel and the Future of the Book have anything in common? Of course not! any right-thinking future-bookist would angrily declare. The future, as everybody knows, is the domain of science fiction, not the romance. A look at eharlequin.com, Harlequin’s website, suggests that this might not be the case. The first surprise: how much content they have online. The second surprise: how much is interactive, and how much is devoted to the process of writing. Look at how much there is in the writing bulletin board, dedicated to helping the users write their own romance: templates for various varieties of romances that Harlequin publishes, advice on business, suggestions for those with writer’s block.

“Harlequin” has achieved brand ubiquity: a “harlequin” is a trashy, disposable romance novel, just like a “kleenex” is a tissue and a “xerox” is a copy. We don’t even bother thinking about the word any more than we usually think about romance novels. Do the romance novel and the Future of the Book have anything in common? Of course not! any right-thinking future-bookist would angrily declare. The future, as everybody knows, is the domain of science fiction, not the romance. A look at eharlequin.com, Harlequin’s website, suggests that this might not be the case. The first surprise: how much content they have online. The second surprise: how much is interactive, and how much is devoted to the process of writing. Look at how much there is in the writing bulletin board, dedicated to helping the users write their own romance: templates for various varieties of romances that Harlequin publishes, advice on business, suggestions for those with writer’s block.

There’s also participatory authoring: in the Writing Round Robin, participants take turns writing chapters of a novel, and critiquing others’ chapters. Unlike some of the open source and wiki novels elsewhere on the web, this is highly moderated writing: note the rules here. This might be expected: Harlequin, after all, is a publishing house, and experimentation isn’t being done for experimentation’s sake, but because it fits into a business model.

There’s also participatory authoring: in the Writing Round Robin, participants take turns writing chapters of a novel, and critiquing others’ chapters. Unlike some of the open source and wiki novels elsewhere on the web, this is highly moderated writing: note the rules here. This might be expected: Harlequin, after all, is a publishing house, and experimentation isn’t being done for experimentation’s sake, but because it fits into a business model.

But to bring this back around to Butor’s opera: consider eharlequin’s Interactive Novel, where chapters are added one at a time, and the readers vote on how the work should progress: a chapter’s written (or put online) accordingly. Right now the meddling readers are worrying themselves over whether or not Tess is pregnant with Derek’s baby.

It’s become a truism that porn drives technology: see here for one of the many observations of this. (Who first made this connection? Does it date back to before the VCR?) It might not be so surprising that seems romance is doing the same thing in the popular arena of the novel. Even more surprising might be that it’s romance where this is happening. Sarah Glazer, writing in the New York Times Book Review was surprised to find that the biggest current growth market for ebooks is in romances. Is the future of the book to be found in the romance? It seems counterintuitive, but there seems to be more of a participatory literary culture at Harlequin’s website than a quick scrutiny of some scifi publishers’ websites would reveal. (I’d love to be proved wrong about this – can anyone provide examples?)

There’s almost certainly no direct line that goes from Butor and Pousseur’s Votre Faust to eharlequin.com’s Interactive Read, except, I suppose, in the head of this particular reader. There’s a whole history of interactive fiction that I’ve omitted – Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, Milorad Pavić’s Dictionary of the Khazars, a whole slew of Choose-Your-Own-Adventure books. But it’s interesting that Butor & Pousseur’s unsuccessful attempt (“It was very difficult to play. . . But we both have made many efforts to make it easy to realize. Without success.” notes Butor in an online interview) should be taken up in such an unlikely form.

The romance novel, everyone concurs, is not art. There’s not a great deal of critical theory thrown around about romances. The New Novelists were all about creating critical context for their fiction: Robbe-Grillet kicked things off with Pour un nouveau roman, a collection of essays on the novel’s past and present, and Butor wrote a piece titled “The Future of the Book”, among many others. This might be why the nouveau roman is generally considered a failure: it didn’t end up remaking the mainstream of fiction. The contrast with eharlequin might be instructive: outside of the critical eye (and with the support of publishers) romance readers are becoming authors, seemingly constructing their own possible future of the book.

Boing Boing points out that professor/prankster Kembrew McLeod has released an electronic version of his new book on copyright Freedom of Expression on his website. The electronic version is released with a Creative Commons license. McLeod’s book has not a little to do with what we’re working on at the Institute, so I quite happily downloaded the book – you can too! – and found myself with a 384-page PDF of the book. It’s indeed the whole book, almost exactly as Doubleday printed it, with the addition of a Creative Commons link on the first page. If you happen to know a book printer and some extra cash, you could send them this file and get a book back in a couple weeks. If you don’t have access to a print shop and extra cash but you do have 384 sheets of 8.5” x 11” paper & a fast laser printer, you could print it out yourself and have your own telephone-book sized stack of Freedom of Expression.

Boing Boing points out that professor/prankster Kembrew McLeod has released an electronic version of his new book on copyright Freedom of Expression on his website. The electronic version is released with a Creative Commons license. McLeod’s book has not a little to do with what we’re working on at the Institute, so I quite happily downloaded the book – you can too! – and found myself with a 384-page PDF of the book. It’s indeed the whole book, almost exactly as Doubleday printed it, with the addition of a Creative Commons link on the first page. If you happen to know a book printer and some extra cash, you could send them this file and get a book back in a couple weeks. If you don’t have access to a print shop and extra cash but you do have 384 sheets of 8.5” x 11” paper & a fast laser printer, you could print it out yourself and have your own telephone-book sized stack of Freedom of Expression. While it’s certainly poor form to complain about what’s being given away for free, it’s a remarkably painful experience to try and read this book on your computer. In large part, this is because it’s not meant to be read on a screen. This PDF is the same file that Doubleday’s production staff sent to the printer – with crop marks and the QuarkXPress filename at the top of every page. Because there’s padding around the text so that it can be safely printed, you need to blow up the magnification to actually be able to read the text. There’s a great deal of wasted space you need to page through (click on the thumbnail at right for an example of how this looked in full-screen Adobe Acrobat on my computer). Because Doubleday’s making books in Quark with no thought to reusing or repurposing content, this file doesn’t have any of the niceties that a PDF could have – an interactive table of contents, for example, is useful in a three-hundred page book. Worse: while one of the great benefits of the Creative Commons license is that it allows users to quote and create derivative works from licensed material. It’s not as simple as you’d like to copy text out of a PDF.

While it’s certainly poor form to complain about what’s being given away for free, it’s a remarkably painful experience to try and read this book on your computer. In large part, this is because it’s not meant to be read on a screen. This PDF is the same file that Doubleday’s production staff sent to the printer – with crop marks and the QuarkXPress filename at the top of every page. Because there’s padding around the text so that it can be safely printed, you need to blow up the magnification to actually be able to read the text. There’s a great deal of wasted space you need to page through (click on the thumbnail at right for an example of how this looked in full-screen Adobe Acrobat on my computer). Because Doubleday’s making books in Quark with no thought to reusing or repurposing content, this file doesn’t have any of the niceties that a PDF could have – an interactive table of contents, for example, is useful in a three-hundred page book. Worse: while one of the great benefits of the Creative Commons license is that it allows users to quote and create derivative works from licensed material. It’s not as simple as you’d like to copy text out of a PDF.

To me, the most interesting of them is Michel Butor, who wrote four increasingly experimental novels in the early 1960s, and then tired of writing novels altogether. Mobile, his next major production, confused the critics immensely, some of whom declared that not only was it not a novel, it wasn’t a book at all. Mobile is fantastic: it’s a travel guide to the United States presented as a collage, abandoning the author’s voice for bits of history, advertising, and found text. Following the example of

To me, the most interesting of them is Michel Butor, who wrote four increasingly experimental novels in the early 1960s, and then tired of writing novels altogether. Mobile, his next major production, confused the critics immensely, some of whom declared that not only was it not a novel, it wasn’t a book at all. Mobile is fantastic: it’s a travel guide to the United States presented as a collage, abandoning the author’s voice for bits of history, advertising, and found text. Following the example of  “Harlequin” has achieved brand ubiquity: a “harlequin” is a trashy, disposable romance novel, just like a “kleenex” is a tissue and a “xerox” is a copy. We don’t even bother thinking about the word any more than we usually think about romance novels. Do the romance novel and the Future of the Book have anything in common? Of course not! any right-thinking future-bookist would angrily declare. The future, as everybody knows, is the domain of science fiction, not the romance. A look at

“Harlequin” has achieved brand ubiquity: a “harlequin” is a trashy, disposable romance novel, just like a “kleenex” is a tissue and a “xerox” is a copy. We don’t even bother thinking about the word any more than we usually think about romance novels. Do the romance novel and the Future of the Book have anything in common? Of course not! any right-thinking future-bookist would angrily declare. The future, as everybody knows, is the domain of science fiction, not the romance. A look at  There’s also participatory authoring: in the

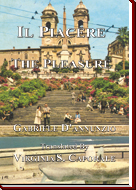

There’s also participatory authoring: in the  I went to Boston over the weekend and grabbed a book at random from my bookshelf for reading on the trip – an English translation of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il Piacere. D’Annunzio is probably best known to English-speaking audiences as being the novelist in residence for the Fascists – which he was – though he’s also the closest thing the Italians have to Proust. I’ve meant to read D’Annunzio for a while out of a vague sense of duty; however, you don’t often see him in English translations, and when I saw this copy for sale in a used book store a few months ago, I picked it up. Little did I suspect that it would provide fodder for rumination about the present and future of the book and publishing.

I went to Boston over the weekend and grabbed a book at random from my bookshelf for reading on the trip – an English translation of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il Piacere. D’Annunzio is probably best known to English-speaking audiences as being the novelist in residence for the Fascists – which he was – though he’s also the closest thing the Italians have to Proust. I’ve meant to read D’Annunzio for a while out of a vague sense of duty; however, you don’t often see him in English translations, and when I saw this copy for sale in a used book store a few months ago, I picked it up. Little did I suspect that it would provide fodder for rumination about the present and future of the book and publishing.